AARP Hearing Center

The dog is old.

Age snuck up on him. Maybe this will happen to me, too, if I'm lucky. Maybe it already has. But what human has the genes and the luck and the sheer savoir faire to disguise the years as well as this amazing specimen of canine charisma does?

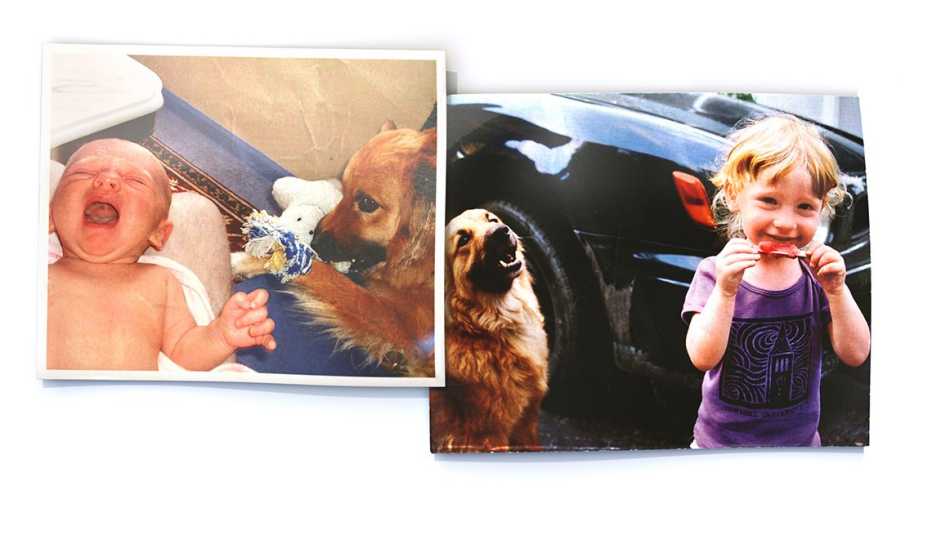

His teeth are bright. His muzzle, black; his coat, feathery. He can bounce a soccer ball off his nose. On the street, everyone loves him. "Your dog is so pretty! How old is he?" they often ask. They're astonished to hear the number. He's 10. He's 12. He's 14. On it goes, year upon year. He's ageless; he's immortal.

But look closer. When he runs, his gait is stiff. In the depths of his irises, clouds are gathering — cataracts, says an eye doctor pal. "He's old," I tell everyone who asks. "He's an old man." I pat his head. "Aren't you? Who's an old man?"

The dog gazes up. Me?

"Dog years" are fluid things; smaller breeds live longer than big ones, and none seem to really get older and wiser, like we are supposed to do. Emotionally, a domestic dog exists in a kind of perpetual adolescence, a long summer twilight of play and napping and happy routine in the company of parents who never get old, and never let you grow up.

The scientific term for this Peter Pan state is "neoteny" — when adults retain juvenile traits — and it's one of many characteristics of older canines to invite inquiry from longevity researchers. Daniel Promislow, who studies aging at the University of Washington, recently assembled scientists from various disciplines to join a Canine Longevity Consortium. Armed with a grant from the National Institute on Aging, they're laying the groundwork for the first national longitudinal study on aging in dogs.

Why? The researchers are exploring an audacious idea: Dogs are in many ways our mirror species. "Unlike most [animal] models used to study aging, dogs aren't in a lab — they share the same environment we do," Promislow says. Domestic dogs exhibit huge genetic variability, eat processed food, sleep in our homes (hell, right on our beds) and enjoy access to humanlike health care.

Increasingly, they also get sick and die like us: They acquire arthritis and heart disease and many of the same cancers; they grow frail and forgetful. Often their lives are extended by expensive medical interventions. What Promislow and his colleagues hope to do is discover what factors allow some dogs to better fend off these indignities. One proposal: giving older dogs low doses of a drug called rapamycin, which has been effective in extending the lives of mice by up to 13 percent. The hope is that what works for them will work for us.

Sleep better and weigh less

We don't know exactly how old the dog is. Rescued by a friend in the mid-1990s, this dog arrived a stray, skinny and wary but full grown. He was what sociologists would now call an emerging adult. This worked out, since I was one, too.

More on Health

How 2 Minutes of Exercise Can Help You Live Longer

Research shows how much — and which types — you really need