It was not to be. After six hours in the police station, an FBI agent finally did what someone should have done when I arrived: He asked who I was. He was not amused to discover I was a reporter. He told me to leave immediately, seemed in a mood to kill me and said something to that effect.

I never got that scoop. But I had gotten the first interview with Oswald's mother, my story was picked up by both Time and Newsweek, and for the next two days I covered the awful story that left the nation in shock and altered America forever.

When everything changed

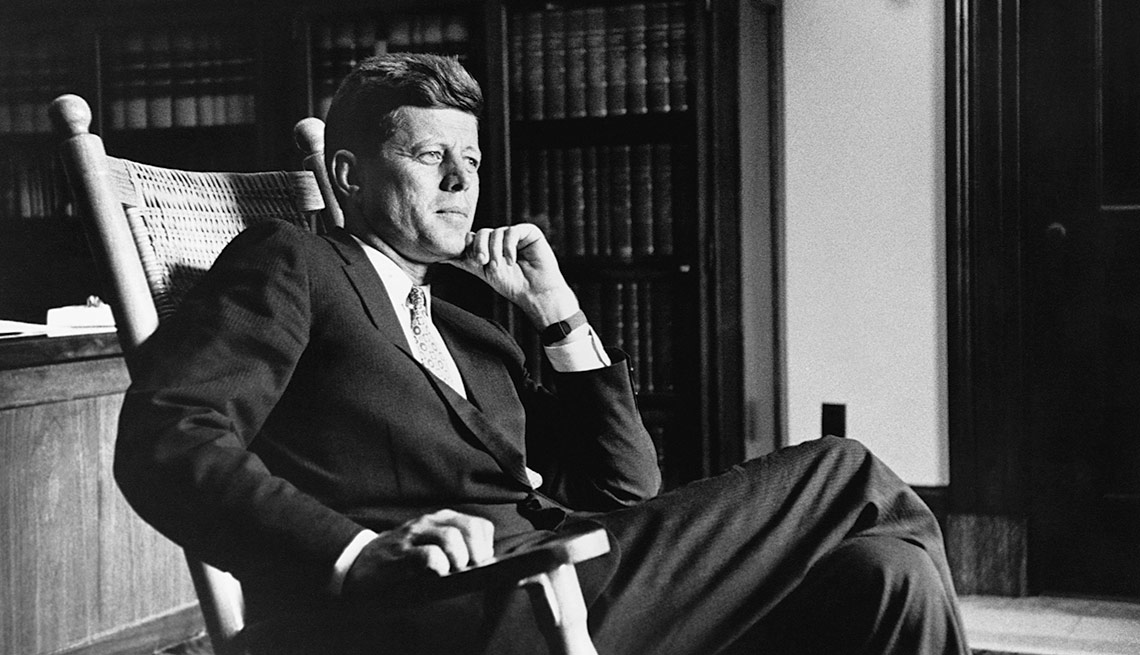

That weekend would be a turning point for the nation in so many ways. We had always thought of our presidents and the presidency itself as larger than life; our presidents were all but invincible. And suddenly this young president, in the prime of his life, was shot down by a madman. He was as vulnerable as the rest of us.

We had never gone through anything like this. We didn't know what it meant, beyond just the tragedy of a president being murdered. When it first happened, the government closed off the borders with Mexico. We didn't know if this was some kind of conspiracy or even the first shot of World War III. There was a great feeling of terror that hung over people. Your first emotion was, "Why did this happen?" "Who did it?" and "Why?"

There had been considerable right-wing hostility toward Kennedy in Dallas before the president arrived, with hateful signs and some nasty advertisements. But most people didn't feel that way. Kennedy got an overwhelmingly friendly reception in Dallas. The night before, he was cheered when his plane arrived at Carswell Air Force Base in Fort Worth. More than 10,000 people showed up at 11 o'clock at night.

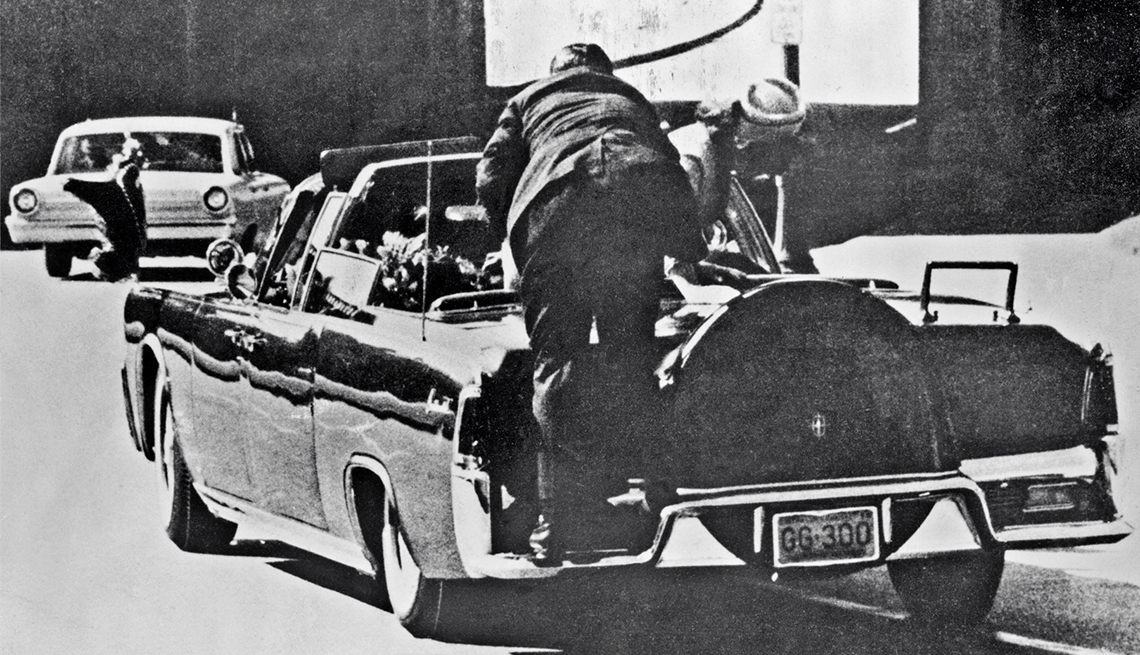

When the president arrived at his hotel, he and Mrs. Kennedy discovered that local citizens had hung a priceless collection of paintings on the walls of their suite. The Kennedys appeared at a breakfast that morning, and Fort Worth's A-list gave him another warm welcome. He was also cheered when he spoke outside the hotel. As the president's motorcade approached downtown Dallas, Nellie Connally (wife of Texas Gov. John Connally), who was in the president's car, said to Mrs. Kennedy, "You can't say Dallas doesn't love you." And then they turned the corner, and this guy shot him.

It turned out that Oswald was anything but from the right wing. He had defected to the Soviet Union at one point and later led pro-Castro demonstrations. Nobody knew what to make of it. Being a police reporter, I wasn't nearly as interested in the ideology or motivation that might have been behind the assassination; I just wanted to find out who did it. It soon became clear to me that Oswald was a cold-blooded killer. Before they arrested him, he had shot Dallas policeman J.D. Tippit at point-blank range. He was a person without a conscience. To this day, nobody has shown me evidence and convinced me that there was somebody else involved.

But there could have been. I've always had an open mind. I think it will always be a mystery — one of those things that we may never know the answer to. It was such an overwhelming story, and such an overwhelming tragedy; I'm not convinced people will ever be satisfied that Oswald acted alone. But there are still questions about the details of Lincoln's assassination. For that matter, there are still questions about the assassination of Julius Caesar.

The president's brother U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy comforts his children after hearing about JFK's death.

Bettmann/Corbis

A media moment

The Kennedy assassination was also a dramatic turning point for journalism. For the first time in the history of the country, the entire nation focused on one story and watched it unfold live on television.

Up until that weekend, the majority of Americans got their news from print. From that weekend on, television became the place where most Americans got their news.

This was an era of gatekeeper journalists. You had Walter Cronkite. You had Chet Huntley and David Brinkley. You had the editors of the New York Times and other powerful mainstream newspapers. In a sense, we were all getting information and basing our opinions on the same stuff.

Now our news comes from a variety of places. We're into this era of what I call validation journalism, where people watch a certain channel or listen to a certain show because they are looking not necessarily for facts but for a news product that validates what they already believe. You can get your news from a liberal point of view, or you can get it from a conservative point of view. The real problem is: Is it true? Can it be trusted? You have to be very discerning.

More From AARP

10 Events That Shaped Hispanic America in 1973

A snapshot from 50 years ago highlights political, art and entertainment moments in the lives of U.S. LatinosStories From People Who Became Witnesses to History

From JFK to the death of a princess, these ordinary people lived through extraordinary events

7 Leaders Who Carry on Martin Luther King Jr.'s Legacy

These modern trailblazers continue to work on civil rights issues