Tribute to Veterans: Readers Share War Letters

AARP members submit nearly 10,000 pieces of correspondence from family members

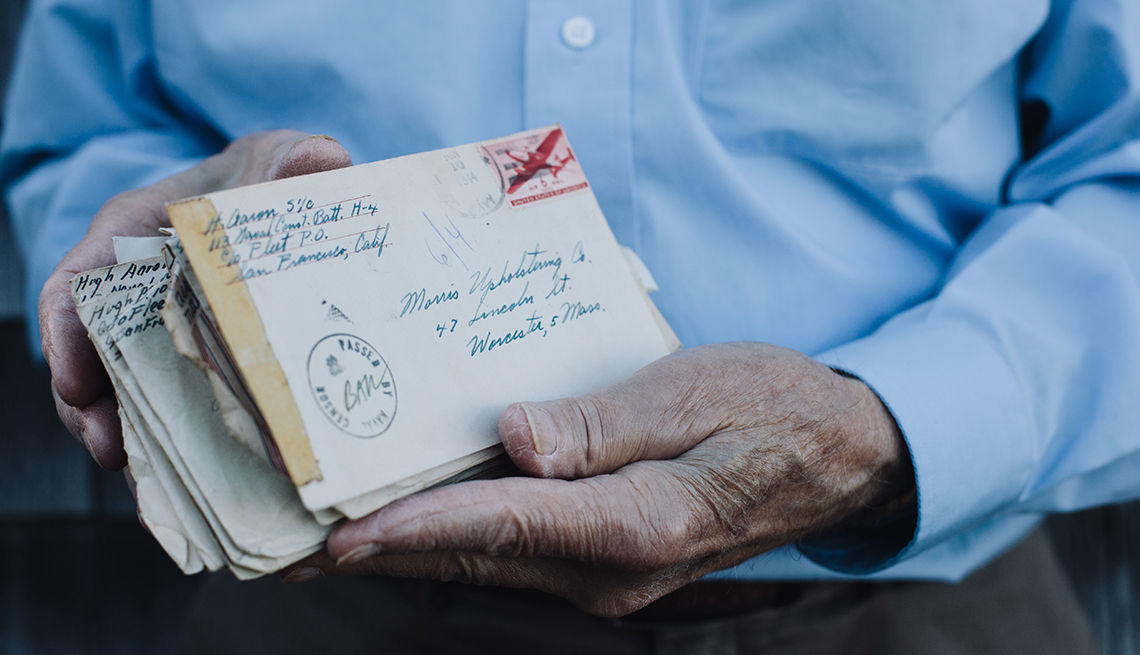

Tristan Spinski/Grain

Readers share their "war letters" from family members who wrote to them on duty.

When the Bulletin asked historian Andrew Carroll to write its May cover story, "Last Letters Home," we hoped to honor Memorial Day and touch the hearts of readers with tales of sacrifice by American service members.

But no one anticipated just how moved our readers would be, or how many would be motivated to share some of their own history.

Within days, Carroll, who began gathering letters from service members in 1998 as part of a project that eventually spawned a best-selling book called War Letters, started hearing from Bulletin readers who sent along letters from their loved ones. What began as a trickle grew swiftly into a flood. "I'm still reading through the incoming mail," Carroll said. "But I think the overall number of new war letters submitted by AARP members is nearing 10,000."

The letters sent in by Bulletin readers document remarkable deeds from the U.S. Civil War to Iraq and Afghanistan. Some of the letters are notable for how they were written as much as for what they said — like one composed on toilet paper by a soldier fighting in Vietnam. "I've been collecting letters for 16 years now," Carroll said, "and I've never seen anything like that before."

The readers' letters, which will be preserved at the Center for American War Letters at Chapman University in California, include some with historical significance.

Secrets revealed

One, written on May 2, 1865, by a man named Garret Clawson, captured the moment when Union troops learned that the Civil War was over. "The news came here this morning that the rebs had agreed to the terms and peace was made," he wrote. "The rebel soldiers is acoming through here ever day on thare way home. They say that war is ended and they are glad of it. The rebs soldiers and our soldiers is a walking and talking and cutting up together as if they had always been friends."

Other seemingly mundane letters yielded striking secrets.

"I am in Iceland," Stewart Evans wrote to his mother on Sept. 24, 1941, from aboard the USS Reuben James. "[W]e have been in and out of here for six days now and I do not know when we are leaving. … I can't think of anything to write," he continued. "I am well and not working hard. … If things turn out as they have planned for this craft I will spend Christmas at home and I certainly hope they do."

That was not to be. On Halloween, 1941, the Reuben James was torpedoed by a German submarine while escorting merchant convoys headed to Great Britain. Of the ship's 160 crewmen, 115 were killed, including Evans. While most Americans consider Pearl Harbor to have been the opening attack on our armed forces in World War II, Evans and his shipmates died more than five weeks earlier.

Andy Carroll

World War II soldier Genevieve "Gene" Sobolewski sent a letter to her fiancé, and it was returned to her with the word "deceased" on the envelope.

Letters to a fiancé and to a mother

Letters arrived from Bulletin readers that preserve the thoughts of women as well as men, and from the descendants of service members of all races and social positions.

Amy Quinn, the daughter of a Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) soldier named Genevieve "Gene" Sobolewski, sent in a box full of her mother's correspondence from World War II. Many of the letters were to her fiancé, John Russell Harshbarger, who was fighting in North Africa. On Oct. 30, 1942, Sobolewski wrote a letter expressing how much she loved him and telling him to expect a Christmas gift in the mail. But Harshbarger was killed in action before he received the letter, and it was sent back to Sobolewski with the word "deceased" written in red on the envelope.

Among the most tragic letters were those that marked the last messages from soldiers killed in war.

"Since I last wrote to you, I was assigned to Co. 'D' of the 31st Inf. Regt. in 'Korea,' " an African American private named Bromley Berkeley wrote to his mother on Oct. 5, 1952, at a time when Army units in combat were first being integrated. "We were on the 'Front Lines' for about 5 days when I got into the company. I am in the 'Machine Gun' Section." Berkeley went on to ask his mom to send candy. "The reason I want candy is because it is getting cold & candy helps to keep you warm. Secondly, when we are on the 'Front Lines' you get Good Food, but not enough. … Well no more to say right now, so until I hear from you again please write soon and tell everybody 'hello' for me. Yours Truly, Bromley." Berkeley was killed just over a week later in the Battle of Triangle Hill.

Most of the letters were contributed either by the troops and veterans who wrote them or by their families. Others came from those with no family ties to the writers, but a strong urge to see history preserved. One reader from New York sent in a bundle of World War I letters purchased at a yard sale. A reader in Charlottesville, Va., came across dozens of original World War II letters in a stamp collection.

Letters were donated by readers from Hawaii to the Virgin Islands and nearly every state in between.

Last letters home

The rarest type of letters collected by Carroll are those from soldiers who know they are about to die. Some were dictated from hospital beds or dashed off in haste by combatants who had been severely wounded and doubted they would survive.

But one letter received by Carroll after the Bulletin article appeared depicted an even more rare moment — a Confederate soldier facing execution in the Civil War.

The letter was written by a Kentucky man named Lindsey Buckner, who was selected to be shot in retaliation for the death of a Union soldier killed by Confederate guerrillas in his home state. "My dear sister," Buckner wrote in late October 1864, "I am under sentence of death and for what, I do not know. … It is a hard thing to be chained and shot in this way; and if it was not for the hope I have of meeting you all in Heaven, I would be miserable indeed."

A dad writes his girls

While some of the letters documented long-ago wars, others felt as immediate as yesterday, and as poignant as recent headlines.

After receiving word that he would be deployed to Iraq, U.S. Army Capt. Zoltan Krompecher sat down and composed the following letter to his two young daughters. "Dear Leah and Annie," Krompecher began:

U.S. Army Capt. Zoltan Krompecher wrote his “precious little girls” before leaving for Iraq. From left, Annie, wife Tina, Leah and Jack.

My precious little girls. I write this letter to you because soon I will leave for Iraq. Your mommy and I just tucked you both into bed, read your books, and said our prayers together.

I've been watching the news and am worried that there could be the off-chance that I might never get to watch you board the school bus for the first time, place a Band Aid on a scraped knee, or walk you down the aisle of your wedding. …

One night during this past December, I read you girls The Snowy Day before bedtime. The next morning revealed three inches of fresh powder. That morning you greeted me with the plea, "Daddy, can we go outside and play like Peter did in his book?" Sadly, I replied that I had to get to work but maybe we could build a snowman after I returned home. Unfortunately, it was so dark by the time I got back from work that there was no time for snowmen.

April has arrived, and I have put the sled away until next year. Winter is over, and I leave for Iraq next month. ... All I can hope for is that it will snow just one more time.

Love, Your Daddy.

Unlike so many stories Carroll has read in letters over the years, this one had a happy ending. Krompecher returned to his family and donated his letters to Carroll after reading of his project in the Bulletin. "Zoltan's letter is proof that troops today are writing letters as eloquent and profound as those that were penned decades and even centuries ago," Carroll said.

Also of Interest

- 20 movies, books and shows that totally flopped

- Want to lose weight quickly? Try these tactics

- Help bring relief to struggling seniors; find volunteer opportunities near you

Visit the AARP home page every day for more politics and news