AARP Hearing Center

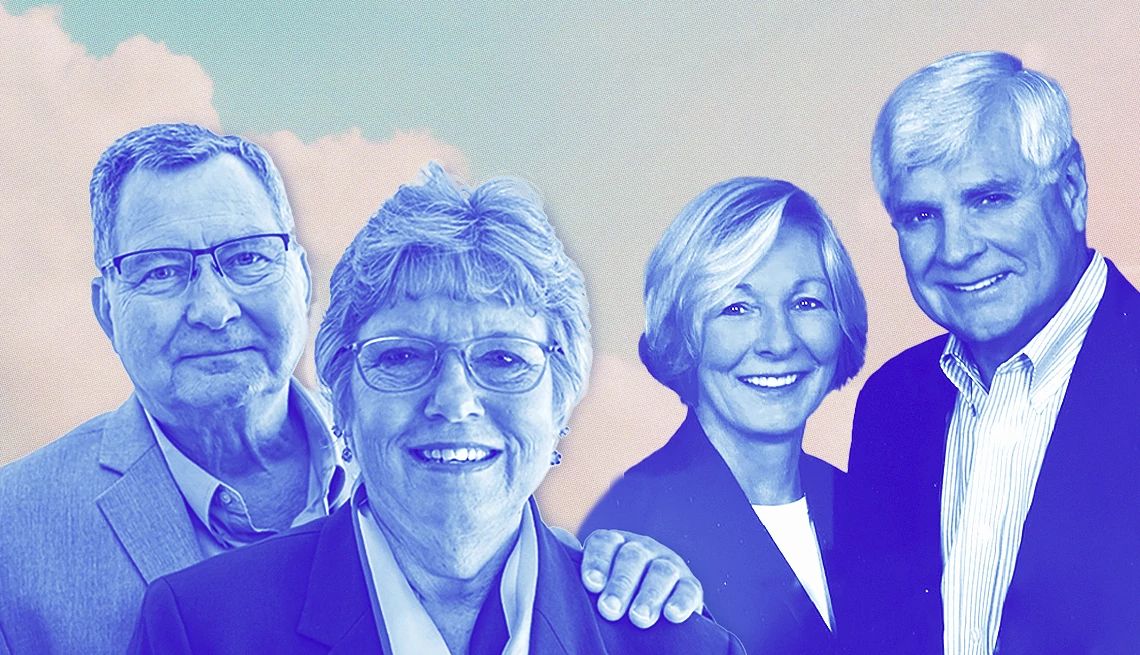

COPD — chronic obstructive pulmonary disease — “is a tough disease,” says Colleen Brennan-Martinez, 64, a retired nurse practitioner from New York City whose father, James Brennan, died from COPD in 2020 at age 84. It’s tough for those who have it and struggle to breathe, she says, and it’s tough for those who watch them struggle.

Seeing a loved one gasping for air can be “very frightening,” says Goldia Brown, a 60-year-old funding analyst from Fairburn, Georgia, whose mother, Goldia Cotten Brown, died of COPD in 1997 at age 52. As a volunteer for the COPD Foundation, an education and advocacy group, she often talks with families about those fears.

But these veteran caregivers, along with medical professionals who treat COPD, say caregivers should know that COPD is more treatable than many people realize — and that they can help their loved ones live better, longer lives.

“There are so many things that can be done,” Brown says. “I would want them to know that there is hope.”

Here’s what experts say caregivers for people with COPD should know.

What is COPD?

COPD is an umbrella term for a group of diseases that block airflow in the lungs, making it hard to breathe. The major types are:

- Emphysema. With emphysema, small air sacs (alveoli) inside the lungs are damaged. Because of the damage, the walls between sacs break down, creating larger sacs that don’t work as well. It gets harder to breathe air out.

- Chronic bronchitis. This is when the bronchial tubes that carry air to and from the lungs are constantly inflamed, producing mucus. If you cough up mucus most days for at least three months over two years, you could have this form of COPD.

“You can have all these manifestations in an individual patient,” or just some of them, says Fernando Martinez, M.D., chief of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York (and Brennan-Martinez’s husband). While people are commonly diagnosed with COPD in their 60s or 70s, symptoms often start earlier, he says. In addition to shortness of breath and coughing, symptoms can include wheezing, chest tightness and tiredness.

The primary test for COPD is called spirometry. In this test, you blow through a tube into a machine called spirometer. It measures how forcefully and completely you can get air out of your lungs. The same test can be used over the course of the disease to see how it’s progressing.

What causes COPD?

In the U.S., the major cause of COPD is smoking, though “up to probably 25 percent of COPD occurs in people who’ve never smoked,” says David Mannino, M.D., chief medical officer and cofounder of the COPD Foundation. Other causes include dust, fumes and chemicals in workplaces, as well as secondhand smoke. Some people have a genetic condition, called alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, that causes COPD. (It’s diagnosed with a blood test.)

The link with smoking is a source of shame and blame for some families, says Keith Siegel, a respiratory therapist in Union, Maine. “It’s really important for caregivers to understand that it doesn’t matter why they have this disease,” he says. “They have this disease, and they need help and they need support.”

That support, he adds, should include helping loved ones try to quit smoking — even if they’ve tried many times before.

More From AARP

How Cold Weather Affects the Lungs

Frigid, dry air can make it harder to breathe

Dementia Caregiver's Guide: Tips for Unique Challenges

The latest research on dementia, plus tips to keep your loved ones safe and happy

AARP Smart Guide to Seasonal Allergies

Achoo! How to understand and treat your symptoms