New Medicare $35 Insulin Benefit Will Cut Costs for Millions

Beneficiaries have all of 2023 to switch plans for a lower price on that diabetes treatment

For William Koopman, learning about the new law that caps insulin copays in his Medicare prescription drug plan at $35 a month was an incredible relief. For the first time since he enrolled in the program, the 70-year-old will be able to use the insulin his doctor prefers and for a price he can afford.

“I’m very thankful for this,” Koopman, a retired railroad supervisor from Hometown, Ill., told AARP. “It’ll be less than half the cost.” Koopman takes two different insulins each day for his Type 2 diabetes, and is one of about 1.4 million Medicare enrollees that federal officials say can benefit from the provision in the 2022 budget law that beginning in January limits copays for insulins that Medicare covers at $35 a month. Some Medicare enrollees with diabetes take their insulin through a pump. The $35 maximum copay for insulin for that delivery system will begin on July 1, 2023.

Koopman found out about the new benefit from Dave Lecik, a State Health Insurance Program (SHIP) specialist in Illinois who has been training counselors and advising Medicare beneficiaries for 11 years on how to find Medicare plans that best meet their needs. “It’s a great thing they’ve done to pass this law,” Lecik told AARP.

More time to get the best plan

Taking advantage of this new benefit can be a little tricky. The law that created the monthly copay cap was signed in August 2022, after the premiums and copays for 2023 were already set and loaded on the Medicare Plan Finder, the website that helps Medicare beneficiaries compare and choose Part D prescription drug plans and Medicare Advantage plans, the private insurance alternative to original Medicare. Most Advantage plans also cover prescription drugs. Medicare officials say that the Plan Finder cannot be updated with the $35 copay cap information until 2024.

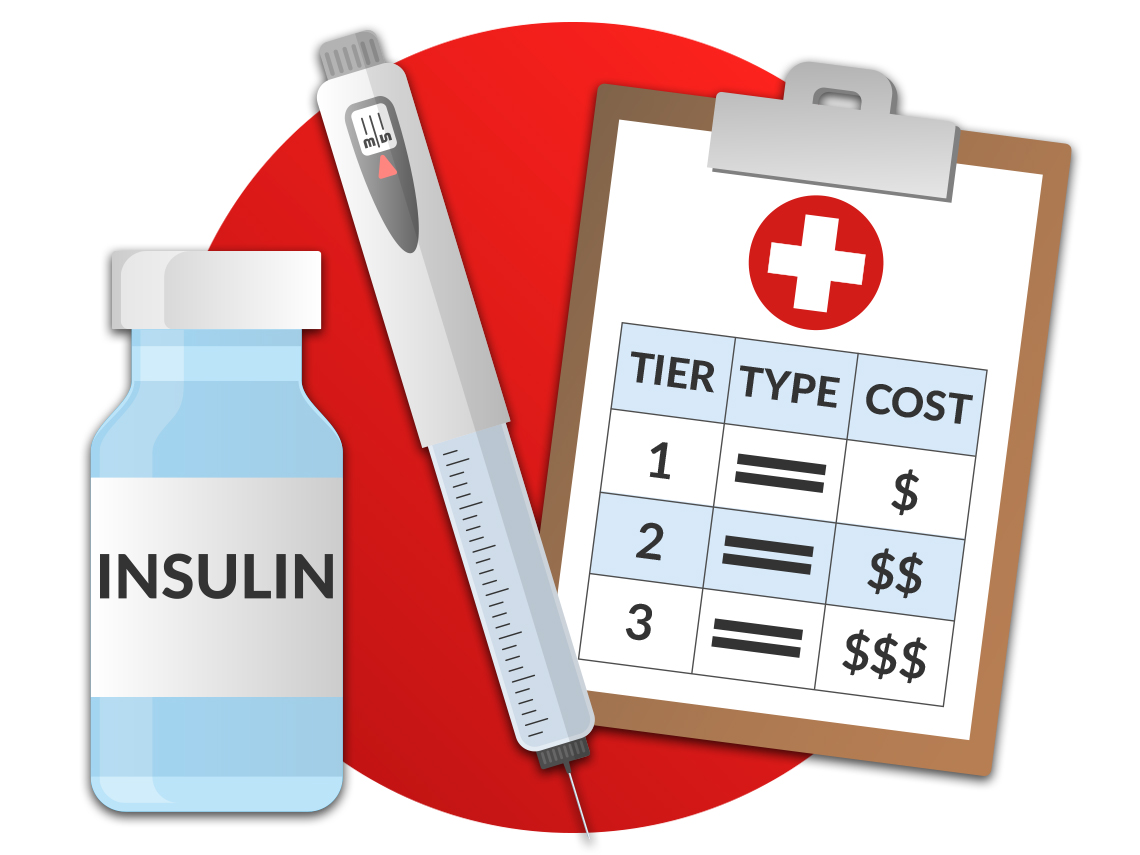

The Plan Finder can be tough to navigate. There are more than 70 insulin products on the market and not every plan covers them all. And, many people with diabetes also take other drugs. Consumers need to factor in the cost of all their medications — as well as any monthly premium plan charges — when picking a drug plan that covers their particular type of insulin. And there are a lot of plans to sift through and compare. Not having information that includes the insulin copay cap poses a challenge for many, including plan counselors like Lecik.

Because the Plan Finder doesn’t include the $35 copay cap, which has led to some confusion, CMS created a Special Enrollment Period that will give beneficiaries who use insulin until the end of 2023 to switch plans if they didn’t get the best deal during last year’s open enrollment. This will also give Medicare enrollees with diabetes who did not review their coverage a chance to take a look and see if they can save money with a different drug plan. According to a study from the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation, in 2020 fewer than a third of beneficiaries even checked to see if they could get a better plan during that year’s open enrollment. Only 1 in 10 original Medicare beneficiaries actually switched plans that year.

CMS is advising enrollees to consult either the Medicare hotline (1-800-633-4227) or SHIP counselors like Lecik to help them navigate the Plan Finder and select a plan that best meets their needs. There are SHIP offices in every state, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and U.S. territories.

Insulin costs were out of reach

Lecik had started advising Koopman in 2022 and discovered then that the brand-name insulins his doctor prescribed would cost him more than $1,000 a month out-of-pocket. Then they looked at generic versions of the medicine, but the best deal for those products still would have cost Koopman $723 each month.

“I couldn’t afford that,” he says. When Koopman explained his situation to his doctor, she suggested he go outside his Part D plan and shop around. Koopman was able to find generic versions of the two insulins at $144 a month for both medicines. But there was a catch: He was forced to use vials and syringes to take his daily doses instead of the simpler prefilled insulin pens. And, Koopman says, he was taking a “lower grade” of insulin, so he needed to take more each day. Even then, he says the insulins he could afford didn’t control his diabetes as well as the type he took when he had employer-based health insurance.

AARP Membership -Join AARP for just $12 for your first year when you enroll in automatic renewal

Join today and save 25% off the standard annual rate. Get instant access to discounts, programs, services, and the information you need to benefit every area of your life.

With the new $35 benefit, Lecik found a Part D plan for Koopman that covers all his medications, will allow him to use the insulin his doctor prefers, and he’ll only have to pay $70 a month for both drugs compared to the $144 he has been paying for generics and the more than $1,000 he would have had to pay for the brand-name products.

“I’m going to go to my sugar doctor in two weeks and ask her to write out scripts for the old stuff,” Koopman says, adding that he won’t quite believe this benefit is true until he goes to the pharmacy and gets the prescriptions filled.

Refunds available for overpayment

According to CMS, insurers have until the end of March 2023 to make sure that Medicare beneficiaries are not charged any more than $35 a month for an insulin their plans cover. If a plan has charged someone more than $35 a month for covered insulin in 2023, the insurer has 30 days to refund a Medicare enrollee the amount they were charged over $35. CMS officials say beneficiaries should contact their plan to find out how to get reimbursed.

Dena Bunis covers Medicare, health care, health policy and Congress. She also writes the Medicare Made Easy column for the AARP Bulletin. An award-winning journalist, Bunis spent decades working for metropolitan daily newspapers, including as Washington bureau chief for the Orange County Register and as a health policy and workplace writer for Newsday.