AARP Hearing Center

Chapter One

London, Spring 2022

John Betjeman was right. Nothing bad could ever happen at Peter Jones. Thus thought Archie Williamson as he sipped his cappuccino and looked out over London’s rooftops from the Sloane Square department store’s sixth floor café. The café was Archie’s happy place. Even on a grey day the atmosphere was sunny as people took turns at the window tables, understanding that one did not linger for hours over a single latte in front of this fabulous view. Archie nodded with satisfaction as a young woman with a laptop ceded her place to a frazzled mother with two small children, saving him from having to do the same.

LIMITED TIME OFFER: Labor Day Sale!

Join AARP for just $9 per year with a 5-year membership and get a FREE Gift!

With his own lunch companions still en route, Archie shook out the copy of the previous evening’s Standard left behind by his table’s last occupant and turned to the puzzle pages. Codeword was his favourite. He was getting faster each time, though it would be a while before he was able to crack the puzzle as quickly as his great-aunt Penny could.

As he pondered whether the number twenty-four represented an “a” or an “o,” Archie’s phone buzzed with a message. It was Arlene, Penny’s housekeeper, letting him know that she’d put Penny and her older sister Josephine into a taxi which should reach Sloane Square at any moment. Archie thanked Arlene for letting him know. She really was a treasure. But after forty minutes more there was still no sign of Archie’s beloved great-aunts. Then, just as he was about to call Arlene and ask her to check the taxi’s progress on her app, a managerial-type with a Peter Jones partner’s badge came flying up the escalator, calling out as she went, “Mr. Archie Williamson? Is there a Mr. Archie Williamson in the café?”

“Right here,” said Archie, standing up and giving her a wave. Two customers seated on the first inner row of tables stood up at the same time, ready to take Archie’s place by the window the very second it was vacated. They eyed each other like Olympic athletes at the start of the hundred metres and would move just as quickly the moment Archie stepped out of the way.

“Thank goodness,” said the woman, whose name, according to her badge, was Erica. “It’s your great-aunts. The Misses Williamson? I need you to come with me.”

Archie was immediately worried. “Are they OK? Are they hurt?”

There had been an incident the previous month when Josephine slipped on a discarded burger outside McDonald’s on the King’s Road and took Penny down with her as she fell. They’d both had to spend the night in the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital with suspected concussion.

“No, no,” said Erica. “They’re both fine. At least physically they are.” She dropped her voice. “It’s something else. Something … Mr. Williamson, I think it might be easier to discuss this somewhere private. Would you mind?”

Archie followed Erica back down the escalator. When they reached the ground floor, Erica led Archie through the shelves of neatly-stacked towels and bed linens to a door he hadn’t previously noticed. She pushed the door open so that Archie could go ahead of her.

“Your great-aunts are in here,” she said.

Archie found it difficult, letting Erica hold the door for him when manners dictated it should have been the other way round, but he nodded and stepped inside all the same. He still didn’t know what to expect.

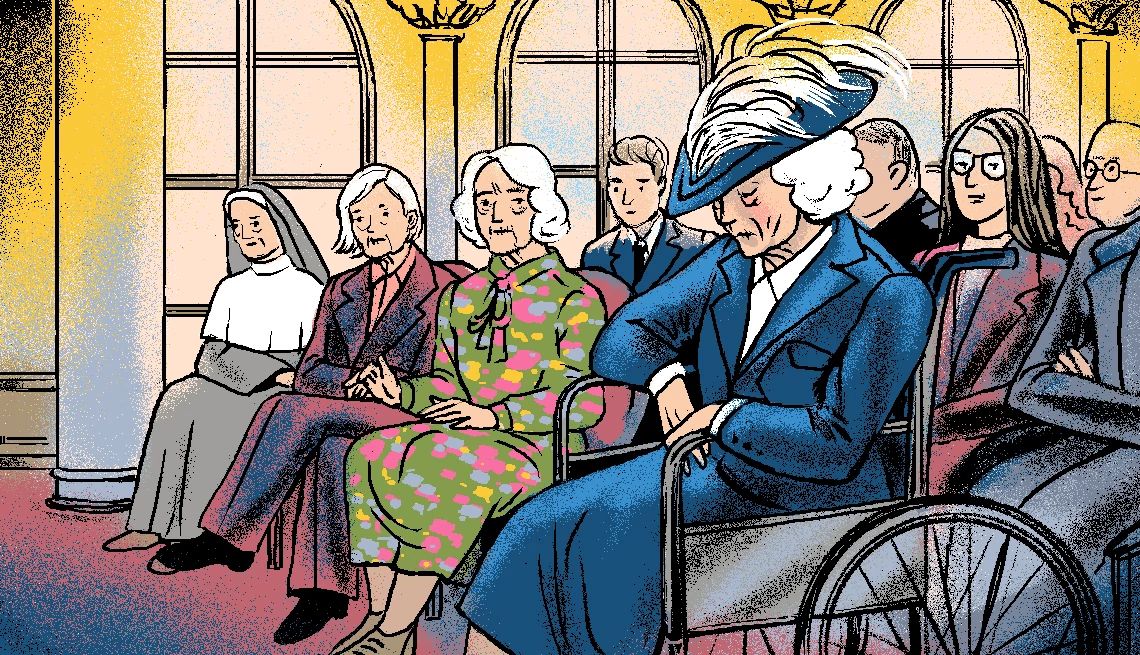

In a plain room decorated with tasteful pastel prints (available for sale on floor four), Archie’s great-aunts sat side by side on two chairs opposite a very tidy desk. Though it was a balmy spring day outside, they were both well-muffled in coats and scarves. Josephine was wearing a blue fisherman’s cap; Penny, her favourite mohair beret. Archie was always surprised by how small his aunts looked when he saw them out of the context of their South Kensington home but this time they looked tinier than ever. Perhaps it was the contrast with the two enormous men flanking them like sentries. Plain-clothed security officers, Archie realised with growing concern.

“Oh, Archie. Thank goodness you’re here,” said Josephine. “There’s been a terrible misunderstanding.”

“What’s going on?” he asked.

Auntie Penny looked down at her size three-and-a-half feet in their neat Velcro-fastened shoes. When she looked up again, her face wore the expression Archie recognised from every photograph of his younger great-aunt taken between 1924 and the beginning of World War Two. She’d been up to something. What on earth was this “misunderstanding” about?

“Archie, dearest, I’m so sorry to embarrass you like this,” Penny began. “I only picked it up to have a look but I must have let myself get distracted and before I knew what I was doing I had put it in my handbag and closed the zip quite without thinking.”

The “it” in question was a small Swarovski-style crystal elephant, now standing on its hind legs in the middle of Erica’s desk.

“Are we calling the police?” asked one of the security guards.

Lovely Erica chewed her lip. She looked from the guard to the sisters to Archie and then back to the guard again. Her discomfort was palpable.

“I don’t think calling the police will be necessary,” Archie interjected quickly. “As you can see, my auntie Penny is …”

How to not say “ancient” in front of her?

“Well, I’m sure she won’t mind me saying that there are occasions when she becomes a little forgetful, but she does not have a dishonest bone in her body and she would never have sought to deprive Peter Jones of its property by stealth. She’s as honest as the day is long. It’s just … it’s just, she has … you know … she’s got …”

No. He couldn’t say the “d” word either, even if it might help keep Penny out of jail.

“It’s just that she’s recently turned ninety-seven.”

Penny nodded wretchedly, suddenly looking every one of her years.

“I was in The War,” she said.

“So was I,” said Josephine.

“In fact,” Archie continued. “I came here today to meet my great-aunts in the café to discuss their taking part in the VE Day celebrations at the Royal Albert Hall. VE Day? To mark the anniversary of the end of World War Two?”

“In Europe,” Penny qualified. “The War didn’t end in the Far East until much later the same year.”

“That’s absolutely right, Auntie Penny.” Archie turned back to Erica. “They’re going to be meeting Prince Charles in their capacity as representatives of the women’s services.”

The security officer who wanted to call the police seemed unmoved but Archie could see that the younger man and Erica at least were impressed to hear they were in the presence of real live World War Two veterans.

“I was in the Wrens,” said Josephine.

“Women’s Royal Naval Service,” said Archie.

“And I was a FANY,” said Penny.

“First Aid Nursing Yeomanry,” Archie quickly explained.

“Thank you for your service,” said the younger guard.

It was a platitude that Archie knew both his aunts hated but that day they had the grace (or the sense) to simply thank the young man for his kindness.

“I’d be very happy to pay for the elephant,” said Archie, in an attempt to bring the situation to a conclusion. “Perhaps then we can put all this behind us and let you get on with your day.”

“Store policy … ” the older officer began.

“Is that every incident like this has to be processed in the official way,” Erica jumped in. “I know, John, I know. But perhaps in this case since, technically, Mizz Williamson hadn’t exited the store ... ”

Archie smiled gratefully and handed over a credit card. “For the elephant.”

“You don’t have to,” said Erica.

“But I’d like to,” said Archie.

He reasoned that Penny must have wanted it.

“Well, if you really want to. We ’ll have to take it to one of the tills.”

“Are we not calling the police then?” asked John.

“We ’re not calling the police,” Erica confirmed. “Not today. Ladies?”

She opened the door to let Penny and Josephine back out onto the shop floor.

Archie parked Penny and Josephine in the cushion aisle while he paid for the hideous crystal knick-knack. It was astonishingly expensive. Excruciatingly so for something so very, very ugly. Who on earth bought these things out of choice? Who would ever bother to steal one?

“I think we’ll have lunch at Colbert today,” Archie told the sisters when he rejoined them. He felt the need to be outside and well away from the scene of the crime. The two security officers had headed in the direction of the main doors which opened straight onto Sloane Square, so Archie ushered his great-aunts out via the scented candle department onto Symons Street instead, making it clear by his body language that this was no time to stop and sniff the Cire Trudon Abd El Kader candle that reminded Penny of her time in Algiers.

Chapter Two

Archie Williamson’s earliest memory of his great-aunts was of an afternoon in the Highlands in the summer of 1987 when he was six and a half years old. Archie’s parents had taken him to Scotland to see Grey Towers, the Williamson family’s ancestral home (now in the care of the National Trust for Scotland), and Josephine and Penny were staying nearby in all that remained of the once vast family estate: a small bothy without running water or electricity. The sisters were on a fly-fishing holiday. They’d arrived at the self-catering cottage where Archie and his parents were staying, laden with freshly-caught trout and bickering over who had hooked the biggest.

“These are your grandfather’s sisters,” said Archie’s father Charles.

Archie was immediately fascinated by the two women, who were far older than anyone he had ever met before, though they could only have been in their sixties at the time. Still, sixty is ancient when you’re not even seven. They were from another era—might as well have been from another planet—yet somehow by the end of the afternoon, Archie felt a kinship with Penny and Josephine despite the many decades between them. Perhaps it was the way they spoke to him. From the very beginning they treated him like a small adult, expressing great interest in his preferences and opinions. When they offered to teach him how to fish, he was delighted. The following day, the sisters took Archie to the loch for their first big adventure as a trio. Though Archie’s parents worried that their sweet and bookish only child might not enjoy a day’s fishing with two sexagenarians, Archie loved it. He only grew more captivated by his newly-met relations; these exotic creatures who rowed like sailors and swore like builders, yet could keep their hairdos perfect all day long. By the time they brought him back to his parents, Archie had a good grounding in fly-fishing and a greatly expanded vocabulary of swear words. He couldn’t wait to see the sisters again.

WHEREVER THERE WAS an opportunity, Archie went to stay with his great- aunts and they were thrilled to have him. On further Scottish holidays in the bone-chillingly cold bothy—which his father had accurately described as, “like camping, only worse”—the sisters gave Archie an alternative education. They taught him how to identify the local flora and fauna. They taught him how to catch his supper. They taught him how to lay a fire. It was all so much more exciting than the late twentieth-century childhood he was enduring back in Cheltenham. At home, he wasn’t allowed to touch the matches. With Penny and Josephine, he was allowed to throw cap-gun pellets onto a raging bonfire.

“They’re a terrible influence,” Archie’s mother complained, when he came home from that trip with singed eyebrows.

Certainly the sisters always gave him the most age-inappropriate gifts. Among Archie’s favourites was a set of books he received for his tenth birthday. While his godmother worried that she might have overstepped the mark when she sent him something from the Goosebumps series, Archie much preferred the antique copies of Major W.E. Fairbairn’s All-In Fighting and Get Tough!—manuals on lethal unarmed combat—that Auntie Penny sent from her personal library. He spent that whole summer learning the tricks of Defendu, Major Fairbairn’s trademark “ungentlemanly” martial art, unfortunately managing to break his own wrist in the process. Nevertheless, when he got back to school, the rumour that Archie Williamson had broken his wrist single-handedly defending his household from a burglar, à la Kevin in Home Alone, briefly made him rather popular.

Penny and Josephine introduced him to more refined activities too. At the big white house the sisters shared in South Kensington, Archie learned how to cook cordon bleu and dance the foxtrot. He accompanied the sisters to London’s museums and theatres and listened in awe as they talked in French, German, Italian, and Hausa to the eclectic guests who thronged the house on Saturday evenings to eat, drink, and play cards, while a teenage Archie mixed martinis.

“A little heavier on the vermouth, dear.”

The sisters were mad for vermouth. And gin. They liked their martinis stronger than Molotov cocktails.

As Archie got older, the sisters took him with them on trips abroad; first to Europe, then further afield.

“Always pack a party dress!” was their sage advice for travelling.

Thanks to their careers and family connections—Josephine was an academic whose diplomat husband’s job had taken them all over the world, while Penny had been in overseas aid—it seemed that the sisters could turn up in any city in any country and be guaranteed to know someone interesting who would invite them to tea: writers, artists, disgraced ex–government ministers …

When Archie moved to London to take up a job in a gallery, one of the things that excited him most about living in the capital was that he would be able to see much more of his great-aunts. He lived with them, in the spare room stuffed with knick-knacks from their travels, until such time as he was able to afford the deposit on a flat of his own.

Truth be told, had it not been that he felt a little bit shy about bringing dates home, Archie would happily have stayed in the sisters’ spare room forever. Joining them for a sherry or something stronger—“This needs much more vermouth, dear”—when he got home from work was the highlight of his day.

“How on earth can you enjoy living with two old biddies?” someone once asked him.

“They’re much more fun than people our age,” was Archie’s honest reply. People of the sisters’ generation were vastly more interesting than Archie’s contemporaries; so much more cultured. He would far rather listen to their stories than hear one of his peers yakking on about another lost weekend in Ibiza.

Modern music left Archie cold. Likewise modern literature and film. Thanks to the sisters, by the age of fifteen, Archie had read every important forties book and watched every forties movie anyone cared to name. Perhaps it was inevitable that Archie became a specialist in 1940s paintings.

Archie thought that the sisters had lived through the best of times, even if those times had included the Second World War.

Most importantly, the sisters taught Archie how to live life by their philosophy, which they in turn had borrowed from a fictional alley cat called Mehitabel. The Archy and Mehitabel books by Don Marquis that the sisters had enjoyed in their childhood became some of their great-nephew’s favourites too.

“One must be toujours gai, Archie, toujours gai.”

“Toujours gai” was Mehitabel’s motto and now it was theirs. It meant remembering there was no room in life for gloom or self-pity. Every opportunity for fun must be seized with both paws.

When Archie decided that he was actually toujours gay, the sisters were perfectly pleased about it and helped him navigate the delicate task of informing his parents, whom he rightly suspected would be less relaxed. He felt the sisters had saved him from years of parental estrangement with their careful intervention. For that alone he would always love Penny and Josephine dearly. He vowed to be there for them just as they had been there for him.

Chapter Three

That late April day in Sloane Square, post–Peter Jones debacle, Archie knew that what he had planned as a quick lunch was unlikely to be over before five. It was impossible to have a quick lunch at Colbert. After the sisters had both ordered steak frites with extra frites—they may have looked birdlike but their appetites were anything but, unless you were thinking “herring gull”—Archie excused himself from the table to call his assistant. Archie had his own gallery now and was considered an authority on the official war artists of World War Two. Once he’d given instructions to divert any calls for the rest of the day, he returned to the table and settled down for a lazy afternoon.

It was Josephine who asked the question this time.

“So, Archie, what excitements do you have for us today?”

It was the question the sisters always asked. Excitements was their term for any sort of social engagement and since Archie had somehow become their de facto manager, it was up to him to provide them. Sometimes it filled Archie with dread, hearing those words, when he didn’t have anything to offer or when he suspected that the excitements he did have planned wouldn’t cut the mustard. As two of a fast-dwindling number of Second World War veterans, the sisters were always in demand for speaking engagements but Archie knew they were both bored stiff of talking to university students and pedantic history buffs.

“Always the same bloody questions,” Penny would sigh. Sometimes within earshot of the unhappy questioner.

Penny in particular was dangerous when uninterested. Just the previous week, when a boy of eleven asked the sisters, as often happened at a school talk, “Did you ever kill anyone?” Penny had responded, “I could tell you but then I’d have to kill you too,” with such a cold look in her eyes that for a moment she even had Archie believing she could be a stone-hearted assassin.

Thank goodness that, today, Archie was sure he had an excitement worth getting excited about.

“Well, as I was saying to the nice young lady in Peter Jones . . . ” Young lady? She was almost certainly a decade older than he was. “You’ve both been invited to take part in the VE Day service at the Royal Albert Hall. Prince Charles and the Duchess of Cornwall will be in attendance.”

“Those two again?” Penny scoffed. “Given how few of us there are left these days, you’d think they would roll out Her Maj.”

“She is getting on a bit,” said Josephine, who was older than The Queen by two years.

“That’s true,” Penny agreed. “All the same. It could be our last time.”

You Might Also Like

Meet ‘Excitements’ Author CJ Wray

This long-time romance writer was inspired to switch genres by real-life sisters still having adventures in their 90s

Free: James Patterson's Novella ‘Chase’

When a man falls to his death, it looks like a suicide, but Detective Bennett finds evidence suggesting otherwise

More Free Books Online

Check out our growing library of gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety

More Members Only Access

Enjoy special content just for AARP members, including full-length films and books, AARP Smart Guides, celebrity Q&As, quizzes, tutorials and classes

Recommended for You