AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Thirteen

The journey to Paris went quite smoothly. Far more smoothly than Archie had dared to hope. Both his great-aunts were in a good mood and on good form, determined to be toujours gai for the occasion. Despite the slow start, Arlene had them both ready by ten o’clock, as promised. The taxi to Kings Cross St. Pancras was on time and the staff at the Eurostar terminal were top notch, ensuring that the sisters were whisked through security and border control on account of their advanced years. It never failed to amuse Archie that while for the most part his great-aunts were insistent on not being treated like “little old ladies,” when it came to cutting a queue, they were only too happy to jump into a wheelchair and have some nice young person whizz them past the hoi polloi.

LIMITED TIME OFFER: Labor Day Sale!

Join AARP for just $9 per year with a 5-year membership and get a FREE Gift!

At the other end of the trip through the Chunnel, there was a brief moment of panic when the disembarking Eurostar passengers were rushed by one of the beggar gangs that frequented the area around the Gare du Nord. Archie squawked with alarm when one of them targeted Penny and he thought he might have to intervene—he really didn’t want to have to get hands on—but Penny assured him that she had not parted with a centime when the young woman tried to sell her a “diamond ring” she claimed to have found on the station floor. It was a classic scam and thankfully Penny was wise to it.

“But you let her shake your hand!” said Archie. “That’s how they make off with their victim’s watches.”

Penny assured him that she still had her watch, which had been stuck at half past three since 1989.

After that excitement the Williamson party quickly found a taxi though the traffic was against them. The taxi driver blamed Madame Hidalgo’s “improvement works.” Thus the going was slow, but they did make it almost all the way to the Hotel Maritime before Penny started saying she needed to stop for a wee. They were on the Place Vendôme at the time. Archie tried to persuade Penny she could hang on for another five minutes but she was insistent. So they stopped the car and Penny spent a penny at The Ritz and then took twenty minutes to find her way back to the hotel lobby where Archie was just about to ask a Ritz employee to check that his great-aunt hadn’t come to some terrible harm in the ladies’. Then when they got back to the taxi, it was to discover that Arlene and Josephine were missing. While Archie went to find them—Josephine had also decided she needed to answer a call of nature—Penny disappeared again.

After a search lasting another half an hour Archie eventually found Penny in the Blanchet jewellery boutique on the other side of the grande place, chatting to a sales assistant in perfect French while trying on some baubles. There were dozens of glittering jewels laid out on the velvet tray on the counter. Archie appreciated the young assistant’s efforts to humour an old lady in a knitted beret but where on earth did she think Penny was planning to wear a diamond parure complete with tiara?

“Well,” Penny said, when they were outside and Archie admonished her for going AWOL. “I thought Josephine might be ages. She’s been complaining about her bowels since Ebbsfleet.”

“No she hasn’t,” said Archie, before Penny tapped out the SOS in Morse on his arm. “Ah, I see ...”

Josephine was apologetic when she and Arlene finally returned to the car.

“Never get old, Archie,” she said. “There’s nothing quite so frustrating as being unable to trust one’s own inner workings. Arlene and I were just saying there should be one of those app things. How many minutes to the next public convenience ...”

“Yes,” said Penny enthusiastically. “With star ratings. Archie, we could make a fortune.”

“It would certainly be useful,” Archie grumbled. “Now is everybody momentarily in control of their bodily functions and their faculties?”

The sisters and Arlene nodded. “Then allons-y.”

THEY EVENTUALLY ARRIVED at the Hotel Maritime in time for an early supper, over which Archie gave the sisters and Arlene their instructions once again.

“Ladies, tomorrow morning you will need to be downstairs for breakfast at 0800 hours local time. That’s London time plus one. I know that’s earlier than you would ordinarily prefer but we need to be at the Mairie by quarter past nine in order to go through security. Because of the level of dignitaries attending, there will be enhanced checks. For that reason, you should lay out the outfits you intend to wear to the inauguration tonight so that after breakfast you can change into them tout de suite.”

“I’ll be in charge of that,” said Arlene.

“Excellent. Aunties, I also think it would be a good idea for you both to hand over your medals to me right now so we know exactly where they are when we need them for the ceremony tomorrow.”

“We’ve kept those medals for seventy-five years, we’re not going to lose them tonight,” Penny grumbled.

“It would give me peace of mind,” Archie said, not mentioning the fact that in the thirty-five years he had known her, Penny had mislaid her medals on many dozens of occasions. Most recently they’d lain at the bottom of Flaubert the dachshund’s bed for at least three months, only coming to light when the old dog crossed the rainbow bridge and Penny was persuaded to throw away his tatty blanket. “I will sleep far better knowing exactly where they are,” Archie persisted.

Ordinarily, the sisters would have protested such infantilising measures, but they could both see that Archie was about to go into headless chicken mode so, after a quick shared glance, they did as he asked, dipped into their handbags and handed the medals over.

Archie looked at the medals with a critical eye. “I’ll give them a bit of a polish. This Italy Star hasn’t been the same since Flaubert got hold of it, Auntie Penny. That dog ...”

“Flaubert?” Arlene had joined the household after the dachshund’s demise. “I’ve always meant to ask ... That’s a very fancy name for a dog. Are you a big fan of French literature, Penny?”

“Something like that,” said Penny.

The two dogs before Flaubert had been called Browning and Walther, as had all her dogs before them in rotation since she bought her first dachshund puppy in 1966 (just after Connor died. It was easier than bothering to find another husband for company). She was still waiting for someone to make the connection and it was nothing to do with books.

PENNY WAS THE first to retire to her bedroom but she had no intention of going straight to bed. Archie had told her to “get some beauty sleep” but short of being put into cryogenic suspension, there was nothing Penny could do now to hold back the ravages of time. Besides Penny had things to do, plans to finesse. Tucked into one of the many pockets in her capacious handbag was the page torn from the Brice-Petitjean catalogue and an old but detailed floor-plan of the auction house building itself, which she’d printed from the internet during a visit to the library on the King’s Road.

For two-thirds of her very long life, Penny had promised herself that one day she would have vengeance. The only question in her mind was “when.” At last the universe had sent her an answer. Penny’s “when” was suddenly “tomorrow night.”

Chapter Fourteen

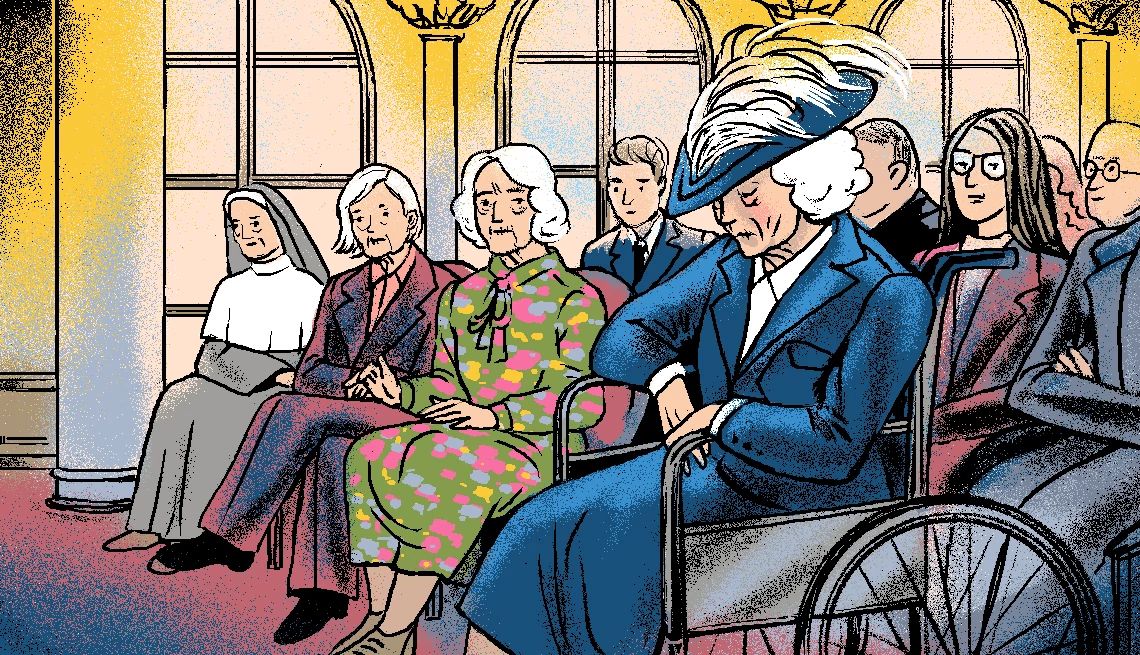

Alone at last in her own hotel room, Josephine fell into a reflective mood. It had been truly exhausting, staying toujours gai all day long for the sake of Penny, Arlene, and dear, dear Archie. All the same she knew that if she got into bed now she would not be able to fall asleep. Instead, she settled herself in a chair by the window. Archie had done very well with the hotel reservation and her room had a spectacular view over the rooftops of Paris. How unchanged those rooftops seemed even after so many years. Still so beautiful. But looking at that beautiful view made Josephine’s eyes prickle with tears, and she berated herself again for not having been braver, for not having insisted that she would really rather stay at home, in the face of Archie’s enthusiasm and Penny’s pouting. Apart from anything else, she wasn’t sure she entirely deserved to be invited to France to receive another medal. For quite a while now, Josephine had been far from certain that this seemingly endless appetite for celebrating World War Two was a good thing.

So many had lost so much, and the hope that revisiting their sacrifices again and again would convince their descendants that history must not be allowed to repeat itself didn’t seem to be working. Just as the Great War—H.G. Wells’s “war to end all wars”—had led inexorably to World War Two, the horrors of World War Two had far from ended the cycle of human violence. Instead, Britain’s part in the conflict had been reduced to a triumphant football chant—“Two world wars and one world cup”—combative and provocative; missing the point altogether. No matter how hard Josephine tried to emphasise the futility of war when she addressed school groups and history clubs, most people only seemed to take away the fact that this little old lady and her sister both knew how to strip a Sten gun. “How cool is that?”

Why hadn’t she made a stand and told Archie she’d had enough and asked him to say “thank you, but no thank you” to the kind Légion d’honneur committee?

It was because of Penny, Josephine told herself. Because all these excitements did seem to keep Penny going. Penny needed to be kept distracted. Always had. And it was for Archie too. After he had gone to such an effort to find something else for the sisters to look forward to, it would have been churlish to complain. He was so very good to them.

Josephine worried about Archie. What would he do when the sisters weren’t around anymore? She wished he could meet a nice young man who filled his days with love and happiness, so that he no longer felt the need or had the time to entertain two old haggises like his great-aunts. She offered up a little prayer to the god who hadn’t listened for a very long time. “Let Stéphane be single.” She was glad, at least, that the Légion d’honneur ceremony had given Archie a rock-solid excuse to be in Paris for that party at Stéphane’s auction house.

Thank goodness it was at least somewhat easier to be openly gay these days than it had been when Josephine and Penny were young. Life in the forties, the fifties, even the so-called “swinging sixties” had been so strictly bound by moral certitudes that birthed so many toxic secrets and ultimately caused nothing but damage. Looking out over Paris, Josephine thought of the toxic secrets she herself had kept over the course of her lifetime—was still keeping in some cases—her own secrets, her husband Gerald’s secrets, her sister Penny’s secrets. Even those of Penny’s secrets that Penny had no idea Josephine knew. Josephine understood that she and Penny couldn’t have much longer to go on now. Was it time to let some of those secrets out into the light?

As she asked herself that, Josephine considered that perhaps subconsciously she had wanted to come to Paris all along; to share her own darkest secret in the place where it all began.

Pressing her thumb against the edge of her lucky shrapnel for comfort, Josephine thought back to the last time she’d been in the city. July 1947. She’d been to France a few times since, most notably to the south the summer Penny’s husband, Connor, died—oh, what a terrible business that was—but not Paris. She had thought she would never be in this city again.

Chapter Fifteen

Paris, 1947

At Christmas 1945, when Penny finally returned from her FANY posting in Italy, the sisters were reunited for the first time since 1940. Josephine had not moved back to the family home after being demobbed, preferring instead to stay in London, where she was working as a secretary for a firm of accountants. She waited until Penny arrived from overseas to make the trip to the countryside and the big stone house that had been their childhood home. Both sisters looked forward to seeing George, who was over the moon to have his big sisters with him again. Sheppy, now an old dog, was likewise thrilled to see them.

However, there was tension between the sisters and their parents. Their father in particular didn’t seem able to appreciate that the war had turned his girls into women, with their own ideas and opinions about what to do next. Penny’s time with the FANY in Algiers and then in southern Italy had given her a passion for travel. Much as Ma and Pa would have preferred it, there was no way she would ever settle for a husband and the Home Counties now she’d seen what the rest of the world had to offer. On Christmas Day, she told them that she’d accepted a job in Germany, in the British sector in Hamburg, with an organisation that helped to rehome people displaced by the war. Needless to say, there was plenty of work to be done on that front.

As for Josephine, she simply couldn’t pretend that things would ever again be as they had once been, much as she wished she could and even though she believed Pa didn’t actually know what had happened in the spring of 1940, while he was stuck in France. Ma had at least promised her that. Josephine had come home for Penny and for George. That was all.

She was glad to go back to London after a couple of days. Waiting for her at the house where she rented a room was a letter from the University of Cambridge, offering her a place to read English on an ex-service grant. There was another letter too. This one was from her dear friend Gerald Naiswell, containing a marriage proposal that broke her heart, even though she knew for sure she hadn’t encouraged it.

She’d met Gerald while she was working in the plotting rooms in Plymouth, when his submarine, HMS Uriel, docked for repairs and Josephine’s Wren colleagues dragged her along to a party on board. While the party roared in the narrow, stuffy mess, she and Gerald sat and shared a quiet cigarette on the conning tower. They’d become firm friends since then but they’d never been lovers. But here he was, proposing marriage.

My darling Josephine, I might not be the husband you hoped for but I feel sure I could be the husband you need and you, in return, could be my ideal wife. Please say you agree. I know this is not the most romantic proposal and I’m sure you must have hoped for better, but I also think that we could make each other very happy indeed. I promise I will always be your safe haven if you only say you’ll be mine. Just say the word.

Josephine sent her “no” by return. She wrote that she hoped she and Gerald would be able to stay friends but her heart still belonged to one man and one man only. He knew that. Just as she knew why Gerald’s heart could never really be hers.

EIGHTEEN MONTHS AFTER that uncomfortable first post-war Christmas, Penny was still in Germany and did not have time to come back to England for a visit, so she proposed that Josephine meet her in Paris for the second week in July.

“I’m not sure it’s a good idea,” Josephine wrote. “It won’t be the same as it was in 1939.” She stopped short of giving her real reasons. Penny still had no idea what had happened in Scotland.

Penny wrote back at once. “Don’t be such a rotten spoilsport, Josie-Jo. Aunt Claudine says they’d be so pleased to have us and I would be really pleased to see you. Work has been terribly difficult lately and I need to have some proper fun. Come to Paris. If it’s awful, we’ll jump on a train to Biarritz. I’m paying for everything and I promise it will be totalement gai.”

After a flurry of letters, Josephine had given in and agreed to the plan. Looking back in later years, she would understand that there must have been a part of her that did want to go to Paris, that wanted to know for sure. But for a month before her rendezvous with Penny, she would wake in the middle of the night, every night, and wonder what she might find in the city she had tried to forget. The creeping dread she felt in the small hours started to seep into the day. She was constantly distracted. She couldn’t concentrate on her studies. Her heart told her with every beat that it was a bad idea to go to France. A very bad idea indeed.

Josephine had not heard from August Samuel since February 1940. After her mother found out that Augustine was in fact a boy—there was incontrovertible evidence of that—she was forced to write a letter telling him she no longer wished to be in contact. Then Cecily sent Josephine to Scotland to “think about her future.” Whenever she could—and it wasn’t easy under the constant vigilance of her Victorian grandmother—Josephine sneaked letters to August. Connie Shearer had acted as go-between.

Josephine had sent one last letter in March 1940 but there had been no response. Seven years had passed since then. The reasons why August might not have written in that time were many but none of them were good. Either he’d decided that he no longer loved her—and in the light of her last letter from Scotland that would hardly be surprising—or something far worse had happened. She hoped it was the former. Even after all the awful things that had befallen her because she had fallen in love with him, she still wished him happy and well.

The night before she was due to leave for France on the ferry train from Victoria, Josephine pulled her old suitcase from under the bed and found the secret hiding place in the case’s silken lining. She hadn’t looked at August’s letters since the summer of 1940, when she realised he wasn’t going to turn up and save her like a knight in shining armour on a stupid white horse, and to see his curly handwriting suddenly became more of a torture than a comfort. Before then, she had read those letters so many times that she knew them by heart and their creases were so worn that the light shone through.

She tried to read the letters now but found she still couldn’t bear it. Instead she tucked them back into their hiding place and started to pack the things she would need for her trip. Her clothes, her notebooks, and her courage. She had to go to Paris whether she wanted to or not. It was too late to let dear Penny down. She suspected from the tone of her little sister’s most recent aerogram that Penny really needed her to be there. That was Josephine’s excuse.

UNLIKE POOR OLD London with its bombed-out terraces that looked like broken teeth in a tired and dirty face, Paris had at least escaped the worst attentions of the Luftwaffe. Though the city was decidedly grubbier than Josephine remembered, it was still very much recognisable as its beautiful self. Life had come back to the grand boulevards. The cafés were buzzing. People were ready to enjoy themselves again.

“I’ve been so looking forward to seeing you,” Penny said, as they whizzed up the Champs-Élysées in a taxi. Uncle Godfrey and Aunt Claudine had moved back into their old apartment and that was where the sisters would be staying, sharing a room again for the first time since the summer of ’39. Penny was excited but Josephine was not at all sure how she would feel when she walked into the courtyard of 38 Rue du Mont Olympe.

As the sisters got out of the car, Penny looped her arm through Josephine’s and brought her close. Though Penny had not mentioned August’s name once as they made their plans for the trip, and had continued to steadfastly avoid the subject on their taxi ride, Josephine took that gesture to mean her sister did perhaps understand how hard this was going to be.

An unfamiliar concierge let them through the gate that day. Walking into the communal garden where so much had happened, Josephine couldn’t help but turn to look at the names on the letterboxes. Her eyes automatically flickered to the top row. Where once had been written “Famille Samuel,” now there was a different name. Though not a stranger’s name exactly.

“Declerc.” Josephine said the word out loud. “Oh. That’s a coincidence,” said Penny.

Josephine felt her heart ache as she looked at that nameplate and tears pricked at her eyes. Penny noticed and clasped Josephine’s arm a little tighter.

“Toujours gai.”

AUNT CLAUDINE WELCOMED them with kisses. Though she was as beautiful as ever, the war years had left their mark on her, overlaying her much celebrated beauty with an ethereal veil of sadness. Two of Claudine’s brothers—Ernest and Roland—had died in The Battle of Normandy. Josephine and Penny remembered the young men well. At Godfrey and Claudine’s summer wedding back in 1932, Claudine’s brothers had each scooped up a little Williamson girl for a riotous piggyback race around the garden. Now they were forever frozen in time, forever in their twenties, smiling out from portrait photographs in their smart army uniforms, in a sitting room that was much smaller and darker than Josephine remembered.

“How wonderful to see you both,” Claudine said.

“Good to have you here, girls,” agreed Uncle Godfrey. “Bringing some life to the place.”

Godfrey was not the man he had once been. He was much slimmer and had lost a lot of hair since they’d last been together in this room. When he kissed Josephine on the cheek, she smelled alcohol on his breath, though it was still only ten in the morning. Indeed, while Claudine brought coffee to her visitors, Godfrey remained in the kitchen, adding another slug of brandy to his elegant porcelain cup, then knocking back another one direct from the bottle. When he came to join his wife and their guests again, he bounced off the door frame on his way into the room.

“Who put that there?” he joked, but Josephine could tell he was embarrassed.

They exchanged news of Penny and Josephine’s parents and of George, who was finally in the army but finding it a lot less exciting than he’d imagined back when he was eleven years old pretending to shoot German paratroopers out of the sky over the kitchen garden. His regiment had been posted to Malaya and his letters home were full of complaints about the heat, the food, and the leeches.

Then they spoke about their war. Godfrey told the sisters how proud he was they had both gone into the women’s forces. “Not that I’m in the least bit surprised. You were always both fine young women with a proper sense of duty.”

Penny took Josephine’s hand and squeezed.

Claudine seemed much more tender with her husband than Josephine remembered. There was no mention of her painting—the hobby that had obsessed her in the summer of 1939. The sisters knew better than to ask after Monsieur Lebre, though privately Josephine wondered what had become of him. In 1939, he must have been in his twenties. Had he joined up the moment France entered the war? Had he taken part in the Battle of France? Or had he been shipped off to Germany to join the groups of young French men forced to labour for the Axis powers? Had that been the fate of their old friends August and Gilbert too?

You Might Also Like

Meet ‘Excitements’ Author CJ Wray

This long-time romance writer was inspired to switch genres by real-life sisters still having adventures in their 90s

Free: James Patterson's Novella ‘Chase’

When a man falls to his death, it looks like a suicide, but Detective Bennett finds evidence suggesting otherwise

More Free Books Online

Check out our growing library of gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety

More Members Only Access

Enjoy special content just for AARP members, including full-length films and books, AARP Smart Guides, celebrity Q&As, quizzes, tutorials and classes

Recommended for You