AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Twenty-Five

The training course might be being held in a requisitioned mansion house but this was to be no country house party. The morning after her arrival, Penny was shaken into wakefulness at five. Before breakfast, she joined her new colleagues—all but one were men—for a four-mile run around the manor house grounds. It had been a long time since Penny had to do a run, the ground was boggy from all the recent rain, and by the end of the third mile she was ready to go back to bed. Last to the finishing line, she barely had time to retie her bootlaces—they would not seem to stay put—before the recruits were instructed to line up at the start of an obstacle course.

LIMITED TIME OFFER: Labor Day Sale!

Join AARP for just $9 per year with a 5-year membership and get a FREE Gift!

“Here we go,” said the other woman, who introduced herself as Francine. “I hope you don’t bruise easily.”

Penny watched as the first six candidates in their group—all at least a foot taller than she—attacked the course. It was considerably harder than anything she’d ever tackled at St. Mary’s or during FANY basic training. And unlike at school, there was no point trying to get out of it by mouthing “monthlies” at the trainer.

“Bruna! Bruna!”

It took a nudge from one of the men to remind her that that was her new name.

“Isn’t that you, sweetheart?”

Penny would soon come to learn that in this place, “sweetheart” was never meant as a term of affection.

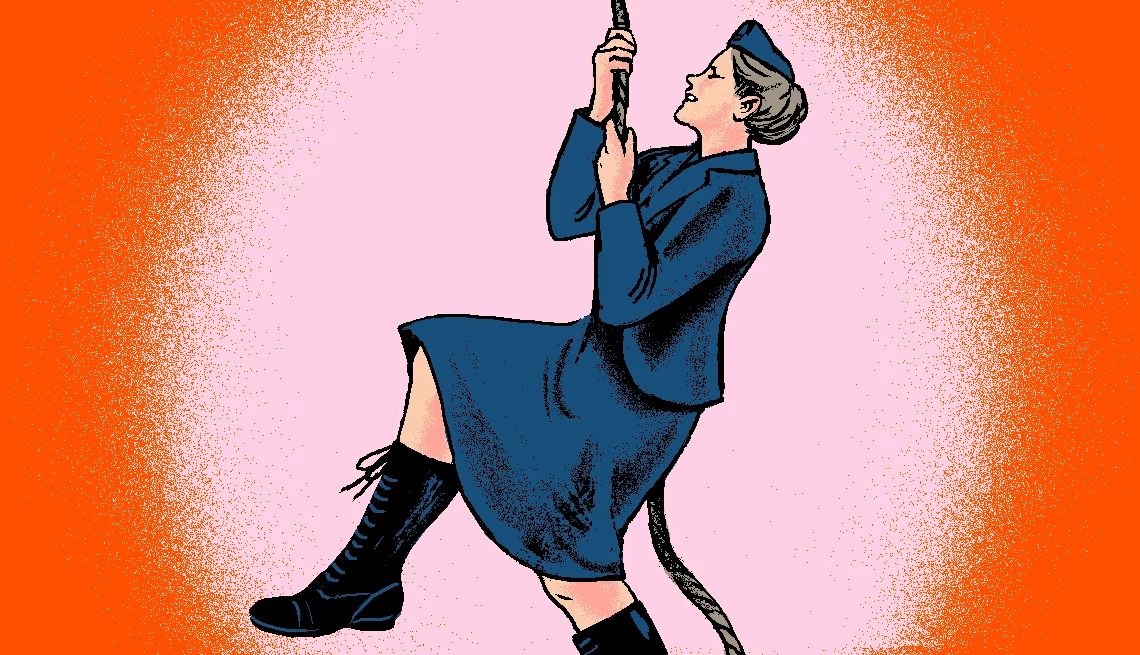

That first morning was awful. Despite watching her new colleagues closely to see how they handled the course, as Penny approached each obstacle, her mind went completely blank. Even the simple rope swing, which should have been right up Penny’s street, was difficult. The rope was wet and slippery and she couldn’t get a proper grip. Her hands were soon covered in burns from the rain-sodden sisal. Her legs were still weak from the run, like cooked spaghetti. Why were her boots, which pinched and rubbed, so heavy? Penny seemed to spend a lot of time face down in freezing mud. Why was she even there? Could she ask to be sent back to London now?

“Don’t even think that. You’ve been called to serve your beloved France.” Penny was giving herself a pep talk when she was knocked off a six-feet-high wall by a real commando who pretty much landed on top of her. Face down in the freezing mud again.

But Penny could not let any height, depth, length, or weight get her sent back to FANY HQ. Being chosen for this assessment was the most exciting thing that had happened to Penny in her life. Thus she would climb, jump, dive, do whatever it took . . . Though every new obstacle looked as though it would kill her, she reasoned that it had not been designed to do so. She was not on enemy terrain. Not yet. She might get hurt. She might limp away covered in bruises—she was already covered in bruises—but they would fade. Even a broken bone would heal in time. Why would she have been sent to this place, if only to be killed off on the first day?

“Toujours gai,” she muttered to herself as she threw herself at the rope swing one more time.

THOUGH IT SEEMED on many occasions as though she had reached the limits of her endurance, Penny stayed the course and was not sent back to London afterwards. Instead she was moved straight on to another training course at another country house. This time in Oxfordshire. There was more PT—endless PT—but now there was coding and telegraphy to master too.

Penny had to learn to use radio equipment—and know how to repair it—and get her Morse code up to speed. She’d previously been quite pleased with her coding rate of ten words per minute. Now she had to double that. She and Francine took it in turns to hold the stop-watch and monitor each other’s pace and accuracy for hour after hour after hour. The Morse training was so intense that after a couple of days Penny found herself tapping out her thoughts as she tried to get to sleep.

Theoretical training was delivered entirely in French, reminding the candidates that once they were deployed behind enemy lines—as fully-fledged SOE “F Section” agents. The “F” was for France—their cover would depend on their being able to pass as locals. Trainers instructed the candidates in French slang and social etiquette. The students were also brought up to date with the current rules in occupied France. They could not risk being caught out by not knowing, for example, that it was now illegal to order alcohol on a Sunday or that French women were not permitted to have a cigarette ration. There were a great many things to learn.

Over the next few weeks, Penny perfected her French accent—modelled on the voice of her godmother, right down to the little intakes of breath she made at the end of each sentence. She decided she would use elements of Aunt Claudine’s family history in her official back story too. It was important for a back story to feel real and thus including fragments of an agent’s real story was useful.

Soon Penny’s Morse speed was the fastest her telegraphy instructors had ever seen and while she would never be the quickest around the obstacle course, she had learned that taking just a couple of seconds to properly evaluate a situation before she tackled it could make all the difference between successfully jumping a gap between one wobbly platform and the next or landing on her bottom in the mud.

Meanwhile, there were other, more surprising, skills to master. Three times a week, Penny’s cohort attended lectures on disguise, forgery, burglary, and house-breaking.

“Nice to have a trade to fall back on when we’re done with the war,” a fellow trainee quipped.

It was rumoured that some of the house-breaking trainers had actually been criminals before they were asked to lend their skills to the pursuit of victory.

There was weapons training too. Penny had grown up around guns— they were an essential part of country life—but she’d rarely been allowed to shoot. When her father went game-shooting, only her younger brother George was allowed to tag along, unless they were short of beaters. So this was new. She was gratified to discover she was good at it.

Penny was hurriedly trained in the use of several types of gun—both the guns she might be provided with by her handlers (though arming women in the field was still controversial) and the guns she might come across in the hands of the enemy. If she somehow managed to wrestle a Walther P-38 off a German officer, she had better know how to use it. Likewise the Flaubert pistols used by the French police. A whole afternoon was spent learning about the French police, and their more dangerous cousins the Milice, their ranking systems and how to recognise where they stood in it. In the occupied zone, certain of the French were just as much the enemy as the Germans now.

It wasn’t long before Penny could strip a Sten gun as fast as anyone and fire four different makes of handgun with deadly accuracy. She easily convinced her trainers that she could handle herself in a gunfight, but what if she was without a weapon?

She was about to find out. Three months after that first strange meeting in the mansion block, Penny was on her way to Arisaig to spend several weeks devoted to guerrilla training, specialising in explosives, evasion, and silent killing.

Chapter Twenty-Six

On the first afternoon in Scotland, the instructor who would be leading the F Section candidates through their advanced training in unarmed combat and silent killing introduced himself as “Frank.” He didn’t look like a Frank, Penny thought. More like a Douglas. He was tall and fair with movie star looks. If a movie star hadn’t been able to find the right doctor to reset his nose after a fight.

As Frank outlined the work that lay ahead of them, Penny was thrilled to hear he was going to be teaching them combat techniques based on the methods of Major Fairbairn. Frank claimed he had worked with Fairbairn in the Shanghai Municipal Police.

“My job is to send you all away from here with the skills of a ninja,” Frank said. “Unfortunately, I have a matter of days rather than years and, looking at you lot, nothing like the right kind of raw material.”

The male candidates shifted and grumbled. They didn’t like the suggestion they weren’t already the best of the best. Penny too stood a little straighter, determined to prove this Frank chap wrong.

“The first thing I want to impress upon you is how important it is to listen to me carefully,” he said. “There is a fine line between practising your combat skills and accidentally committing murder. Not that I think any of you will master the techniques first time round but you never know. I want you to do everything with only half the force you’ll use in the field. So, which one of you would like to be first up?”

Penny could have predicted the first volunteer. It was the trainee agent codenamed Jerome, an American. From the moment she met him, Jerome had teased Penny mercilessly and not in an entirely friendly way. He seemed affronted to have to train alongside women. Now he stepped forward and stood in front of Frank, making himself large. He had a whole head in height on Frank. He was broader too. He was smiling widely and chewing gum, as though getting ready to fight off the advances of an optimistic twelve-year-old.

“I’d take that gum out if I were you,” said Frank. “Don’t want to choke.” Jerome continued to grin but tucked the gum behind his ear.

“OK, my friend,” Frank began. “Come at me from the front and try to get me in a two-handed stranglehold.”

“Try?” Jerome turned back towards the other candidates, playing to the audience. “Tell me when you’re ready.”

“I’m always ready,” said Frank.

Jerome rushed at Frank with both hands out in front of him. Before anyone had a chance to draw breath, Jerome was on the floor.

Frank addressed the others. “If someone is coming at you from the front like that, with their hands out, they’re telegraphing their intentions and they’re already unbalanced. All you have to do is tip them that tiny bit further.”

Jerome was still on the floor. “Nice try,” said Frank.

Jerome wasn’t grinning anymore.

One by one, the trainees did their worst and Frank planted every single one of them on their backsides in the dirt. There was something about the spectacle of one man fighting off so many others as though they were gnats that made the male trainees eager to take their turn and be the one to reset the balance. It was a while before Penny found her way to the front of the queue.

“I hear you already have some experience in Defendu, Agent Bruna,” Frank joked. “Remind me not to ask you to the theatre.”

“I don’t think being able to defend oneself is a laughing matter,” said Penny.

“Of course not. Though perhaps one ought to be more discerning when it comes to telling the difference between a deadly enemy and an amorous army man.”

“Is there a difference?” Penny asked. “For a woman?” Frank had no answer for that.

Penny waited for her instructions.

“OK,” said Frank. “I’m going to come at you from behind and I want you to deflect me. Are you ready?”

“Always ready,” she said, parroting his own words. She turned her back on him and pretended to be adjusting a pair of imaginary gloves to add a bit of verisimilitude to the scenario.

“Oooof!”

Though Frank had spoken softly, he did not come at her softly at all. He tackled Penny with every bit as much speed and power as he had tackled the boys. Penny was on the floor before she could blink. There wasn’t any time for her to adopt a defensive stance. Definitely no time to come up with a counter-attack. This was very different from training with George and the evacuees in the garden back at home.

“Bastard,” she muttered.

While Frank was turning to explain her mistakes to the others—“Feet too close together. Not ladylike to stand like this, I know, but you’ve got to . . .”—Penny saw red. Still on the ground, she hooked her right foot through Frank’s open legs and around his right ankle, before yanking as hard as she could.

Frank, caught totally by surprise, lurched forward. Penny followed up by using her left foot to kick him in the arse. He landed on his knees. While he was down, Penny quickly scrambled to her feet and adopted a pugilist’s stance.

“Always ready,” she said. The other trainees cheered.

Standing up again, Frank conceded the point. “And that’s the kind of spirit you’ll need to demonstrate in the field.”

AS THE MORNING went on, all the trainees stayed on their feet for longer. Frank introduced the scenarios, demonstrated on a brave volunteer, then sent them away to practise in pairs. After Francine, the only other female trainee, was paired with one of the men, Penny was left alone. None of the men wanted to be paired with the girl who had brought Frank down, lest she leave them similarly red-faced.

So Penny had to practise with Frank himself. He continued to make no concessions to her relative size. The enemy wouldn’t, after all. Every tackle was as hard as the first one, forcing her to put every ounce of her weight behind her punches and her kicks. By lunchtime, she knew that beneath her green overalls, she must be black and blue. Thank goodness, she thought, when Frank told the class that “silent killing”—that afternoon’s topic— required less brute force and more cunning.

“I think you’ll be rather good at it,” Frank told her.

AFTER LUNCH, THEY were given a presentation on pressure points and shown exactly where to apply one’s fingers to cause someone to black out within seconds. Penny watched intently, marvelling at the fragility of the human body and how easily a life could be snuffed out. How quietly.

Later that same afternoon they were introduced to a new weapon. Designed by W.E. Fairbairn himself, with his colleague Eric Sykes, the double-bladed Fairbairn-Sykes fighting knife was the ultimate commando tool. It was easy to wield, hard to drop unintentionally. It could be used to stab or slice. It could break the skin with only the slightest pressure . . .

“Right, silent killing,” Frank continued as most of the trainees tested their new blades on their thumbs and tried not to let on that they’d cut themselves. “So called because the trick is to cut the windpipe so your victim can’t draw breath to scream.”

“Sounds good,” said Jerome.

“It shouldn’t sound of anything at all.”

Penny paid closer attention to Frank’s instructions now than she had ever paid to anything in her life. Her old teachers at St. Mary’s would not have recognised her in such an attentive mood. This time, when Frank called for volunteers, they were in short supply. There was something about the glittering blade of the F-S knife that unleashed a primeval anxiety.

“Agent Bruna?” Frank called Penny to the front. “If I may?”

Penny was every bit as nervous as the men who stepped back to let her be first but she would not let them know it. She stood in front of Frank with her feet apart and braced. Taking her by the elbow, he quickly whipped her round, as if in a dance move, so that her back was against his chest and her neck encircled by his elbow. He tipped her head back and brought his sheathed blade to her throat.

“Here.” He pointed with the tip to the best place to cut.

He let Penny go. Shaky with shock and relief, she staggered back to the line-up.

“Hang on,” said Frank. “It’s your turn.”

“My turn?”

“To try to kill me.”

To the amusement of the other trainees, Frank pulled a lipstick out of his pocket and used it to swipe colour along both sides of the leather sheath of his knife. “So you can see your mark.” Then he handed the blade to Penny.

“Do your worst, sweetheart.”

“Sweetheart?”

Frank turned his back on Penny and went to walk away. Flooded with anger and adrenaline, Penny went after him. In two steps, she was on his back like an angry cat. She pulled his hair to jerk his head back and used the sheathed knife to draw a line across his neck. When she let him go, he crumpled to the ground in such a way that when Penny rolled him over and saw the slash of red across his bristly throat, for a moment she genuinely believed she had killed him.

“Bloody hell,” murmured one of the other candidates. The rest were silent until, at last, Frank sat up, coughing.

“Not bad,” he said. “Not bad.”

FRANK JOINED THE candidates for dinner that evening. Everyone wanted to be near him. They all wanted to hear his stories of working with the great man Fairbairn. They all wanted to know how often Frank had had to use his silent killing methods in the field.

“I think we all know it’s not in good taste to keep a tally,” he said, which Penny suspected was calculated to make his awed trainees sure the number must be in the hundreds.

Penny tried not to stare at Frank. She pretended to be interested in the conversation at her end of the table. However, whenever Penny allowed herself to glance in Frank’s direction, she always found he was looking back at her. Usually, they both looked away quickly, but once—one glorious time—he sent her a small smile.

“Come on, Frank,” said one of the men, after much wine had been drunk. “Tell us how we did today. Tell us which one of us you think is going to make the best agent.”

“I have no doubt that every one of you has what it takes,” Frank said diplomatically. He was doing his best not to be drawn.

“But some of us are ready to go hand-to-hand with the Nazi bastards, eh?” the candidate persisted. “While some of us should just stick to fiddling about on the radio.” That brought a laugh from the men at Frank’s end of the table. The other female candidate, Francine, rolled her eyes for Penny’s amusement.

“Well, I’ll tell you one character trait that’s of no use in the field whatsoever,” Frank said. “And that’s arrogance; a trait some of you have by the bucketload. All of you still have a lot to learn before you come anywhere near the skill of the agents already in France.”

There was grumbling at the mild ticking off.

“But Frank,” said Jerome. “You must have your ideas. Come on. Just one name. I’ve got money riding on it.”

So the men were running a sweepstake. The women had not been asked to place their bets.

“OK,” said Frank. “If you really want to know.” The men hammered on the table. They did.

Frank shook his head, but right afterwards he looked straight at Penny and everybody knew.

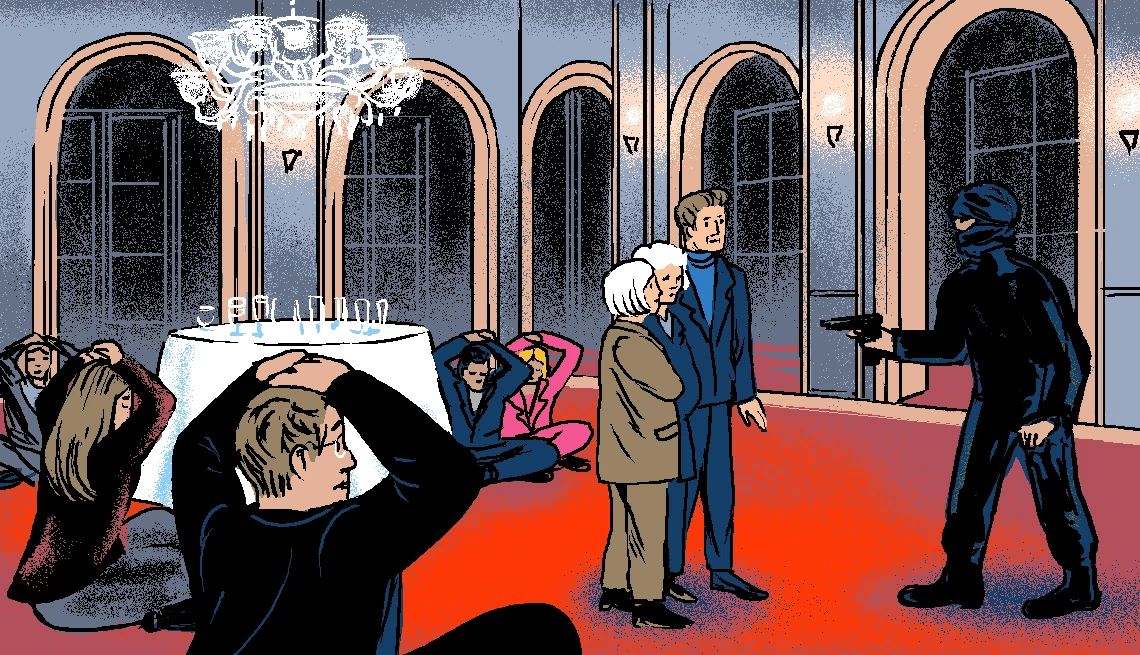

ON THE WAY back across the courtyard to the dormitories, two of the male candidates jumped Penny and Francine from behind. Francine shrieked, struggled and was quickly released, but the man who had hold of Penny did not let her go so easily. Instead, he pressed his elbow harder and harder against her throat. It was Jerome. Of course it was.

“Teacher’s pet,” he hissed in her ear.

Penny stamped down hard on his instep with the heel of her boot. Howling with indignation, Jerome loosened his grip and hopped away swearing.

“Bastards,” said Francine. “Who needs the Germans when we’ve got that lot on our side. Are you hurt?” she asked Penny.

“Not as badly as Jerome’s ego must be.”

After Francine went to bed, anticipating another day on the assault course, Penny remained outside alone. She needed a cigarette. She found a quiet place well away from the main house, sat down in the shelter of a wall, and gazed out into the darkness until her eyes adapted and the shadowy hulks of the mountains became just visible in the gloom.

Penny blew smoke rings, suddenly remembering that soldier she’d met on the train back when she was still a schoolgirl. He’d blown excellent smoke rings. What happened to him, she wondered? She couldn’t remember his name. Had he ever told her?

She thought about Josephine, down in Plymouth working in the Western Approaches plotting room and going to parties on submarines. It sounded like more fun than her former job at WRNS HQ. She thought of their father still overseas. When would he next be home? Would this war be over before George had to sign up and fight? Though she knew her little brother probably relished the prospect as much as she once had, she very much hoped that George would never have to go to the front line.

Hearing the rustle of someone approaching, Penny sank back into the shadows, hoping she wouldn’t be noticed. Too late. The glowing tip of her cigarette gave her away. She’d extinguished it slightly too slowly.

“Mind if I join you?” It was Frank.

Penny scooched along the stone bench. Frank tapped a couple of cigarettes out of his packet of Players and handed one to her.

“I saw what happened with Jerome. I don’t think I made you very popular with your classmates.”

“I don’t think I was very popular to begin with,” Penny said. “I don’t understand it. We’re all fighting for the same cause, aren’t we?”

“Let’s hope so. Need a light?”

Frank didn’t have a lighter. He had an old-fashioned silver matchbox, like the one Penny’s grandfather carried. In the glow of the match he struck against it, Penny saw that it was engraved.

“Can I have a look?” she asked.

“Of course.” He handed it over. It was inscribed with a verse from a poem.

In the fell clutch of circumstance,

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

You Might Also Like

Meet ‘Excitements’ Author CJ Wray

This long-time romance writer was inspired to switch genres by real-life sisters still having adventures in their 90s

Free: James Patterson's Novella ‘Chase’

When a man falls to his death, it looks like a suicide, but Detective Bennett finds evidence suggesting otherwise

More Free Books Online

Check out our growing library of gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety

More Members Only Access

Enjoy special content just for AARP members, including full-length films and books, AARP Smart Guides, celebrity Q&As, quizzes, tutorials and classes

Recommended for You