AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Forty-Three

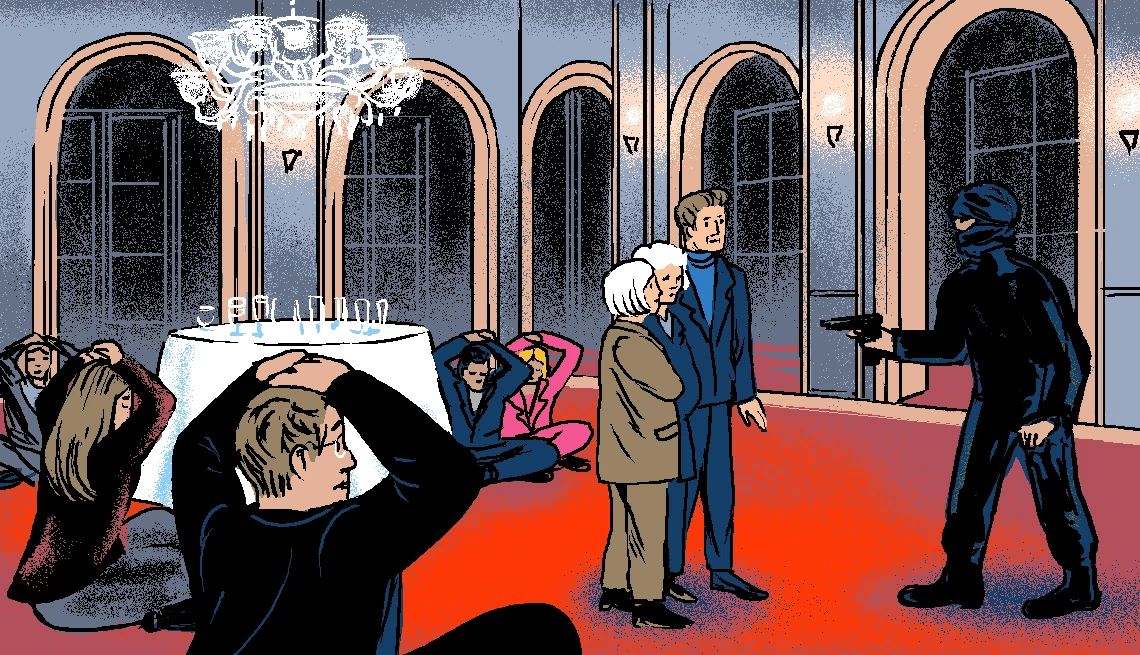

Inside the auction house, the captives had no idea that the police were mustering outside, along with two elderly veterans and a hen party. They were all watching the clock, as ten minutes passed, fifteen minutes, twenty ... Were they witnessing the last ten minutes of a poor old lady’s life?

Not if Penny could help it.

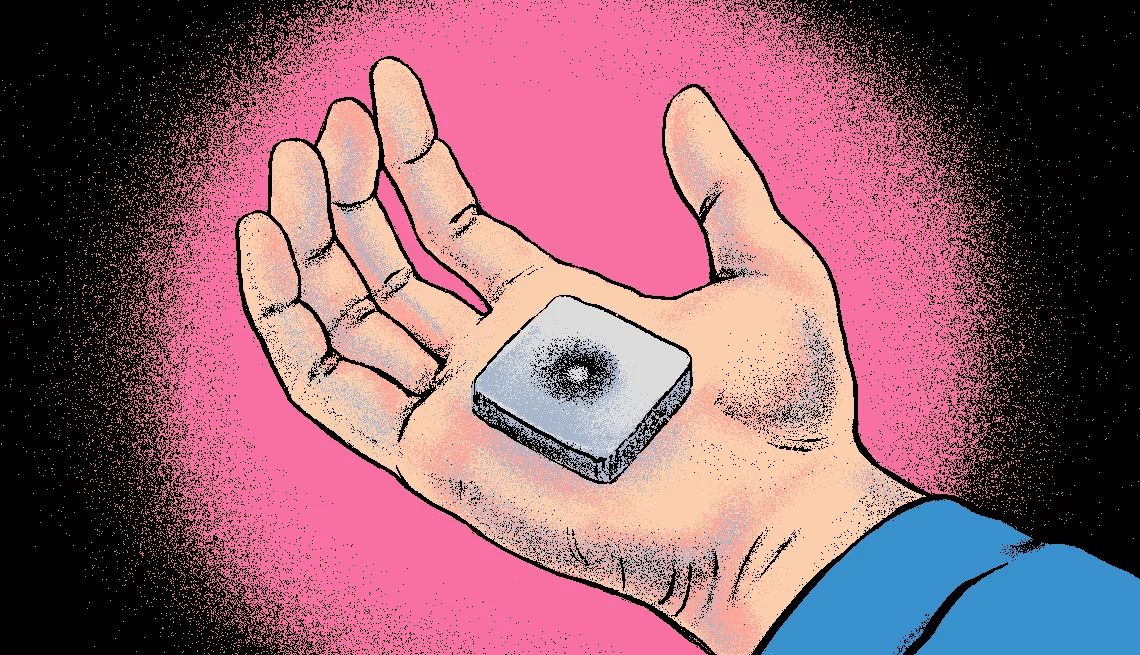

She had her plan now. Slowly, so as not to draw attention, Penny opened her handbag and reached inside it for her metal matchbox. She’d had it close to hand, day in, day out, for almost sixty years; ever since the day that Jinx brought it to the house in South Kensington, saying, “Frank would have wanted you to have this, not me. He loved you, Penny. You were the love of his life.”

LIMITED TIME OFFER: Labor Day Sale!

Join AARP for just $9 per year with a 5-year membership and get a FREE Gift!

Penny had hoped never to have to use it for anything more serious than lighting a cigarette but here she was. In a different context, she thought she would have liked Angel, but he had threatened her life and the lives of everyone in the room. And if she died, who would be next? Anyone who threatened the health or happiness of Archie or Josephine would have to come through her on their way into hell.

Just as on that long-ago day when Alfred the army man grabbed her by the thigh, any fear Penny might have felt had been replaced by a low electric fizz of excitement. If this was to be her last action, it was going to be one worthy of the F Section agent she should have been, would have been, were it not for Frank’s foolish attempt to keep her out of trouble. The young girl who’d broken her date’s nose in the theatre back in 1942 was still within her, and that girl remembered exactly how to knock a man out with a metal matchbox turning her fist into steel.

Angel would not know what hit him.

Penny rehearsed the matchbox knockout in her mind as she rifled through her bag. Mental rehearsal was key. Calm, slow breathing. Focus. Deadly accuracy. She needed to get just one good strike to Angel’s jawbone while parrying away his gun with her other hand. She could do it.

But the matchbox was not in Penny’s bag that night. It was in her great-nephew’s breast pocket.

“HELL’S TEETH.” Penny cursed under her breath. How could she have forgotten she’d given the matchbox to Archie just that afternoon? Her best weapon, gone. What could she use instead? Cough sweets? That bloody copy of Fifty Shades of Grey? Perhaps if she read him a particularly shocking passage ... What about a pen? She had no pen either. Her Swiss army knife was back in South Kensington. “You won’t get that through security,” Archie had warned her, as they packed for the journey. She’d let him persuade her not to try. Now here she was with absolutely nothing left to work with.

“Pen?” Penny tapped to her sister.

“No,” Josephine tapped right back.

“Hair pin?”

“No!”

“Cheese knife?”

“No!”

ARCHIE WAS OBLIVIOUS to the sisters’ frantic messaging behind him. In front of him, Stéphane’s face shone out from the sea of frightened faces. Archie chanced a little smile in his direction. Oh, Stéphane. Was this really how it was going to end?

Archie had never been very good at sitting on the floor and after nearly half an hour on the hard parquet, he was starting to lose sensation in his buttocks. He knew it was nearly half an hour because, like everyone else, he had been watching the clock on the wall, wondering if Angel’s thirty minutes was a real deadline. Was anybody out there going to give in to his demands or at least suggest they might with a bit of negotiation? Did they even know he was making those demands? Of course they must. Angel was beaming his phone footage straight to Facebook. The world would be watching the countdown, possibly with popcorn at hand. Wasn’t that how it worked these days?

“Twenty-nine minutes are up,” Angel addressed his phone and the audience beyond. “And it seems to me that you don’t think I’m serious. And so we come to the final minute,” he said. “Sixty seconds until this elderly woman meets her maker.”

“I don’t think he’ll have me,” Penny said.

“Sixty seconds, starting now ... fifty, forty-five, thirty, fifteen ... Bye-bye, Grandma.”

“No! No! I won’t have it!” Suddenly Archie was on his feet. And then he was flat on his back.

But the distraction of Archie’s unexpected fall was all the opportunity Penny needed to jump up and punch Angel in the kidney, with or without a weapon. She knew how to make a good fist. While Angel stared down at Archie, Penny made her move. But she didn’t get as far as punching anyone. Instead as she leapt up, she gasped in surprise as a pain like the point of a compass in the middle of her chest made her slump back in her chair. She clutched at her chest. Angel lowered his gun.

Josephine tapped, “SOS.”

Penny didn’t tap back but kept her hands pressed to her heart. She closed her eyes and muttered, “Dear God, at least save Archie.”

This was one fight she was not going to win.

Chapter Forty-Four

As he came back to consciousness on the hard wooden floor, for a second or two Archie had no idea where he was. When he did remember, he gasped in distress. He was under siege by some maniac in the glamorous hall at Brice-Petitjean. And then he remembered how he had come to be on his back. In the moment when he could have saved his great-aunt and become a hero, Archie had managed only to faint.

Was Penny dead?

“No!” he wailed. “Please, no!”

“No one’s dead yet,” said Angel, looming over him. “Though you just bumped yourself up to second in line. Any more heroes out there want to have a go?” he asked the room.

Oh, it was really too much. All his life all Archie had ever wanted was to be a hero, like the men and women who had served alongside his great-aunts in the war. Instead, he was on his back on the floor and that lunatic Angel was still waving his gun around. Penny and Josephine and Stéphane and all the other unfortunate hostages were still in danger. How had he got his attempt to defend Penny so horribly wrong?

Tears started to form in Archie’s eyes. He was useless to anyone now. He was pathetic. Pathetic. A long line of brave and magnificent ancestors stretched out behind him—war heroes, adventurers, pioneers all. Archie was the end of the line. Just as the terrifying dinosaurs had eventually evolved into chickens, in Archie the magnificent Williamsons had reached their nadir. No one would write books about Archie the Ignoble.

It was all so unfair. What’s more, he had brought this awful situation upon himself and his great-aunts. If he hadn’t been so keen to see Stéphane, if he could have played it cool, he would not have brought them here. Penny and Josephine could be back at The Maritime hotel now, sipping brandy and telling him stories about the times they’d spent in Paris as children, with their godparents Godfrey and Claudine. Instead, they were likely going to die in this room, and for what? Though Angel had expounded at length, Archie still didn’t really know what the siege was about. His French wasn’t good enough. What were they dying for? Likes on Facebook? Angel was carrying on again now, giving the people who might accede to his demands another five minutes in the light of the recent kerfuffle.

“Because I am a reasonable man,” he said in English this time. Reasonable? Someone needed to take his block off. There must be someone in the room who could do it. Where was Malcolm with his “capoeira” moves now?

“Don’t think, Archie, just act. Take the battle into the enemy’s camp.”

Archie could hear Auntie Penny in his head, explaining how she’d saved them from that mugger in New York. The man had waved a knife in her face as he demanded her handbag.

“Not bloody likely,” she’d said, jabbing the tip of her umbrella under his chin. She might as well have been kicking away an amorous Cockapoo for all the fear she showed.

And going further back, he remembered her writing on his plaster cast. “There are no rules. Only kill or be killed.”

“You can get that tattooed on your arm when you’re eighteen,” she’d said when she finished printing it in her very best handwriting.

“Why not suggest he gets ‘love’ and ‘hate’ tattooed on his fists while he’s at it,” said Josephine at the time. “Come here, Archie. Let me give you a cuddle.”

The sisters had given Archie so much. Without them, Archie knew his life would have been so much less interesting, so much less thrilling. They might have driven him crazy on occasion with their constant need for “excitements,” but he would not have changed a thing about all the wonderful times they’d spent together. He was not going to say his goodbyes from the parquet.

Closing his eyes, Archie did an inventory of his body. No part of him had really been hurt in the faint except his pride. His wrist ached but then it always did. He was bruised but not broken. Wasn’t that the “Invictus” line? No. Bloody, but unbowed. That was it. That was the line written on the matchbox in his pocket.

From his place on the floor, Archie did his best to work out exactly what was going on around him. Above him, Angel paced back and forth. He was right at the edge of the stage. All it would take was for someone to catch hold of his legs and pull him over, take the gun—he’d be bound to drop it in the fall—change the story. Finish him off with a punch to the jaw.

Take the battle into his camp. Act, Archie. Act. Kill or be killed.

Archie knew he could not just stand up and grab the man—well, not like he’d tried to do last time—but there was another way.

Archie took a deep breath. One, two, three ...

WATCHING THE CCTV footage in slow motion later, martial arts experts all over the world would hail Archie as a true master of the forgotten art of Defendu. Angel was too busy with his demands to notice Archie carefully shifting into position, laying out his right arm at ninety degrees to give himself leverage, turning his head to the left, tightening his stomach muscles, getting ready for the flip, raising his legs from the waist, and then shooting them over his shoulder.

When he executed the move, Archie moved so quickly from being prone to being on his feet that it seemed like a magic trick. He grabbed Angel around the knees, toppling him from the podium. Angel dropped his weapon and his phone just as Archie had expected him to, but he was still dangerous. Angel scrambled to get back up, eyes blazing hate. He pulled back his fist.

Luckily, Archie had another trick in his pocket ...

He had always wanted to try The Matchbox Defence, the move that W.E. Fairbairn warned could end in death. “Never practise this manoeuvre at full pressure,” the books said. “And certainly never practise it upon yourself.”

Kill or be killed.

With his hand around the matchbox, Archie smashed his fist into Angel’s cheek just as Angel’s fist made contact with the side of Archie’s face.

The matchbox gave Archie the advantage. He punched harder, stronger and in exactly the right place. It was a knockout blow. Angel crumbled.

Falling arse-first upon Angel in a move straight out of WWE, Archie moved fast to secure him, while he was still dizzy from the punch.

“I think we’ve had enough of this siege,” said Archie, tucking the matchbox back into his pocket.

ARCHIE’S BRAVERY GAVE gave others in the room confidence to move. The two other gunmen were taken down in an instant, without a shot being fired, just as the police finally, finally stormed in, using the unattended kitchen door.

Archie cried for someone else to take hold of Angel while he rushed to be with his great-aunts. Penny was still slumped in her chair, clutching the centre of her chest. Josephine was white with the excitement of it all.

“Hold on,” Archie instructed them both. “The paramedics are coming.

Toujours alive, please, Aunties. Toujours ...”

Josephine pushed herself up from her seat to go to her little sister. Her brave and crazy little sister.

“My Perfect Penny,” she cooed at her.

“Josie-Jo,” said Penny. “If this is the end, you know what to do.” Josephine nodded.

“This is not the end,” said Archie firmly.

He was right.

The denouement of the siege might have been utterly bloodless, but in the confusion that followed the arrival of the police, Dragomir Georgiev had grabbed the gun that skittered across the floor when Archie brought Angel down. Now Georgiev took aim at his accuser, his eyes narrowed with pure hatred as he pulled the trigger. And missed.

Missed his intended target, at least. Angel felt the shot fly right past him.

Josephine flew backwards, lifted from her tiny feet by the force of the bullet as it hit her in the chest.

Chapter Forty-Five

1940

“Well, you’ve got yourself into a right mess, Josie-Jo Williamson,” was the first thing Connie Shearer said when they were finally alone.

Josephine had known Connie Shearer for almost her whole life. They were born the same year, if in entirely different circumstances. Connie was the daughter of the cook at Grey Towers, home of Josephine’s paternal grandparents. When Christopher Williamson took his family to their ancestral home for high days and holidays, his daughters always rushed straight down to the enormous kitchen, to forage for biscuits and ask if little Connie could come out to play.

Between the ages of five and twelve, Josephine and Connie were on almost the exact same trajectory, but at fourteen, both girls donned new uniforms—Josephine for her smart new boarding school, St. Mary’s, and Connie for a kitchen maid’s role, following in her mother’s and her grandmother’s footsteps. After that, the girls were no longer encouraged to fraternize. Josephine was upstairs. Connie most definitely downstairs. In public, they were polite and distant but in secret, they still sought each other out and when Josephine arrived at the house in the January of 1940, Connie greeted her with a wink that said, “Hello, old pal.” At night, when the household was in bed, Connie crept into the room where Josephine had been billeted. It wasn’t Josephine’s usual room. She’d been banished to the servants’ floor this time. Her predicament was too obvious to risk her being seen about the formal rooms by her grandparents’ social peers.

“Come on. Tell me everything,” Connie said. “Who’s the father? And is he going to marry you?”

“I don’t think that’s going to happen,” said Josephine. She filled Connie in on the details.

Connie grimaced. “I’ll bet your dad isn’t happy.”

“He doesn’t know.”

Christopher Williamson had left for Salisbury with his regiment before Cecily caught a glimpse of her daughter’s belly straining her thin muslin nightdress and finally put two and two together. There followed three nights of long, anguished conversations about what should be done. They got as far as agreeing that Josephine should continue her pregnancy in Scotland, so as not to create gossip in the village. Neither should her father be told. Beyond that, Josephine still didn’t know what was supposed to happen when the baby eventually came.

“I expect your ma will pretend it’s hers,” Connie suggested. “Pass it off as your little brother or sister. Happens all the time.”

Josephine didn’t know whether she liked that idea or not.

The days ahead were miserable. Josephine’s paternal grandfather, who had once been so proud of her—“Always top of her form”—would not speak to her at all. He looked acutely distressed if they accidentally passed on the stairs. Her grandmother spoke only to express her disapproval.

“I don’t know what your parents were thinking, letting you go to Paris in the first place. And to stay with that drunken godfather of yours and his floozy of a wife. You were always going to get into trouble.”

It was easier to keep out of both her grandparents’ way.

Josephine had her meals in the kitchen. The staff—apart from Connie— were polite but reserved. When Josephine needed fresh air, she would shuffle around the family graveyard—the high walls held back the worst of the icy wind that swept down from the mountains—reading the names on the pets’ headstones. The highlight of her day was the moment the lights went out and Connie would creep into her room to talk.

Josephine knew that Connie was the only person in that house who didn’t judge her. She was also the only person in the house who gave Josephine any hint of what was to come as her pregnancy reached its final furlong. Though Doctor Muir visited every few days to make sure Josephine’s pregnancy was progressing as expected, he made it clear by his demeanour that he was not there to answer questions.

“I’m scared,” Josephine admitted to Connie, as the moment drew nearer.

“You mustn’t be. My sister’s been popping out one a year since she was our age. She has a bit of a lay down then she gets straight back to work, with the new baby hanging off her tit.”

Josephine winced.

“Oh lord. Sorry, Josie. I’m just trying to say it’ll be alright. If my sister can do it—and she makes a fuss about anything—then you can do it too. You’ll be alright.”

Connie folded Josephine into a hug, made slightly awkward by the expanse of Josephine’s belly.

“Will you stay with me when it happens?” Josephine asked.

“If I’m allowed,” said Connie. They both knew that was unlikely.

“DO YOU WANT to have children, Connie?” Josephine asked on another night.

Connie shook her head quickly. “No thanks. I’ve seen enough, looking after my nieces and nephews. Besides ...”

You Might Also Like

Meet ‘Excitements’ Author CJ Wray

This long-time romance writer was inspired to switch genres by real-life sisters still having adventures in their 90s

Free: James Patterson's Novella ‘Chase’

When a man falls to his death, it looks like a suicide, but Detective Bennett finds evidence suggesting otherwise

More Free Books Online

Check out our growing library of gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety

More Members Only Access

Enjoy special content just for AARP members, including full-length films and books, AARP Smart Guides, celebrity Q&As, quizzes, tutorials and classes

Recommended for You