AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Forty-Nine

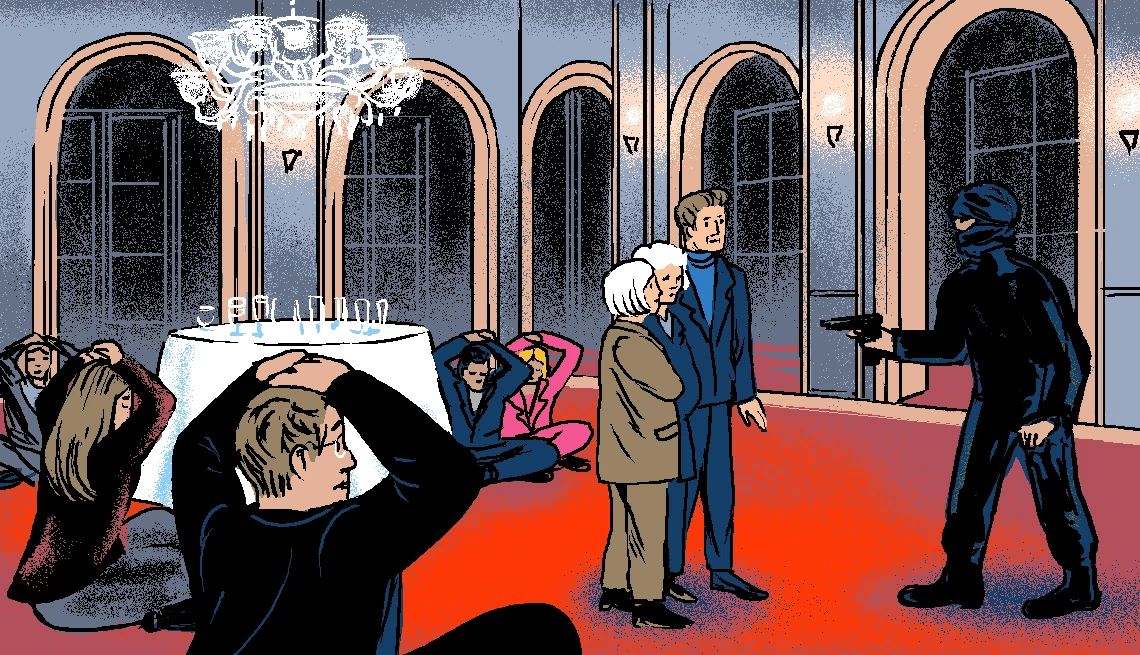

After a delicious lunch with Arlene, Davina, and Sister Eugenia, and an afternoon of television and radio interviews about the siege, Archie and Penny were relaxing in Penny’s hotel room when Josephine called.

“We ’ll both go to the hospital,” Archie said. He was eager to see these old letters, which he could imagine going into a book proposal. Having seen reportage of the siege on the internet, an acquaintance of Archie who worked as an editor had left three voicemails, eager to get a contract in place before another publisher swept in with a better offer.

LIMITED TIME OFFER: Labor Day Sale!

Join AARP for just $9 per year with a 5-year membership and get a FREE Gift!

In the taxi to see Josephine, Archie fielded emails. There was another one from Maddie Scott-Learmonth, with more information about her father. She’d attached a photograph this time. While Penny looked out of the taxi window at the Parisians going about their day-to-day, Archie surreptitiously compared Penny’s profile with that of Maddie’s father as a young man. There was definitely some similarity. That upturned nose. The interesting ears.

As if sensing Archie’s gaze upon her, Penny turned towards him. “Are you alright, dear?” she asked.

Archie had been wondering when to break the news to the sisters that perhaps there was a hidden branch to the Williamson family tree. Was now the moment? He nonchalantly informed Penny, “You know I sent off for a DNA test a short while ago ...”

“What inspired that particular madness?” Penny asked.

“I wanted to find out who my grandfather was.”

“But you know who he was. He was our little brother George. Oh, I do wish he was still around to have seen you be the hero last night. He would have been very proud.”

“Thank you, Auntie Penny. But I meant my other grandfather. There seems to be a question around my mother’s parentage.”

“Oh dear. That is unfortunate.”

“So I sent off for a DNA test and got back a notification telling me I’ve got a cousin in Canada. I thought that would solve the mystery of Mum’s roots but in fact it’s made things rather murkier. You see, there doesn’t seem to be a connection on my mother’s side at all. Instead this cousin says her father was adopted from Scotland in 1940. She says his mother was Connie Shearer. I’ve seen her grave at Grey Towers, haven’t I? Connie Shearer’s? She worked there, didn’t she? She died in the Blitz.”

“Yes. Driving an ambulance,” Penny remembered. “Poor girl.”

“But she was the cook’s daughter, at Grey Towers?”

“Yes, we used to play with her when we were children, whenever we were in Scotland for the holidays. She much preferred Josephine. They were closer in age. Connie used to pinch me black and blue. They both did. Though I suppose I did give them plenty of reason with all my tale-telling.”

“So she was at Grey Towers but why would anyone related to her be related to me? I mean, if she was the daughter of the cook and I’m definitely descended from the family. Unless perhaps ...”

Penny frowned. “Archie, what are you trying to say?”

“ARCHIE THINKS OUR grandfather had an illegitimate child with Connie Shearer,” was the first thing Penny said when they got to Josephine’s room. “He’s found some sort of cousin on DNA dot wotsit. Can you imagine, Josie-Jo? Have you ever heard such a thing?”

While Archie explained his theory and Penny continued to scoff at the very idea of it, Josephine held out the last envelope from 1940. Her hand was shaking in a way that they had never seen.

“Archie, I think that child might have been mine.”

IT MADE SENSE now—the note on the back of the letter. “He is not dead.” CS. Connie’s initials. And the postcard Connie sent when she got to London, telling Josephine, “I need to see you. There are things I have to tell you that I can’t put down in writing.”

This was what Connie had wanted to tell Josephine. She wanted to tell her that Ralph hadn’t died on that long-ago morning. Josephine hadn’t imagined the cry she heard from the courtyard. Ralph must have been taken away from the house on the day of his birth, presented to the registrar by the GP as Connie Shearer’s child—Connie’s reputation, as a housemaid, being considered less valuable—then adopted by a respectable local couple who were about to move to Nova Scotia.

“They told me they’d buried him in the pets’ garden,” Josephine told her astonished sister and great-nephew. “Next to Zephyr.”

Zephyr was their grandfather’s favourite dog. The German shepherd that had bitten all the Williamson children at least twice.

Seeing the horror on Archie’s face, Josephine rushed to comfort him. “They loved their pets more than most humans so it’s not the demotion you think.”

Penny had to agree.

“But to tell you that.” For once Archie was of a more modern view. “I can’t believe it. It’s horrific.”

“It was a different time. And I’d rather concentrate on the fact that I think at last I know the truth thanks to you, our dear family historian. But is he? Is he?”

Josephine couldn’t finish the sentence.

“Alive now? Yes, Auntie Josephine. Yes, he is.”

Chapter Fifty

“Is there a term for feeling as though one might explode from happiness?” Josephine asked her sister. “Because that is how I’m feeling right now.”

“The Germans must have a word for it,” said Penny. “We’ll have to ask Archie to google it when he comes back.”

Archie was outside the hospital, making calls to his gallery in London, leaving the sisters alone with each other for the first time in quite a while.

“My son has been alive all these years,” Josephine said in a tone of wonder.

“Bloody amazing, isn’t it?” said Penny.

“That’s an understatement.” Josephine sniffed back a tear. “You know, the funny thing is, I think I always knew. They told me he was dead and that was the story I told myself, but deep down there was always a part of me that never quite believed it. You remember when we went to Paris in ’47 and Gilbert told us about August?”

Penny nodded. “How could I forget?”

“I could feel it ... I could feel that he was gone the moment I heard the words. But it was never like that for my baby. No matter how many years passed, I could still feel his presence. Though logic told me I was being ridiculous—why would our grandmother have lied about his dying—I looked out for him everywhere. I would see a little boy in a playground, with August’s thick brown hair, and my heart would leap out of my chest. I was so certain I would see him. Every year on his birthday, I felt him so strongly, Penny. So strongly. I would find a place to be alone and sing ‘Happy Birthday’ as loudly as I could so that he could hear me wherever he might be. And then I would push my love out across the universe so that it would get to him and wrap around him and let him know that I never stopped thinking about him or loving him for a single second. My head said he was gone but my heart—never! And now he’s back and I can tell him in real life.”

She pressed her fingers to her eyes to stop the tears from rushing in again. It was a hopeless exercise. Even Penny’s nose was pink with the effort of keeping her own tears back.

“He’s still alive.”

When Josephine opened her eyes again, she picked up the printout Archie had asked the hospital receptionist to make of the photograph his new cousin had sent him. The moment Josephine saw that picture, she knew that this was her child. There was no doubting it.

“Look at this face,” she said to Penny, for the twentieth time. “How could he not be mine?”

He had the Williamson nose. He had August’s eyes. He had the same widow’s peak as dear Archie.

“He’s got all our family’s best bits,” Penny agreed.

“He’s perfect,” said Josephine. “He’s my boy.”

Josephine would be talking to her son later that evening, as soon as Madeleine Scott-Learmonth got to his house and helped him make a Zoom call on her laptop.

“What am I going to say?” Josephine asked her sister. “So many years of sadness. I can’t believe they’re coming to an end at last. Do you think he’ll forgive me?”

“What is there to forgive, Josie-Jo? You were lied to.”

Josephine’s hands trembled as she lifted the photograph to her face and kissed it.

“My son. My darling son.” She held the photograph towards Penny and chuckled. “Your nephew.”

Penny pressed the heels of her hands to her eyes. “Stop it. You’re making me cry.” When she dared to look at her new nephew’s face again, Penny said, “There’s something of George about him too,” remembering the little brother they both still missed so much. “Thank goodness Archie put aside his horror of spitting to do that DNA test.”

“Thank goodness.”

Josephine pressed the picture to her chest. The thought of how lucky she’d been that Archie was such a genealogy nut was dizzying.

“Can I be here when you take the call from Canada?” Penny asked.

“I want you right beside me.” Josephine reached for Penny’s hand. “Ralph needs to know what sort of family he’s getting into, warts and all.”

“I promise not to be a bad influence.”

“Only he’s not called Ralph now, is he? He’s Edgar. That’s going to take some getting used to.”

“Edgar is a good solid name,” said Penny. “Yes,” Josephine agreed. “It is. Edgar. My boy.”

“My nephew.” Penny tried out the word for size.

“My son,” said Josephine. Then once more with emphasis. “My son.”

Chapter Fifty-One

“We have a lot to talk about, you and I,” said Penny, a little later. “I can’t believe you didn’t tell me you had a baby. I might have helped you. Why didn’t you trust me enough to say?”

“I think I thought you might have guessed, but when you didn’t ever ask ...”

“You could have told me. If not then, at least at some point in the last eighty years. I’ve never kept anything from you. Not a thing.”

Josephine snorted.

“I haven’t!” Penny insisted.

“Then tell me, what exactly did you mean when you tapped out in Morse last night that you’d swallowed a ring?”

“Did I say that? I must have got my code wrong.”

“You said it.” Josephine cocked her head. “Well? Has it worked its way back out into the world yet? That’s why you asked the nurse for laxatives, yes? So what ring? And where did you find it?”

“Oh, it was a mistake.”

“Penny, I think this is the moment for truth.”

It came out in a rush. “I thought the ring that Veronique Declerc had for sale in the auction was the ring that August showed us all those years ago. The one he said belonged to the Russian Duchess. I thought it because I told Gilbert about the safe hidden beneath the Samuel family’s bathroom floor and I was certain he told his mother after Leah and Lily were taken away. How else to explain the Declercs’ sudden change in fortune? So I decided to steal it back. I asked to try it on and swapped it for a toy ring I had that looked a bit like it.”

Penny shrugged as though what she was saying was quite reasonable.

Quite commonplace.

“Goodness knows what I thought I would do with it,” she concluded. “Same as you did with all the others?” Josephine suggested.

You Might Also Like

Meet ‘Excitements’ Author CJ Wray

This long-time romance writer was inspired to switch genres by real-life sisters still having adventures in their 90s

Free: James Patterson's Novella ‘Chase’

When a man falls to his death, it looks like a suicide, but Detective Bennett finds evidence suggesting otherwise

More Free Books Online

Check out our growing library of gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety

More Members Only Access

Enjoy special content just for AARP members, including full-length films and books, AARP Smart Guides, celebrity Q&As, quizzes, tutorials and classes

Recommended for You