Jeff Daniels on the Greatest Challenge of His Career

In 'To Kill a Mockingbird,' he has crafted an Atticus Finch who speaks to a modern audience

- |

- Photos

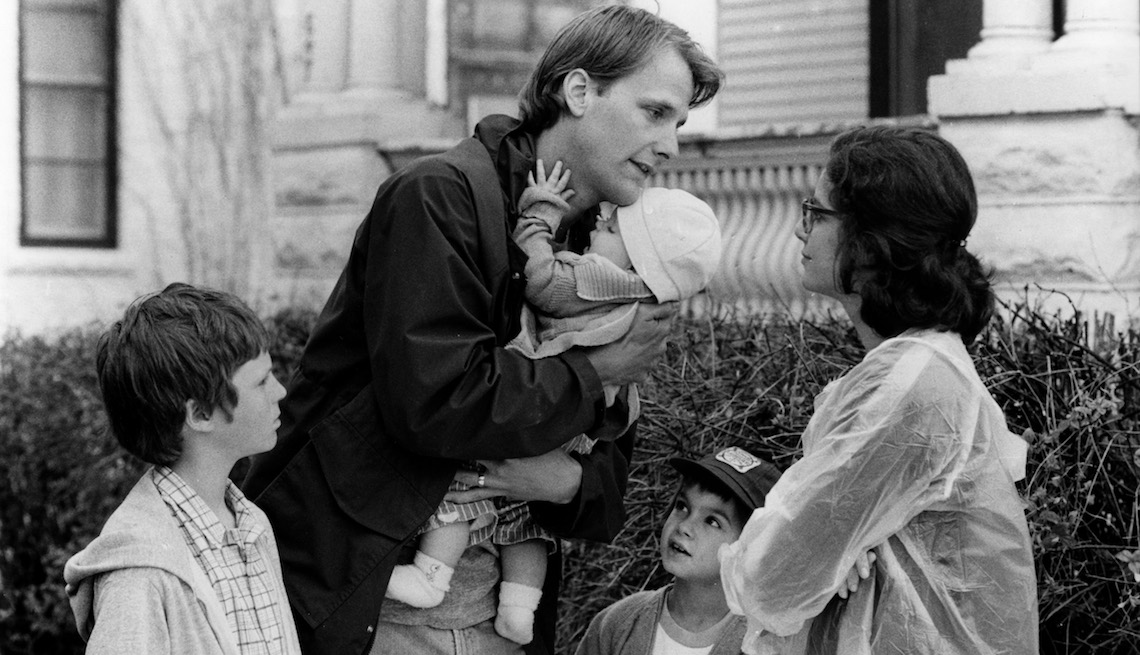

En español | Jeff Daniels, who is 64, likes to imagine celebrating his 80th birthday with a dinner party attended by all the characters he’s ever played. So far, the guest list is nearly 90 names long, including Will McAvoy, the arrogant anchor from the HBO series The Newsroom; Flap Horton, the spineless husband from Terms of Endearment; and the sublimely imbecilic Harry Dunne from Dumb and Dumber. The most prominent figure on the list, however, and likely still to be so in 16 years, is Atticus Finch, the saintly protagonist of To Kill a Mockingbird, whom Daniels plays currently on Broadway. Atticus, as he is known even to his children, is significant in an unusual way, says Daniels: “He is a fictional hero so iconic that some people think he’s real.”

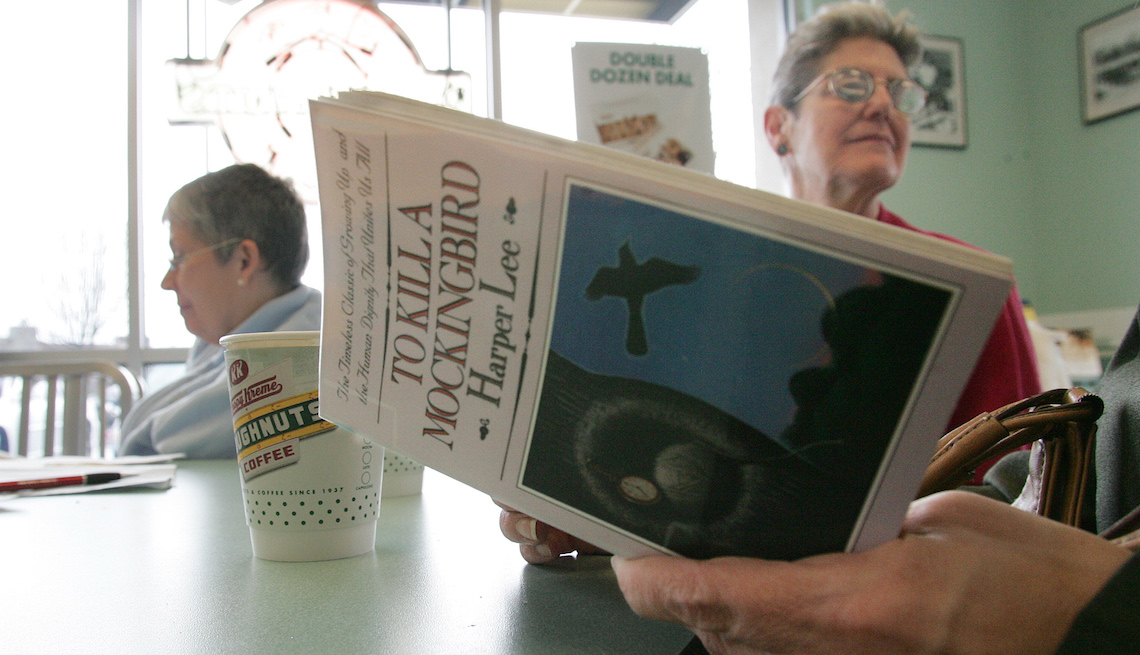

To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee, is as close to ubiquitous as a novel is likely to get. Set in the imaginary town of Maycomb, Alabama, in the 1930s, it was published in 1960 and has never been out of print. In 1962 the book was made into a movie starring Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch—a movie that has never been remade.

Peck’s portrayal of the idealistic, brooding attorney established the character so effectively that generations of Americans tend to picture his face when they think of Atticus. Peck’s height and his upright, laconic manner subtly suggest a young Abraham Lincoln in a small-town courtroom, lawyering for truth.

Lee embraced the portrayal. Although she authorized a stage adaptation of her novel in 1969, that version was only for schools and community theaters. She refused to approve it for the professional stage. As she explained to Peck in a letter in the 1980s, “I’ve refused scores of requests from some mightily talented people to turn M’bird into everything from a Broadway play to an opera. I have always said no for one reason: I cannot run the risk of having your Atticus diminished in public memory by so much as a scintilla.”

Not long before Lee died, however, in 2016, she agreed to sell the stage rights to the Broadway producer Scott Rudin, who hired Aaron Sorkin to write the script. Sorkin, who is known for terse dialogue, wrote the screenplays for A Few Good Men and The Social Network, and he was also the creator of TV’s The West Wing and The Newsroom. He asked Daniels if he would care to play Atticus, and Daniels agreed. “I’ve never been one to start weeping at a moment like that,” the actor said recently. “So I said, ‘Should I read the book?’ It was my way of saying, ‘I need to hear you say that again.’ ”

Watch: Jeff Daniels on Reviving 'To Kill a Mockingbird'

A version of Atticus for the 21st century would need to be more complex than the one Peck portrayed. The Lee estate had insisted that Sorkin’s Atticus would not drink or take the Lord’s name in vain, but the new play’s hero is less monochromatically honorable than the one in the 1962 film, and more sensitive to the feelings of others, especially his black housekeeper, Calpurnia. Whereas Peck’s Atticus was naive about whether a jury would reach a just verdict, Daniels’ version is skeptical.

Daniels knew the enduring impression that Peck’s Atticus had made but felt he needed to construct his own version of the character. “You can’t go out there thinking, Peck did this, I’m going to do this,” Daniels said. “I’ve seen actors have to deal with signature roles, and sometimes they choose to do exactly the opposite of the original, and I’m not sure that works.” While he talked, Daniels sat at a table beside a window in a cafe in New York City. It was the middle of the morning. He is a tall, sturdily built man with the mild, unassuming look of someone who might be a Little League coach admired for his commitment to fair play.

The actor grew up in Chelsea, Michigan, about 40 miles west of Detroit, where his father, Bob, owned a lumber company and for a while was the mayor. Daniels went to Central Michigan University until 1976, his junior year, when he moved to New York to be an actor. In 1979 he married Kathleen Treado, who was also from Chelsea, and in 1986, they moved back home to raise three children; he continued to work in New York and found success in Hollywood, too. Daniels has won several Tony and Emmy awards, and been nominated for four Golden Globe Awards. He started the Purple Rose Theatre Company in Chelsea and is an accomplished guitar player, singer and songwriter.

Daniels spent a summer memorizing the script for Mockingbird. Actors don’t usually arrive at first rehearsals with the script memorized, but Daniels did, because “the profile of this thing was so big that I wanted to be prepared.” Whatever anxiety he felt about appearing in Peck’s shadow, he overcame by doing what his upbringing had trained him to do. “If you want to combat nerves, be more prepared,” he said. “It’s the Midwestern work ethic.”

To play Atticus, Daniels also studied the history of Southern towns. He read Go Set a Watchman, the novel Lee wrote before Mockingbird and which was controversial when it was finally published in 2015, because its Atticus is a far less sympathetic figure. In addition, he read biographies of Harper Lee and watched videos of Frank Johnson, a legendary federal judge in Alabama whose rulings in the 1950s and 1960s helped end legal segregation. “He put KKK guys in jail when it was easier not to,” Daniels said. “He also had a great accent to model my own on. So a year ago, I was walking around the lake speaking like Frank Johnson.” Daniels paused, then said drowsily, “ ‘A registered cawt of laaaaw.’ ”

A Book for Our Time

It’s one of our nation’s most revered texts—and it’s probably the book that has most shaped our collective understanding of the evils of Jim Crow. With sales of more than 40 million copies since its publication in 1960, Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird appears frequently on surveys as one of the most important books in Americans’ lives. It’s a high school English staple—the book that’s most assigned to ninth and 10th graders, according to one 2012 survey. The novel is “secular scripture,” argues Harper Lee scholar Casey Cep. “It’s one of only a handful of texts most Americans have in common.”

Mockingbird first appeared in a tumultuous era, when African Americans were organizing to demand desegregation and equal rights. And the story’s rebirth on the Broadway stage at the end of last year arrives at another fractious time—a time when a new Mockingbird for a new age feels like just the thing we need.

As Mockingbird begins, Atticus is appointed to defend Tom Robinson, an African American man accused of rape by Mayella Ewell, a young white woman who lives with her violent, alcoholic father and seven siblings in a shack by the town dump. Robinson has helped Ewell with chores in the past, but he did not attack her, which Atticus demonstrates conclusively in court. Robinson is doomed, though, when he says he helped Ewell because he felt sorry for her. Pity for a white woman by a black man, however lowly or forlorn the woman’s circumstances, was forbidden by consensus in Alabama in the 1930s. The jury finds Robinson guilty, and Atticus is left deeply shaken.

While Peck’s Atticus represents virtues that are timeless, he is perhaps too simplistic to be a modern figure, just as “I Want to Hold Your Hand” is too simple to be a modern love song. His Atticus is modest, fierce, brilliant, austere and self-contained. Though people need him, he doesn’t need other people. Daniels’ version has a broader range of feeling and a decided warmth. Peck’s morality is stern, and Daniels’ is benevolent. Peck’s version is wounded by his having lost his wife to a heart attack, but he can’t express the full extent of his emotions, whereas Daniels’ version is passionate. Plus, Daniels has a deft comic touch, especially in dealing with children, whereas Peck’s Atticus has the remoteness of a lighthouse.

Peck’s portrayal is, in addition, from the era when American movie heroes were tight-lipped white men thrown into conflict by the force of their beliefs, men who met danger courageously and hoped to persuade by their example. Such heroes were aspirational as much as realistic. Daniels’ Atticus, by contrast, seems to be shadowed by the awareness that doing all he can might not be enough. Along with the rest of us, he seems to share the modern awareness that life is possibly too complex, and too many interests are at stake, for a single moral stance to answer all situations.

“It’s not 100 percent he’s going to lose, but I’m going up a steep hill as I start the closing argument. You have to convince a jury of white farmers about the innocence of a black man in Alabama in 1935."

For entertainment news, advice and more, get AARP’s monthly Lifestyle newsletter.

As we talked, a waitress brought Daniels more coffee. Speaking of his preparation, he said, “You let it all cascade over you. You think, What do you need to do to feel like you’re inhabiting him? In the end, what I wanted was to see what Atticus saw when he stood on his porch.”

“Does your version draw on anyone you know?” I asked.

“My dad was very much an Atticus, in that there was a right way to do something and there were all the other ways,” he said. “He lived like that.”

Creating a convincing Atticus also involves the trick of living within him as the play unfolds. “As Atticus,” I asked, “do you know if Tom Robinson is going to lose?”

“It’s not 100 percent he’s going to lose, but I’m going up a steep hill as I start the closing argument,” Daniels said. “You have to convince a jury of white farmers about the innocence of a black man in Alabama in 1935. They are all sitting there with their arms folded and staring at you. You’re swimming upstream. You’re getting more and more frustrated. You keep looking to the jury box, and you finish angry. Angry at Tom for making his mistake. Angry at the judge for giving you this task, angry at losing.”

Daniels looked out the window at a woman pushing a stroller. “Atticus believes in the law,” he went on. “He can’t believe that there are people who do what these people, his neighbors, are about to do in finding Tom guilty.”

He paused to consider a thought. “Here’s the other thing about all of this,” he said next. “I’m working harder than in any decade of my life, which is not how they draw it up in star school. Acting is craft, and when you get roles like I’ve had lately, you need everything you’ve ever learned to pull them off. I find myself using things I learned years ago. I tell drama kids, ‘Find out what you want to do and spend the rest of your life getting better at it,’ and that still is the case, I find, at 64.”

Another benefit of extravagant preparation is that it has given his performance a freedom it wouldn’t otherwise have had. “Since you know your part cold, you’re able to follow the impulse that just occurred to you,” he said. “The art and craft comes from not chasing impulses that are inappropriate or wrong or ruin the scene. You learn how to make the choice. The only way you can get there, though, is time. A long career. I didn’t think it would be like that. It’s pretty cool, being in the moment, enjoying every moment. Perhaps that’s too Pollyanna. But I find myself not in such a hurry to be done with what I’m doing.

“Besides,” he said, as the waitress cleared the table, “being Atticus is a pretty good way to spend the night.”