By David Hochman

Part I: A Bag of Money

IN APRIL 2018, a video appeared on YouTube that changed everything. It was recorded on a cellphone at the Silicon Valley Comic Con, a comic book convention where Stan Lee was a star attraction. In the grainy video, the 95-year-old creator of Marvel Comics’ Spider-Man, Hulk, Black Panther, X-Men and others appears unable to sign his name. Which is important to note, because Lee and his handlers were there to sell his signature for $120 a pop. A dark-haired man in his 40s, dressed like an MTV gangster, in a black skinny suit, black fedora and sunglasses, coached the barely cognizant writer through the task.

The man, later identified as Lee’s former business associate Keya Morgan, spoke to Lee as if he were a child, schooling him on how to spell his name. “Stan Lee. S-T-A-N …” Morgan spelled it out again and again as comic book after comic book was slipped in front of the white-haired Lee.

In the video, Lee looks unsteady, propped up in a chair, while a line of fans snakes out of the frame, each waiting for a chance to meet their hero. Though only 58 seconds long, the video is painful to watch. In the dark humor of the internet, it came to be known as “Weekend at Stan’s,” after the 1980s cult-comedy film Weekend at Bernie’s, in which two low-level insurance guys drag their dead boss’s body around to persuade his friends he is still alive. Fans who observed this tragedy took to the event’s Facebook page in outrage. “That man is a legend and you shuffled him around like he was a bag of money!” one wrote.

A few days after the video was posted, the Hollywood Reporter published a detailed article documenting years of questionable activity around Lee, accusing his advisers of taking over his management and finances and using the aging icon to enrich themselves — while showing little concern for Lee’s physical or mental well-being.

Reports of his abuse had been slowly gathering since the death of his beloved wife, Joanie, in 2017. Strong-willed and outspoken, the British-born former model had run the Stan Lee family business with a firm hand. She had monitored her husband’s bank accounts and tracked his appearances more carefully than Lee himself ever cared to.

She had also been more adept at managing their mercurial daughter, Joan Celia Lee, called J.C., which is likewise important to note, because J.C., 70, will become a player in this sad tale of (alleged) elder abuse.

But in the spring of 2018, Joanie was gone, the shocking Comic Con video was being seen hundreds of thousands of times, and a welter of accusations suddenly spilled into the public arena: There was talk of millions looted from Lee’s bank accounts, his property scavenged, his physical condition deteriorating — in full view of his legion of fans.

How could this be?

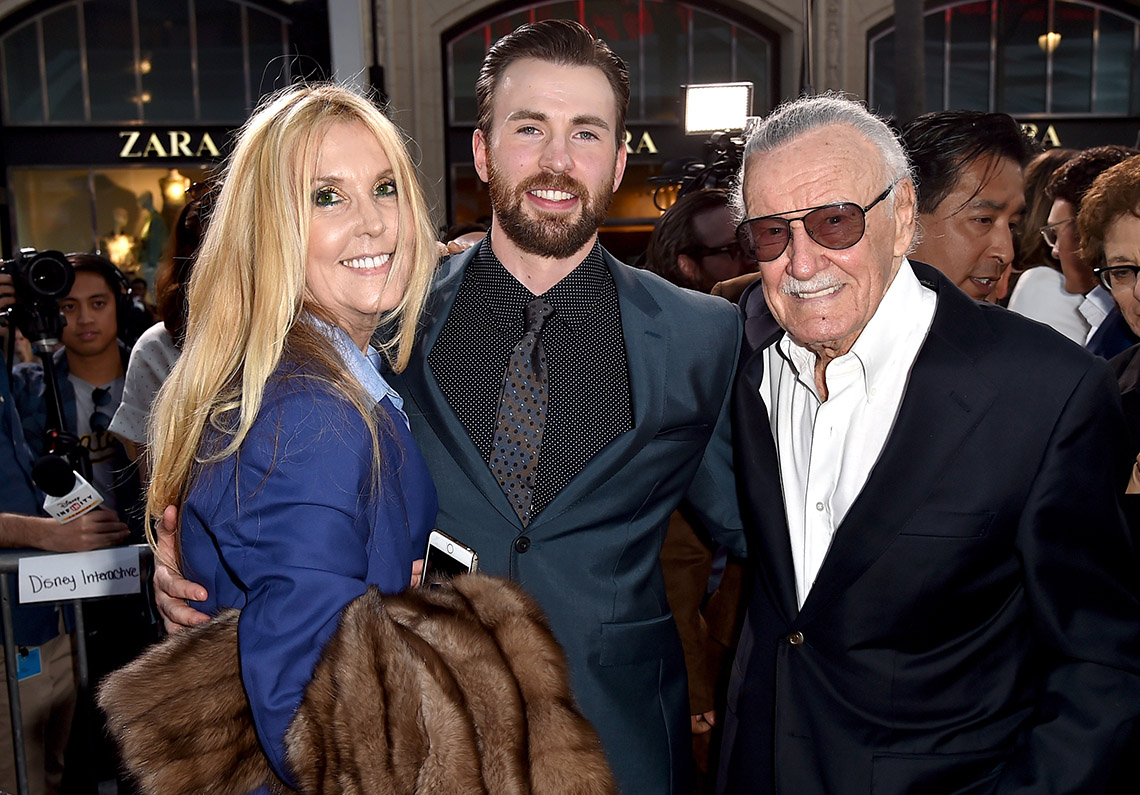

It’s difficult to overestimate this man’s influence on American pop culture. Films based on Lee’s Marvel characters have grossed more than $22 billion worldwide, more than double the ticket sales of all the Star Wars movies combined. Lee was credited as a producer for many of these blockbusters, but what drew cheers were his acting turns in 39 of them. He was a crackerjack bit player, appearing on-screen for five seconds or less (Vanity Fair noted that Lee might have surpassed Alfred Hitchcock as the most recognizable cameo actor in Hollywood) and usually dropping a droll line with a wink and a grin. Fans (when he died, he had 3.5 million Twitter followers) couldn’t wait to point him out as he popped up. Hey! Look! It’s Mr. Marvel himself!

After Stan Lee died on November 12, 2018, in Los Angeles, former Beatle Paul McCartney said he counted himself “lucky enough to meet him.” Billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk remarked that Lee’s contributions to humanity “will last forever.” A few months earlier, Game of Thrones author George R. R. Martin had placed Lee “right up there with Walt Disney as one of the great creators of characters — probably bigger.”

As we approach the second anniversary of Lee’s death, a half-dozen civil suits are pending and a criminal elder-abuse prosecution by the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s office remains mired in pretrial maneuverings. The courts have yet to shed light on many of the details and the veracity of the elder-abuse charges against several people. Elder-abuse cases are difficult to bring to trial, tough to litigate and hard to win. Was Stan Lee, like 1 in 10 Americans over age 60, a true victim of elder abuse, which can include physical violence, emotional torment, financial exploitation and willful deprivation? Plenty of evidence and testimony suggests that may be true.

But uncomfortable questions will arise along the way: Is it possible that our real-life hero, like many others in his situation, was complicit in his own abuse? And who will be the villain in this story? There will be plenty of suspects to choose from, but in the end, you will be shocked but not surprised.

Part II: An Irresistible Temptation

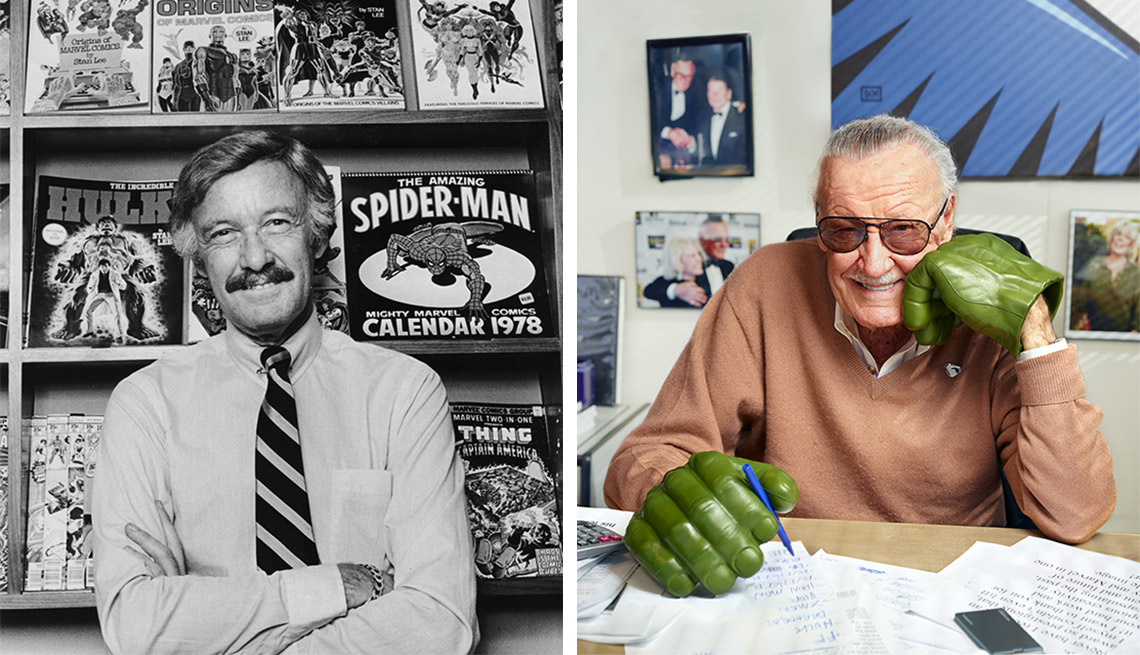

IT WAS ALWAYS about the cash. From childhood, Stanley Martin Lieber learned how to hustle. Lee recalled that his immigrant parents quarreled incessantly — “almost always over money or the lack of it.” As a teenager in New York City, he sold newspapers, delivered sandwiches and worked as a movie usher. After high school he wanted to go into acting or law or write the great American novel. But fate intervened when young Stan was offered an $8-a-week assistant job at a Manhattan publishing firm owned by his cousin Martin Goodman. In 1939, Goodman started a comic book imprint called Timely. Timely launched Marvel Comics #1, and Lee’s destiny was set. He would work for Marvel for the next 75 years.

Cranking out adventures and pulp crime dramas at a dollar a page, Lee was so prolific that he adopted pseudonyms — such as S.T. Anley and Neel Nats (spell it backward) — to make it look as if the publisher had hired a battalion of writers. Lee soon rose to be editorial director at the brand-new Timely offices in the Empire State Building, as titles featuring Captain America, the Sub-Mariner and the Human Torch got snapped up by the millions in the comic book boom of postwar America.

But it turns out Lee’s appetite for work overshadowed his desire to learn the ropes of financial security. Though I followed his career for decades and interviewed him at length on several occasions, I was shocked (and still am) to learn he’d never held the rights to his stories. Marvel owned everything and always would. Another surprise: Lee couldn’t draw. His visual collaborators, such as Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, created the look and feel of each character and panel — setting up lifelong beefs around who deserved more credit. But none of them considered comic books consequential. In those early days, explains Michael Uslan, the producer of the Batman movies and a lifelong friend of Lee’s, “once a comic book was engraved and went to the printer, nobody thought it meant anything. They used their work to put their coffee on, to smudge out their cigars on.”

As Lee told me in one of our interviews, “You have to understand that growing up during the Depression, I saw my parents struggling to pay the rent. I was happy enough to get a nice paycheck and be treated well.”

Even as he built his version of the American dream — Stan and Joanie married in 1947, daughter J.C. arrived in 1950, and they lived comfortably on suburban Long Island — Lee never had to take his finances seriously. “Things were almost too easy for me,” he wrote in his 2002 autobiography, Excelsior! “If Joanie wanted a new wardrobe or I wanted to get a new TV, I’d say, ‘Well, I’ll write a couple extra stories.’ ”

Those stories and Lee’s breakthrough characters in the 1960s, particularly Spider-Man, changed the comic universe. Nobody had ever encountered, as Lee put it, “superheroes with hang-ups” before. People talked about these conflicted protagonists in the same breath as they spoke of women’s lib, 007 and NASA.

The ’70s, ’80s and ’90s weren’t as generous. While Lee made a very nice living, he slipped ever further from ownership positions, even as comic books spawned blockbuster movies. The massive payday that seemed his due eluded him. When Disney acquired Marvel in 2009 for $4 billion, Lee continued to receive a relatively modest annual salary that never included a stake in Marvel movies or TV shows. After Lee moved to California as a Marvel ambassador in 1980, his personal efforts in movies and TV mostly fell flat, and studio executives kept him at arm’s length on his own creations. His title “executive producer” on films such as The Avengers was mainly to keep loyal Marvel superfans from storming the studio gates.

IN THE LIFE CYCLE of Hollywood fame, there often comes a time when looks fade and opportunities diminish but the thirst for adulation — and the need to pay bills — does not. So, many an aging star begins a descent into the demimonde of live appearances, conventions, autograph signings, memorabilia shows, endorsements and the like, all of which can generate quick, easy cash — “garbage bags full of 20s,” as the Hollywood Reporter put it. It’s a world that has welcomed the likes of O. J. Simpson, Mr. T, Mark Hamill and the casts of dozens of beloved TV shows, most prominently Star Trek — though the needy fans nearly drove William Shatner insane.

The massive fan gatherings known as Comic Cons turned 50 last year. And they have remained, at least before COVID-19, an exuberant celebration of geek culture that draws 130,000 or more fans to larger venues. By the time Lee reached his 80s, his income revolved around constant appearances, from San Diego to Tokyo to Abu Dhabi. A weekend’s take could land as much as a book or movie deal. But between travel, scheduling, logistics and demanding superfans, it is grueling work that required Lee to take on help.

All was well for a while. This new second career generated piles of money for Lee and his growing circle of advisers, and satisfied the writer’s hunger for love and attention. But the Wild West nature of the business set him up for exploitation. As Paul Greenwood, a California prosecutor with experience in more than 600 felony cases of elder and dependent-adult abuse, told me, “Cons can smell opportunity a mile away.”

The very qualities that industrious people of Lee’s generation pride themselves on — working hard, trusting people, showing respect for authority, raising children to be better off — were traits that did not serve him well as he grew more vulnerable with age. On top of that, Lee didn’t like banks and was thought to be stockpiling cash at home, an irresistible temptation for unscrupulous employees.

And then there’s J.C., his daughter, never married, who tangled herself up financially and emotionally with a trio of men who had shady pasts and were later accused of chiseling away at a family fortune estimated to be worth between $50 million and $70 million. Stan and Joanie had always worried about J.C.’s stability. She couldn’t hold a job. She spent too much. They created a trust, fearing she would blow through an inheritance and end up living in her car.

“When J.C. and I disagree — which is often — she typically yells and screams at me, and cries hysterically if I do not capitulate.”

J.C.’s involvement in her father’s affairs likely explains why things stayed hushed up for so long. People of Lee’s generation are “very private,” said Renee Rose, deputy-in-charge of the Elder and Dependent Adult Abuse Section of the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s office, which is prosecuting one of the criminal cases involving Lee’s estate (though Rose herself is not involved in the case). “They don’t air their dirty laundry.”

Part III: The Protectors

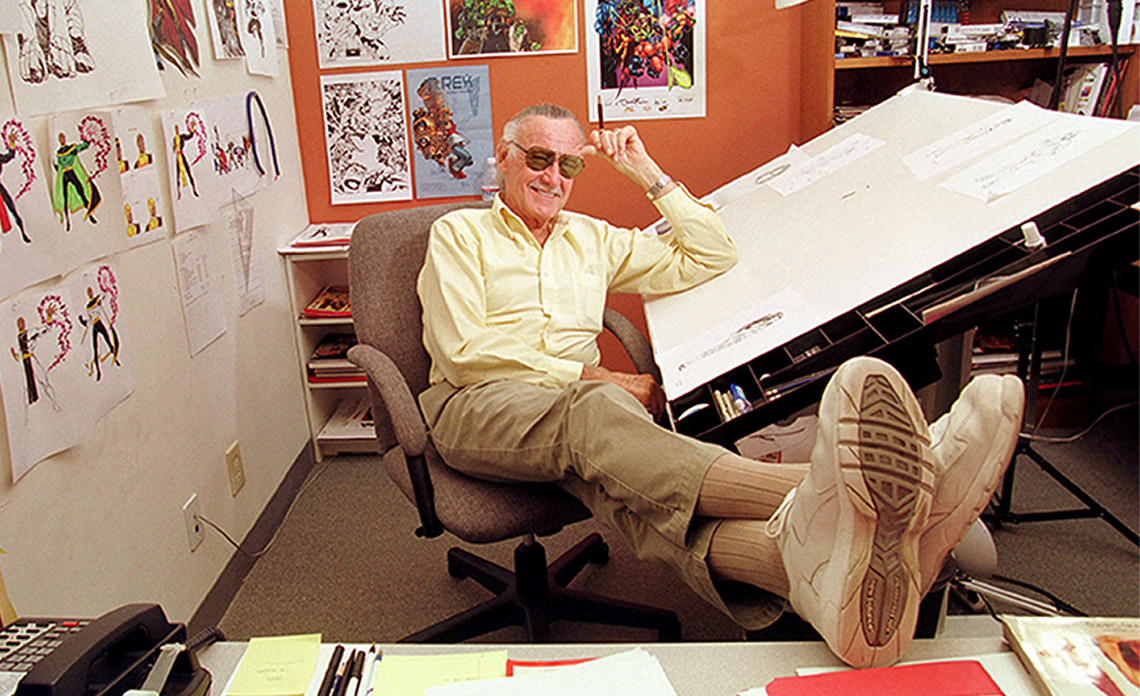

I FIRST MET STAN LEE around 2008. He was 85, and brimming with vitality. Physically wiry, he was a quick-witted fast talker in aviator shades and that famous lampshade mustache. When I asked him why he continued working long days and weekends, I thought he might hit me with a Thor hammer.

“I never want to retire!” he announced with his sandpaper delivery. “It’s fun doing what I do!” And clearly it was. His office was filled with framed photos of him with Hollywood stars and world leaders. (“Reagan, I heard, would wake up in the morning, and the first thing he would do is read the Spider-Man comic strip,” he let me know proudly.) Stan Lee even had his own action figure and boasted about upcoming film and publishing projects. “I’m doing something now with God as a theme, and it will be a big production,” he said, waiting for my laugh.

Between the time I met him in 2008 and his death in 2018, three newcomers inserted themselves into Stan Lee’s life, befriending him and his daughter and offering support, counsel and business ideas, but ultimately enriching themselves through their connection — legally or not, we will try to learn. These three have since turned on one another, laying out the alleged abuses and misdeeds of their rivals (while trying to absolve themselves) in civil and criminal cases pending in Los Angeles County Court. They all accuse each other of stealing from the man they loved and idolized.

I set out to talk to each of them to get their side of the story.

The first was Max Anderson, a blustery, burly security guy who plied his trade at comic book events. In 2006, Anderson was assigned to coordinate Lee’s schedule and help him navigate “the floor” at San Diego Comic-Con, with its 100,000-plus Marvel-mad attendees. Lee and Anderson, both chatty, salt-of-the-earth types, became fast friends, and by 2007, Anderson was working with Lee’s team to book and coordinate appearances at various events and monitor all the paydays.

If Lee had been a little less trusting, he might have turned up Anderson’s 2002 felony conviction for beating up his wife, for which he spent a year in jail. Anderson would be found guilty again in 2010, for hitting his son with a belt and slamming him on the floor. For that, Anderson received three years probation, a fine and orders to complete anger-management and parenting classes. It appears that Lee, his family and his team of lawyers, managers, agents and others never took note of that history.

By 2010, Lee was “becoming, or had already become, completely dependent” on Anderson for many of his commercial endeavors, according to a lawsuit filed by J.C. Two sources who worked inside Lee’s circle (who asked to remain anonymous, for fear of legal and physical retribution) estimate that Anderson walked off with at least $8 million in cash and memorabilia from Lee

Anderson insists every penny and collectible was a gift from Stan and Joanie. He recalled for me the day they first turned over their personal mementos to him for a Stan Lee traveling museum: “Joanie goes, ‘Come here, dear,’ and grabbed my hand. We walked over to one of the rooms, and she opens the door and she goes, ‘I want you to have this’ — pointing to keys to the city, proclamations and the like. I’m, like, ‘Holy smokes. No, I can’t.’ She goes, ‘We want you to.’ Stan says, ‘We want you to.’ ” Anderson’s eyes well with tears as he tells me this.

By 2012, with the first Avengers movie packing theaters and Lee’s characters making it to network TV, Marvel’s cofounder entered his 10th decade with a Sharpie practically affixed to his signing hand. Comic book dealer Chandler Rice, who coordinated signings with Lee and Anderson during those years, estimates that Lee was now autographing a thousand items at each outing. Fans paid $80 for each signed comic book, with Lee’s team taking a $40 cut. At the end of each event, “basically what would be handed to Max would be about $40,000, and by 2014, we had to pay him in cash,” says Rice, whom Anderson cut out of the business later that year. J.C.’s lawsuit asserts that “Anderson collected more than $800,000 in cash and goods related to Lee’s appearance at New York Comic Con in November 2017 and paid himself $700,000 as a management fee while giving Lee only $50,000.” Meanwhile, the older man was left “worn out and complaining he could not go on.”

The case is pending, mired in a pandemic backlog of court delays. In the midst of these signing marathons, I spent several days with Lee for a long Q&A for Playboy in 2014. He was 91, and I had to yell to make myself heard. He looked tired and griped about his pacemaker and macular degeneration. But he still went to work five days a week, insisted that life with Joanie was peachy and swore he couldn’t wait to get to the next speaking engagement or convention. “Even if I’ve heard the question 800 times before, I always try to give an answer people don’t expect,” he said. “Like ‘What superpower would you want?’ I say, ‘Luck,’ because if you have that, you have everything.”

That luck was running out.

The second man in question, Jerardo “Jerry” Olivarez, first encountered Lee at an Iron Man 2 red-carpet event in 2010, where he was doing publicity for a theater chain. They hit it off, and Lee soon hired Olivarez to work with J.C., in hopes that he could help her find some direction in a show business career. Despite his fancy title of senior adviser, the diminutive, loquacious Olivarez was mostly a high-priced babysitter. He collected $7,000 a month, one source told me, to accompany J.C. on shopping trips and help her brainstorm projects that might capitalize on her father’s name.

Lee apparently never checked Olivarez’s background either, which showed 45 liens filed against him for failure to pay federal, state, city and county taxes, as well as 15 court judgments totaling around $40,000.

Stan Lee sued Olivarez on April 13, 2018, alleging “fraud, financial abuse of an elder, conversion and misappropriation of his name and likeness … involving broken alliances, abrupt expulsions and allegations of elder abuse.” The complaint alleges Olivarez was involved in buying nearly a million dollars’ worth of real estate in the older man’s name as well as stealing close to $300,000 and vials of Lee’s blood, kiting checks, and forging Lee’s signature, to cause “approximately $4.6 million to be transferred out of [his] Merrill Lynch Account without [his] authorization.” Olivarez told me that he was the victim, insisting he was acting out of a deep affection for his hero and “committed to carrying out Stan Lee’s legacy in the manner that he would want, with the respect and the dignity that it deserves. Is there anything wrong with that?”

The third Lee “adviser,” Keya Morgan—the man who was dressed like a caricature of a gangster and coached the nonagenarian through the signings at Silicon Valley Comic Con—said he met Lee around 2006 but became a prominent self-declared protector around 2016. A dandyish collector of celebrity memorabilia, he is the only figure so far singled out for investigation in the Lee abuse case by the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s office. He was arrested in 2019 on felony charges of false imprisonment and grand theft from an elder and a misdemeanor charge of elder abuse, according to police.

The details of Morgan’s—and others’—relationships are complicated; Anderson, Olivarez and Morgan all wove into and out of Lee’s life with an ever-growing range of “opportunities,” business ventures and PR escapades. Olivarez persuaded Lee to use his own blood to mark collector’s-edition comic books and jack up the price, and then—as noted—allegedly stole the blood. (“Stan literally put his blood, sweat and tears into this [charity project] and was excited and thrilled about it,” Olivarez told me.) And there are photos of Morgan and Lee chumming around awkwardly with actors Leonardo DiCaprio and Robert De Niro, singer Michael Bolton and the king of Saudi Arabia.

"You could see what I did for him, which was showing kindness, love, compassion — you know, holding his hand every day. And he didn’t do that with anyone else.”

Once again, anyone who dug into Morgan’s past could have spotted evidence of mischief and deceit. When I asked around in the memorabilia world about his reputation as a peddler of presidential and Hollywood collectibles, prominent archivists and curators practically begged me to expose his schemes. For years he had hawked a “secret” Marilyn Monroe sex tape that he never produced. He claimed he slept with Lincoln’s pocket watch, though that, too, was a canard. I tried to talk to him about all of this, but Stan Lee remained subject number one for him. Tending to Lee in his final years was a calling from on high, said Morgan.

“I loved the man—he’s like a father to me,” Morgan explained when we met at his lawyer’s office last fall. He spoke nonstop for almost six hours. “He’s my childhood hero—and when he asked me to help him, I couldn’t say no.”

“It doesn’t matter if a thousand liars write a thousand articles. It will never, ever change my relationship with Stan,” he added. “You could see what I did for him, which was showing kindness, love, compassion—you know, holding his hand every day. And he didn’t do that with anyone else.”

BETWEEN ANDERSON, Olivarez and Morgan, it is hard to believe that there could be room for others to take advantage. But it was Lee’s only child who sources said appeared to control and torment him the most in the end. That might sound shocking, but it’s hardly unusual: In almost 90 percent of elder-abuse cases, the perpetrator is a family member, usually an adult child or spouse. “It’s a big reason so many cases go unreported,” Renee Rose told me. “The parental shame and guilt can be paralyzing.”

In the winter of 2014, Stan and Joanie reportedly got into a spat with J.C. over a new Jaguar convertible leased under the family trust. J.C. was said to be furious that the car wasn’t purchased outright for her. What began as a tantrum apparently turned into a shoving match. On a podcast about Lee’s final days, his then business manager, Brad Herman, claimed J.C. erupted in anger, grabbed her father’s neck and slammed his head into the back of a chair. Herman showed me photos of the contusion on the back of Stan’s head, plus a big bruise on Joanie’s arm and burst blood vessels on her legs. He told me that Stan had begged him not to go to the police, for fear of destroying his daughter.

Part IV: What Just Happened?

BY JANUARY 2018, in Lee’s last year of life, his health was quickly deteriorating. That month he was admitted to Cedars-Sinai hospital with an irregular heartbeat and shortness of breath. In a few weeks, he came down with “a little bout of pneumonia,” as he later told worried fans in a recorded video message. But it speaks to how desperate he must have felt: He dragged himself to his new lawyer Tom Lallas’ office on February 13 to sign a scathing declaration about the chaos inside his home on Hollywood’s Oriole Way.

In the document, Lee portrayed J.C. as a grownup child “with very few adult friends” who “has never had the ability to understand or manage money,” even as she “demanded ‘more more more.’ ” He detailed her wild spending sprees and said that setting limits was useless. “When J.C. and I disagree—which is often—she typically yells and screams at me, and cries hysterically if I do not capitulate.”

Nothing was enough for J.C., according to the document. She had regularly fought for her parents to amend their trust in order to put assets and property deeds in her name, insisting that, “This is my money, I want my money.” Such a change, J.C.’s father predicted, would “greatly increase the likelihood of her greatest fear: that after my death, she will become homeless and destitute.”

You can feel a father’s heartache in every paragraph, as he goes deeper into J.C.’s associations with what he calls the three “bad actors”—Olivarez, Morgan, and J.C.’s attorney, Kirk Schenck. (Interestingly, Anderson was not named.) Lee said they worked their way into the financial dealings “of a vulnerable woman without a support system who is an easy target for predators,” in order to “gain control of my assets, property and money.”

"My father and I were best friends. I’m sure you’ve researched and heard how many public statements my father made about how I was his ‘greatest creation’ and ‘the love of his life’ along with my mother."

But then something inexplicable happened. Within two days, on February 15, Lee changed his mind (or someone changed it for him), firing attorney Lallas and replacing much of Lee’s staff. As the Los Angeles police arrived at Lee’s home that day to investigate reports of elder abuse, it appeared that Keya Morgan had ascended to some lofty position that left him in charge of Lee’s domicile, and had swiftly taken full control of Lee’s life and career.

Morgan barred the doors and tried to prevent Lee’s nurse, Linda Sanchez, and others who had worked in the home from talking to officers and reporters, and may have forced some workers to sign nondisclosure agreements. Lee’s longtime accountants were fired, and a new lawyer was retained. Lee’s assistant of 25 years, Mike Kelly, suddenly required permission and supervision when visiting. (Kelly didn’t respond to multiple interview requests.) Lee’s home phone number and door locks were changed, and Morgan began monitoring and even writing Lee’s emails, Twitter posts and public statements. (Though, in fairness, because of his failing eyesight, Lee had long required some help with those tasks.)

It was bedlam at a time when Stan Lee should have been savoring these days: That same week saw the national release of Black Panther, about an African Marvel character that Lee was most proud of. (It would earn three Oscars and $1.3 billion at the box office.) Instead, Lee was dealing with one new mess after another.

On February 20, Sanchez, the nurse, made a formal legal declaration that painted her work environment at the Lee home as a living nightmare, with J.C. constantly assaulting her father verbally and J.C.’s lawyer, Schenck, acting like a schoolyard bully, demanding that Sanchez sign a nondisclosure agreement. When Sanchez announced she was pregnant shortly before leaving her job that winter, J.C. reportedly left unhinged messages on Lallas’ voicemail, suggesting that Stan might be the father.

Lee appeared in another recorded message in June, looking as forlorn as a POW, staring dead-eyed into the camera to assure everyone that he and Morgan were “conquering the world, side by side.” The authorities were not buying it.

In the middle of August, three months before Lee died, a Los Angeles Superior Court judge granted Lallas’ request for a restraining order against Morgan. It accused him of mishandling more than $5 million of Lee’s artwork and money while attempting to isolate Lee further from his family by moving him to an undisclosed apartment. Morgan called it “fake, fraudulent news” but then dropped out of sight.

By the time Lee conducted the final media interview of his life, on October 8, J.C.’s attorney, Kirk Schenck, bragged that they’d “kicked out … the bad guys.” When asked about the “chaos” in his home, Stan Lee did his best to give it a positive spin: “There really isn’t that much drama. As far as I’m concerned, we have a wonderful life. I’m pretty damn lucky. I love my daughter, I’m hoping that she loves me, and I couldn’t ask for a better life. If only my wife was still with us. I don’t know what this is all about.”

Part V: A Free Man That Night

ON THE LAST EVENING of Lee’s life, he had his usual early supper—plain fish, a roll with butter, strawberry Jell-O for dessert. It was a Sunday, around 8 p.m., and Jonathan Bolerjack—his friend, driver, assistant and perhaps one of the only people in Lee’s inner circle who seemed to show true empathy for a man in his final days—left the house on Oriole Way, looking Lee in the eye and thanking him, as he always did.

“Some nights I would leave and think, Oh, this could be the night, because Stan didn’t look that great, but he looked fine as I headed out,” he noted. “Looking back, I feel comfortable saying Stan was a free man that night. Keya was gone, Max and Jerry were long gone, and J.C. wasn’t there then. I like to think his life ended on his own terms.”

Before bed, Lee enjoyed having one of his nurses read to him from the epic Persian poem The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, with its ancient wisdom about living life to the fullest, including lines such as “Ah, make the most of what we yet may spend before we too into the dust descend.”

Sometime before morning, Lee went into cardiac arrest and respiratory failure. Someone called 911. J.C. drove over from her apartment and went with the ambulance and a security guard to Cedars-Sinai hospital, where Lee was pronounced dead at 9:17 a.m. There was no autopsy, and he was cremated. His death certificate distilled his magnificent career to a single word: “Writer.”

“I cried a lot. Everybody was crying,” said Bolerjack, who arrived around 9:30 that morning. He admitted his emotions were mixed. “I guess I read too many comic books where the heroes win and the bad guys go down, but that didn’t happen and that’s what was upsetting.”

When I heard the news, I had a flashback to my times with Lee. One comment leaped out at me. I was asking about his influence and legacy as a towering great of pop culture when it dawned on me that Lee wasn’t quite buying his own hype.

“To tell you the truth, I never thought of myself as much of a success,” he said, and I could tell it wasn’t false humility. “When I was younger, I was embarrassed about the things I wrote. I felt there were men building bridges, doing medical research. And here I am writing these ridiculous comic book stories.” He admitted it was his years of interacting with fans that made him recognize some value in his work. He needed them as much as they needed him. Lee said, “People always tell me things like, ‘When I was a child, my mother was gone, my father was drunk, but your comic books were there for me.’ These characters are important to people in ways I can’t even understand. But is that success? Is it being wealthy? I know a lot of people richer than I am. Is it being happy all the time? Nobody’s happy all the time. But then again, I don’t think anybody ever stops a bridge builder on the street and says, ‘Your bridges! They’re thrilling!’

Part VI: Love and Theft

THE LAWSUITS churn through the system. Delays give way to delays, and the accused sit mostly at home like the rest of us this year. As with so many elder-abuse cases, those involving the Lee estate will likely come down to “he said, she said.” Except, in this situation, there’s a three-ring circus of barkers and performers who may not have had Lee’s best interest at heart, in a charade that went on for years. Call it the long con, but “those types of relationships are much more difficult to pinpoint as being perpetrators,” said elder-abuse prosecutor Paul Greenwood. “I always say that the longer the victim and suspect have known each other, the more difficult it becomes to establish beyond a reasonable doubt that undue influence was exerted over that person, because sometimes loyalty is rewarded.”

In a less lawyerly explanation, the villain in this story is love. Abuse of the elderly routinely cloaks itself in love, which is, in many cases, returned by the victim. The perpetrators might even call love their motivation.

“What makes these cases challenging sometimes is that you have potential suspects who appear to have shown the victim affection, allegiance, loyalty and protection,” Greenwood said. “It can be difficult to distinguish between criminal motives and genuine concern. That’s why we always look outside the immediate circle to neutral observers who didn’t have rewards to gain, and who weren’t endearing themselves with opportunities to enrich themselves.”

And now Joan Celia Lee is in charge of her father’s legacy. She owns the family homes and controls the finances of his massive estate. Even during the coronavirus shutdown this spring, she was in court pursuing rights to her father’s intellectual property. I reached her on the phone one day after weeks of trying. With her father gone, I wondered why she was still suing everyone in sight. I asked gently, “So, what do you want now?”

“I want everything that’s mine!” she snapped. “I want my museum, I want to do a restaurant — Stan Lee’s Super Subs — I want to do a big Spider-Man Stan monument to put my family’s ashes somewhere.” At that point, she broke into sobs. “I want help. I’m the one who’s been abused.”

J.C. Lee, the loving daughter, cursed and ranted and blamed her father’s troubles on Hollywood corporate greed, the evil media and even Scientology. On the whole, she sounded like a woman engaged in battle, unaware that she had won the victory. The empire was hers.

She told me she couldn’t talk to me anymore. She told me to “do whatever the f--- you want.” She said she was going to write about me, too. She said that God sees all. She threatened to sue me. Then she hung up. Schenck, her lawyer, wrote me back a week later on her behalf with an official-sounding email statement that painted J.C. as a misunderstood figure who really just loves and misses her parents.

“My father and I were best friends,” the email said. “I’m sure you’ve researched and heard how many public statements my father made about how I was his ‘greatest creation’ and ‘the love of his life’ along with my mother. The three of us were inseparable my whole life. I may have frustrated them, and they certainly frustrated me on occasion. But we loved each other and aside from private statements falsely induced by the recorder in each instance, the record reflects this.”

David Hochman is a contributing editor to AARP The Magazine

Elder Abuse

How to get help:

- People who witness someone in urgent danger should call 911.

- Victims and people who would like to report elder abuse should call Eldercare Locator at 800-677-1116 or the Adult Abuse Hotline at 800-222-8000.

Other resources: