AARP Hearing Center

For many women, menopause comes as a relief: an end to pregnancy worries and monthly cramps, a farewell to bloodstained panties and premenstrual mood swings. Though menopause signals the opening of a historically uncelebrated chapter in a woman’s journey, lots of women are thrilled to cross its threshold.

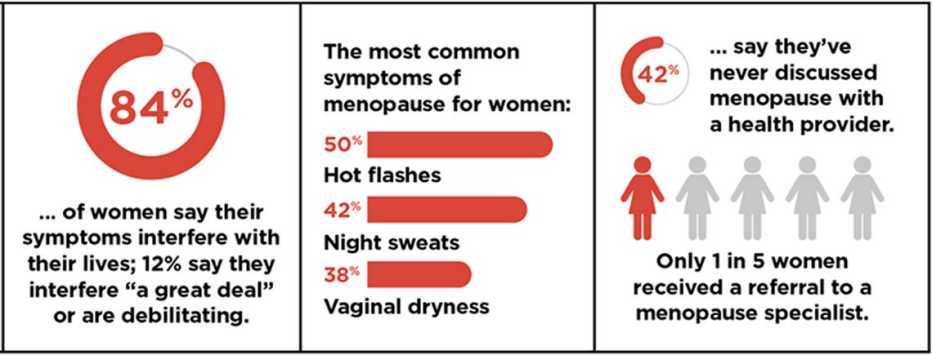

Others loathe the passage. For them it’s a journey often punctuated by hot flashes, insomnia and, in numerous cases, sexual dysfunction — symptoms that for some can continue for 15 years or longer. These episodes can make women in their 50s and 60s feel uncomfortable, demoralized and sometimes seriously ill.

But regardless of one’s attitude toward it, the onset of menopause means a marked increase in certain health risks. For example, hormonal changes result in an accelerated rise in LDL cholesterol in the 12 months following menopause, boosting the possibility of heart disease. And though both men and women suffer a loss of bone density with age, the sudden reduction in estrogen associated with menopause has been shown to trigger an inflammatory reaction in some women that leads to a dramatic decrease in bone mass. These issues lurk beneath a host of distracting and sometimes debilitating physical conditions, large and small, from night sweats to weight gain to concentration problems.

And though menopause medications that can help alleviate discomfort — and perhaps prevent or delay the onset of chronic disease — have been around for decades in various forms, research indicates that just a small minority of menopausal women are receiving the medical care they deserve. A Yale University review of insurance claims from more than 500,000 women in various stages of menopause states that while 60 percent of women with significant menopausal symptoms seek medical attention, nearly three-quarters of them are left untreated.

“Doctors are not helpful,” says Philip M. Sarrel, professor emeritus of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive services, and of psychiatry, at the Yale School of Medicine. “They haven’t had training, and they’re not up to date.”

“Nearly one-third of this country’s women are postmenopausal,” says gynecologist Wen Shen, an assistant professor in the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics. “Many of them are needlessly suffering.”

"Doctor, what's happening?"

Carrie Haine is in tears. She is petite, attractive, the type of woman whom you easily envision as a popular “it” girl when she was in high school or college. Now the former third-grade teacher is 57, and while she has had some relief lately, her body has been betraying her. Sleep has grown elusive. Hot flashes have stolen her focus. Sex has hurt.

“It’s a hard thing to face,” says the mother of two grown sons. “Your intimate understanding of your body changes.”

Haine had been trying to figure out her problem since she went off the pill four years ago. Because birth control pills contain estrogen, they can mask the onset of menopause. Within three weeks of discontinuing them, hot flashes hit Haine “like huge waves rolling into shore, then crashing on the beach,” punctuating her days “with an intensity that only someone who has experienced them can understand.” In time, she grew inexplicably anxious and soon started losing track of thoughts, often finding herself without words. She knew she was going through “the change,” yet hadn’t been prepared for “how all encompassing it was — that it wasn’t just about my body but everything about me, and I felt it not only physically but emotionally.”

Haine consulted with the male gynecologist who delivered the second of her two sons. “I didn’t feel he understood the emotional aspects of what I was going through,” she says. “And I felt he wasn’t attuned to the nuances of my body.” Later she consulted with a “lovely” female gynecologist who attempted to solve her sex-pain issue with gels and sex toys.

Then, last year, Haine had a horrifying experience. One day while at work, she got so dizzy she had to sit down. But what really concerned the school nurse was Haine’s sudden inability to speak. “I had the words, but I couldn’t say them,” she remembers. Worried that Haine was having a stroke, the nurse called an ambulance. But at the hospital, all her scans and blood work checked out. Said the doctor when he signed her discharge papers, “Maybe you need a hobby.” Turns out, Haine needed neither a sex toy nor a hobby; she needed a physician who understood how to treat menopause.

Haine tells her story from Shen’s meeting room in the Lutherville, Maryland, offices of Johns Hopkins. A few months before, Haine heard Shen speaking on the radio, on NPR. “She was talking about menopause, and her voice was really calm and soothing, and it resonated with me,” says Haine, who, like many women, and even many doctors, didn’t generally associate a shift in hormone levels with anxiety. She also didn’t realize she could find a solution for painful sex, which has since been eased with vaginal estrogen. During this latest visit, Shen is referring Haine to a psychologist to help her with some of the emotional changes that can accompany menopause for some women. “She’s looking at all the bits of me,” Haine notes. “Not just my body and how it’s changing but also how I am changing as a woman. Menopause is very personal.”

More on Health

Natural Remedies for Menopause

How to cool down — or perk up — with the handful of treatments that are backed by scienceMenopause and Sex: A Q&A With Expert Laura Berman

From hormone replacement therapy to Viagra for women, answers to your pressing questionsA Brief History of Treating Menopause

How estrogen therapy got a bad name — and why doctors now say it shouldn't have