Remembering Travis ‘Enloe’ Nash, World War II Soldier

Two families, stretching across two countries and three generations, search for clues to a boy-man who died at 21 in a foreign land

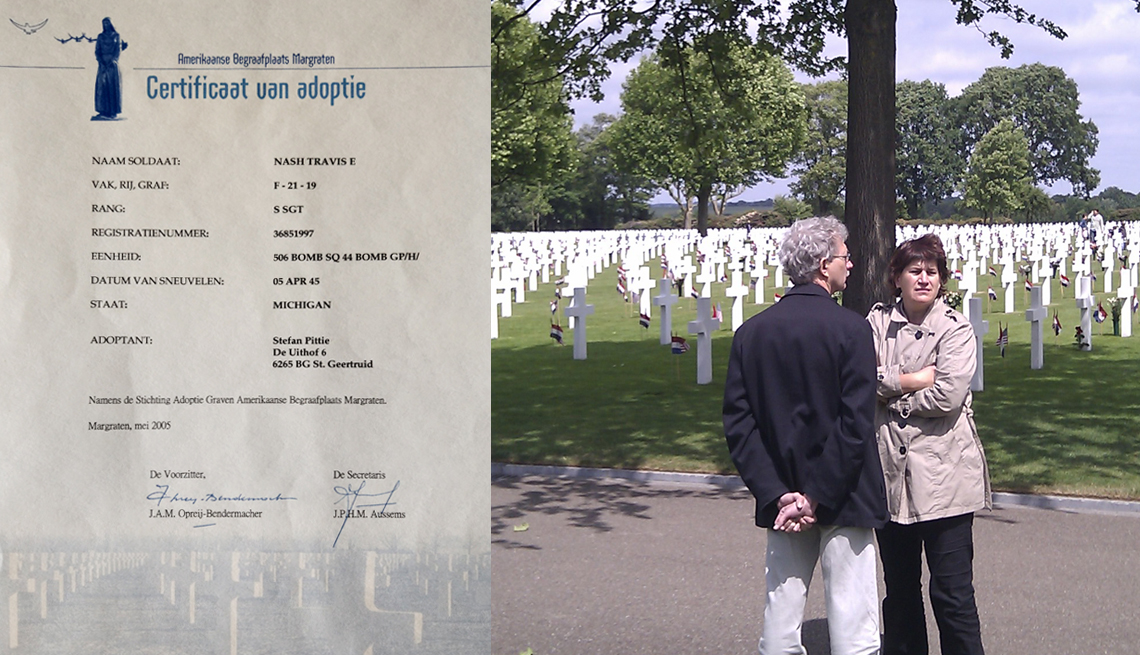

For almost half his life, Stefan Pittie, 33, has routinely laid flowers on the grave of a U.S. serviceman, killed in World War II and buried in the Netherlands American Cemetery in the Dutch town of Margraten.

"It's always overwhelming when you arrive there,” he says softly. He's referring not just to the immaculate grounds and rows and rows of white marble crosses and stars of David for the 8,301 American liberators interred there — each marker inscribed with the soldier's name, rank, and battalion, division, squadron, or group, and date of death — but to the solemnity of it all. “To be responsible for one of the heroes of the war,” he adds, and then his voice trails off. “When I come home, I'm always for maybe one hour very silent.”

In 2005, Stefan's mother, Maria, officially 'adopted' two burial sites in the names of her children, then still teenagers. (Daughter Mindy’s soldier is Private First Class John J. Paszkowski of New York, for whom no family history or photograph is available.) The Foundation for Adopting Graves American Cemetery Margraten began the program right after the war; more than 10,000 Dutch citizens tend the memory of men and women they never met. There's a waiting list of more than 900 people who wish to adopt, and the graves often stay in families for generations.

"It is important that we continue to honor our liberators for what they have done for us,” Maria says. “You realize how young and far away these boys were from home.”

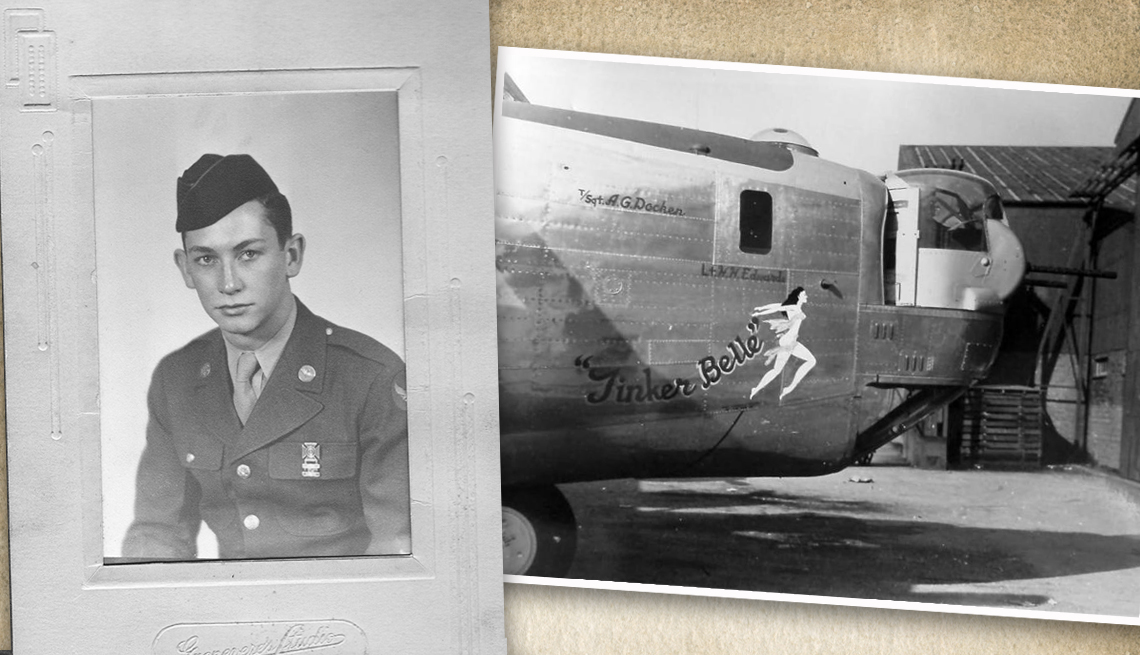

Stefan, who has had a strong interest in World War II since school days, thinks of Army Air Force Staff Sgt. Travis E. Nash, a radio operator with the 506th Bomber Squadron, 44th Bomber Group, killed in action on April 5, 1945, as his soldier.

But he is also mine: Travis was my uncle. And as with Stefan, Travis is a man I never knew. He died before I was born.

A soldier, fallen

Enloe, as my family always called Travis, using his middle name, had just sent an HF radio report that spring day in 1945 when his plane was bombarded with flak over Germany. The pilot called back to his radioman: “It's gettin’ pretty hot back there, isn't it, Nash?”

But Enloe didn't answer. He had taken a direct hit to the head and slumped over his radio table, dying in a tubby B-24 nicknamed “Tinker Belle,” returning from a bombing mission barely a month before war's end. The plane, with three damaged engines, lost altitude, and the crew bailed out, leaving Enloe to go down with the ship. The explosion from the crash threw him out of the plane, and his fellow crewmen, immediately captured as POWs, were forced to look up to see his body burning in a tree.

For years, Stefan, who knew almost no details of Enloe's life and military career, and until recently had no photograph of him, would stand at the grave and wonder why he had come so far from home to fight for a country that wasn't his own.

Sometimes, too, he says, “I wondered about the family."

Veterans and active military save up to 30% on AARP Membership. Get instant access to discounts, programs, services, and the information you need to benefit every area of your life.

A soldier's family

Through the years and stories of my family, my fallen uncle had become a romantic figure to me — I also thought I looked like him — and as long as my aunts and uncles lived, I pestered them for photographs and memories of him.

He was the youngest of 10 children born in rural Paris, Tennessee, to a carpenter-farmer and his wife, my paternal grandparents. “He was kind and gentle, and he just worshipped his mother,” my aunt Edna told me. “My husband and I took him to the bus the day he went into the service. Your grandfather gave him $30, and I remember how he hugged and kissed everybody goodbye. When he got to your grandmother, he just clung to her and wept and wept. We could hardly get him to turn loose."

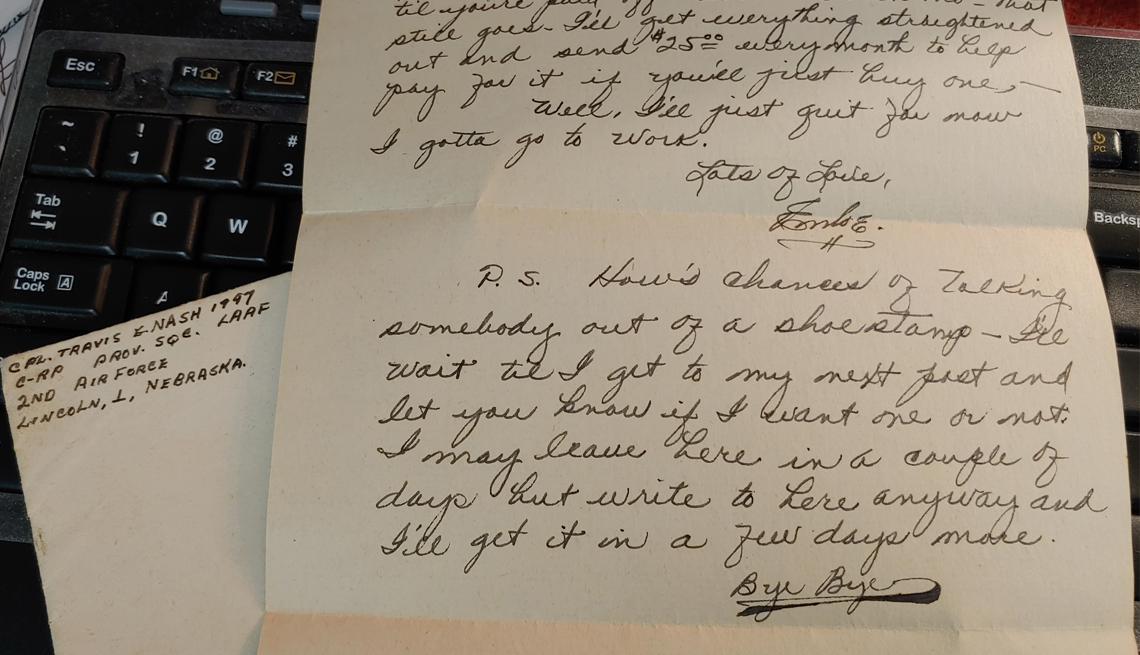

My older cousins had fleeting memories: Enloe was tall and handsome, played games, took them fishing. But my father, six years Enloe's senior and now deceased, had come to know him best. The reason? A bulging packet of letters Enloe wrote home to my grandparents from the war. “If you want to know him,” my father had said to me, “read those letters.”

Yet I did not read the letters. I knew that the essence of Enloe was on those yellowed pages with their ancient postmarks, his personality ablaze in the elegant swirls of his penmanship. But I thought it would hurt too much to find him and lose him all at once.

- |

- Photos

A chance connection

This year, I received a letter from a volunteer for the Faces of Margraten, an initiative that decorates the cemetery's graves and Walls of the Missing with photographs of the soldiers — a moving gesture to allow Europeans to “look into the eyes” of their liberators. Did I have a picture of Enloe, she asked? From that connection came a surprising follow-up: The adopter of Enloe's grave had been looking to find his soldier's family. What Stefan didn't know was that I had been looking for him, too.

That very day, we connected by email and began exchanging military files and personal photographs. In an emotional Skype call, I promised to finally read the fat packet of Enloe's letters.

Holding them almost made me tremble. I could feel my uncle on the pages as he described his duties in America before being sent to England in January 1945. Inside the envelopes were plans for future visits, reports of drinking beer and dancing in English pubs, and requests: for socks and handkerchiefs, a frame for a picture of a girl from home, and for his family's prayers that he would make it back alive.

Tucked inside the packet were three photos that I had never seen, including one of him in London in his last months. They took my breath away.

In late 1944, he wrote a long letter home in which he talked effusively of hoping to fly a B-29. “If I do get on this type plane, I'll hardly even stand a chance of being killed in the air,” he said.

On March 29, in one of his last V-Mail letters, he wrote to his brother Warren and his family. “Fighter opposition is almost nil now,” he reported, “but the flak is the roughest now than in any other part of the war.” A week later, it got him.

The letters so moved me that I immediately began scanning and sending them to Stefan. Suddenly, a name on a marble cross became a flesh-and-blood person for both of us.

In a way, we are extended family now. “It is unreal that this has happened to us, and I am so honored and pleased to have contact with you!” Stefan's mother wrote. I offered to send another photo — this time, of me. “We searched so long!” I told her I would like to come back some day and meet her. Until then, “We shall bring your love and our flowers to your uncle,” she said, “and lay down your picture beside him.”

Resources

Relatives of fallen World War II military may inquire about the adopters through these websites: