Fraudulent Freelancer Breaks Down a Sweepstakes Scam

Master designer of phony direct mail packages shares how he convinced millions they won big money

En español | Crime movies don't have it wrong: To pull off a really big caper, you start by assembling the best team possible.

For roughly 30 years, if the caper you were planning was to defraud lots of people through a bogus direct-mail campaign, that very possibly meant hiring Steven Thomas (not his real name). Thomas was considered one of the most effective writers and designers of fraudulent mail — in particular, bogus sweepstakes mailings — ever to operate in America.

Thomas was a gun for hire, a high-priced freelancer. He didn't want anything to do with all the many details of operating a fraudulent business. He fulfilled one key task: write and design mailers that sparked the largest possible response. His typical pay? About $20,000 a month. Over the years, he claims, he worked for hundreds of businesses.

Thomas, 68, is now in prison. In 2018 he was charged with mail fraud as part of a federal government takedown of over 200 illicit sweepstakes operations worldwide. How effective was his work? According to the charging documents, his mailers for one client persuaded 400,000 victims to send in over $50 million between 2012 and 2016.

In 2018 Thomas pleaded guilty to the charge against him, and today he resides in a federal “camp,” as he put it, in the California desert. That's where I met him early this year, before the pandemic hit. After a series of letters back and forth, he agreed to spend several hours with me discussing the secrets of the illegal sweepstakes game. Even though his name is in the public record, he agreed to talk only if we used a pseudonym. And talk he did, throughout an afternoon. Here are some of the stories and secrets of fraud he shared with me.

Learning his craft

Thomas first started working for companies that used a sweepstakes as a hook to sell something -— coins, clothing, cleaning products — a marketing practice that continues to this day. Such practices are legal, provided the recipient is not required to buy anything or pay money to enter. Thomas claims those early employers were legitimate and that he was quite successful.

But his employers kept demanding higher and higher response rates, and he was running out of ideas for how to keep people coming back for more. So he decided to go to the best graduate school he could find. He went to Las Vegas.

AARP Membership -Join AARP for just $12 for your first year when you enroll in automatic renewal

Join today and save 25% off the standard annual rate. Get instant access to discounts, programs, services, and the information you need to benefit every area of your life.

"I'd go into a casino, I'd sit at the bar. I'd get a beer, and I'd just watch people, watch what machines they played and how often they'd sit there,” he told me. “And they didn't walk away with anything. I couldn't believe that they'd just play and play and play and lose."

What Thomas learned is that, like lotteries, the casinos weren't selling a legitimate chance of winning. They were selling the chance to imagine a better life. “There's a young guy, he's 22 years old. He says to me, ‘I'm never gonna buy a company. I don't have a college education. But if I buy a ticket for a buck, I could win $40 million, and then I could buy a company. Hey, Steve, what company should we buy? Let's buy that trucking company down the street.’ “

Starting then, Thomas made the selling of hope the key psychological strategy of his mailers. Give people permission to imagine they may have finally drawn a lucky card in life — then make them pay for it. He actually created a checklist of 24 elements to include in each mail piece to maximize this perception.

Bold images, power words

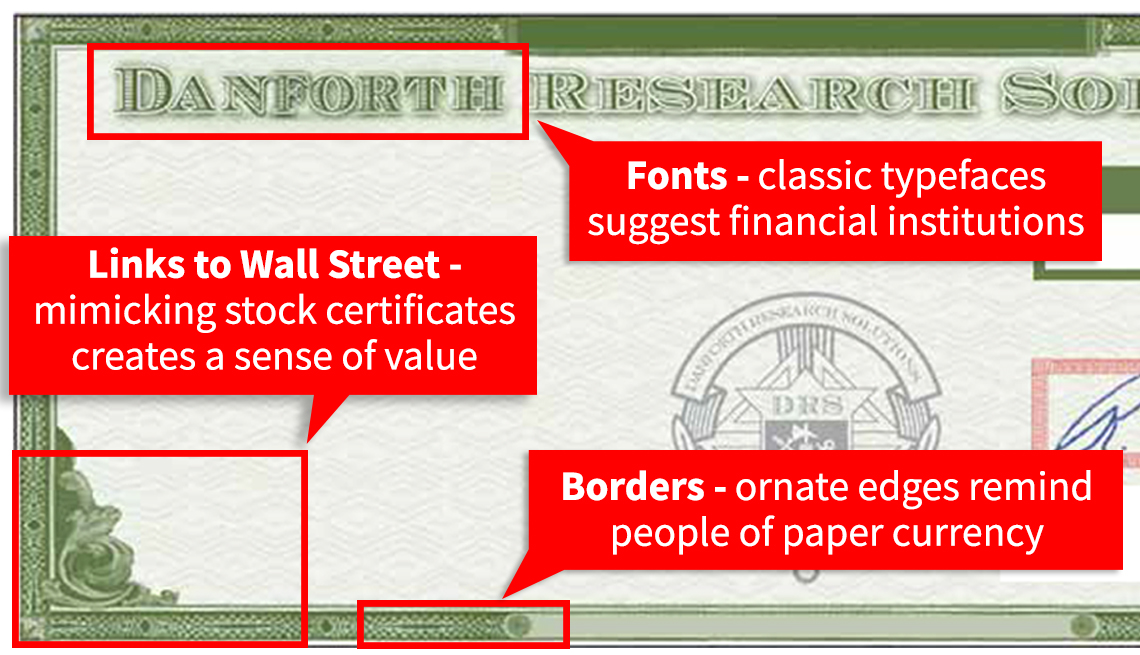

Here's your vocabulary word of the day: scripophily. It refers to the study and collection of old bond and stock certificates. Thomas mentioned the word to me several times, because it was central to his success. He extensively used stock certificate images in his designs — complete with official seals, images of birds of prey and ornate presentation — as a way to make his sweepstakes mailings look legitimate. As he explained, when companies first started issuing stock, they had to convince investors that they were getting something of real value, so they would use similar techniques. Many of Thomas’ design images drew on scripophily to convey a sense of authority, stability and wealth.

He learned through trial and error that subtle light blue and gray worked better than bright, splashy colors, which made the mailings look like cheap ads. He would also use classic, official-looking fonts like Bank Script and Copperplate to make the mailings look like they were produced by a financial institution. He used images of pillars, seals, embossings and ornate borders called guilloche. “Guilloche is what we see on our dollar bills, certificates and diplomas,” he said. And he frequently used images of golden wreaths. “Winners in the Olympics thousands of years ago were given oak golden wreaths. These images eventually found their way onto coins. Go look at the images on the hotels in Vegas.”

What about government images, like presidents or flags? Thomas gave me an emphatic no, saying the lawyers never allowed him to use anything that made the mailing look like it came from a government agency; that would prompt suspicion and reduce its effectiveness.

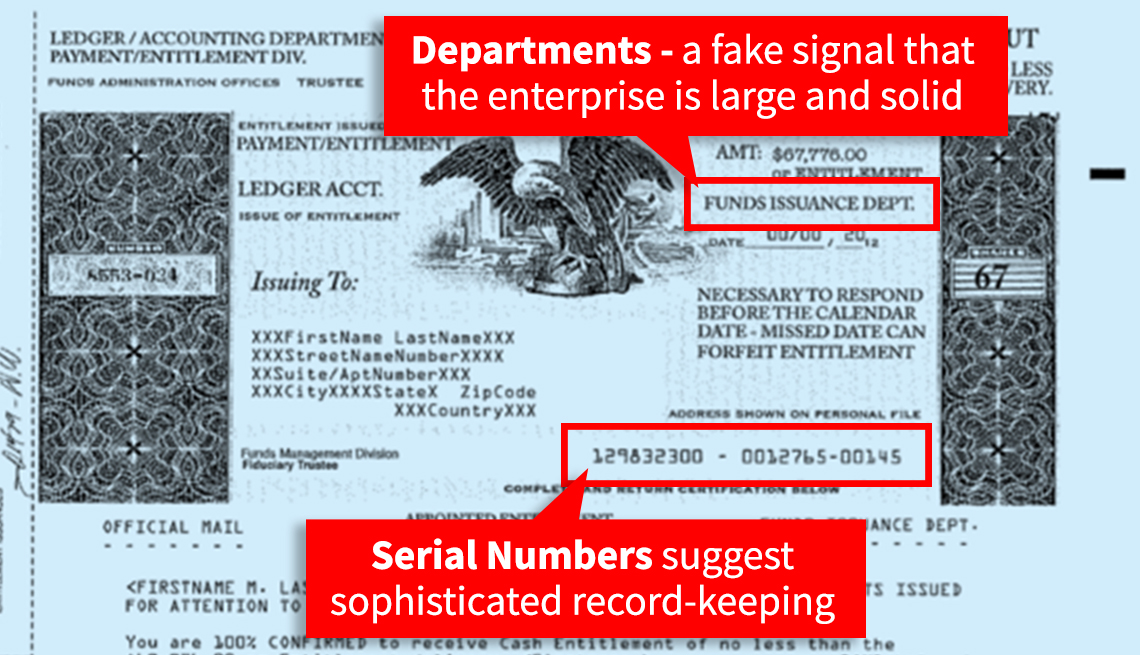

Key words were another tool. Thomas employed words like “guaranteed,” “entitlement,” “ledger account,” “100% confirmed” and “funds issuance department” to convey trustworthiness and believability. He also discovered through trial and error other powerful words, like “report” and “candidate,” which he believes work because all of us had childhood experiences with these words, and that makes us pay attention (think “report card"). The word “candidate” draws victims in and encourages them to feel part of the program.

How to Spot a Sweepstakes Scams

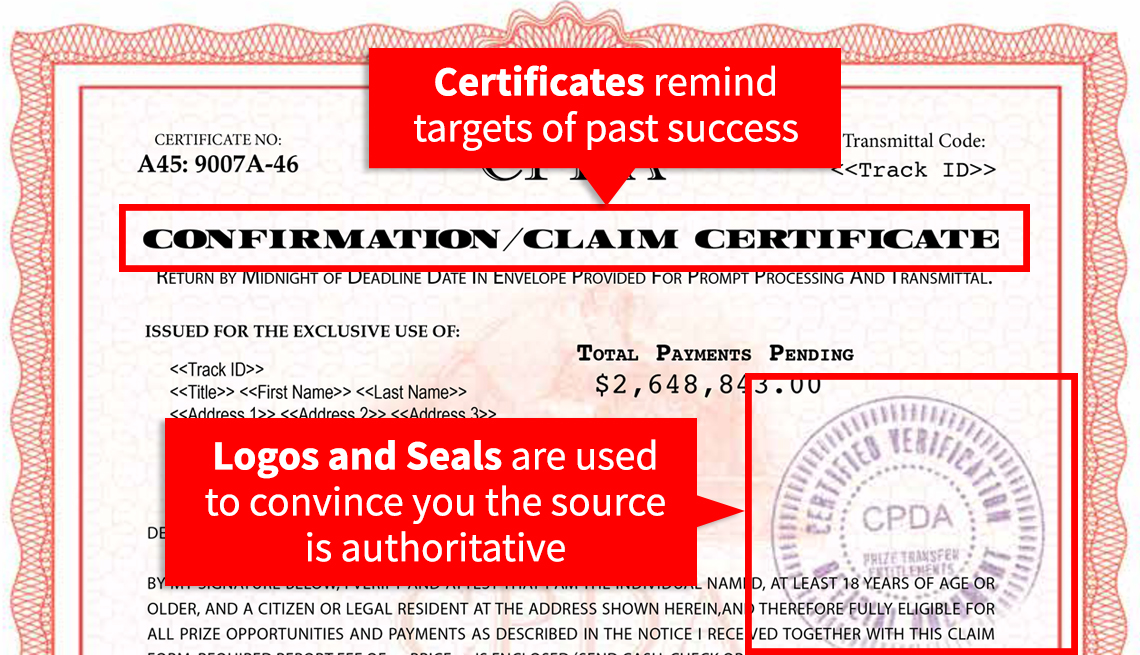

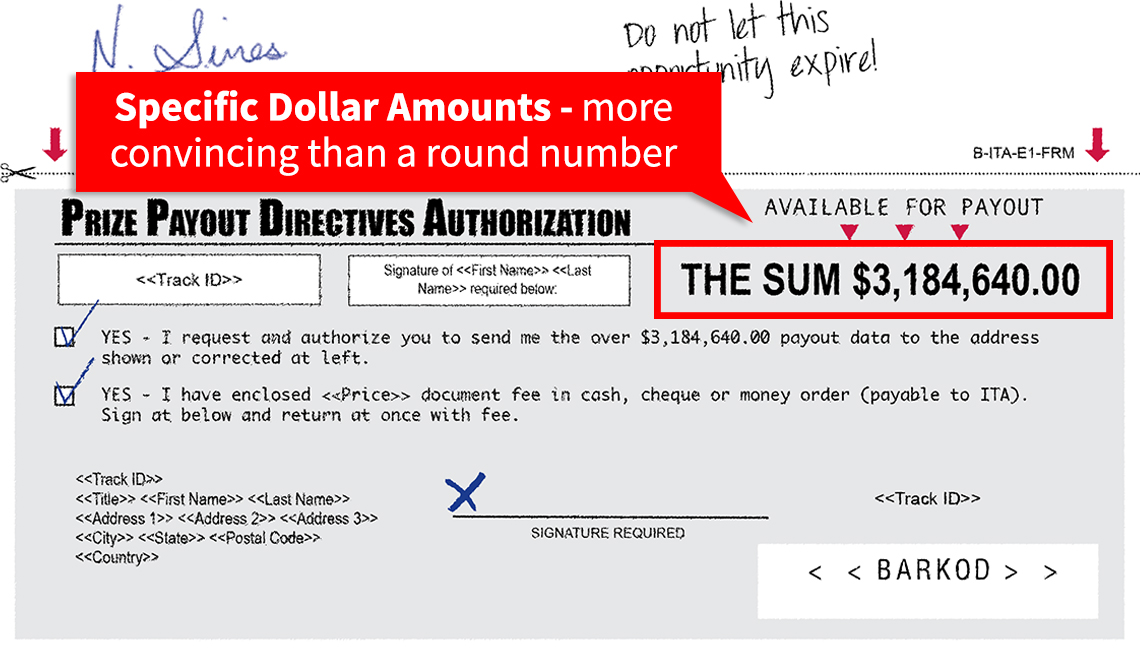

Thomas created a checklist of elements to include in each mail piece to maximize their success rates. Here's what to keep an eye out for.

Actual sweepstakes documents written and designed by “Steven Thomas.” All were presented as evidence at his criminal trial.

- |

- Photos

Thomas would frequently place two or three signatures on the mail piece from someone with an impressive-sounding title, like “Director of Account Compliance” or “Fiduciary Trustee,” to convey authority and believability. Federal authorities I spoke to said these documents were not signed by company officials but rather by their creators — like Thomas himself, who considered his signatures just another part of the design. The truth is that none of the company names or people existed.

Thomas also would add a lot of numbers in various places on the mailer, labeled “Winners Claim ID No.” or “Record Reference ID.” When I asked him what the numbers mean, he said, “They mean nothing. They just complete the design.” The goal was to leave a net impression that the company and the offer were legitimate.

The personal touch

Another tactic that caused response rates to soar, according to Thomas, was personalizing the letters. If the potential victim's name was Joan Smith, they developed software that would sprinkle “Joan Smith” throughout the letter. Once she saw her name on the page, she was more likely to believe the letter was actually written only for her. The reality is that software allowed the mass production of millions of identical letters, with only the recipient's name varying between them. Today pretty much every company with a marketing department has learned this trick, so most unsolicited letters or emails you get have your name all over them.

Another tactic that really worked was to include in the mailing an official-looking certificate that had the victim's name printed on it. Why?"Do you remember the first time you got a certificate for sports or for good grades and saw your name in print?” Thomas said. “How did it make you feel?” Once a victim sees his name on an image that looks like a stock certificate or a diploma, it triggers some of those early emotions of pride and positive feelings and makes the victim want to continue.

Getting victims engaged

Thomas next explained that to make victims feel like they were part of something important, he required them to sign a response card. Or he would require respondents to solve a simple puzzle or answer quiz questions so they would feel like they were actually earning the prize and were therefore invested in the outcome. His goal was to make the victim, especially one who might be lonely, feel like he was a part of something, by actually making him do something.

"Picture a woman sitting in her apartment in the Bronx, and she's sitting up there on the 20th floor and she's looking out, going, ‘Is there going to be any life for me other than this?’ So she goes through her mailbox and says, ‘What's this? I could win $10,000? That's enough to get me out of here. And if not, one thing for sure is at least I am being included. Someone's thinking about me, thank God.’ At that point, she doesn't even care if she wins. She's gonna sign it and send it in and just hope to hear back. And she is gonna hear back: ‘Thank you, Miss Smith. We received your order form. Please find your … ’ “

Of course, the biggest hook of all was the biggest lie: a claim that the mailer recipient had won big money. Thomas said they would often make the amount very specific, like $937,425 instead of $1,000,000, so it would appear more legitimate, as if someone in an accounting office somewhere had calculated the amount.

The fraud, of course, was that to collect their prize, the “winner” first had to pay various fees and expenses. For decades now, millions of Americans have sadly obliged, and of course received nothing in return.

Parting words

Throughout our interview, I couldn't help but be taken in by Thomas’ pleasant demeanor and what appeared to be a sincere desire to help us warn people about direct-mail scams. And his insights about how he and others developed effective sweepstakes mailers has indeed been helpful to law enforcement and fraud-prevention advocates — and now, hopefully, to you, too.

But I was bothered that Thomas kept telling me he was just a very skilled artist who got caught up with the wrong crowd, implying he never really wanted to hurt anyone. He even suggested his goal all along was to make people happy. “Phineas T. Barnum, the greatest marketer that ever lived, said the noblest art is that which makes people happy,” he told me as I was preparing to leave the prison. “And I followed that. I wanted to make people happy.”

It made me think of something else about P.T. Barnum: much of what he sold to the public was hoaxes and deceptions.

AARP’s Fraud Watch Network can help you spot and avoid scams. Sign up for free Watchdog Alerts, review our scam-tracking map, or call our toll-free fraud helpline at 877-908-3360 if you or a loved one suspect you’ve been a victim.