Challenger Disaster: Fire in the Sky

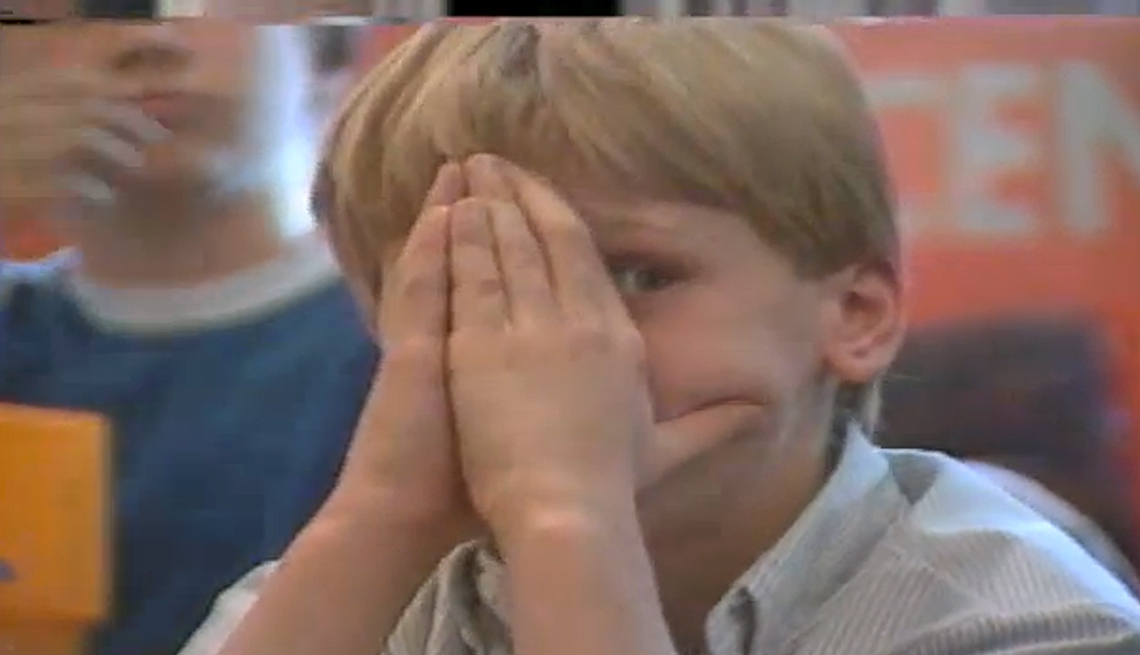

When the space shuttle exploded 30 years ago, a generation of students watched it happen

Bruce Weaver/AP

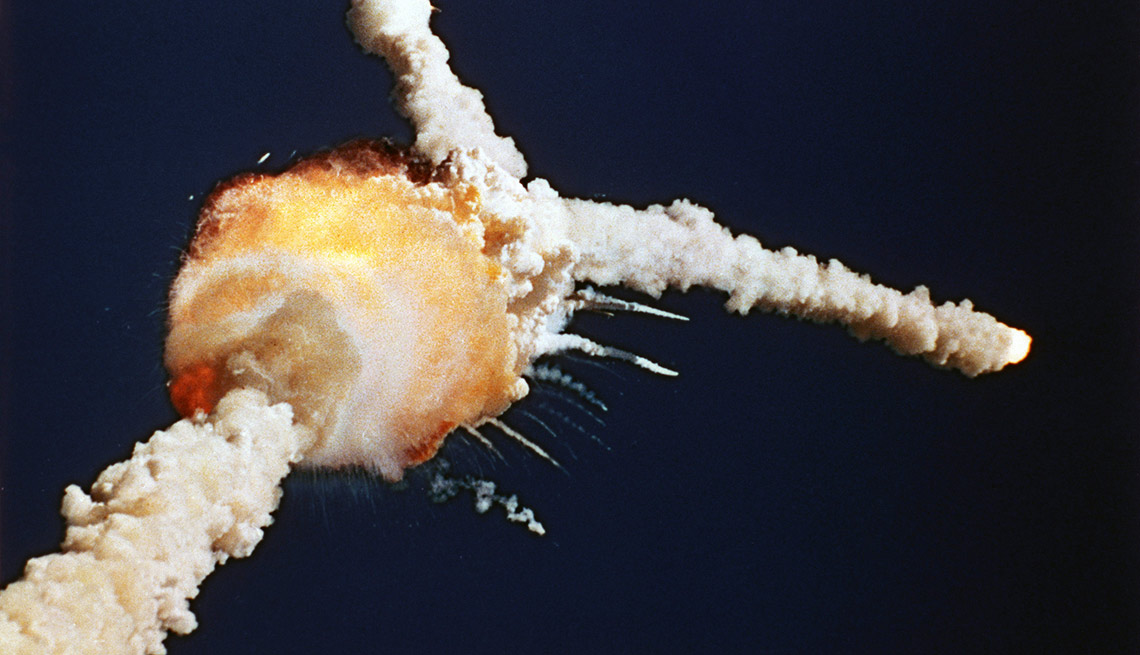

The space shuttle Challenger explodes shortly after lifting off from the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Fla., on Jan. 28, 1986.

Some public schools let the kids watch TV that morning, but not mine. For those of us in the Central time zone, the Challenger explosion happened at 10:39 a.m. on January 28. I didn't hear anything about it until 12:45 p.m. In 1986, the idea of knowing anything immediately was so rare that no one assumed it was remotely necessary.

My 22 classmates and I were told by my earth science teacher, who delivered the information like he was setting up a joke with no punch line. "The space shuttle exploded this morning and nobody survived," he said. Then he stood there, waiting for us to react. It was more confusing than shocking. A kid in the back of the room asked, "What do you mean by 'exploded?'"

There were no details — the stuff about O-rings didn't come out for weeks. My teacher gave a cursory visual description of the explosion before going into a 20-minute lecture about how several of his colleagues had urged him to apply for the shuttle seat that was awarded to Christa McAuliffe, the New Hampshire social studies instructor who was the first participant in NASA's Teacher in Space program. He told us he had declined because he knew something like this might happen. Coming from a man who was 50 pounds overweight and smoked two packs of cigarettes a day, this seemed specious; he was probably not the ideal candidate for astronaut school.

If the tragedy had occurred in 2016, I suspect school might have been dismissed for the rest of the day, in deference to the student body's emotional well-being. But it was 1986 in rural North Dakota. They didn't even cancel basketball practice.

Space Frontiers/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Frederick Gregory and Richard O. Covey, spacecraft communicators at Mission Control in Houston, watch helplessly as the shuttle Challenger explodes on Jan. 28, 1986.

Still, we all knew this particular moment was a different level of news. It felt like the first undeniably historical event people my age had experienced. When I went to college in 1990, it was the only event absolutely everyone I met could recall with total lucidity. For a time, it seemed like the Challenger explosion might remain the defining cultural memory for Generation X (until it was usurped by the O.J. Simpson Ford Bronco chase in 1994 and then the terrorist attacks of 2001). It was sad, certainly. It was disturbing to imagine what it must have been like for the seven crew members in the moment they realized their existence was disintegrating. But the sadness and the horror were almost ancillary. What was truly disturbing was best encapsulated by the kid who'd asked, "What do you mean by 'exploded?'"

Prior to that day, it had never occurred to me that NASA could fail so dramatically that people would die. In retrospect, it seems crazy that I thought this way, but at the time, space exploration no longer seemed dangerous. Shuttles landed on runways like commercial 747s. It's essential to remember that one of the reasons the Challenger was carrying a social studies teacher (with only a year of astronaut training) was because Americans were literally bored with space travel. President Ronald Reagan had proposed the notion of rocketing a schoolteacher into orbit in a 1984 speech, to remind Americans about the "crucial role of teachers and education in U.S. national life." Bizarrely, the whole thing was a kind of publicity stunt.

A few years after the accident, I was a 16-year-old junior in a U.S. history class taught by my high school's principal. Near the end of the semester, he mentioned how being a history teacher is a strange job, because of the passage of time itself. He couldn't comprehend how a student born in 1972 might view the moon landings the same way he viewed Civil War battles — as historical occurrences, detached from personal memory. To him, the Apollo missions still felt like living events.

NASA

The Challenger crew at NASA's Kennedy Space Center. Left to right are Christa McAuliffe; Gregory Jarvis; Judith A. Resnik; Francis R. (Dick) Scobee, mission commander; Ronald E. McNair; Mike J. Smith; and Ellison S. Onizuka.

Because I was a talkative student, I tried to disagree with him on this point. I said I understood the difference between 1969 and 1864, and I fully realized that Neil Armstrong was still living and Jefferson Davis was long dead, and that it was mildly insulting to suggest otherwise. "You're not really getting what I'm saying," he replied. I rephrased my response, this time complaining about how ancient history was prioritized over recent history, and that this incongruity creates intellectual dissonance for young people. "No, you're still missing the point," he said. "You're just not getting what I mean by this."

Now that I'm 43, I finally understand how correct my principal was.

Any historical moment can be learned in class, but you actually need to be there in order to understand why these things matter as much as they do. Emotional memories don't translate through textbooks. The Challenger reminded post-Vietnam America of something we'd let ourselves forget: the enormous danger and difficulty of space travel. This was not a movie about going to the moon. This was not a scientific exercise or a technological demonstration of American exceptionalism. These were metal machines, built by flawed humans and blasted into the sky. And they could break.

Suddenly, we were all unconsciously asking questions about the space program that had not been asked for years: What are we getting from this, really? What is the larger motive here? Are we underrating the risk these voyages incur? Are we overrating our confidence in the people conducting them? And if NASA isn't infallible, what other institutions should we worry about? It introduced a generational skepticism about reality itself.

It seems odd to say the most important mission in the shuttle program was its most cataclysmic failure. But it was, because that's how history works.

Writer and journalist Chuck Klosterman's most recent book is I Wear the Black Hat: Grappling with Villains (Real and Imagined).