One Year Ago: California's Deadliest Wildfire Ravaged Town of Paradise

Most of the victims were older Americans

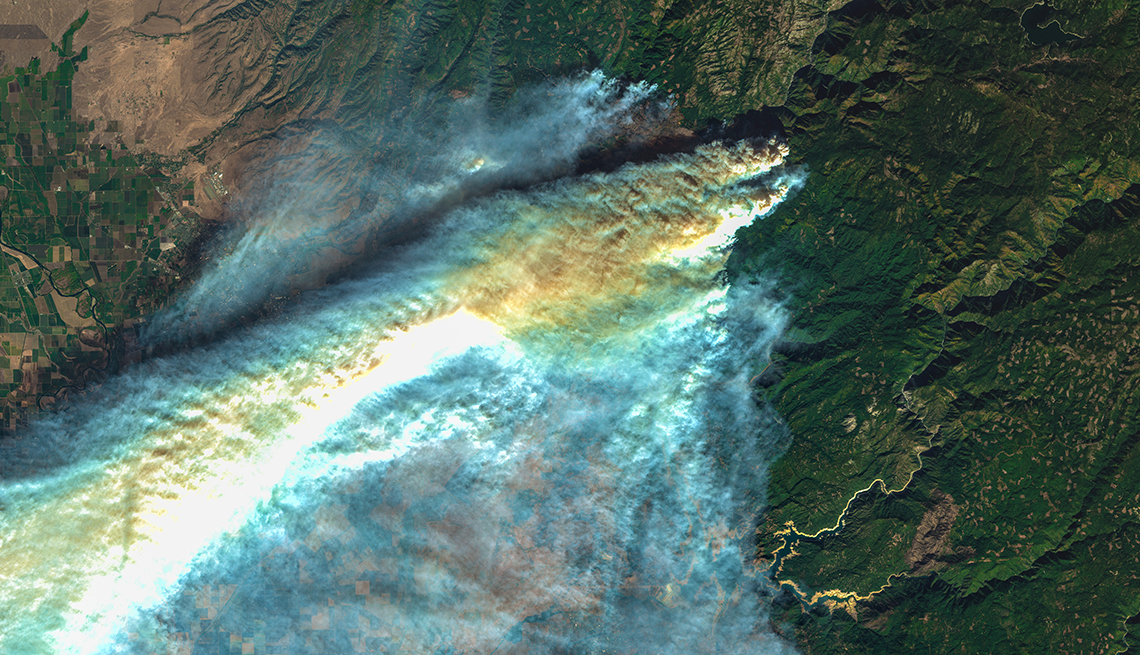

En español | PARADISE, California — A fire erupted just after dawn on a bone-dry autumn day in the Sierra Nevada foothills of Northern California. It was 6:33 a.m. on Nov. 8, 2018.

Some people were sleeping. Some were preparing for work. A 68-year-old woman was gathering her handwork — quilts and tole paintings — to sell at a local art fair.

The wildfire metamorphosed into a monster: a fast, cruel, unpredictable inferno that would demolish Paradise and breathe flames into towns nearby.

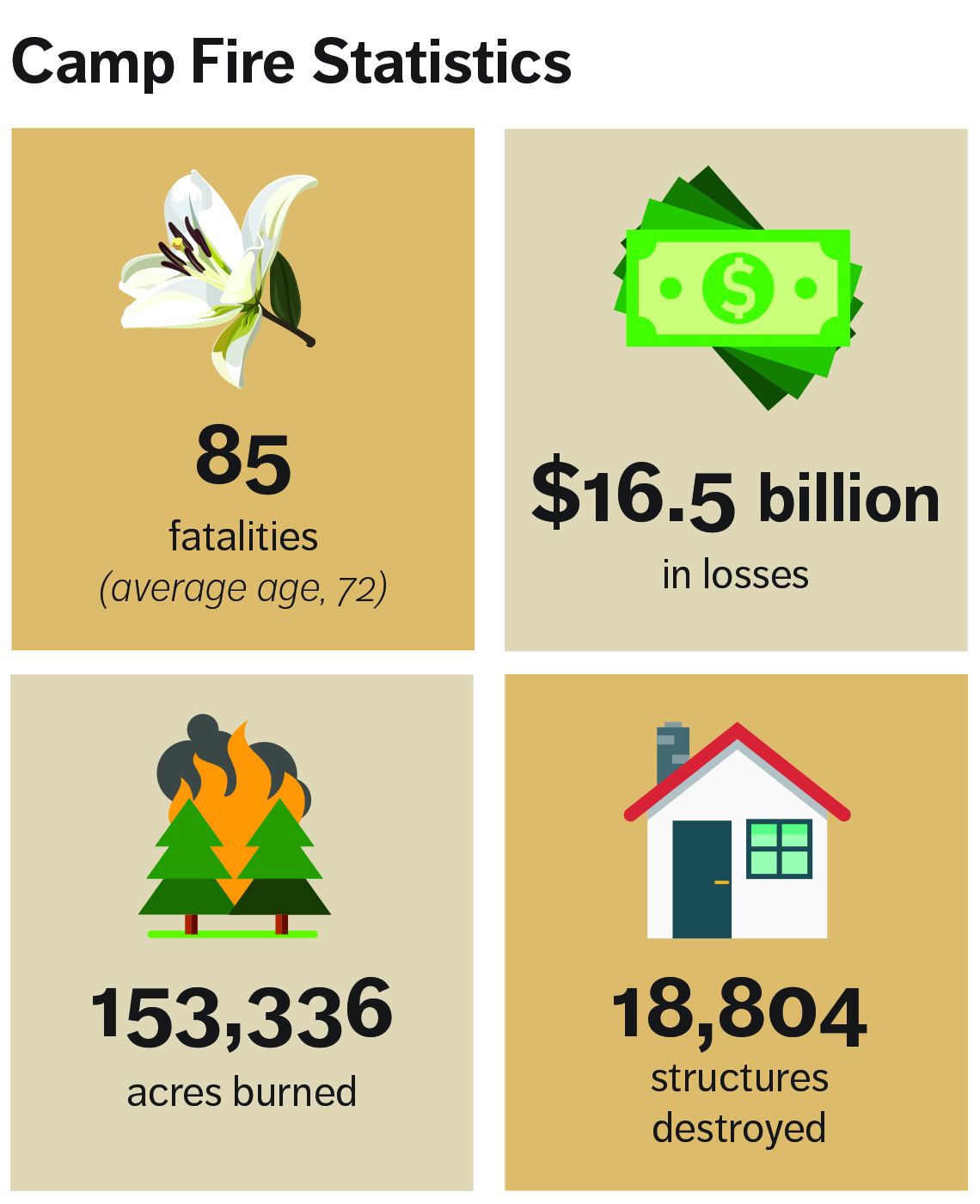

Paradise was a haven for retirees drawn to its tall conifers, sweeping canyon views, slow pace and affordability. The fire, which killed 85 people in Paradise and nearby towns, took a heavy toll on older Americans.

All but one of the dead have been identified. Among the 84 known victims, six were in their 50s, 22 in their 60s, 25 in their 70s, 18 in their 80s and seven over 90.

Rose Farrell, 99, Ethel Riggs, 96, and Vernice Regan, 95, were the oldest fatalities. Only six people killed were under the age of 50. Paradise, a rustic enclave with echoes of the Old West, was home to 26,000 residents before the cataclysm. Fewer than 4,000 are here now.

Seemed like the end of the world

“I thought it was Armageddon,” says Mary Rae Nieland, who planned to sell her wares at the art fair but found herself surrounded by flames, running for her life.

The fire sparked near Camp Creek Road, so the beast was christened the Camp Fire, a name suggestive of sing-a-longs and s’mores, not death and destruction.

Contained 17 days later, the wildfire was the worst ever to strike the state. It burned 153,336 acres — an area bigger than Chicago — and destroyed 18,804 structures in Butte County.

Estimated losses were $16.5 billion, making it the costliest natural catastrophe on the planet in 2018.

State fire officials say electrical transmission and distribution lines owned by PG&E sparked the Camp Fire. As the one-year anniversary of the fire neared, the electric utility turned off power to 738,000 homes and businesses in California, including the town of Paradise, for a few days last week. The same hot, dry and wind-whipped conditions that plagued the region a year ago led to concern that downed power lines could, again, spark a fire.

The Camp Fire, one of many recent, virulent fires to beleaguer Western states, underscores that in places prone to natural disaster, it is vital to develop an emergency-preparedness plan before catastrophe arrives at the front door.

That’s even more critical for older Americans, because people with physical and cognitive limitations are at greater risk of dying in a fire, according to the U.S. Fire Administration in Emmitsburg, Maryland.

Risk of fire death rises as you age

In the 10 years ending in 2017, 12,572 Americans age 65-plus died in fires; this age cohort was 2.6 times more likely to die in a fire than the population at large, statistics show. And the older you are, the greater your relative risk.

On that awful morning in Paradise, many things went badly. Some people never received an evacuation order. Some never opted in for automatic alerts delivered via cellphone calls and texts. Some of the dead reportedly slept through the fiery chaos. Others didn’t grasp how dire conditions were and then begged 911 dispatchers for help when it was too late, says Butte County Sheriff Kory Honea.

Officials say the death toll would have been worse if first responders, joined by fleeing residents, had not rescued countless people in conditions that Honea compares to the “fog of war.”

The dead perished in or near their homes or in vehicles during the traffic-choked evacuation, says Deputy Chief Scott McLean of Cal Fire, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

Fallen, burning trees and utility poles, burned cars and other hazards — and the colossal fire — made what on a normal day would have been a quick trip to Chico, in the valley below, into a hellish ordeal.

A grim verdict

McLean, 65, who lives in Chico, raced to Paradise that morning as the fire was barreling toward the town. By early afternoon he called his headquarters in Sacramento with an update: “The town’s gone.” It was the worst fire McLean has ever seen.

Paradise Mayor Jody Jones, 63, believes that more might have died if the town had not been as prepared as it was. That thousands of residents were evacuated safely from Paradise and next-door Magalia shows the town was ready, the mayor says.

“We didn’t have the perfect evacuation by any sense of the word, but we had an evacuation plan people knew about,” she says, estimating that 30,000 or more people made it safely “off the ridge.”

In the aftermath, survivors have scattered to states from Alabama to Wyoming.

After losing her home and belongings, Lynette Bellman, 53, followed her Mormon bishop's lead and left for Utah with her mother, 79, for a mobile home park the women had seen only on Skype. “Appreciate what you have,” Bellman cautions, “because when you go to bed at night, you don’t know what the next day will bring.”

Rebuilding Paradise, where an estimated 1,400 homes survived, is a work in progress. At the start of October, six new residences had been built. By year’s end, town officials expect to receive 500 building applications from people who plan to return.

Today, white crosses in a sun-drenched field of golden grass memorialize the 85 who died. They’ll be remembered during 85 seconds of silence on the fire’s anniversary.

A sculpture will be unveiled that day to symbolize Paradise’s starting over. It’s of the mythical bird that rose from the ashes, a phoenix. It’s metal and made from survivors’ house keys — for locks and doors they will never open again.

- |

- Photos