Your Money

WHAT YOU MUST KNOW ABOUT THE STOCK MARKET RIGHT NOW

More people are investing, but doing it on autopilot

Stocks are down! Now they’re up! Sharp swings in stock prices have increased in severity and frequency since the 1960s; the early 2020s have been especially volatile, according to DataTrek, a market research firm. Take just the past two years: The total U.S. stock market suffered a nail-biting 21 percent drop in 2022, only to be followed by a 24 percent surge last year.

Thanks largely to the proliferation of IRAs and 401(k) retirement plans, more Americans than ever have a portion of their wealth invested in the stock market. Understanding it and how it has changed can help you make wise decisions for your overall retirement plan. This may mean letting go of some old ideas and accepting the new. Here are answers to important questions.

Why do stock prices rise and fall so much these days?

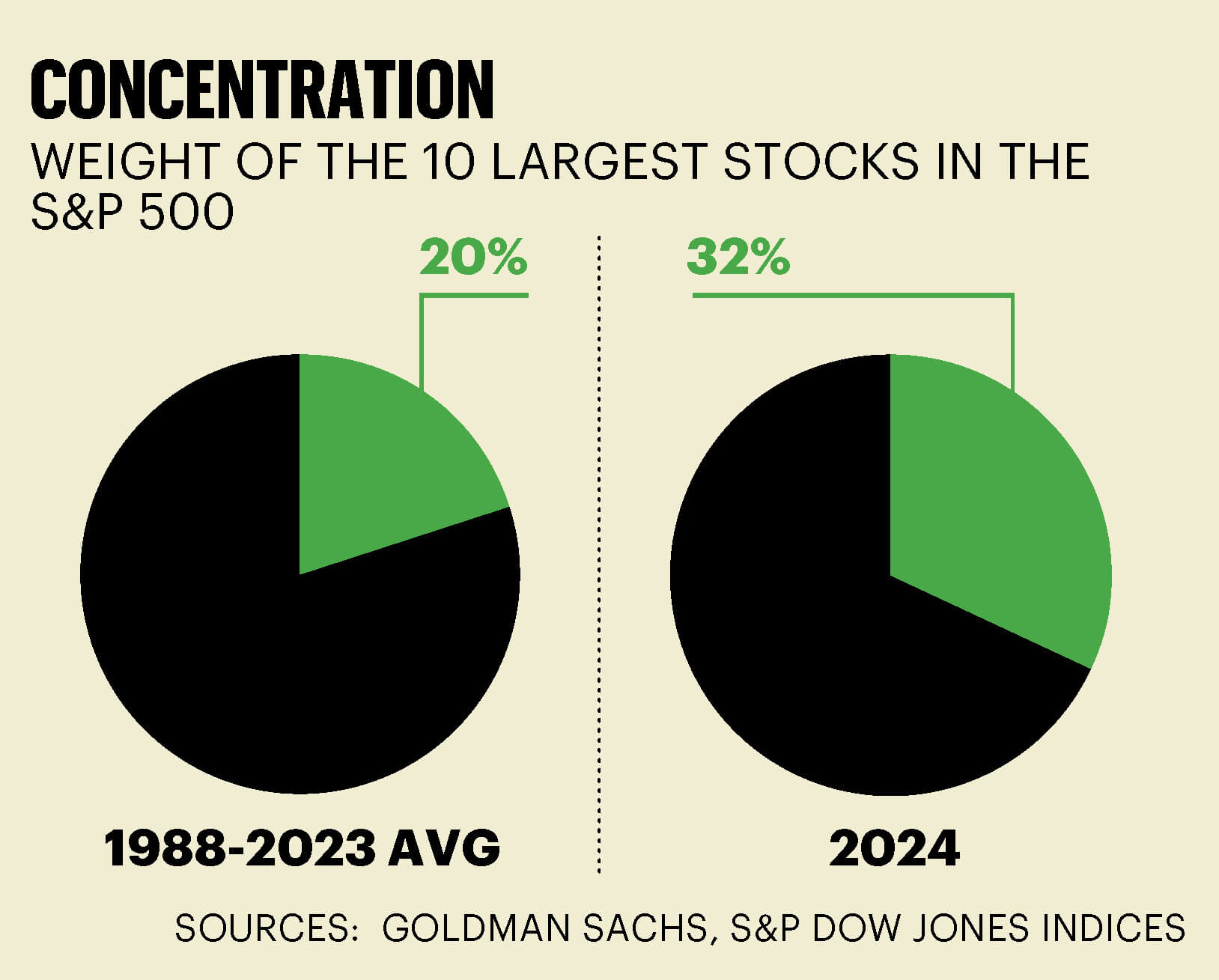

Economic uncertainty and geopolitical stresses, including wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, are major factors. High-speed computerized trading by investment professionals can make an up-and-down market even choppier. Another cause is rooted in the S&P 500, an index of 500 of the largest company stocks traded in the U.S. and the most commonly used proxy for the overall U.S. market. The 10 biggest stocks in the S&P 500—the ones whose fluctuations have the biggest effect on its movements up and down—make up a 32 percent share of that index, which is around the biggest share the top 10 have had over the past 35 years, according to Goldman Sachs. That can make the entire index sensitive to tremors in just these few stocks’ daily pricing.

I’ve heard that “meme” stocks can cause trading volatility. What are they?

These are stocks that attract an almost feverish following after being hyped on social media platforms. The phenomenon took off in the early days of the pandemic, when chatter among homebound investors on sites such as Reddit and Twitter (now X) latched on to particular stocks—often tech companies, and often for reasons having nothing to do with their realistic financial prospects.

Contributing to meme stocks’ rise are ever-declining fees for trading stocks. Fifty years ago, it cost at least $25 to buy or sell $1,000 worth of stock. Twenty years ago, you’d pay as little as $7. Nowadays, several brokerages, including Robinhood, E-Trade, Schwab and Fidelity, let you trade stocks for free.

Meme stocks have included video game retailer GameStop, movie theater chain AMC, and the eventually bankrupt home goods company Bed Bath & Beyond. “My advice when it comes to meme stocks, especially for long-term retirement investors, is to stay away,” says Ayako Yoshioka, senior portfolio manager at Wealth Enhancement Group in Los Angeles.

Are all my neighbors picking stocks?

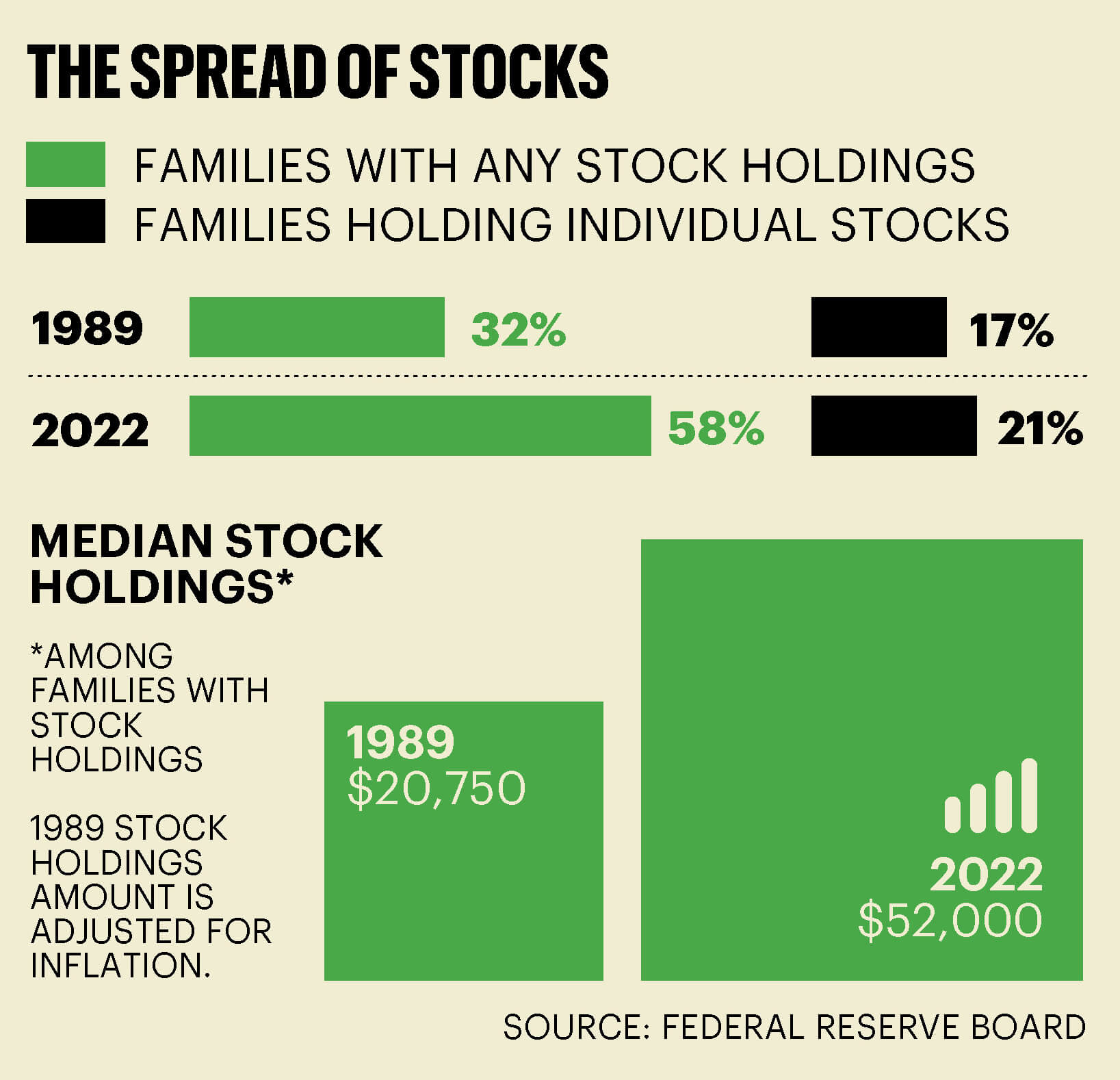

Not necessarily. The number of families holding individual stocks, according to the Federal Reserve, is 21 percent—not much different from 35 years ago. Yet the percentage of American families with savings in the stock market has nearly doubled, to 58 percent. Credit that to the rise in mutual funds and ETFs (exchange-traded funds)—professionally managed investment pools that may hold stock in dozens or hundreds or thousands of companies. Much of those holdings are in people’s retirement accounts, such as IRAs and 401(k)s.

So the people running those funds are picking stocks?

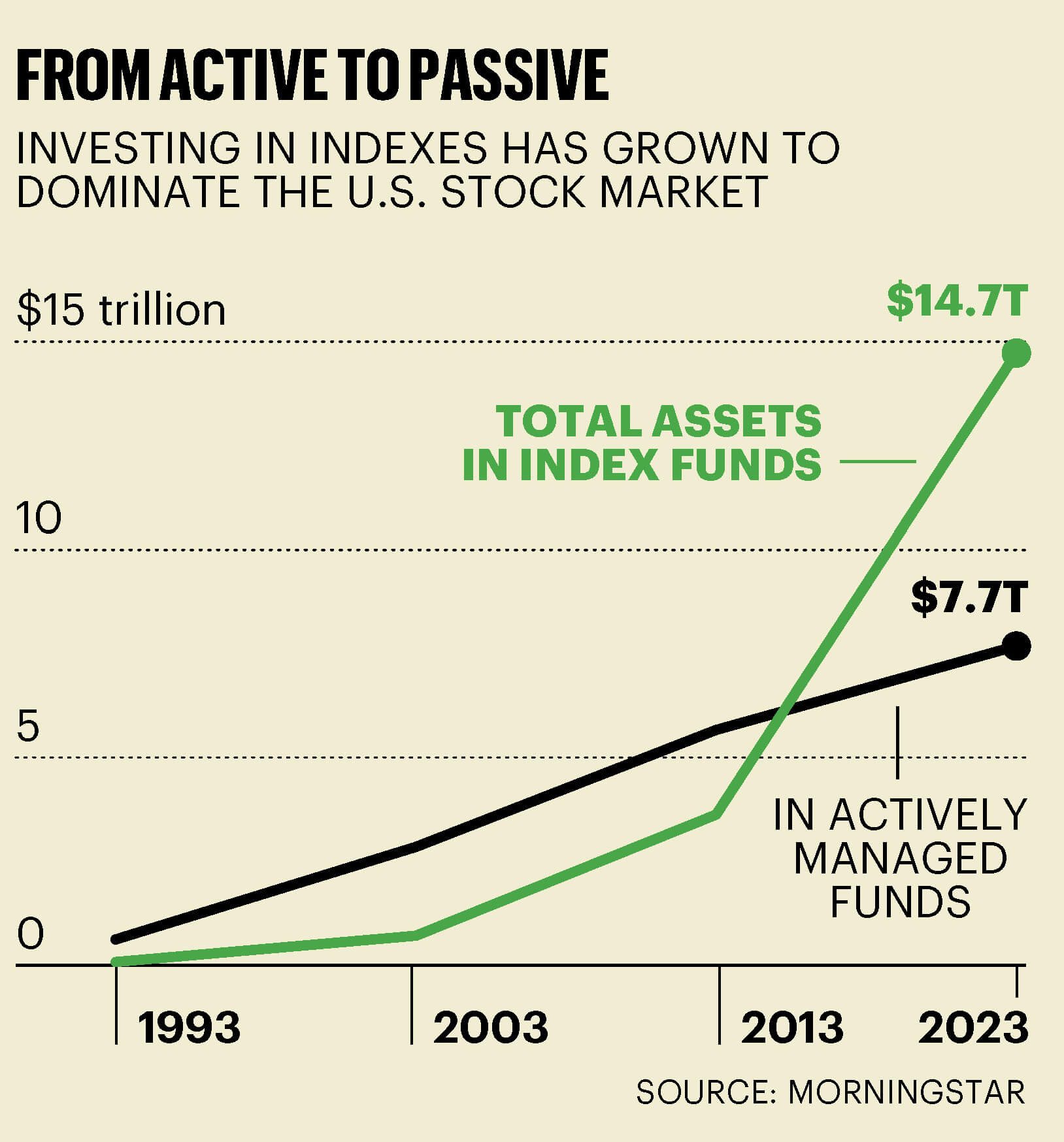

Less and less. Thirty years ago, nearly all stock funds were “actively managed,” meaning professional portfolio managers picked the stocks to buy and sell. Now the market is dominated by index funds, which simply mimic the holdings of a particular index and aim to deliver returns about equal to the index they track. That rise in index funds, often referred to as “passive” investments, is one element that diminishes the influence of an individual company’s profits and prospects on its stock price. “Now that assets in passive index funds and ETFs have surpassed assets in actively managed funds, the flows in and out of these passive funds and ETFs matter more than they used to,” Yoshioka says.

It’s no wonder that index funds are so popular. They’re cheap: Annual expenses charged by index funds average 50 cents for every $1,000 you invest, compared with $6.60 for actively managed funds. And index funds, on average, do better than stock-picking pros; as of mid-2023, the five-year returns of 87 percent of actively managed large-company U.S. stock funds failed to beat the S&P 500.

Didn’t people live off stock dividend payments in the past? Can I do that?

It’s getting harder than it used to be. Not all stocks pay cash dividends, which are a portion of profits, usually paid to shareholders quarterly. And dividend yields—a stock’s annual per-share total dividend expressed as a percentage of the share price—have decreased. The current dividend yield of all the stocks in the S&P 500 is 1.47 percent. That’s down from the 1.8 percent average over the past 25 years, and the 3.7 percent average over the 25 years prior to that. A dividend-focused mutual fund or ETF may yield more, though often at the expense of price appreciation. The Dow Jones U.S. Dividend 100 Index, for example, yielded 3.6 percent as of February’s end, but its total return—the gains from dividends combined with the changes in stock price—has lagged the S&P 500’s over the past decade.

Still, dividend-paying stocks play an important role in portfolios. “Dividend stocks don’t go up as much during the good times, but they don’t go down as much in the bad times,” says Howard Silverblatt, senior index analyst at S&P Dow Jones Indices.

How will the market do this year?

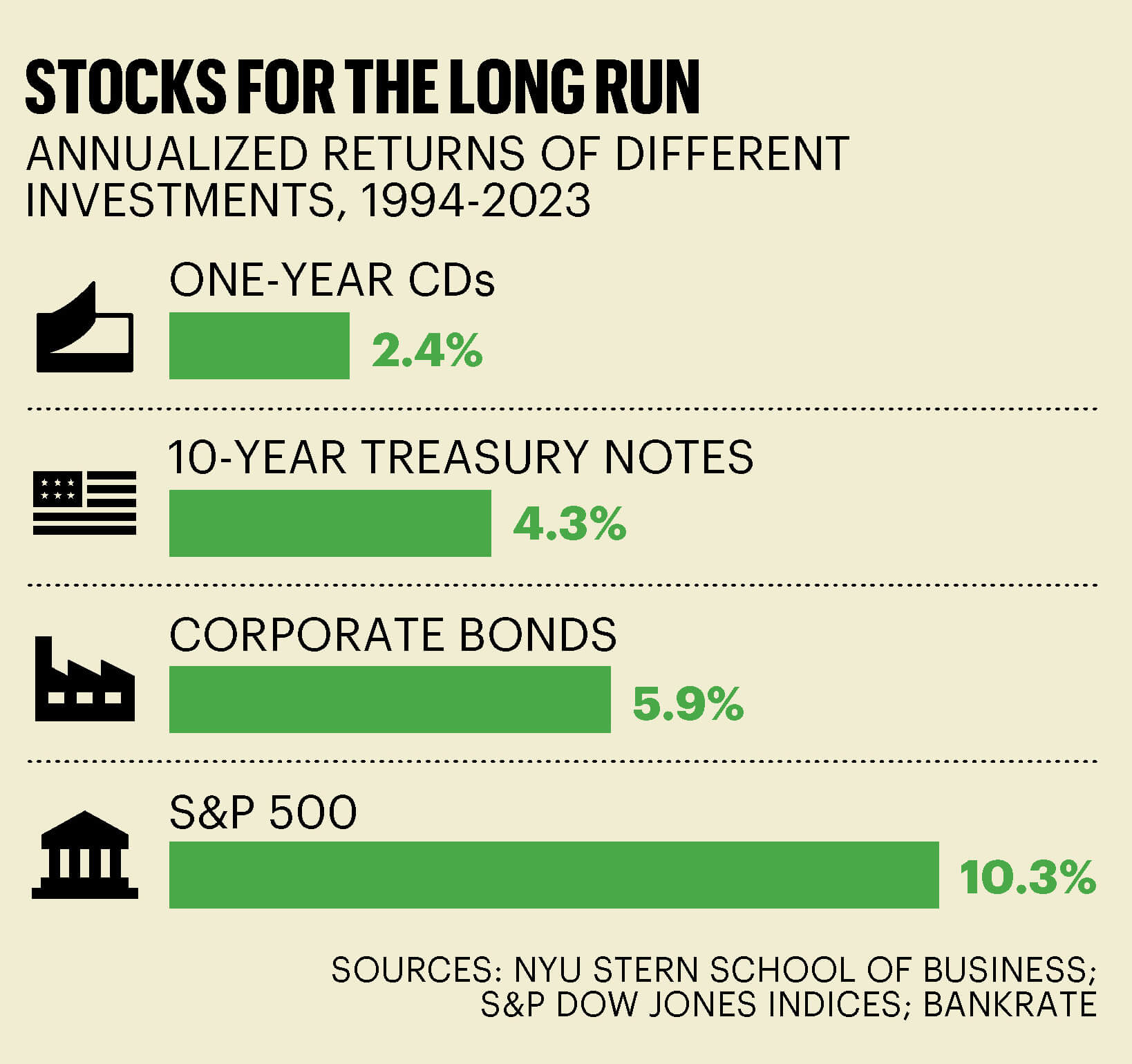

Nobody knows, and don’t believe anyone who says they do. Every year, Wall Street firms issue predictions of how the stock market will do, and every year they’re wrong. In 2022, forecasters predicted, on average, that the S&P 500 would rise 3.9 percent; instead, that important subset of the market plummeted 19.4 percent. Last year, the outlook was for a 6.2 percent gain, but the S&P 500 galloped ahead, ending the year up 24.2 percent. “Rather than focusing on forecasts, it’s better to take a long-term view and remember that stocks tend to outperform other asset classes over time,” says Paul Hickey, cofounder of Bespoke Investment Group in Harrison, New York.

It seems so uncertain. Should I bother with stocks at all?

Stocks give you the best chance of having your savings grow faster than the inflation rate over the long run. (They don’t always grow faster in the short term.) If you keep all your money in cash, for example, inflation will cause those dollars to buy you less and less over time. “Over longer holding periods, stocks have had higher real, inflation-adjusted returns than lower-market-risk investments like money markets and bonds,” says Fran Kinniry, head of the Investment Advisory Research Center at Vanguard in Malvern, Pennsylvania. Most investors, he says, need a mix of stocks, bonds and money market funds that balance the risk of losing purchasing power against the risk of a declining market.

So if I invest in stocks, how should I do it?

Broad-based index funds, available from any major brokerage firm and usually through your workplace retirement plan, offer the simplest approach. Buying individual stocks is highly risky. “If you buy five or 10 stocks and a few tank, it will have a huge impact on the value of your portfolio,” says Matt McGrath, managing partner at Evensky & Katz/Foldes Wealth Management in Coral Gables, Florida. If you still want to add individual stocks, be sure you are using money you can afford to lose, he says.

Karen Hube is a veteran financial writer and a contributing editor for Barron’s.