Your Life

UNSUNG HEROES OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

Along with legendary champions, thousands sacrificed during the era of change. Here are a few of their stories

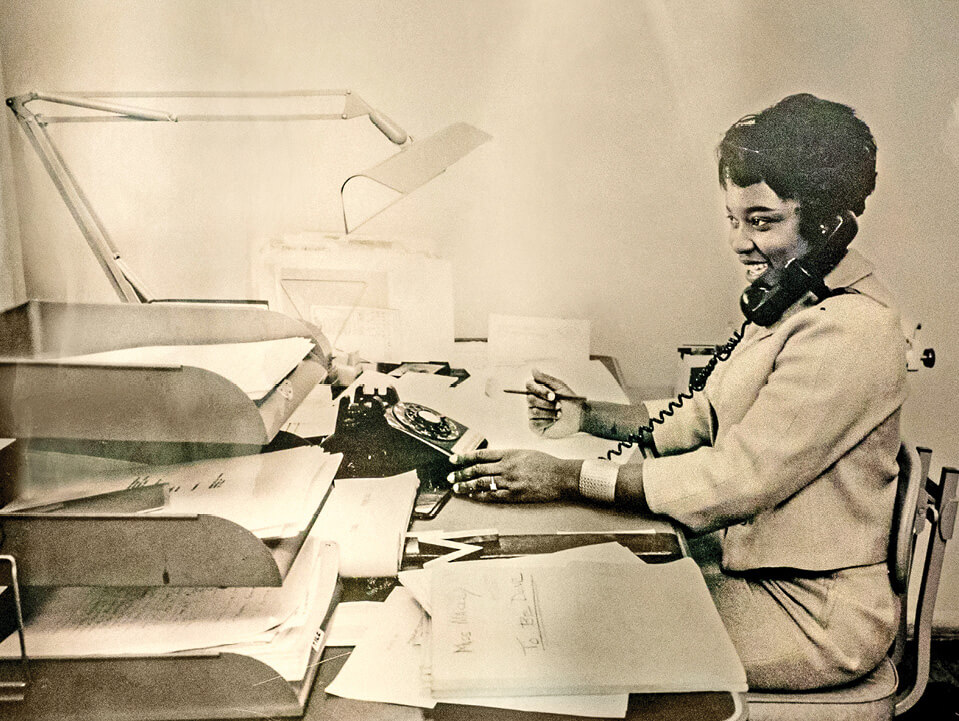

Willie Pearl Mackey King in her church in Silver Spring, Maryland

Martin Luther King Jr. Rosa Parks. Medgar Evers. John Lewis. These names ring through history as leaders of the vast, sprawling events that constituted the Civil Rights Movement in which African Americans struggled for equality during the 1950s, 1960s and beyond. But the movement could not have succeeded without thousands of people of all races making important, if often overlooked, contributions, and without millions of people moved by their efforts deciding that it was time to do the right thing.

For Black History Month, we went in search of those men and women who did their part to change the history of America, without seeking fame or reward, simply because they saw the need to become part of the solution.

Here are their stories.

Willie Pearl Mackey King on the Birmingham Jail Letter

82, living in Montgomery County, Maryland

King worked from 1962 to 1966 as a member of Martin Luther King Jr.’s executive staff.

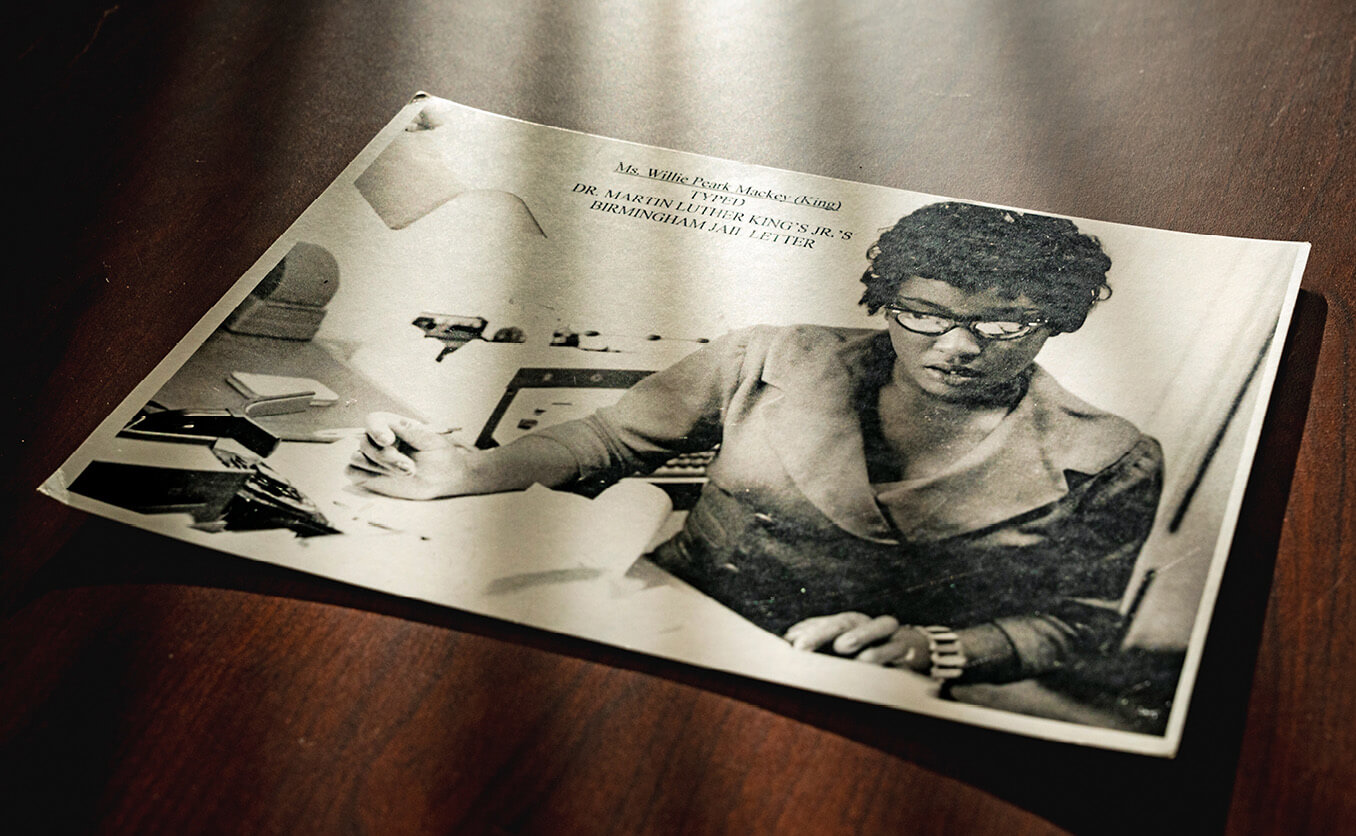

King typing the Birmingham jail letter

WHERE I LIVED, in Atlanta in 1962, the landlady rented her extra bedrooms to college students and working young ladies. Dorothy Cotton lived on the first floor. [Cotton is known as a pillar of the Civil Rights Movement.] One day she asked if I was looking for work. I had never worked in an office. Dorothy gave me an address and said, “You should go here and apply.” That is how I got hired at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

They put me at the receptionist desk, and I started reading brochures about this place where I was working. I had never heard of “civil rights” before. Then, one day, this gentleman came in and greeted me, asking me about my church and my family. I realized that this was the man in the brochures! He was in charge of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and his name was Martin Luther King Jr.

Dr. King asked me if I would go with him on certain trips. I was elated! In December of 1962, I went with Dr. King to Birmingham, to organize a “people-to-people tour” of the state of Alabama. We visited towns all over the state, and this is how the Birmingham movement got started.

This was to be nonviolent protest in the heart of Jim Crow. The FBI told Dr. King, “There are credible threats against your life. We cannot guarantee your safety.” Well, Dr. King called us together. He said, “If you decide you don’t want to go on this trip, that it’s too dangerous, I will not be offended. Because we could be killed.” I looked around, thinking it would be canceled. But no one else said no. I went off and did my crying, then came back and said, “I’m going.”

Willie Pearl Mackey in 1963

On Good Friday in 1962, after the protests in Birmingham began, Dr. King was arrested. A group of eight ministers wrote an article, “A Call to Unity,” saying Dr. King was an outsider and urging locals not to participate in what he was doing. Dr. King decided that he was going to write an answer. He was in jail, and he asked the jailers for pen and paper. They said, “You’re not in a library! You don’t get anything to write with.”

He wrote on the edges of newspaper, on toilet paper, on sandwich bags. His attorney Clarence Jones hid the scraps under his suit jacket and slipped them out of the jail. We had to put together this jigsaw puzzle. We were on the floor, trying to figure it out, Scotch-taping things together. Dr. King’s handwriting was not the best. The lighting was terrible in his jail cell.

That is how we developed the “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” When we released it, no one paid attention at first. Only when Bull Connor [the city’s commissioner of public safety] ordered fire hoses and dogs onto the demonstrators in Birmingham’s Kelly Ingram Park did we start getting requests for the “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” I could not mimeograph enough copies. [The letter became one of the most important documents of the civil rights era.]

If people read that letter today, they will understand what Dr. King was doing in Birmingham, and why he was fighting so hard for civil rights. In my opinion, none of his speeches or writings will give you a clearer vision of his mission.

My whole career was helping people. That was instilled in me by Dr. King and others that I worked with so closely. I can’t think of a better way to spend a life than helping people.

Charles Person on the Freedom Riders

81, living in Atlanta

Civil rights activist, the youngest member of the original Freedom Riders. Later, a Vietnam veteran and the author of Buses Are a Comin’

Charles Person

MY DAD WAS a patriotic veteran of the Second World War. He was optimistic that change would come for Black people. “This is our country too.” That’s what my dad preached.

My journey began when, as a high school senior in Atlanta, I applied to Morehouse College in Atlanta and was accepted.

When I got to campus in 1960, the sit-in movement was beginning. I was there every day. The idea was to enter a restaurant, sit at the counter and shut the restaurant down, because we knew, as Black people, we wouldn’t be served. Ultimately, I was arrested with others.

In 1961, the Congress of Racial Equality organized the first Freedom Ride. The idea was to challenge the nonenforcement of the Supreme Court decisions that ruled that segregation on interstate buses and in bus terminals was unconstitutional. The Southern states were ignoring these decisions. Our goal was to ride the bus south and sit where they said we couldn’t. This was not civil disobedience. The law was on our side.

“ A group of men came toward us ... the beatings started.”

I was 18 and needed a parent’s signature. Dad approved. Mom was reluctant. But I went. The first Freedom Ride bus left Washington, D.C., on May 4, 1961. Aboard was a mix of Black and white activists, including future Congressman John Lewis. I was the youngest Freedom Rider on that first trip.

We were well-groomed, because how we presented ourselves was important. Each night, we stayed with members of congregations who fed us. We switched buses each day for safety. We were ordinary people, trying to do things to make our lives extraordinary.

People taunted us all the way to Alabama. When we got to Anniston, a group of men boarded the bus and came toward us. That is when the beatings started. In Birmingham, the next stop, a mob was waiting when we exited the bus. My fellow Freedom Rider James Peck went down almost immediately. I maintained my balance but had my scalp opened. I got away from the crowds and, as luck would have it, a city bus came by. I got on, and the driver had sympathy; he took me to a safe place. He said, “If you go across the tracks, there will be someone there to help you.”

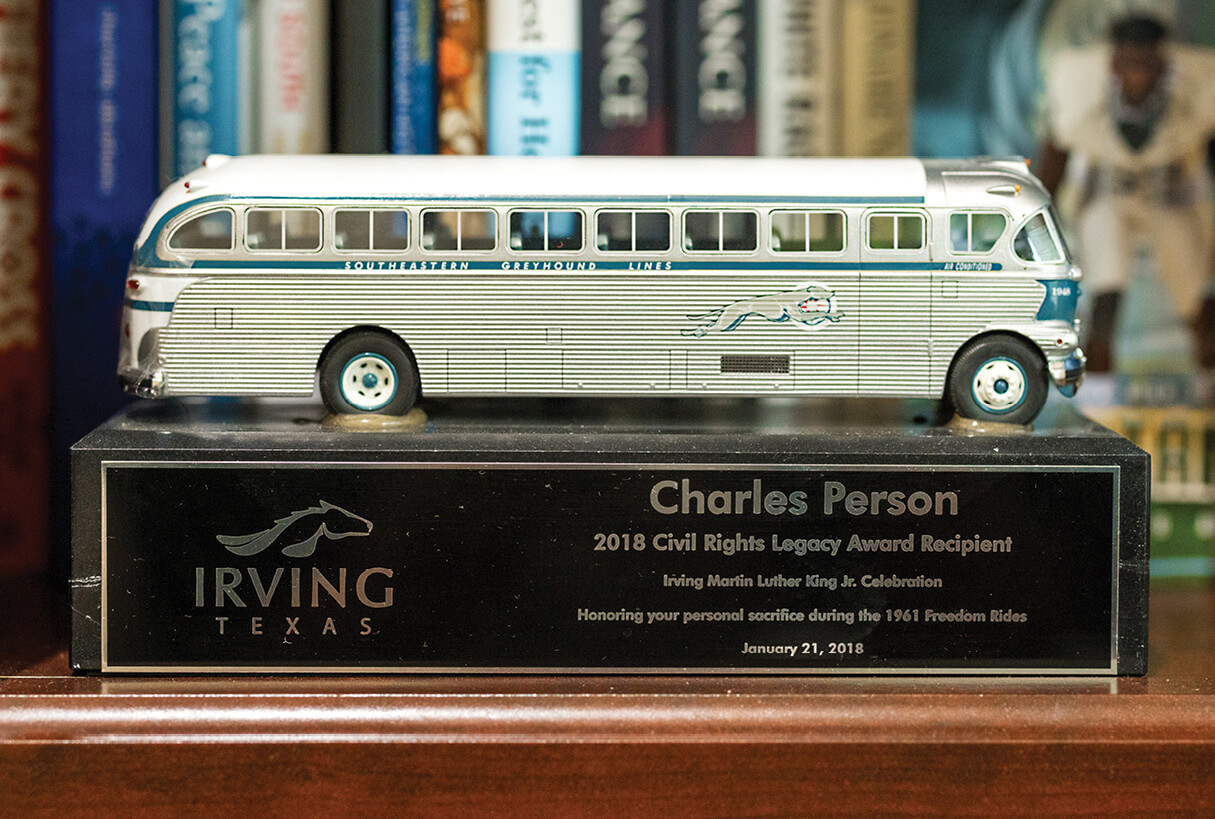

Person’s 2018 Civil Rights Legacy Award for his sacrifice during the 1961 Freedom Ride

I ended up in a church, where a nurse put a bandage on my head that pulled my scalp together. [The beatings made national news as a pivotal event in the civil rights struggle.] Using photographs, the FBI identified the men who beat us. I thought it was a slam-dunk case. But there was no way an all-white jury in the South would convict white men for beating up a Black person.

I made the entire ride to New Orleans, and when I got back to Atlanta, my mom thought I’d be killed if I stayed in the Civil Rights Movement. Like my father, I chose to serve. I entered the Marine Corps and went to Vietnam. I was exposed to Agent Orange and have cancer today.

Whenever I have the chance to speak to young people, I tell them they can change the world. I hope they listen to anyone who tells them they have the power to make the world a better place.

Fred Gray on the Montgomery Bus Protest

93, living in Tuskegee, Alabama

A preacher and a civil rights attorney who argued some of the most important cases regarding race in American history

Attorney Fred Gray in Tuskegee, Alabama

WHEN I WAS growing up, there were two professions a Black man could take up: a preacher or a teacher. I studied to become a preacher in Nashville, Tennessee, and when I returned to my home state of Alabama, I enrolled at the Alabama State College for Negroes (now Alabama State University). There were serious problems with how Black people were treated on the buses, including one man who had been killed. E.D. Nixon, a Black leader and president of the local NAACP branch, told me they needed lawyers and didn’t know any. So when I graduated college, I enrolled at Case Western Reserve [then Western Reserve] University law school in Cleveland, Ohio. I passed the Alabama and Ohio Bar exams in the summer of 1954.

Six months later, on March 2, 1955, a 15-year-old girl named Claudette Colvin was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a public bus to a white person. Claudette lived in an area in the northern part of Montgomery. There were two or three streets of Black families surrounded by whites. The Black schoolkids had to take two buses to get to Booker T. Washington High School.

On the day Claudette was arrested, the students had been let out early from school because of a teachers’ meeting. When they got downtown, a lot of white people were getting on the bus and they asked Claudette to get up from her seat. She was not sitting in what was called the white section, and so she told the bus driver she was not going to get up. She was arrested, and I agreed to represent her in juvenile court. Claudette’s was my first civil rights case. The judge was very polite, but he still found her a delinquent.

Nine months later, Rosa Parks did the same thing. I had known Mrs. Parks from the time I was an undergraduate at Alabama State. When I opened my law office in late September of 1954 to the day of her arrest on Dec. 1, 1955, she would come to my office and talk about problems, about how even after the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision in 1954, no schools in Alabama were desegregated.

Gray after winning election to the Alabama House of Representatives, 1970

We had talked about how a person should conduct themselves if they were asked to give up a seat on a bus. I had gotten the impression that, if the opportunity presented itself, she would not give up her seat. Which is what she did. She retained me to represent her.

I met with Edgar Nixon of the NAACP and Jo Ann Robinson, an instructor at Alabama State University, who was the president of the Women’s Political Council, an organization in Montgomery to help Blacks get registered to vote and to generally improve conditions. At her house, we planned the Montgomery bus boycott. [Black people stopped riding buses, threatening to financially cripple the city’s transportation system.]

Jo Ann Robinson said, “We will need a spokesman. My pastor, Martin Luther King, hasn’t been here in Montgomery long, but he can move people with words. We can get him to be the spokesman.” I had never met Dr. King. Few knew who he was at that time. He was selected to be the spokesman, and I to do the legal work.

We held a meeting at Holt Street Baptist Church. When the people heard Dr. King speak, we were convinced that important things were about to happen. And when the buses rolled on Monday morning, very few Blacks were on them. Dr. King and I were in contact almost on a day-to-day basis for the 382 days of the bus boycott. Only we did not call it a boycott because it wasn’t a boycott. We called it a protest. During that time, the world came to know his name.

Three months after the Montgomery bus protest began, Alabama indicted 89 persons. The prosecutors then decided that instead of trying 89 cases, they would select one, and of course, they selected Dr. King. I had the responsibility of getting a legal team together. We tried that case for four days. We were able to get Black people to describe how they had been mistreated on the buses, including the wife of a man who had been killed. Notwithstanding, the judge found Dr. King guilty.

For the rest of my life, I have fought to destroy everything segregated I could find. I have fought for education rights, for Black voting rights. Inequality and the struggle for equal justice continues.

I am now 93 years old and still fighting.

A.J. Baime is the author of White Lies: The Double Life of Walter F. White and America’s Darkest Secret.

Find out about more civil rights heroes and how they triumphed at aarp.org/CivilRights