Cover Story

PHOTOGRAPHY BY ANDRE RUCKER

Lingering inflation. Persistently high interest rates. Conflicts abroad, mixed economic predictions at home and a looming presidential election. These are particularly confusing times for economic prognosticators, let alone all the rest of us trying to stretch a buck. But there’s a safe path through the challenges of the year ahead. In these pages you’ll find a primer to today’s economic situation and steps you can take right now to safeguard your money during these confusing times.

THE ECONOMY RIGHT NOW, EXPLAINED

The numbers say we’re doing well financially—and badly too. We get pros to sort things out

Q: Is the U.S. economy in good or bad shape?

In many respects, it’s legitimately doing well. Unemployment, at 3.7 percent in November, isn’t too far from 21st-century lows. The inflation rate of 3.1 percent in November is way down from its 9.1 percent high in June 2022.

These trends surprised the many economists who predicted a recession by the second half of 2023 after two quarters of slowing growth. “Typically, when you have higher inflation and interest rates, you land in a recession,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics. But last year, the economy found another gear. Thanks in large part to continued strong buying by U.S. consumers, the gross domestic product—a measure of all economic activity in America—grew 4.9 percent in the third quarter of 2023, the strongest period in almost two years.

The numbers hint at a rosy picture for individuals too. Though 2022 was a miserable year for investors, 2023 saw a nice recovery for many people’s retirement accounts, and stock indexes are higher than before the pandemic. Home values are also strong. For people who are employed, wages are up and post-pandemic job flexibility has elevated satisfaction at work.

Q: So why do I feel stressed about money?

The inflation rate has improved, but that doesn’t mean prices are rolling back to where they were before the inflation spike; they’re just climbing at a slower pace. Consumers are still paying considerably more for goods and services than they were two years ago. That takes a toll: When a burger you used to buy for $5 now costs $8, or your $1,500-a-month apartment now costs you $1,850, you get skeptical about the economy and more worried about the future. The U.S. personal savings rate has been sinking steadily. This was expected after pandemic relief dried up, but its 3.8 percent level last October was well below the long-term average of over 8 percent.

“Everyone is still feeling the pinch after two years of inflation,” says Adrian Cronje, chief executive officer of Balentine, an Atlanta wealth management firm. “For retirees, it’s especially hard, because they are questioning whether the money they have saved for retirement is going to be enough.” According to the Conference Board’s long-running survey of people’s feelings about their current financial situation and expectations, confidence among consumers 55 and older hasn’t recovered from a sharp decline that began in the summer of 2021.

Rising interest rates have made auto loans and credit card debt more burdensome. Thirty-year fixed mortgage rates hit a roughly 20-year high of around 8 percent last fall, compared with the median 3.5 percent for existing mortgages. That leaves many folks feeling stuck—unwilling or unable to buy or sell.

Q: Why does it cost so much to borrow money?

It starts with the Federal Reserve, the nation’s central bank. The Fed’s job is to strike a balance between too much economic growth, which drives up inflation, and too little growth, which can trigger a recession and cause widespread unemployment. A key tool for the Fed is what’s known as the federal funds rate, which is the interest rate banks charge one another for short-term overnight loans. To kick-start a shaky economy, the Fed can lower the federal funds rate to make it less expensive to borrow money. That lets banks lend at lower rates, better enabling consumers and businesses to make big-ticket purchases. This is exactly what the Fed did during the first two years of the pandemic to keep the economy moving.

The inflation rate has improved, but that doesn’t mean prices are rolling back.

On the other hand, when economic growth and demand increase, prices begin to inflate. To rein that in, the Fed can raise interest rates, making borrowing expensive and putting the brakes on economic activity. That’s what the Fed did starting in 2022, when inflation spiked due to a number of factors—among them a rise in consumer demand, supply-chain bottlenecks and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

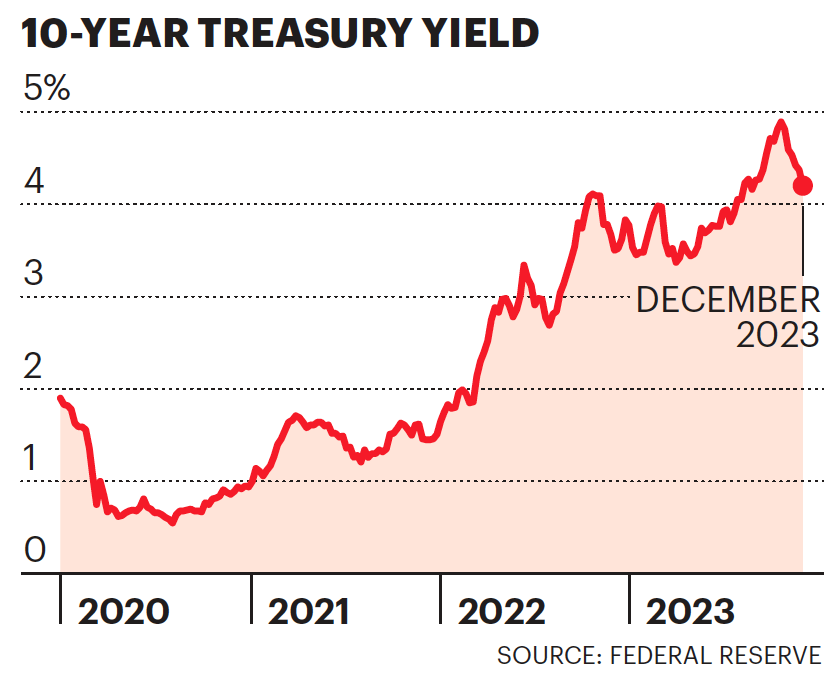

Yields on these ultra-safe Treasury notes are up from their 2020 half-century lows. That’s been good for savers, but not for homebuyers.

This recent inflation has proven challenging to tame, so the Fed continued to raise short-term rates. In a domino effect, banks passed along their higher borrowing costs by raising interest rates on debt such as credit card balances and auto loans.

Q: Those are short-term rates. Why are long-term rates on mortgages so high?

Interest rates on mortgages are generally tied to yields on 10-year Treasury notes, which were under 1 percent for much of 2020 but were over 4 percent in early December.

There’s an additional reason: After banks originate mortgages, they sell them to investors, who start receiving the mortgage payments. If mortgage rates fall, homeowners will likely prepay high-rate mortgages to lock in lower rates, reducing income for the investors holding those mortgages. Because today’s rates have so far to fall, it’s likely that homeowners will jump at the chance to refinance and prepay their mortgages someday. To attract investors concerned about that possibility, banks have raised mortgage rates even higher, Zandi says: “Investors need to get compensated for the risk they’re taking.”

Q: What further dangers do we face?

A recession and a prolonged stock market downturn are real possibilities. The most likely negative scenario, Zandi says, is a slowdown in consumer spending, which is the biggest engine powering the U.S. economy. If strife in the Middle East disrupts the oil supply and drives up gas prices, Americans will probably rein in their spending, he says: “There’s nothing more discouraging to consumers than having to pay a lot more at the gasoline pump.”

That’s only one possibility. Recession triggers often come out of nowhere—the pandemic being a prime example of that.

Q: What is the best outcome from here?

The best-case scenario is for a so-called soft landing: The Fed succeeds at rolling back inflation without causing a significant increase in unemployment or negative economic growth. Also helpful would be a resolution of current international conflicts and tensions, along with the avoidance of new ones, so the world’s economy can also get back on its feet and not hinder our own.

Eventually, a recession is likely, because recessions are inevitably part of the boom-and-bust economic cycle, says Mark Hamrick, senior economic analyst at Bankrate. A realistic hope, he says, would be for a mild recession well down the road—one that wouldn’t hurt employment badly.

Q: What are the best moves for me now?

First, minimize the harm caused by high-interest-rate debt. Start with your credit card balance. Credit card rates surged to more than 21 percent last fall. Your ultimate goal is to pay off your full balance each month so you pay no interest on your charges. To get there, pay more than usual each month and consider rolling your balance to a lower-rate card, Hamrick says.

Second, make higher interest rates work for you. Put cash you might need in the short term to work in safe, high-yield investments such as Treasury bills or money market accounts, says Gretchen Hollstein, a senior adviser at Litman Gregory Wealth Management in the San Francisco Bay area: “Unlike in recent years, you don’t have to take a lot of risk to get a decent return.”

Karen Hube is a veteran financial writer and a contributing editor for Barron’s.