Cover Story

THE WAR ON CHRONIC PAIN

INSTEAD OF A SINGLE CURE, RESEARCHERS ARE NOW LOOKING FOR A MULTIPRONGED APPROACH TO MANAGING EVERYDAY ACHES

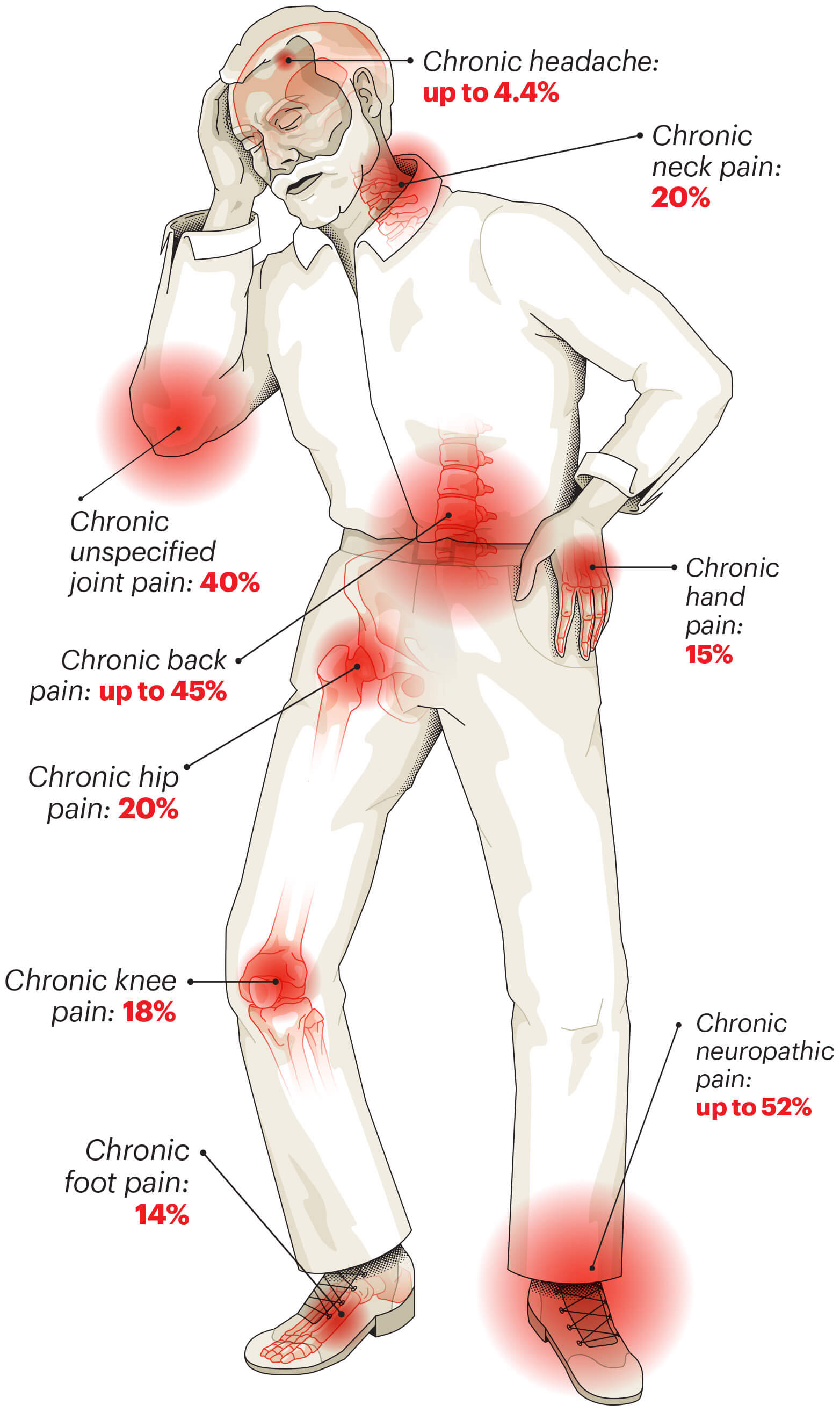

PAIN POINTS

For older adults, chronic pain can strike anywhere from the head to the toes. Here’s where it’s commonly found in those 65-plus.

Source: Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 2020

Chances are, right now, you’re in some sort of pain.

Maybe your back aches, or arthritis is hurting your hands or knee pain is hobbling your walk. Maybe you’re dealing with something even more intense—lingering, life-altering pain from diabetes or cancer.

These are all forms of chronic pain, a type that persists longer than three to six months and rears its ugly head most every day. Chronic pain strikes in many ways—musculoskeletal pain from gout or lingering injuries, inflammatory pain from autoimmune disorders, neuropathic pain from impinged or degenerative nerves, even pain that’s linked to psychological issues. And it hits older adults especially hard.

“As we get older, pain becomes a part of our life,” says Michael Ashburn, M.D., director of pain medicine at Penn Medicine in Philadelphia. With each passing year, the risk of chronic pain grows higher, affecting 26 percent of adults ages 45 to 64 and 31 percent of those 65-plus. Chronic pain does more than deliver unrelenting aches, stiffness and tenderness: It shrinks your life, too. Data from the National Center for Health Statistics finds that more than 1 in 10 adults 65 and older say they have pain that limits their life most days or all the time.

Yet most of the news we’ve gotten about pain management over the past decade has been disappointing, to say the least. Our attempts to treat chronic pain with medication have led to an opioid abuse epidemic so severe that overdoses are now among the leading causes of death for adults ages 50 to 70.

But in the wake of all this despair, there may be real hope. Researchers are discovering new ways to understand our pain and developing novel treatments—including powerful nondrug options—that may help you live more comfortably.

WHAT IS PAIN?

Touch a hot pan or stub your toe, and your body lets you know. Climbing stairs, that telltale crunch makes you slow down.

“Pain is something we experience pretty much on a daily basis, yet it remains a very complex and mysterious phenomenon,” says Haider Warraich, M.D., of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and author of The Song of Our Scars. “Pain is an alarm bell that goes off in our body to get our attention so that whatever we’re doing to cause the pain is immediately rectified. But one of the biggest mistakes we make is that we think of pain as purely physical sensations.”

It makes sense that your body wants you to take action to stop the pain. Pain turns more complex when it becomes chronic, Warraich says. “Chronic pain is a combination of a physical sensation and an emotion that your body feels,” he says. Meaning, there’s more than just physical damage; it’s emotional, social and psychological too.

“The assumption that what works for acute pain will also work for chronic pain is the root cause of the mistakes we’ve made in medicine and as a society when it comes to the treatment of pain,” Warraich explains. That’s why attempts to throw opioids and other potent drugs at chronic pain conditions have failed spectacularly.

Understanding pain and appreciating its complexity has opened doors for new treatments. And that’s why we’re in such a better place to treat it.

YOUR BRAIN ON PAIN

Pain isn’t simply a signal that the body zips to the brain that registers as ouch. That’s an outdated belief, says Tor Wager, distinguished professor of psychological and brain sciences at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. Pain is more of a guess made by your brain in reaction to a physical stimulus: My body is under threat, so what should I be feeling now? “It’s about much more than what’s coming in from your skin and joints. Your brain interprets these sensations in the context of other factors, including your memories, thoughts and feelings,” Wager explains.

When you’re injured, your body becomes hypersensitive to pain. This serves a purpose: You avoid walking on a twisted ankle, for example. As you heal, you gradually move more, and those sensations abate, until you feel normal walking on your ankle again. With chronic pain, however, your attention to these signals becomes amplified, and you can get stuck in a cycle of pain even after your body has healed, Wager says. That doesn’t mean that your pain isn’t real or wasn’t caused by a legitimate injury or illness that kick-started the process. But your body and brain can’t simply transition back, and your nerves remain oversensitive to stimuli, creating lingering pain.

If left to simmer, chronic pain can easily spiral, causing depression and anxiety, sleep deprivation, social isolation, and even economic and financial burden, says Salahadin Abdi, M.D., a pain specialist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

The key to pain treatment—and what makes it so tricky—is figuring out what’s contributing to and driving your pain. “For any given person, figuring out the mix of those different things can be complex,” Wager says. It’s not all in your spine or knee joint. And it’s not all in your mind, either. Discovering your personal pain quotient—your tolerance and threshold—is the first step to healing.

BUILDING YOUR PAIN MANAGEMENT PLAN

With age, pain can become more widespread and complex. “Three-quarters of older patients have pain in multiple places. It’s not just a matter of asking ‘Where do you hurt?’ but ‘Where do you hurt the most, and which pain is bothering you the most today?’ ” Ashburn says.

The answers to those questions will inform how to tackle your pain. Before a doctor’s appointment, be prepared to discuss:

▶︎ When did the pain first come on?

▶︎ Where is it located?

▶︎ What time of day does the pain come on?

▶︎ What does it feel like? (Dull, aching, shooting, burning)

▶︎ What makes the pain better? (Positions, time of day, meds)

▶︎ What makes the pain worse? (Stress, movement, lack of movement)

▶︎ What activities have you had to curtail?

“The goal of treatment is to reduce—not necessarily cure completely—your pain as much as possible, so you have a better quality of life and can do what you normally do,” Abdi says. If you haven’t already, ask your doctor to connect you with a pain physician in your hospital system.

What we know now is that chronic pain can’t be cured with a script for medication, especially opioids—powerful drugs that are best used for short-term pain relief. These drugs may still be used in the context of chronic pain in certain circumstances, but experts no longer look at them as a panacea, and we know they can cause a lot of harm. Over the past 20 years, the rate of fatal drug overdoses among adults over 65 quadrupled; in 2021, more than half of those deaths involved an opioid, according to JAMA Psychiatry.

These drugs aren’t just addictive; they actually ratchet up your nervous system responses, so pain threshold decreases while pain sensitivity increases. As opioids block traditional pain pathways, your brain and spinal cord work together to form new connections by which to transmit pain signals, making you even more sensitive. As a result, things that wouldn’t hurt you in the past can now cause pain.

If left to simmer, chronic pain can easily spiral, causing depression and anxiety, sleep deprivation, social isolation, and even economic and financial burden.

Pain management specialists now see a multipronged approach as the best way to deal with chronic pain. “There is not one single thing that can be done to make your pain better. We get the best results when we use all the tools in our toolbox,” Ashburn says. Painkillers, anti-inflammatories, implantable devices, nerve blocks, spinal cord stimulation and surgery may all play a role as important parts of your treatment plan. Several of the doctors we spoke with emphasized the importance of getting multiple medical opinions, especially before an invasive treatment, such as surgery.

Here are the primary nonsurgical approaches to pain management and how to access each.

1 Treat Depression and Anxiety

Chronic anxiety and/or depression symptoms are five times more common in people who have chronic pain than in those without, according to research in the journal Pain in 2024. Of course, it makes sense that you feel down when your back hurts every day, but treating those emotions is critical to relieving the physical sensations.

“If we fail to diagnose and treat depression in someone with chronic pain, we miss a wonderful opportunity to help that person,” Ashburn says. That may be done through therapy—some mental health professionals specialize in working with people with chronic pain—as well as medication. Interestingly enough, certain antidepressants are also effective for pain. “In that regard, you get a twofer,” Ashburn says.

2 Seek Out a Sleep Specialist

Pain makes sleep hard to come by, but lack of sleep makes pain worse. That’s why experts consider good sleep a foundational part of treatment. This includes diagnosing and addressing obstructive sleep apnea—a condition marked by brief pauses in breathing during sleep that becomes more likely with age. People with this disorder are twice as likely to live with pain problems than healthy folks, but treatment with a CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) machine was found to decrease pain symptoms, according to data in Scientific Reports.

Outside sleep apnea, taking a general lack of sleep seriously can play a big role in alleviating chronic pain. “If someone isn’t sleeping and I can figure out how to help them sleep, they will be in a much better position to be able to recover,” Ashburn says. Sleep hygiene includes maintaining a consistent sleep and wake time and setting up a cool, comfortable and quiet bedroom. Shut off all electronic devices at least 30 minutes before bedtime, suggests the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Avoid caffeine in the afternoon and evening, and don’t drink alcohol within four hours of your bedtime.

3 ‘Unlearn’ Your Pain

Pain reprocessing therapy, dubbed PRT for short, is a relatively new type of cognitive behavioral therapy specifically geared toward rewiring your brain’s experience with pain. “PRT involves being aware of pain in your body and reminding yourself that your brain may be sending out a false alarm,” Wager explains. This alarm signal involves your brain amplifying sensations from your body to guard against future harm. Wager likens this type of therapy to what you might do if you have a spider phobia. “The best way to treat that is with gradual, prolonged exposure to spiders with cognitive support,” he says.

It’s similar when confronting your pain. “It’s generally not helpful to push through or ignore pain altogether. This therapy acknowledges that the pain is real, but it helps you develop a new understanding of it, so you can say, ‘Actually, this pain is safe pain, and I can explore and test it,’ ” Wager says. Alongside a therapist, you’ll be guided to move in ways that you’re afraid of while reevaluating sensations and emotions that arise. The end goal is to challenge your beliefs about your pain and recognize that moving in certain ways is not physically harmful.

Gradually, this may turn down the dial on your pain and allow you to move with less fear. Research that Wager coauthored in JAMA Psychiatry found that 66 percent of people with mild or moderate chronic back pain said they were mostly or completely pain-free after twice-weekly PRT sessions for one month. You can find a therapist trained in PRT at PainReprocessingTherapy.com. In addition, many major medical centers have pain psychologists on staff; ask if your center uses or is familiar with PRT and can make recommendations.

4 Commit to Physical Therapy

Physical therapy—exercise, movement, heat/cold treatments—addresses pain, strengthens muscles, ligaments and joints, and helps you move in better ways. “I’m a huge believer in physical therapy,” says Timothy Furnish, M.D., a pain management specialist at the University of California San Diego. PT is a long-term commitment: “One of the things about physical therapy is that you have to do it for a while and commit to doing the exercise regimens at home,” but people often give up on PT too quickly, he says.

To make this work, you’ll need to have frank conversations with your doctor and physical therapist about what’s possible for you in terms of transportation, schedule and cost, Ashburn says. “You might not be able to go to physical therapy multiple times per week, but arranging a home exercise PT program once a week might be more doable—and that’s way better than nothing,” he says. And if you’re not meshing with your physical therapist (this can happen), look to make a change until you find one that fits your style.

A TENS unit may interrupt nerve impulses.

5 Scramble Your Pain

Easy to pick up at your local drugstore, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, or TENS, devices are budget-friendly, typically battery-operated, over-the-counter tools that use electrodes to send gentle electrical currents across the skin. TENS can interrupt nerve impulses that relay “danger” signals, which your brain can interpret as pain, from getting to the brain, explains Mark I. Johnson, professor of pain and analgesia at Leeds Beckett University in Leeds, England. The buzzy skin tingle generated by TENS distracts your brain away from twinges and tenderness. In a systematic review and meta-analysis in BMJ Open in 2022, Johnson and others analyzed data on more than 2,400 TENS participants; their results indicate that TENS showed an effect on pain reduction during or immediately after treatment.

The catch with TENS? Pain will likely come back shortly after you take the device off. “Think of TENS as something that soothes pain in the moment so you can do other things,” Johnson says. You might hook up to it before exercising or seeing friends. It can also be helpful at bedtime, providing the TENS device has an automatic timer so it switches itself off when you fall asleep.

A more effective and longer-lasting treatment is Scrambler therapy, which is administered in a doctor’s office and typically used to treat chronic or neuropathic pain.

“Scrambler therapy appears to actually reset the brain to inhibit pain for hours, days, weeks, even months after a few sessions,” says Thomas Smith, M.D., Johns Hopkins Medicine oncologist and palliative care physician. Smith estimates that in his experience, 60 percent of people get significant help with their pain for up to several months after 10 or fewer treatments; another 20 percent may get some relief.

6 Consult an Exercise Specialist

“One thing pain tells you to do is to stay in place, rest and not move,” Warraich says. Who wants to walk with a knee twinge or try to lift weights with a bum back? But being sedentary encourages muscles to weaken and muscle mass to decrease, accelerating the risk of age-related muscle loss and frailty. As you grow weaker, there are fewer activities that you can participate in that bring you joy, like walking in a park with friends. And that can take you down the road of depression. “Exercise is one of the things I recommend to the vast majority of patients with chronic pain. Exercise improves your functionality, which improves your pain, and your quality of life gets better,” Warraich says.

You may not be playing full-court basketball or pickleball, but other options include tai chi, yoga and stretching, Smith says. If you’re not sure what you can do safely, a visit with an exercise specialist or physical therapist can come in handy.

7 Master Mindfulness

The emotional anguish caused by pain presents a big hurdle in recovery, says Eric Garland, distinguished professor in the College of Social Work at the University of Utah. It’s natural to experience invasive thoughts such as:

▶︎ This isn’t fair.

▶︎ What if this pain never goes away?

▶︎ What if my pain means that something bad is happening in my body?

“These emotional reactions turn the volume of pain up and make it more intense,” Garland says. “Mindfulness is a way of observing this process of reacting negatively to pain and removing the negative emotions we place onto pain. When we learn how to use mindfulness to see our pain as pure sensation rather than emotional anguish, it can be easier to cope with and manage the sensation,” explains Garland, who developed a mindfulness program supported by the National Institutes of Health. The Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement (MORE) program serves as a treatment for chronic pain and opioid misuse.

“When we learn how to use mindfulness to see our pain as pure sensation rather than than emotional anguish, it can be easier to cope with and manage the sensation.”

The relief isn’t forever. Garland compares it to taking an ibuprofen. “When it wears off after a few hours, you take another dose. The same principle holds for mindfulness. You have to practice it again to refresh the pain relief.”

A similar technique is hypnosis. “We’ve shown that 15 minutes of hypnosis has pain-relieving effects comparable to mindfulness,” Garland says.

There are various types of hypnosis, but in Garland’s research, patients were asked to imagine creating pleasant sensations in the body, then superimposing those sensations onto the parts of their body that hurt. In a hypnotic state, you’d visualize spreading comfortable warmth or coolness, for example, to the problem areas.

One thing worth remembering is that chronic pain is not necessarily an indicator of tissue damage or poor health. “As a human, you want pain—pain is a protector, it’s good for you in certain situations,” Johnson says. “But sometimes the brain becomes overprotective and amplifies and prolongs pain when tissue damage has healed.”

Ultimately, the goal is to live well despite your pain status. “It’s not resigning to the fact that you’re in pain but focusing on prioritizing other aspects of your life and what matters most,” Warraich says. “The harder you try to control pain, the more powerful it becomes.” For many, letting go of the idea of being pain-free at all costs and focusing on what you can do to take back your life is what truly leads to healing.

Jessica Migala writes regularly on health for Women’s Health, Real Simple and other publications.

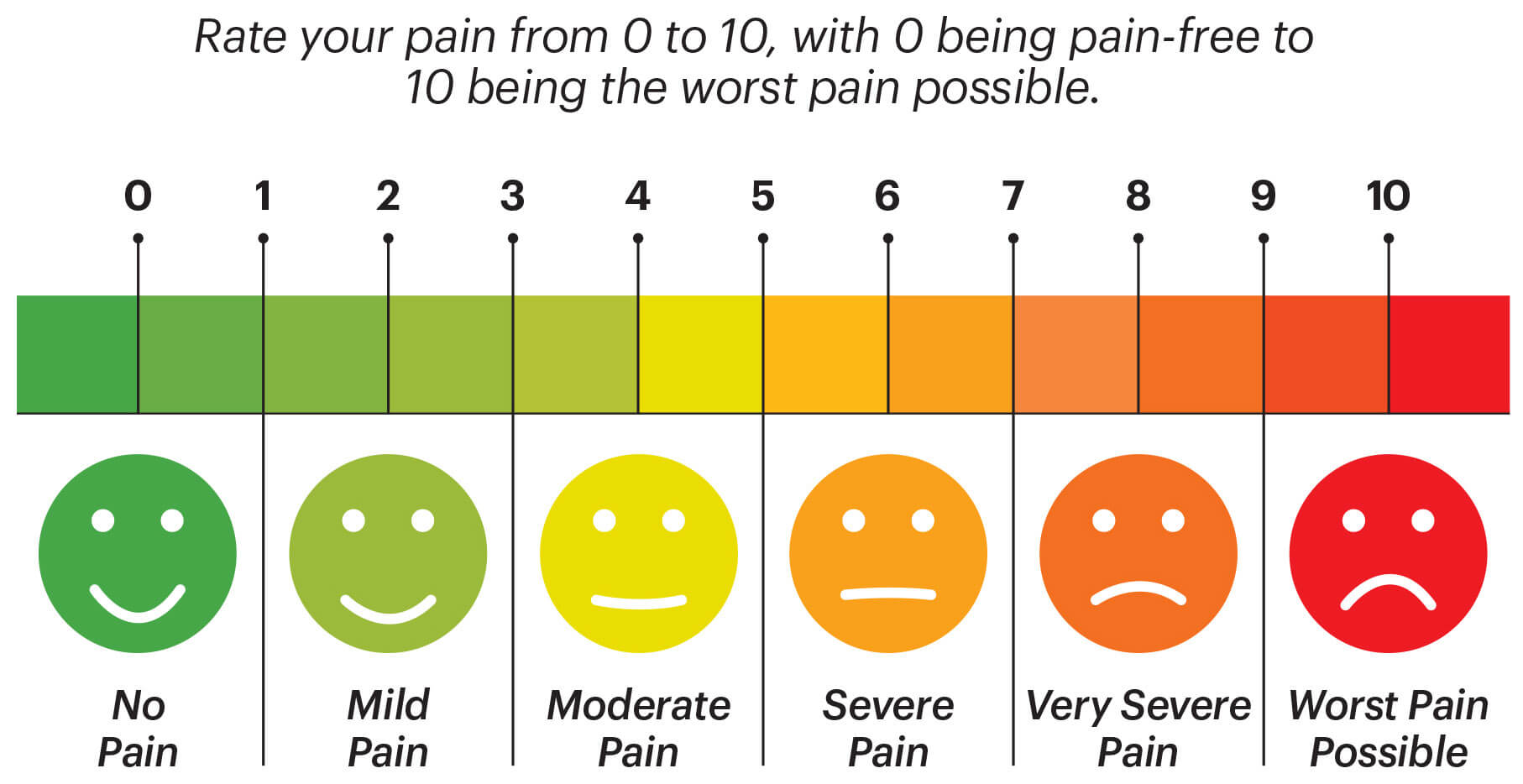

IS THE PAIN SCALE BS?

Have you been asked to use the pain scale? It’s ubiquitous in doctors’ offices and hospitals, but what does it actually tell you? “Pain is a completely subjective and personal experience,” says Timothy Furnish, M.D., a pain management specialist at the University of California San Diego. “Every person will experience pain and deal with pain a little differently.” Along with actual tissue damage, biological, psychological and social factors combine to create your pain experience, including: sex, race and ethnicity, age, genetics, disease, nervous system sensitivity, inflammation, brain function, mood, catastrophizing, stress, ability to cope, culture, social environment and support, and economic factors.

Think of the scale as a baseline before treatment, and revisit it during and afterward to get some sense of how your pain is affected.

THE UNIQUE CHALLENGE OF CANCER PAIN

Pain is one of the most common symptoms in cancer. Nearly half of patients with cancer experience pain, according to a meta-analysis of 444 studies. (Nearly 1 out of 3 characterize their pain as moderate to severe.) Older adults are less likely to bring up discomfort or ask for relief for a variety of reasons, including not wanting to bother their family or health care provider or the fear of side effects from medication. “Some patients are afraid to talk about their pain. But it’s important to acknowledge that pain exists,” says Salahadin Abdi, M.D., a cancer pain specialist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Pain can be a symptom of cancer and arise at any stage of the disease. It can be caused by radiation treatment or chemotherapy, or linger after surgery. Whatever the cause or your stage of disease, you deserve relief. But your doctor can’t help you find it if they don’t know about your discomfort. Talk to your oncologist and health care team about a pain management approach as soon as possible. “Cancer pain can be really significant, which is why we as pain physicians want to see cancer patients early in the stage of their disease. If we don’t see them early enough, just like any other disease, like hypertension, it could be difficult to undo the problem,” Abdi says.

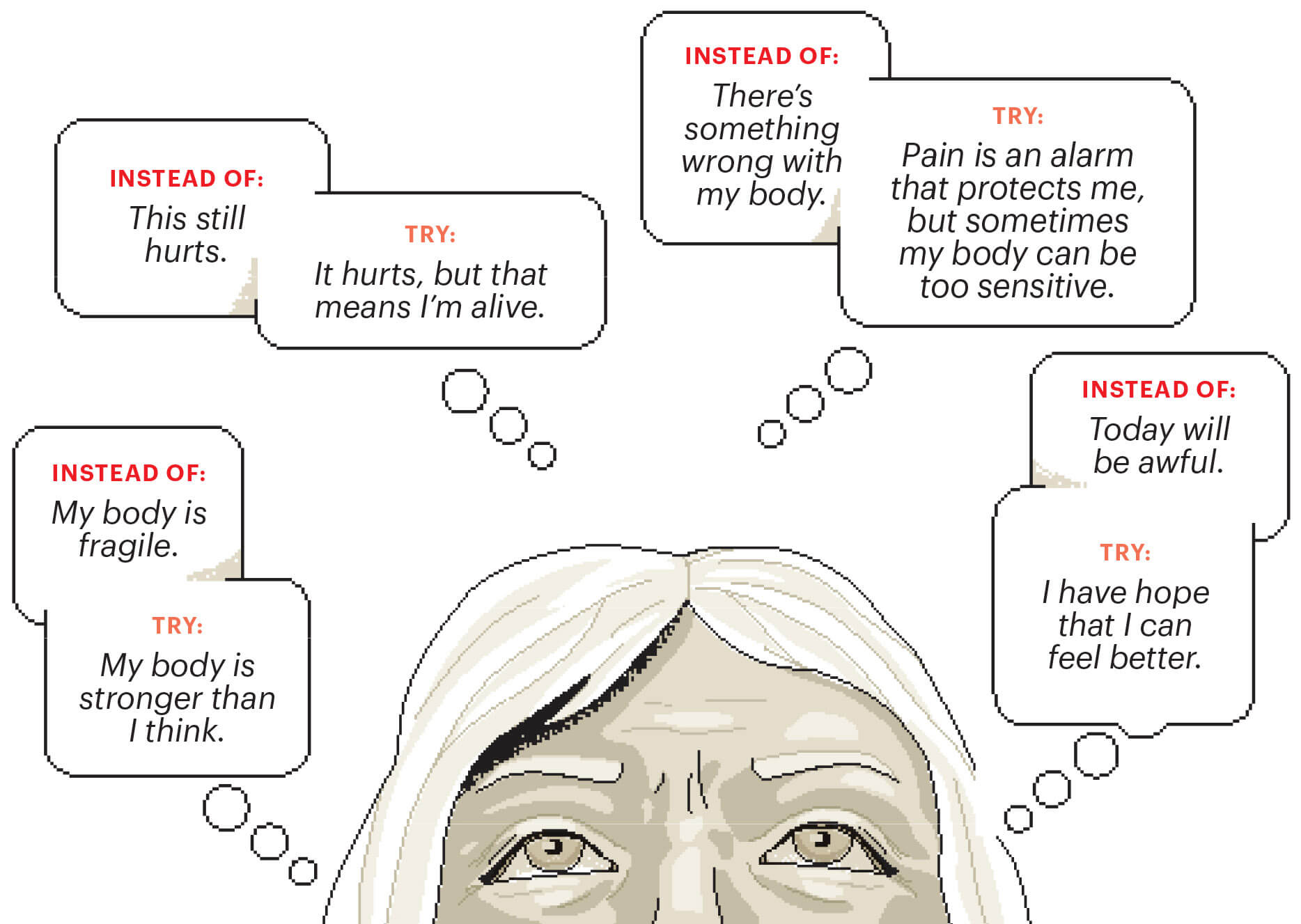

CHANGE YOUR INNER MONOLOGUE

How you talk about your pain matters in terms of its intensity and your journey toward healing. Here are some ways doctors suggest to change up your inner monologue.