Cover Story: Special Report

Some people 90+ have the memory, thinking skills and zest for life of people decades younger. Researchers are starting to figure out why—and how more of us can age the same way

You can find Vernon Smith at work at his computer by 7:30 each morning, cranking out 10 solid hours of writing and researching every day.

His career is incredibly demanding—he is on the faculty of both the business and law schools at Chapman University. But the hard work pays off: Smith’s research is consistently ranked as the most-cited work produced at the school—a testament to his ongoing influence and success. He manages both jobs and his research work while cowriting books and traveling around the country delivering lectures.

It’s a remarkable level of productivity, made all the more remarkable by one simple fact: Vernon Smith is 96 years old.

Smith, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences at age 75, says he feels the same passion as he did when he embarked on his career more than seven decades ago.

“Except for the fact that I don’t actually do experiments myself anymore—my coauthors do those—I think I’m as good or better than ever, partly because I have knowledge across several areas that my younger [colleagues] are in the process of acquiring themselves,” Smith says. “So we’re a good match.”

What accounts for Smith’s extraordinary capabilities as he nears 100? Why is he thriving while so many of his contemporaries are grappling with physical and mental decline?

And what can we do to ensure that our 90s and beyond are just as fulfilling?

THE PUZZLE OF THE SUPER AGER

Researchers are attempting to answer these questions by studying people like Smith, who is one of 1,600 participants in the University of California, Irvine’s 90+ Study, a research project examining successful aging and dementia in people 90 years and older. Scientists and gerontologists are recruiting individuals who demonstrate remarkable memory and evaluating their physical health and lifestyles. The researchers observe the brains of their subjects using MRIs and scans, test for biological markers and conduct postmortem studies on those who have donated their brains after death (many study participants do)—all in an effort to understand this small but extraordinary group of men and women who, like Smith, are categorized as “super agers.”

A “super ager” is someone over 80 with an exceptional memory—one at least as good as a person 20 to 30 years younger.

Many people think they have good memories, but super agers are actually quite rare, says cognitive neuroscientist Emily Rogalski, who leads the SuperAging Research Initiative across five cities around the United States and Canada. Less than 10 percent of the individuals who sign up to participate in her studies have the memory and mental capacity to meet the scientific criteria for being super agers, she says.

“We don’t often celebrate what’s going right in aging, only what’s going wrong,” says Rogalski, who was one of the first researchers to use the term “super ager.” “We’re still at the beginning of this journey, but super agers provide a great opportunity for teaching us quite a bit.”

It’s a critical mystery to crack. As 73 million boomers hit their 80s, and medical advances expand the opportunity to live longer and longer lives, conquering the onset of dementia has never been more important. “Brain aging needs to match longevity,” says Matt Huentelman, who leads genetics studies for the SuperAging Research Initiative. “Today your body may make it to 100, but your brain poops out at 80.”

SUPER BRAINS AND THE PEOPLE WHO OWN THEM

Most of us have brains that will age and change in similar and predictable ways. Memory peaks between the ages of 30 and 40. Overall brain volume begins to atrophy in our 50s, particularly in the areas of the brain linked to complex thought processes and learning. Changing hormones, deteriorating blood vessels and difficulty managing blood glucose—the brain’s primary fuel—lead us toward the cognitive decline associated with aging. These factors explain why we may have trouble retrieving a word or remembering a name to match a face as we get older, and why multitasking and processing new information become more challenging.

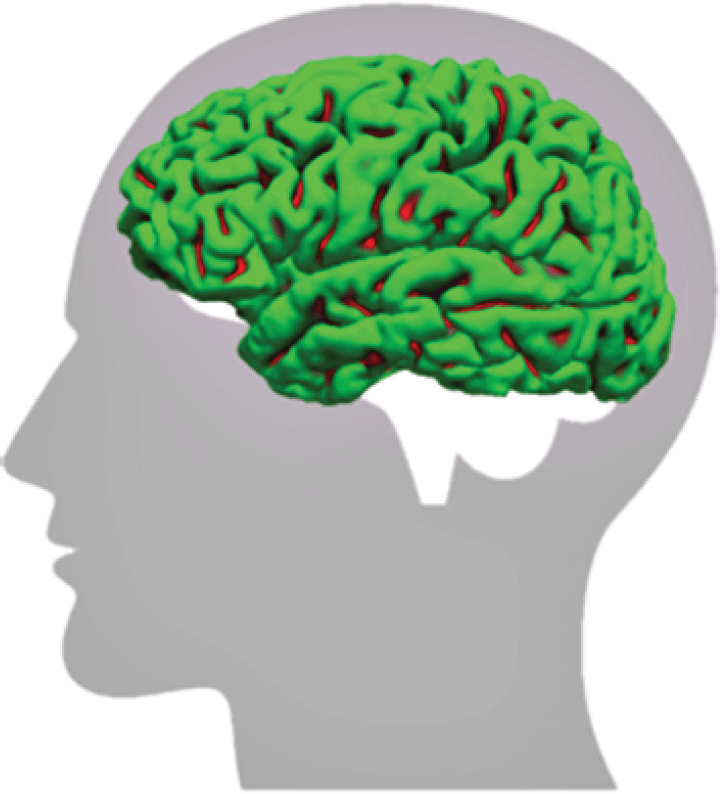

64-year-old, cognitively normal

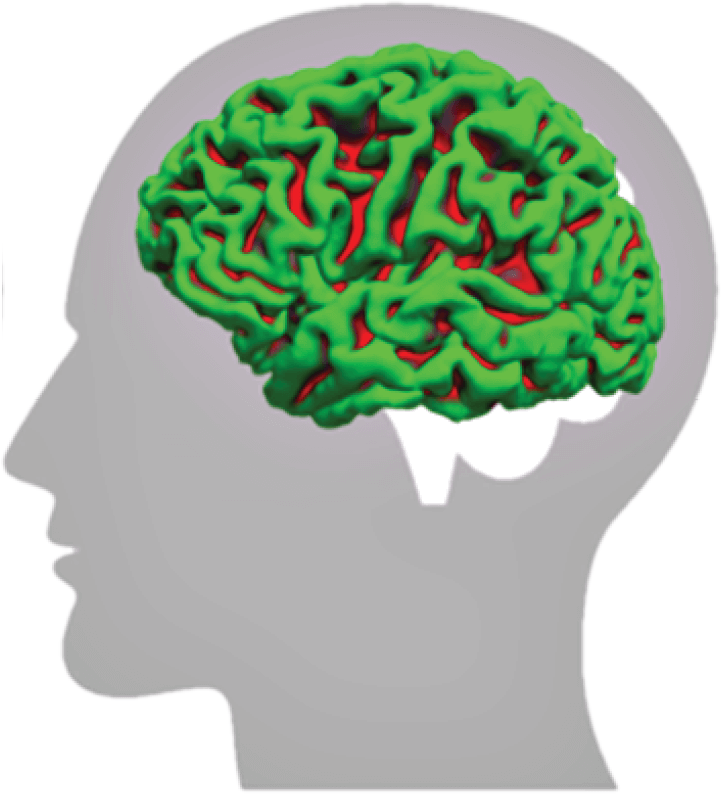

84-year-old,cognitively normal

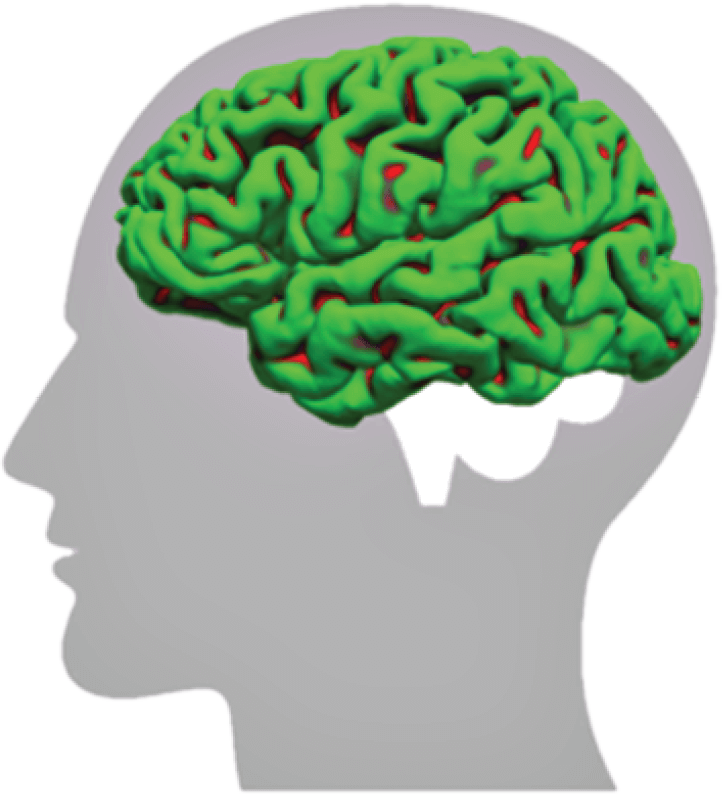

85-year-old, super ager

But the brains of super agers don’t behave this way. Among the differences:

▶︎ Super ager brains are shrink-resistant.

That is, they shrink at a slower rate than the brains of similarly aged people and maintain volume in the areas associated with memory and focus. The SuperAging Research Initiative team identified a potential “brain signature” for super agers: They found that the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which impacts thinking, memory and decision-making, is thicker in super agers—sometimes thicker even than in most people in their 50s and 60s. In some super agers, the brain regions linked to memory storage and retrieval were so well preserved that they were indistinguishable from young adults, says Brad Dickerson, a behavioral neurologist and director of the Frontotemporal Disorders Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital and professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School.

▶︎ Super ager brains have memory cells that are supersized.

The neurons around the brain responsible for memory are significantly larger in super agers than in their peers, and even compared with individuals 20 to 30 years younger. These neurons tend to be free of “tau tangles,” the webs of tangled proteins that collect inside neurons in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease and other kinds of dementia.

▶︎ Super ager brains have more “social intelligence cells.”

They contain a higher volume and density of spindle-shaped “von Economo neurons,” cells that have been linked to social intelligence and awareness. These cells help facilitate rapid communication across the brain, providing an enhanced ability to navigate the outside world.

These factors seem to combine in a way that keeps the brains of super agers from declining with age—and we’re not just talking about what happens in their 80s and 90s. In 2016, Dickerson’s team gave younger super agers, ages 60 through 80, a list of 16 unrelated words, which they were asked to repeat back 20 minutes later. An average 25-year-old can usually recall 14 words, and the average 75-year-old will remember nine words. But super agers in the study remembered just as many words as the 25-year-olds. Another study found similar results: Super agers who took a tough memory task test while in an MRI scanner were able to learn and recall new information as well as study participants who were 25 years old.

DECODING THE MAGIC FORMULA

Why are super agers resistant to age-related decline, to the point where their brains at age 90 function better than the average 60-year-old's? Three factors may be at play:

▶︎ Cognitive reserve

It’s not that their brains don’t age; it’s that super agers seem to be able to overcome the wear and tear that cognitively average people succumb to—age-related issues such as inflammation or clogged blood vessels. Postmortem studies of the brains of super agers reveal that some have the clinical pathology of Alzheimer’s disease, but never experience any of the symptoms.

That is, some brains may have an added power that allows them to keep functioning well despite the presence of disease or the markers of cognitive decline. Since longer life and healthier cognition seem to run in families, it may be that this ability is genetic, but scientists don’t yet know. That said, genes are like programs on a computer: Having those super ager genes is the first step, but genes can be “turned on” or “turned off” by environmental factors and lifestyle choices.

▶︎ Life achievement

People with higher education levels or greater career attainment tend to have greater cognitive reserve, says Yaakov Stern, professor of neuropsychology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, who studies this aspect of brain health. But we don’t know whether educational and career success increase the chance of becoming a super ager, or whether the natural cognitive advantages of these folks simply make them more likely to succeed. Interestingly, a recent study conducted at Massachusetts General Hospital at Harvard Medical School found that higher educational achievement and more years of schooling could act as a protective factor and slow down cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s even in individuals with strong genetic risks for dementia.

On the other hand, it may be that the natural mental abilities of super agers make them more likely to set off on advanced studies or successful career trajectories, or to grab those late-career brass rings. It’s one of the factors researchers plan to study when looking at the impact of socioeconomics on super aging.

▶︎ Lifestyle

This may be the big one. Several clues are starting to emerge that draw parallels between the lifestyles of super agers. Healthy-aging researchers have identified four common habits:

• A physically and intellectually active lifestyle

• The willingness or ability to constantly challenge oneself

• An active social life and a wide social network

• Moderation in all indulgences, but allowing for the occasional glass of wine, for example

While myriad studies underway are probing the biological, genetic and scientific underpinnings of super agers, lifestyle and environment remain significant and consistent factors that most likely contribute to superior aging.

In addition to maintaining the above four habits, super agers make other lifestyle choices that seem to have an impact. Eating Mediterranean style (lots of produce, not too much red meat), daily exercise and actively managing stress levels and mental health issues are all shown to have a positive effect on cognition. Conversely, studies have documented the negative impacts of loneliness and social isolation, and even poor hearing and vision, on cognitive health. Passively sitting back watching television? Not on the list of things to do if you want to be a super ager.

A strong social network doesn’t mean you’ll never get Alzheimer’s disease, Rogalski says. But maintaining strong social networks could be on the list of healthy choices, like eating a certain diet and not smoking. [See “7 Secrets of the Super Agers.”]

Researchers concede there is much they still don’t know about what makes a super ager. For example, the medical problems and health-related concerns of super agers are comparable to the health profiles of normal agers. According to Rogalski, studies have shown that the use and types of medications super agers take are pretty much the same as those used by people with average memory for their age. And there are super agers who have a range of diseases, from lymphoma to osteoarthritis; many use wheelchairs, despite their excellent cognitive health.

“Not all cognitive super agers are also physically exceptional,” says researcher Angela Roberts of the Canadian Centre for Activity and Aging.

Roberts and her team have been collecting data on lifestyle factors by attaching wearable sensors to study super agers. Though findings are preliminary, they show that super agers in the study do 60 minutes a day of moderate to vigorous physical activity, some as much as 90 minutes, which is well above the 150 minutes a week that’s generally recommended for older adults. Sensors also show that super agers tend to get more high-quality, uninterrupted regular sleep than non-super agers.

Researchers are starting to look at other factors, including the vascular and cardiac health of super agers versus non-super agers, given that vascular health is critical to how the brain ages. Researchers suspect that the cardiovascular systems of super agers may be more “dynamic” than those of typical people their age. They also hypothesize that super agers may have a protective pathway of sorts that may affect the development of dementia and other aspects of health.

“The idea is as we age, our entire system becomes less dynamically responsive,” Roberts says. “We are exploring the genetic and lifestyle factors that help people age exceptionally from a cognitive perspective.”

HITTING THE BIG 100

Some scientists say the best chance of understanding super agers may come from studying the oldest of this cohort. That’s the premise behind the SuperAgers Family Study, which was started last year, led by the American Federation for Aging Research and Albert Einstein College of Medicine in collaboration with Boston University School of Medicine. It has an ambitious goal: to enroll 10,000 individuals who are 95 and older—and their children. The mission is to identify inherited and behavioral and environmental factors that protect against human aging and related diseases as individuals near the century mark.

About 1 in 4,000 Americans are 100 or older, according to Census Bureau statistics. Some of these individuals have the cognitive functioning of people who are 30 years younger, says Thomas T. Perls, a geriatrician at Boston University and founder and director of the New England Centenarian Study.

“They’re the crème de la crème of our population,” Perls says. “What’s special in these people is that they have some protective genes that slow aging and decrease the risk for age-related diseases like Alzheimer’s.”

“A GOOD DIET MATTERS. GET AS MUCH EDUCATION AS YOU CAN. IT CONFERS LIFELONG PREVENTION.”

Indeed, findings from a recent study of centenarians in the Netherlands show that if someone reaches 100 with their cognitive abilities intact, they are likely to remain cognitively superior, except for a slight memory loss. This was true even if an examination of their brains after death showed the tau and amyloid plaque associated with Alzheimer’s.

Turning 100 was a big deal for Boca Raton, Florida, super ager Phil Horowitz and his family, including his two children, six grandchildren, five great-grandchildren, and a far-flung network of nieces and nephews. (Disclosure: Horowitz, now 102, is this writer’s uncle.)

Longevity runs in Horowitz’s family. His mother died at 104; his four siblings lived well into their 90s—the youngest, a set of twins, are both still alive at 100. But none have the cognitive health or vitality that Horowitz does. The centenarian retired to Florida years ago with his wife, Estelle, who died two years ago. Now he lives alone, but his children fly down often, and his grandson who lives nearby visits all the time. Horowitz plays poker and teaches Yiddish once a week to a group of residents in his assisted living facility.

Last year, Horowitz completed his memoir, written in longhand cursive (he admits he started on a computer, then mistakenly erased everything and decided to go the old-fashioned route). “I have a good memory for dates,” he says, “so I decided to write my memoir chronologically starting when I was 7 years old.”

THE IMPORTANCE OF PASSION

At 91, Frances Ito packs her schedule with gardening, online tai chi, weekly jam sessions with other musicians, art projects, Bible class via Zoom, volunteering at her church, exercise and moviemaking—which she took up in her late 70s. During the pandemic, Ito discovered the joy of reading and finished 20 books (“biographies, nonfiction and histories”).

Despite cardiac issues and a few other health problems, Ito’s vitality and engagement earned her a spot in the University of Southern California's super agers program. From learning the ukulele—an homage to her home state of Hawaii—to growing fruits and vegetables on her drought-resistant front lawn, Ito refuses to surrender to aging. She’s having too much fun. Her latest film, The Purpose Driven Life, about her experiences as a super ager, was released in May.

“I think the secret is attitude,” Ito says of her cognitive health.

Perhaps. What we do know is that becoming a super ager is the result of a complex combination of factors that account for superior memory and cognitive health.

“The hard part is proving it,” says Claudia Kawas, an investigator for the 90+ Study. “Everyone wants it to be one thing, like blueberries or crossword puzzles. I don’t think it’s that simple. A good diet matters. Get as much education as you can. It doesn’t mean Nobel laureates don’t get Alzheimer’s, but at a lower rate. It confers lifelong prevention through some mechanism that we don’t understand yet.”

Currently, there is no way to predict who will be a super ager with any degree of certainty when someone is younger—40, 50 or even 60. “Those are open questions at this point—but future directions for sure,” Huentelman says. More likely is that within the next decade, researchers will learn which genes may play a role in making someone a super ager to better understand the optimal pathways for aging well, and ways we can slow or prevent age-related diseases such as dementia. “We will know how they stay on that course and what components might be identifiable based on lifestyle and other factors,” Roberts says.

Look at Nobel winner Vernon Smith, who has spent his life working on economic theorems and academics and has three degrees, including a doctorate from Harvard in economics. His passion remains his profession. Despite his enormous workload, he wouldn’t consider retiring.

“Why would I do that?” Smith says. “I’d just do the same thing I’m doing now and wouldn’t get paid for it. I have an ancestor who lived to be 105. I want to live at least to 106.”

Jeanne Dorin McDowell writes about health, science and social issues for such publications as National Geographic, Smithsonian and Scientific American. Previously, she was a correspondent for Time magazine.

SUPER AGERS SPEAK!

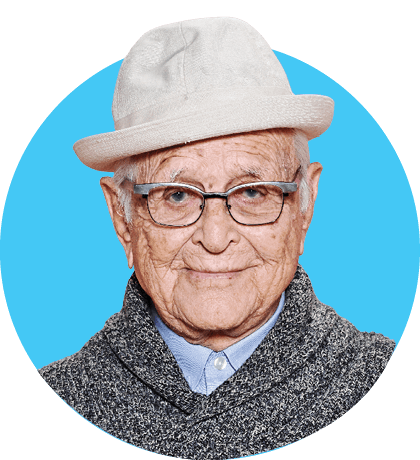

NORMAN LEAR, 101 Award-winning television producer and screenwriter (All in the Family, One Day at a Time)

SECRET WEAPON: GRATITUDE

“I can only attribute [being a super ager] to what is known in common parlance as the luck of the draw. … I would add one factor only, and that is gratitude. The hour-by-hour feeling of appreciation for the gifts with which we are born or have had the ability to accumulate.”

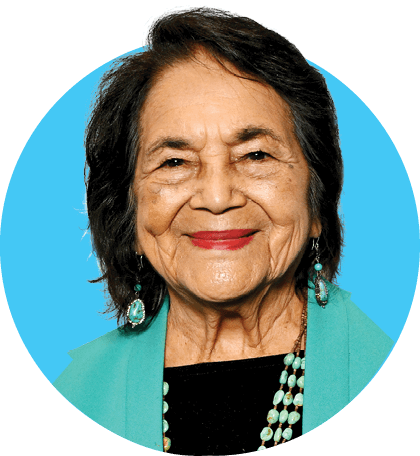

DOLORES HUERTA, 93 Labor leader and civil rights activist, president of the Dolores Huerta Foundation

SECRET WEAPON: STAYING INVOLVED

“I get energy from people. Keeping involved keeps my brain active. There’s so much work to be done, so many organizations that need volunteers. If people keep busy, their brains can keep busy. ... My mother died at 51, and my dad died in his 70s. I’m very blessed that I have been able to live as long as I have.”

RUTH WESTHEIMER, 95 Sex therapist, talk show host, author of two new books including the revised The Art of Arousal

SECRET WEAPON: A LOVE OF LIFE ... AND TALKING

“When I was 10 years old, my family made the sacrifice of sending me to Switzerland. That’s how I survived [the Holocaust]. For six years I was in an orphanage in Switzerland, hoping the parents could get out. They did not, but my love for life and my attitude toward life is because of my early years. Also, I exercise. And I exercise my mouth. I talk day and night. It exercises my brain.”

STANLEY PLOTKIN, M.D., 91 World-renowned vaccinologist who developed the rubella vaccine

SECRET WEAPON: PROBLEM-SOLVING

“I belong to an ‘Old Friends’ group of eight or 10 people in their 90s, so we meet by Zoom and talk about our experiences. I’ve always enjoyed music, art, travel. I’m interested in history, philosophy, science, many things other than my work. Stimulation is a large part of it. If you continue to think about problems and try to solve them, it keeps you younger.”

THADDEUS MOSLEY, 97 Sculptor with a 2022 exhibition at the Eugène Delacroix Museum in Paris

SECRET WEAPONS: PHYSICAL EXERCISE AND READING

“I can still lift 125 pounds. I’ve always been very strong. And I read, mostly anything that is factual—cosmology, history, society. Today I’m reading the Sunday Times. I’m in the studio every day unless someone takes me to lunch or dinner. To me, you must have something to live for.”

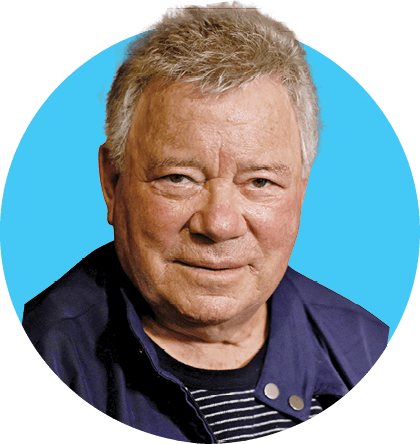

WILLIAM SHATNER, 92 Actor, author and (at age 90) astronaut

SECRET WEAPON: PASSION FOR THE FUTURE

“My concern is about my children and grandchildren and the life they will lead, given what we know is happening. ... Traveling into space was a gigantic emotional experience. The truth of it is, I felt great grief as I realized how so many things are going extinct while you and I are talking. I saw the beauty of the world and the harshness of space and realized what we are doing to our Earth is so ugly.”

BETYE SAAR, 96 Artist with 2023 solo exhibitions in Boston and Lucerne, Switzerland

SECRET WEAPONS: GARDENING AND ARTWORK

“I love gardening. My mother was an avid gardener, and I think I’ve passed that on to my daughters as well. I look forward to eating good food, resting and looking up at the moon and the stars. I don’t think about my age when I’m making art. Ideas for art are always young.”

AARP’s Take On Aging Well

THIS STORY IS ADAPTED from a special digital-only edition of AARP The Magazine, marking AARP’s 65th birthday. Other articles in the edition include:

▶︎ The No. 1 exercise for aging Doctors agree this move is most essential for vitality.

▶︎ Make your money last Four proven approaches to stretching your retirement cash.

▶︎ Age defiers! Martha Stewart talks aging, plus tributes to baseball legend Dusty Baker and artist David Hockney.

▶︎ A new definition of healthy What many older people consider “healthy” is at odds with what doctors think. Why that matters.

▶︎ Age in place—by moving?

The rise in age-smart housing options right in your neighborhood.

Read these and more beginning Nov. 10 at aarp.org/bonus-issue or on the AARP Publications app: Easy download instructions are at aarp.org/pubsapp.