FEATURE STORY

The Oldest Hatred

Antisemitism has persisted century after century, with the murder of 6 million Jews in the Holocaust its most horrific incarnation. Some Americans may have thought this prejudice was fading away, but it has gained momentum once again. What to make of today’s attacks on Jews, and what can be done about it

Interviews by Jane Eisner

ILLUSTRATION BY DOUG CHAYKA

THE SIGNS ARE everywhere: Swastikas projected onto a building in West Palm Beach, Florida. Antisemitic flyers thrown onto lawns in Atlanta suburbs. A Kanye West post on social media announcing, “I’m going death con 3 On JEWISH PEOPLE.” Eleven worshippers killed in an attack on a synagogue in Pittsburgh. To understand what’s behind this current wave of antisemitic beliefs and incidents, we turned to Ambassador Deborah Lipstadt, the State Department’s special envoy to monitor and combat antisemitism. A longtime professor of Jewish studies at Emory University, Lipstadt has written several award-winning books about the Holocaust and other aspects of modern Jewish history.

Let’s start with the basics. In the U.S. today, there’s no simple picture of Jewish life. You have Jews who are extremely observant—who follow strict dietary laws, who dress a certain way, who don’t work or drive from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday. At the other end of the spectrum, you have people who maybe go to synagogue once a year and identify as Jewish. In this context, how do you define antisemitism? What does it look like today?

It’s a prejudice like other prejudices—a hatred of Jews. But it’s also a conspiracy theory that cuts across ideologies, nationalities, ethnicities. It’s someone who says, “Jews are all-powerful. They control the media. They control the banks, the government.” Or, “Jews are all privileged.”

It comes from Christians, it comes from Muslims, it comes from atheists. It even comes from other Jews. One sees it in a variety of forms—on the governmental level, in the media, on the streets. It looks like it’s increasingly normalized. That’s what’s frightening to me. That it’s OK.

ANTISEMITISM’S LOSS IN COURT

In 2000, Lipstadt won a high-profile libel case brought against her by a Holocaust denier—a legal battle recounted in her book History on Trial and depicted in the 2016 feature film Denial.

Is it really different from other prejudices, like racism or sexism?

Jews don’t fit the picture of your traditional victims of prejudice: “If you look so secure and so successful, what are you complaining about?” So, the Jewish kid on scholarship in my class at Emory—who’s also doing work on the side so she won’t graduate with $100,000 in debt—has to justify that she’s not privileged. Whereas with prejudice against other groups, this lack of privilege is taken at face value. We may present as educated and financially secure, even though we know very well there are many Jews who are not.

There’s another way in which antisemitism is different from other prejudices. With most racial and other prejudices, people simply look down upon the other. But antisemites punch down and punch up simultaneously. They look down on Jews and see them as lesser human beings—dirty.

And they look up and see them as more powerful, as conniving and as a threat to the antisemite’s well-being. And if Jews pose a danger to your well-being because they are conniving and crafty, then you have to protect yourself by any means necessary.

And yet, in contemporary America, there’s also an admiration of Jews. Intermarriage rates are high. How do you make sense of that?

Jews are much admired for their accomplishments, but sometimes that admiration can turn on a dime into hostility.

What sort of mistakes do we make in our thinking about antisemitism?

One mistake we make is to fail to take it seriously. And that has a number of consequences, one particular and one more universal.

The particular: If there is a group in your society—a racial group, ethnic group, religious group, whatever it might be—that is under attack, you as members of that society and certainly the government of that society have a responsibility to protect that group. A government’s main job is to protect its citizens. That alone would make it a legitimate enterprise for a government to fight antisemitism.

But there’s a bigger danger to allowing antisemitism to exist, and that’s because antisemitism, like other forms of prejudice, is a canary in the coal mine and a threat to democracy. Remember, it’s a conspiracy theory that Jews control the media, the banks, the election process, etc. If you believe that there is a group controlling these things, then essentially you’re saying that you don’t believe in democracy. So, this belief is a danger to a particular group in your society, and it’s also heralding the death knell of democracy.

Is the current state of antisemitism in the U.S. different from past iterations?

It isn’t different in that it uses the traditional stereotypes and the traditional accusations. What’s different today is the delivery system. When I first started working on Holocaust denial, if I wanted material that deniers were sending, I had to go to an archive that collected this material. Now you’ve got a delivery system online that spreads this material everywhere and very quickly.

Is there a connection between antisemitism and political beliefs?

Antisemitism comes from all places on the political spectrum. Right now the much stronger manifestation of physical danger comes from extremist right-wing, white supremacist, white nationalist groups. The guards in front of synagogues—and there’s no synagogue that doesn’t have some sort of guard in front of it these days—are guarding against either right-wing militias or Islamic terrorism. They’re not guarding against a progressive person coming down the street.

20% of Americans hold at least six different anti-Jewish beliefs, according to a survey by the Anti-Defamation League.

But on many college campuses, you hear of Jewish students having to defend their Jewish identity. They have to downplay it instead of being proud of who they are. In a study I read recently, for example, one student said she identified herself as a Jew in one course. And for the rest of the semester, any time she commented on anything, her Jewish identity would be shoved back at her. Whereas five or six years ago, students on campus had a whole different experience.

It’s a fool’s errand to get into a debate as to which type of antisemitism is worse. One may be more dangerous than the other, but that doesn’t mean that all kinds shouldn’t be dealt with seriously.

And that gets us to campus protests about Israel. How do we draw a line between legitimate criticism of Israel and antisemitism?

Criticism of Israeli policy is not antisemitism, just like criticism of American policy is not anti-Americanism. But when it begins to ascribe to Israel antisemitic characteristics—that the Jewish state is all-powerful, that it is rich, conniving, and all you have to do is take out the word “Israel” and put in “Jew”—then you’re on that slippery slope of prejudice.

If you question the right of Israel to exist because it’s a Jewish state but fail to question the right of Islamic states to exist because of their religious identity, you have to wonder why.

Some people say that Israel doesn’t have a right to exist because it chased out an Indigenous population. There’s a big debate about whether that’s correct, but let’s say for the moment that the Jews displaced the Indigenous population. What about the United States of America and the Native Americans? What about Canada and the First Nations? What about Australia and the Aboriginal people?

I’m not justifying any of these things. I’m asking, “Why in this one case do they say, ‘Israel doesn’t have a right to exist,’ and not these other countries?” When you hold it to a different standard, when you subject it to this singular focus and ignore others, then you have to ask, “Where is that coming from?”

Why should non-Jews care about antisemitism?

It’s a great question, and I would say the following. Antisemitism, which has a long, terrible history, has never led to good things for society at large. We’ve seen in the lifetime of people still walking the face of this earth what it can do. One out of every three Jews in the world were murdered by the Nazis.

Had the Germans won the war, they probably would have eliminated lots of other people—lots of Ukrainians, Slavs, Mongols. Only the destruction of the Jews could not wait. Antisemitism injects hatred into society. It injects contempt into society, and distrust. It breeds no good.

In some European countries, Holocaust denial is illegal. Should antisemitic speech be curtailed here in the United States?

Oh, no. That would be impossible, because of the First Amendment. But we can make it unacceptable. The use of the n-word is not illegal, but it’s increasingly unacceptable, and that’s a good thing. Even people who use it in their heads increasingly know that it’s unacceptable in respectable society.

So, what works to confront antisemitism, and what doesn’t work?

What I think is absolutely essential is people speaking up, people speaking out, whether it’s the host of a dinner party or the person who has 38 million followers on TikTok. We have to make the antisemite into the social pariah. It’s not to be rationalized. It’s incumbent on everyone to speak out, to make it clear that it’s unacceptable. There’s no standing silent.

When you hear or encounter any form of oppression, any form of discrimination, if you stay silent, then you’ve sided with the oppressor.

Jane Eisner, director of academic affairs at the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University, is a former editor in chief of the Forward.

LIVING WITH ANTISEMITISM

Jewish Americans Speak Out

“It’s extremely unnerving.”

Rabbi Benjamin Goldschmidt leads the Altneu, an Orthodox synagogue founded last year in Manhattan.

• SOME OF THE older members of our synagogue remember when they were more concerned about being mugged than being berated as a Jew. Now it’s the reverse.

If you’ve never experienced antisemitism before, it’s extremely unnerving. I experienced much worse as a child growing up in Moscow. For me, New York is an incredible place for Jews to live. And yet, for the first time since I came here, many American Jews look at America as a place where they won’t be able to stay for long. That’s the greatest shift over the past decade.

“More people need to be educated about Judaism.”

Rabbi Sandra Lawson is director of racial diversity, equity and inclusion at Reconstructing Judaism, the central organization of the Jewish Reconstructionist movement.

• FOR A LONG time, American Jews believed that staying in our own communities was the safest thing to do. I can see that. The challenge with that today is the internet. Once something is online, you have no control over where it goes.

I sit at the intersection of Blackness and Jewishness. It’s my daily lived experience. I see that people can be racist and antisemitic regardless of their political perspective.

More people need to be educated about Judaism. We should get over the fear that we had about sharing our Jewishness. It’s not helping the community. It’s helping antisemitism to exist.

“It’s not like Jews are the only people to be hurt by the human capacity to hate.”

Kenneth S. Stern is director of the Bard Center for the Study of Hate.

• WE TEND TO think of antisemitism in the narrow aspect of “What are people saying about Jews?” The larger frame to look at is when anyone in our society is outside the social contract—when there’s an “us” and a “them.” That raises the likelihood that antisemitism will increase.

Too many times the mantra in the Jewish community is that antisemitism is unique. I get it. But it’s not like Jews are the only people to be hurt by the human capacity to hate. If we don’t look at what we know about how human beings are divided into “us” and “them,” we lose a larger understanding of what antisemitism is.

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Timeless Wisdom About Prejudice

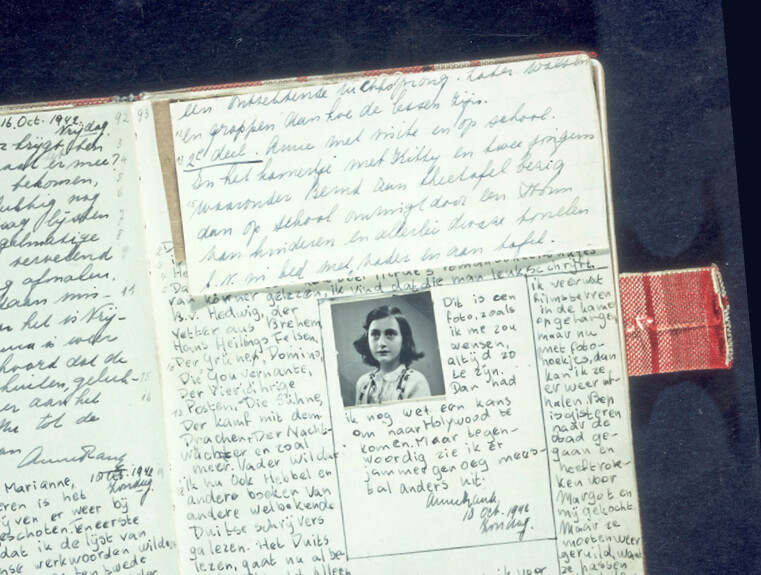

Anne Frank wrote about her life in hiding.

FOR TWO YEARS during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, a young Jewish girl, Anne Frank, hid with her family in the secret annex of an Amsterdam office until they were discovered and deported. Frank died in a German concentration camp in 1945 at age 15, but the diary she kept while in hiding, published after her death, became a world-famous testament to a life cut short by hate. The building where she hid is now a museum and center that teaches about bias and discrimination. These insights, adapted from the website of the Anne Frank House (annefrank.org), are instructive to us all.

ALL OF US PUT LABELS ON OTHERS … We categorize people from an early age. We learn differences between men and women, old and young. We notice different skin colors and religions. Without really thinking about it, we apply these categories to family, friends and strangers.

… TO HELP US NAVIGATE THE WORLD. Categorizing people keeps things simple. It’s easier to assess new situations by making connections between groups of people and the way they usually behave.

BUT THESE VIEWS CAN CALCIFY. This natural tendency becomes a problem when the connections you’ve made between categories and behavior turn unshakable—when you’re sure that all members of a specific group will behave a certain way.

HATE CAN HAVE WEAK FOOTING. Stories rather than facts often form the basis for prejudice. An unpleasant experience with one person from a certain group of people can also make us biased against the whole group. If you don’t base your ideas on facts or never adjust them, biases start to affect how you act.

PREJUDICE CAN BE CONTAGIOUS. If negative things about a specific group are constantly repeated, more and more people may end up believing them. This leads to discrimination—whole groups of people being treated unequally on the basis of group prejudice.

SO SPEAK UP … If someone around you does something based on prejudice, make yourself heard. Ask that person to tone it down, and say that you’re not OK with offensive prejudices, whether or not they affect you personally.

… USING YOUR COMMON SENSE. That, plus empathy and humor, will be your most important assets. If you end up in a debate, questions may be more effective than facts, figures and arguments. Questioning others can lead them to question themselves over the long run.