COVER STORY

Kevin Costner Goes His Own Way

At 69, the Yellowstone actor is about to enter his fifth decade of making movies. He’s still in love with the work, doesn’t follow trends and cares little for critical approval. “I don’t fall out of love,” he says. “A good idea is still a good idea.”

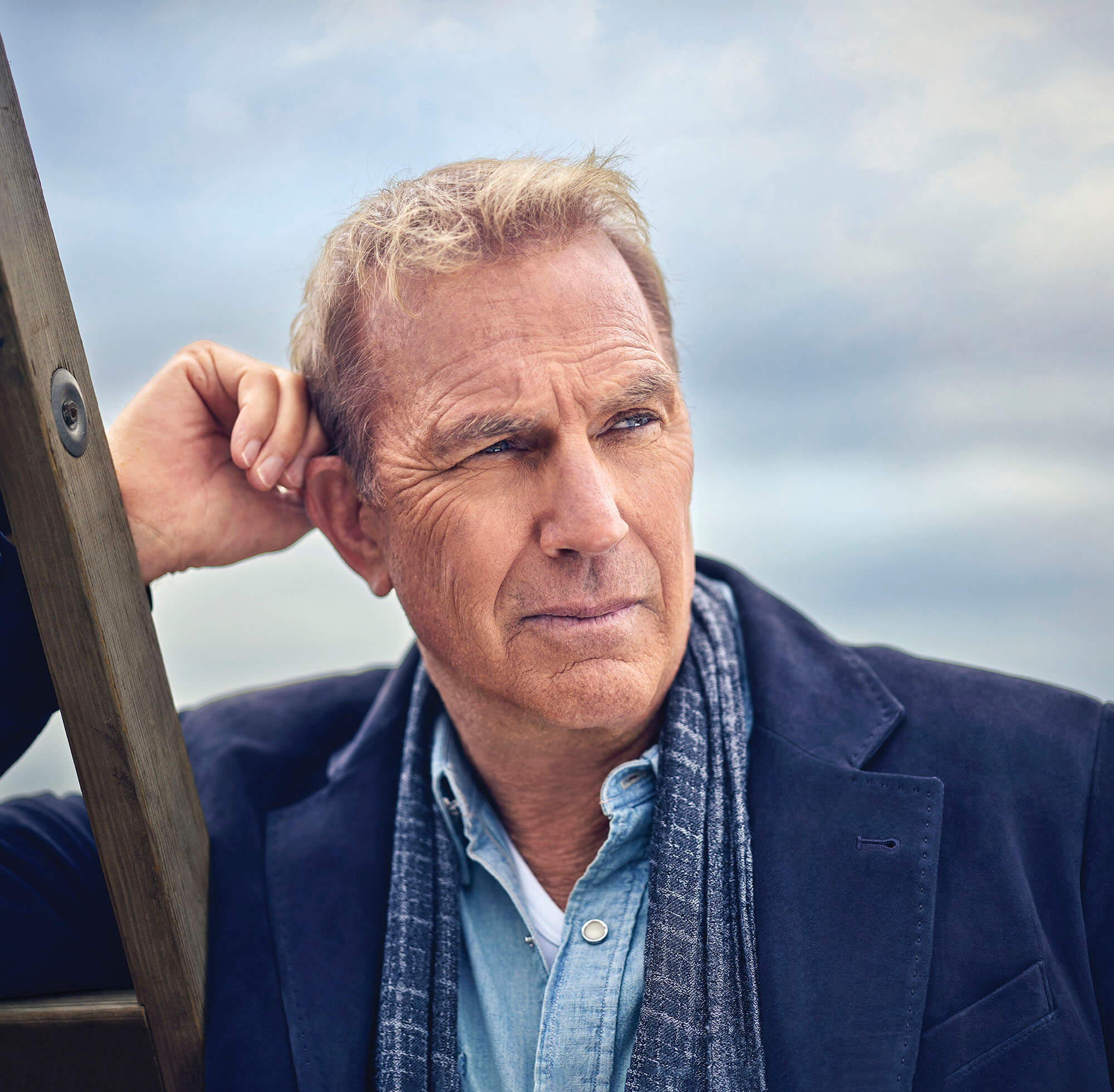

Kevin Costner, photographed for AARP in Montecito, California, on February 28, 2024

KEVIN COSTNER SPENT 36 years working to get his newest movie to its premiere this summer. He commissioned the original story, and he cowrote, directed, produced and will star in all four of the movies that make up another career-defining gamble, Horizon: An American Saga. He has even personally financed a significant portion of the series—to the tune of $38 million so far, plus a substantial deferred salary. “I pushed my chips to the middle and didn’t blink,” he says defiantly.

Just don’t refer to it as a passion project.

“Calling it that actually minimizes it,” he is quick to point out, as we sit in his contemporary, sparsely furnished guesthouse overlooking the Pacific near Santa Barbara, California. “I’ve been passionate about a lot of things that I’ve done. This is a good idea about America. People came west. It’s part of our legacy. I just believed in it so much that I put my money into it, but I’ve had that belief about everything in my life.”

Though Horizon is a mammoth undertaking, Kevin Costner knows what work is. His father was a ditchdigger and later serviced electric lines; his mother was a welfare worker, and Costner grew up in a series of then largely working-class California cities like Ventura and Visalia. After graduating from Cal State Fullerton, he drove a truck, led bus tours of homes of Hollywood stars and worked on fishing boats. “I worked as a deckhand, out of Eureka, Coos Bay and Newport,” he says, gazing at the sea. “We fished salmon and, late in the season, albacore. Sometimes we were out for eight days. The boat was only 28 feet, built in 1929, an old traditional boat, and we worked every day. That’s how I made my money.”

“I am also getting old. I have a shelf life and eventually I would be too old to make this movie that I really wanted to make.”

Hard work defined him then—and now. He has starred in more than 50 feature films and produced or directed over 30. He’s launched and invested in such diverse businesses as a casino in South Dakota, an oil-separation technology firm and numerous innovative start-ups. Meanwhile, he founded and fronted a country rock band, Kevin Costner & Modern West, which recorded several albums (one of them charted on the Billboard 200) and even toured Europe.

The inspiration to take on acting came during a chance encounter in 1978. While on a flight from his honeymoon in Mexico (with his first wife), a 23-year-old Costner reportedly noticed Richard Burton sitting in first class, surrounded by several vacant seats that Burton had purchased so that the other passengers would leave him alone. Costner waited for Burton to finish his book before he approached the great leading man, to ask him about a career in acting.

Burton looked him up and down. “You have green eyes,” Burton pointed out. “And I have green eyes. I think you’ll be fine.” Costner then asked Burton if it was possible to have a life in acting without the turmoil that Burton himself had experienced. “I think it’s possible,” Burton told him. “It hasn’t been for me, but I think it’s possible.”

That’s when the work was jump-started, by way of acting lessons and countless auditions. There were setbacks in the early ’80s (Costner’s role in The Big Chill was edited out of the final cut by director Lawrence Kasdan; ironically, Kasdan’s brother, Mark, helped cowrite Horizon), followed by some big hits in the mid-to-late ’80s—No Way Out, The Untouchables, Bull Durham and the still wildly popular Field of Dreams. [For more on Field of Dreams’ lasting impact, see “His Field of Dreams,” below.]

In 1990 came Dances With Wolves, the first big bet Costner made on himself. From the very start, he was all in on the historical Western; he played the lead role and was coproducer, director and even a financier of the film. It became a family affair when his daughter Annie made an appearance, the first of several young Costners to show up in his films over the years.

At three hours, the movie was thought to be too long for a modern movie audience. But he owned his choices. “I’m a ‘more is better’ type of director,” he said. “If something is good, I don’t want it to end.” Audiences agreed. Dances With Wolves grossed some $424 million worldwide (that’s approximately $1 billion in today’s dollars) and won the Oscar for best picture and best director for Costner (in his directorial debut). It was also credited with revitalizing interest in classic Western filmmaking in Hollywood, a legacy that Costner has clearly taken to heart.

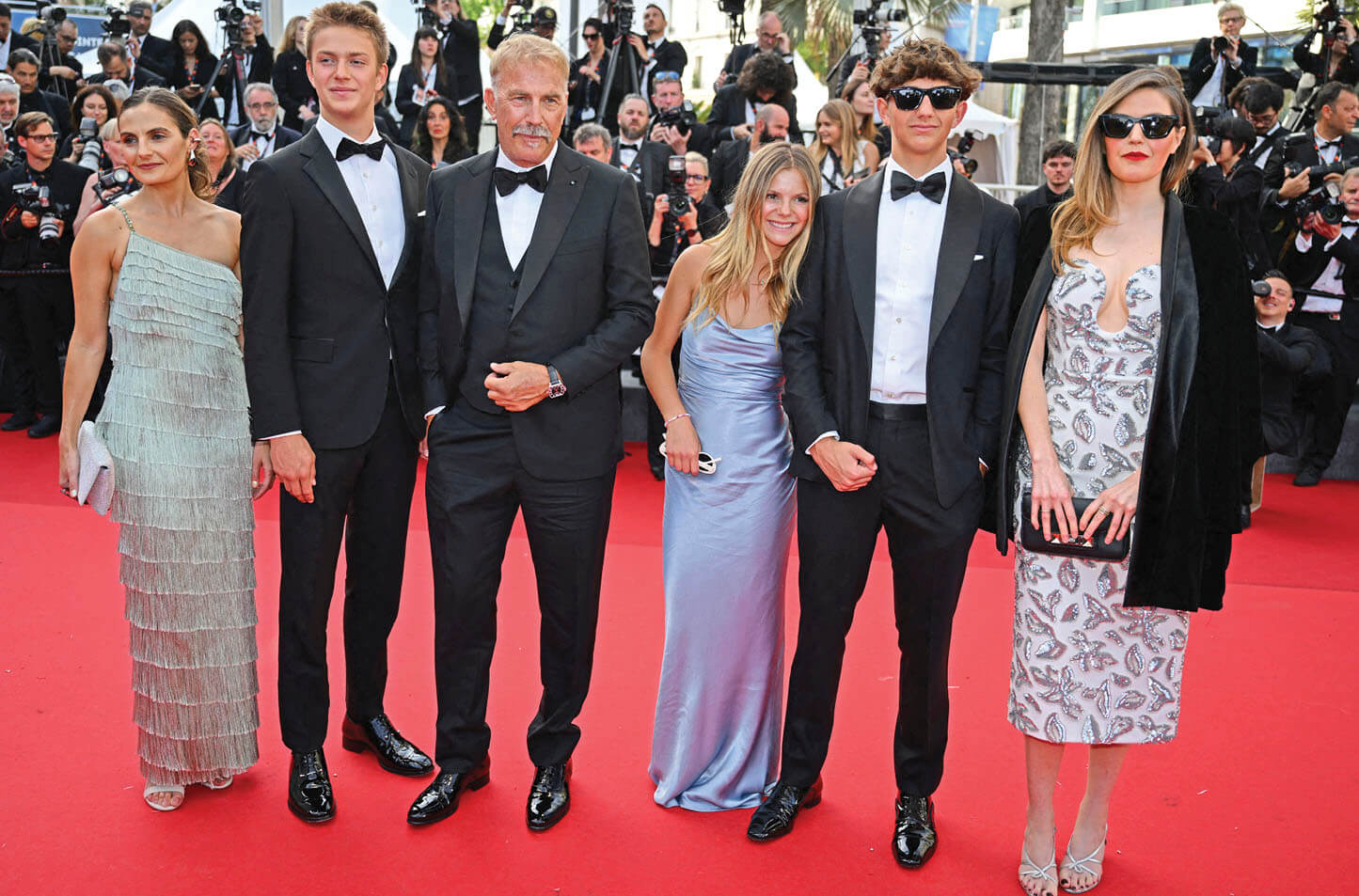

Kevin Costner, center, in Cannes with five of his seven children, May 2024

He went on to star in some hits in the ’90s, most notably JFK and The Bodyguard. (Of note: He recently revealed that he had been in talks with Princess Diana to do a sequel before her death in 1997.) And yes, some measure of the turmoil he once feared did follow, as he starred in and produced a couple of notable flops with which he is still famously associated—The Postman (which he also directed) and Waterworld.

There were other troubles from time to time—divorces, lawsuits and disagreements—all of it widely reported. Today Costner, 69, is fresh off his controversial departure from the TV series Yellowstone, which he left after production delays endangered the shooting schedule of Horizon. (Through the spring, Costner and the Yellowstone producers and showrunners publicly laid blame at each other’s feet for the abrupt ending, and in late June, Paramount announced production would resume without Costner. He then confirmed via Instagram that he was done with Yellowstone “into the future.”)

Now, having recently finalized his second divorce, he stands in the premiere moment of another massive career gamble—his unprecedented Horizon project, a story of the violent settling of the American West in the period before, during and after the Civil War. The first film is in theaters, with the second to arrive August 16 and the third already shot. Some early reviews were decidedly mixed, but Costner says he doesn’t read reviews. “Everybody says, ‘Well, it’s just water off a duck’s back,’ ” he says. “But it’s not. They can hurt.”

At the screening of Chapter 1 of Horizon in Cannes this spring, a teary Costner, with five of his seven children nearby—received an 11-minute standing ovation at the film’s conclusion. He’ll take it. “I’d heard that they clap for you there even if they don’t like it, which is kind of beautiful,” he says ruefully. “But as this went on and on, it got beyond that. I had visualized being in Cannes with a movie that was really, really important to me, and this movie became that movie—that response was everything I could have dreamed of. At some point I stopped hearing the clapping and began thinking back to the beginning of my career and the ups and downs, to retrace the breadcrumbs of my life. And when I came back from that, they were still clapping!”

Today Costner seems unvexed by the risk, turmoil, mixed reception or potential losses, though he manages to turn nearly every question back to his current obsession and bet-the-farm gamble, Horizon.

Q. Let me just start with Yellowstone. Was leaving difficult for you? I loved Yellowstone. I would have gone back and done it again under the right circumstances. I had a contract for Horizon, and the Yellowstone producers knew about that. The rug came out from under us because the universe they were creating got bigger [with Yellowstone prequels and sequels], and they just didn’t have the scripts for Yellowstone. That’s where the Yellowstone producers should have been clear with everyone involved and said: We need to get our scripts finished. I became this kind of flash point. I didn’t enjoy that it was mischaracterized. I had 300 people waiting for me in Moab, all of them ready to begin work on Horizon. I couldn’t leave them behind.

Q. Dances With Wolves was also a gamble. Have you always been someone comfortable with risk? I grew up in a conservative house and had a brother in Vietnam. It stalled my thinking for a time. My dad had one job, an electrician. He came out of the dust bowl. Growing up, there wasn’t really a time when I wanted to dissent, though at that time it seemed like the whole country was dissenting. For me to even daydream, that was code to my dad for “lazy” as opposed to, “I’m thinking about things. I’m thinking I can be something.” So it took me a while to find my own ground, to come to think I’d like to tell stories for a living, permanent daydreaming. And I’ve lived kind of like Huckleberry Finn, Tom Sawyer. I have built tree houses, floated down rivers, played hooky—and I found my own yellow brick road in storytelling. And that really threw my dad. He didn’t know how to help me, and I didn’t know how to explain it to him. Thank God I found my own way.

Q. Where did Horizon come from? I commissioned a script in 1988, and we kept fiddling with it and finally tried to make it in 2003. But I wanted more money than the studio was willing to pay. I was disappointed. After that I sat down with a new writer, and I became a cowriter. And we began to expand and reengineer everything. Out of that came these four screenplays.

Q. Four movies. Did people think you were crazy? It seemed so backward to Hollywood. They said: “Nobody wanted to make the first one. What makes you think they will want to make four?” But that’s me in a nutshell.

Q. What, that you’re stubborn? I just don’t fall out of love, and I loved the story. I tried again to get it made in 2015. And nobody would make it then, so finally, a few years ago, I just said, “I’m going to make it. I can’t wait any longer. I’m just going to do it.” Because I’m also getting old. I have a shelf life, and eventually I would be too old to make this movie that I really wanted to make.

Q. The movie is full of precise historical details. Where is that from? Is it from your own experience running ranches and small businesses in the American West? No, I just read books. I’m thrilled by details and the survival instinct that people displayed on the frontier. I love the spontaneity and the mindset of engineers in the era. Movie viewers are usually rushing toward the gunfight. But somebody had to plot these towns out. Somebody had to go out there with a shovel. Wheels broke down. And the way pioneers solved many problems elegantly, just ingeniously. I always like reading about that, and then I think, Can I fashion a story, a dialogue, around those facts?

Q. Women are often central to your storytelling, and that seems true again in Horizon, which stars, among others, Sienna Miller as a frontier wife. Women are not ornaments. They have a story. And I found it was easier to write about the story if women were embraced as the people that made the thing go. The West, where there’s no law, sets up for very dramatic architecture between good men and bad men, and the people that get caught in between are women. In the West, they were victimized, and often had no say in why they ended up out there. And so many women worked themselves to death just trying to keep their family clean and fed. I had to make this movie because those stories are as much a part of the West as the gunfight to me.

Q. You’ve cast several of your children in the movies you’ve directed. Your son appears in Horizon. What was that like for you? What I love about my children is they’re not wrapped up in what I do. Like any adult, I try to figure out ways for them to be with me. So, small roles. But my kids don’t know a lot about the acting business. I don’t draw them into it. My son was on the set, and I pointed and said, “That’s your mark.” He said, “What does that mean?” I had a bigger part for my little girl, but she turned it down. She said to me, “Daddy, I like the first day of school. I like meeting my new friends.” I love that she knew herself so well.

Q. You’ve put a lot of your own money into this project. Do you see it as more of an investment than a gamble? I did the same thing on Dances With Wolves. And when the money fell apart on [2014’s] Black or White, I paid for it. I’ve been lucky. I’ve been blessed. This is my guesthouse. Next to it is my house. And I have 10 acres that I haven’t built on. So, yes, I mortgaged all that to put money into Horizon. If I lose this house, am I a failure? Maybe I lost something in the making, but entrepreneurially, to not bet on this would be foolish; I wouldn’t do that. I don’t think my dreams are foolish.

Q. On another subject, how can you tell a good movie script from a bad one? It’s fairly simple. Writing is everything in Hollywood. I remember reading Field of Dreams and knowing beyond a shadow of a doubt that it was magical, that it had some gold dust on it. You have to see the moments in the script that would be a reason why someone would leave their house and pay for a babysitter. And I know that if I can hit those moments as a director and actor, then it’s going to be a fulfilling experience. Field of Dreams was full of those moments and so is Horizon.

Q. And how will you judge Horizon’s success? You know, I think we have false gods when it comes to how we judge success. I understand what it’s like to have a huge hit and what it does for you. And I would love for this to be supported, watched, shared, because I made it with that in mind. But what’s success? Is it money? Is it doing what you wanted to do in life? Movies aren’t just about opening weekend. Ten years later, a good movie will still be shared. Success is: Will you revisit it and show your daughter, show your son? Will you revisit it because you wonder about it, because you find new details? Those are the measures.

6 for 6

Six films in six years launched Kevin Costner to stardom

1987

The Untouchables

Ness vs. Capone. “They pull a knife, you pull a gun ... the Chicago way!”

1988

Bull Durham

“I believe in the soul … the small of a woman’s back ... the hanging curveball....”

1989

Field of Dreams

America’s pastime as mystical vision quest. If you build it, they will come.

1990

Dances With Wolves

Twelve nominations. Seven Oscars. Costner’s directorial debut: priceless.

1991

JFK

Oliver Stone revisits Dealey Plaza and jumps through the looking glass.

1992

The Bodyguard

KC to Whitney: Start the song a cappella. The rest is history. —Chris nashawaty

Tom Chiarella was a longtime writer for Esquire and is a National Magazine Award winner. He wrote AARP The Magazine’s cover story on Henry Winkler last year.

With additional reporting by Caitlin Rossmann

His Field of Dreams

Dwier Brown’s role of a lifetime

Dwier Brown

IN FIELD OF DREAMS, Dwier Brown plays John Kinsella, the father of Kevin Costner’s character, Ray. In the last few minutes of the movie (spoiler alert?), John—in one of the most poignant father-son moments in film—appears as a young man in a baseball catcher’s uniform and has a conversation, and a game of catch, with his full-grown son. The moment was seared into moviegoers’ hearts, and for Brown that bit part became a lifelong calling.

“He’s a very humble person,” says Costner of Brown. “And he’s been able to pivot on that film in a very graceful way.”

Here’s how it went down, in Dwier Brown’s own words.

My role in Field of Dreams was so small. I read all my lines during the audition and I remember thinking, Nobody is even going to notice this role. But 35 years later, strangers still want to tell me stories about their fathers because of that part. I feel like the film turned me into a kind of traveling priest, hearing confessions.

That scene really touches people. The movie is a great adaptation of a great novel, and by the end, Kevin and James Earl Jones and the other actors have opened the audience’s hearts. I just take off my catcher’s mask and walk right in.

The first time I really understood how important my character was to people was in 1989, about three months after the movie was released. A man approached me in a cramped corner store with tears in his eyes and said, “I can’t believe it’s you.” Then he told me that during the movie, he hadn’t been able to stop thinking about his father, to whom he hadn’t spoken in 15 years. At the end of the film, he had driven straight from the theater to his dad’s house to reconnect. Another time, a woman told me how she’d found out that her “uncle” was really her biological father. By the time we finished talking, we were both in tears. When these encounters happen, I love to be present and listen, and often we end up in an emotional hug.

Field of Dreams

As I get older and look less like I did when I was 29, I don’t get recognized as often. But sometimes when I do ballpark appearances, if a team is having a Field of Dreams theme day or something, there will be 50 people lined up to talk to me. I hear these incredible, tear-jerking stories from people. Maybe they had a hard time with their father, or maybe he’s gone and they miss him so much. I can relate: My own dad passed away shortly before we began shooting the movie. Whatever it is they want to tell me—or, rather, tell John Kinsella—it often seems like a burden is lifted from them, like I’m hearing something they are unable to say to anybody else. I just try to be the surrogate father that person needs me to be in that moment.

As a young actor, I had my own dream. I wanted to be a movie star, with a long career. And although I worked in Hollywood for 40 years, that stardom never happened for me. For a long time, I was a little embarrassed that this five-minute scene was the most memorable thing I had done. But now I look at it as something enduring, maybe more so than whatever other films I would have wanted to star in. —As told to Carolyn Campbell

Dwier Brown, 65, is the author of the memoir If You Build It...: A Book About Fathers, Fate and Field of Dreams and cofounder of the Baseball Hall of Dreams in Dyersville, Iowa, where Field of Dreams was filmed.