FROM OUR ARCHIVES

This is the third of AARP The Magazine’s four cover stories featuring Kevin Costner, from August/September 2020.

Kevin Costner would like a word…(with us)

Hop in the truck and let’s chat with this all-American leading man—as he chases ideas down rabbit holes, shoots the clichés out of westerns and pursues the best work of his career

KEVIN COSTNER’S LANDLINE IS RINGING.

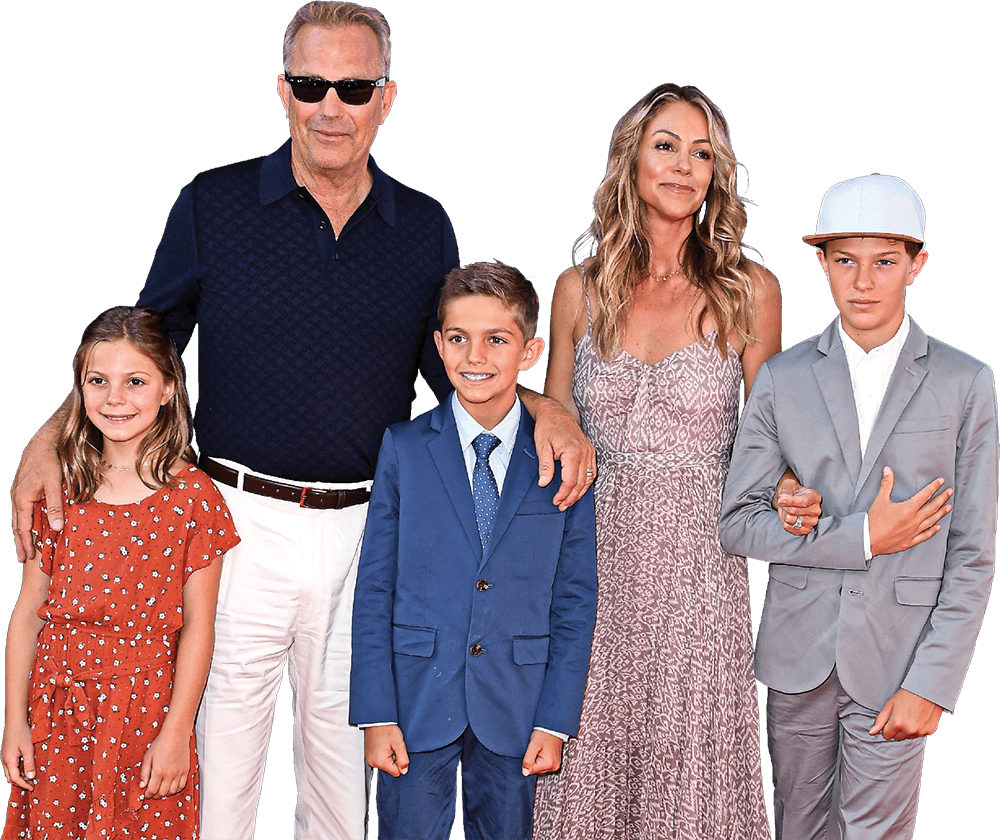

“I haven’t heard that phone in a century,” he says, chuckling. “I didn’t even know there was a phone in this room.” Costner, 65, has squirreled himself away in a home office for our call, carving out private space as best he can from his wife, Christine Baumgartner, and their three kids—Cayden, 13, Hayes, 11, and Grace, 10—all of whom are quarantining at their Santa Barbara home. Along with the retro trill of the ghost phone, the ambient laughter and chatter of a lively family fill the background air, accompanied by the persistent bark of at least one dog.

So it is during COVID-19, where work from home often means working around real life. Not that Oscar and Emmy winner Costner minds. Both as a creative artist and as a family man, he prefers the messy unpredictability of reality.

“Listen, the hallmark of a real conversation is how straight can we talk with each other,” he says bluntly, cutting through any formalities. Costner considers chitchat tiresome at best. He dislikes empty nonsense in his life, avoids it in his profession. Now more than ever, he prefers getting to the root, and says honesty is what makes “a thing worth doing.”

Costner broke out as an actor in the 1980s, after bringing surprising pathos to a string of leading-man roles in The Untouchables, Bull Durham and Field of Dreams. The streak continued with his epic, Dances With Wolves, a love letter to integrity that he directed and starred in—netting him Academy Awards for both. Ever since, Costner has gravitated toward authenticity, injecting his particular brand of accessible masculinity into the pop-culture bloodstream.

“I have a tendency to go down rabbit holes,” he says of his creative choices. That embrace of spontaneity and nuance—and, more critically, his faith in the audience’s intelligence and curiosity—is why Costner’s work, at its best, transcends cliché, even in the cliché-laden genres of westerns and sports narratives. His films linger in the public consciousness; his unfussy performances prick like the spines on a cucumber vine, unnoticed until they pierce your skin and lodge there.

As a working-class kid growing up on the margins of L.A., Costner understood the difference between fakery and truth, between pretense and character. He never forgot. His entrance into acting was steered not by a longing for fame so much as a hope for connection. Early in his career, Costner said no more than yes, argued over dialogue that rang false to his ear—ballsy moves that would have sunk lesser talents. He wasn’t worried. He was either going to succeed as he saw fit, or not at all. Accountability is bedrock for Costner. There’s a reason he’s played so many decent men.

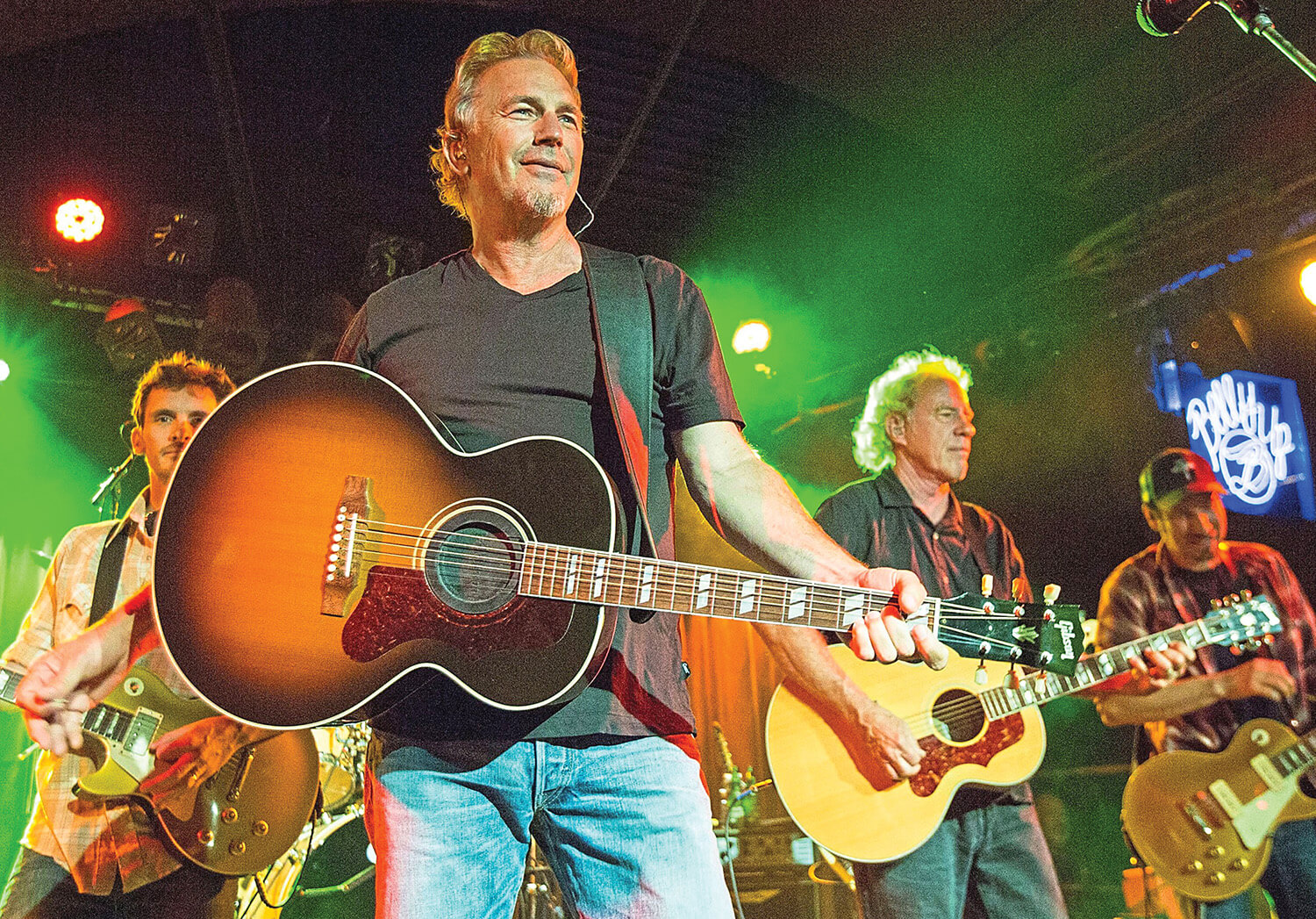

Costner’s country-rock band, Modern West, just released an album.

Any actor will tell you that embodying the good guy is far harder than depicting the villain. Yet Costner has given us both believable men and men to believe in.

“It’s not important for me to reinvent history or to set the record straight,” he says of his approach. Only for people to witness the full spectrum of humanity—good, bad and every shade between—and to find themselves within it. “I want people to think, That could have been me really easy. And if it were me, what would I have done?”

Costner relishes a moral quandary. This summer he’s returning to the screen as John Dutton, the patriarch of a ranching family, in Season 3 of the Paramount Network series Yellowstone. And in the fall, he'll play George Blackledge, a retired sheriff faced with an impossible choice in the elegiac western noir Let Him Go. In each role, Costner plays a deeply ethical man who, for better or worse, lives resolutely in the pocket of who he is. Much like the actor himself.

The actor with wife Christine Baumgartner and their three kids; he has four older children as well.

Q: We’re talking during a pandemic. What’s the biggest lesson you think we should take away from this time?

Government has to be anticipatory. Anticipating problems is the key to being a leader. I know that sounds like a simple word, anticipation, but that’s what we expect. Thoughtful leadership that does not involve ego, does not involve career extension, any of that. If you’re in public service, you can’t put yourself first. If you do that, that’s wrong.

Q: Do these concerns weigh on you as a parent?

Yes. I worry about all the things that go with being a provider. What if this doesn’t happen? What if this does happen? I’m a bit of a survivalist. I’m not a prepper, I’m not a hoarder, but it’s important to me to anticipate things going wrong and make the best move for my family, for my extended family and friends. I take that all on. Sometimes what you think you can protect is a bit of an illusion. But there’s a lot of problems that could be solved with common sense. About 20 percent of our problems may not have a solution. But 80 percent of our problems are manageable, and we just haven’t managed them.

Q: You have seven children [including three with first wife Cindy Silva and one with former girlfriend Bridget Rooney]. What do you want most to teach them?

I want my children to know I’m a resource to them, that I have been across the river a lot of times. I can tell them the rocks that move and the rocks that don’t. As a father, you don’t give yourself a badge or a medal for any of the things you do. In fact, your kids will probably be the first ones to tell you the things you haven’t done. And good for them. If they recognize that, that’s a bucket that they don’t have to step in themselves. I want to see what kind of people my kids become. I don’t care what they do; I want to see who they are.

Let Him Go

Q: Character.

That’s right. I think about Lincoln on that train ride to Gettysburg, penning his address and listening to that a--hole before him speak for over an hour and a half, who was just drubbing him. And then Lincoln sitting there, looking at his puny 270 words or whatever they were and thinking, Oh, man, I’ve miscalculated here. And it stands forever. Forever.

Q: What drew you to make Let Him Go, a dark western gothic set in 1951? You play a grieving father.

It felt honest. The western is not based on one person’s story. It’s based on something that probably happened thousands of times. The first western I did, Silverado, wasn’t history; it was good matinee fun. Later on, I did Wyatt Earp, which was more biographical. My western Open Range was based on a novel, yet the conflict it showed between free grazers and the people who were fencing in land with barbed wire could have played out a thousand times. Just because something is fiction doesn’t mean you can’t find yourself in it.

Q: Your new film explores the sacrifices parents make. Did you have a good relationship with your folks?

My dad was pretty tough. My mom was the one that let me know things were possible. I was a bit of a rascal, a dreamer. I remember stealing a piece of candy one time. I was 6 or 7 years old. Before we left the store, my dad said, “I think you need to put that candy back. Why did you take it?” I said, “I was hungry.” And he said, “It’s not yours, so the correct title is, you stole it.” His point was, you can justify anything. But if you put the correct title on it, it will help guide your decisions in life.

Q: You’re working on a big multi-film project.

I’m pushing the rock uphill. It’s four movies, all the same story, and it takes you to a place that you think you know, but you don’t. I have it in my pocket as a great big secret that someday I will let people in on, and hopefully, it will be something they never forget.

Q: Why is fighting for creative integrity so important to you?

I have been tested in a lot of different ways. There have been very critical moments where I had to listen to myself and act and not be afraid of the outcome. I always put the audience on my shoulder. And I will say to Hollywood people, “Don’t be too sure they don’t want to see that.” And that’s what the fight is about. I haven’t always been really successful in certain movies. But I still love it.

Q: You and your country-rock band, Modern West, have recorded an album called Tales From Yellowstone.

I grew up singing and playing music in the church, so that was my first love. The first band I was in, I was in my 20s, and it was called Roving Boy.I was emerging as an actor and I got a terrible review, and it really shocked me. I thought to myself, Do I need this kind of scrutiny? You know, the actor playing music. So I stepped away.

Q: What got you back into music?

My wife, Christine, discovered that early music and asked me, “Why don’t you do this?” And I said, “Oh, no, no.” For two years I backed away from it. She asked, “Are you happy when you’re doing it?” And I said, “Yeah.” And she goes, “Do you think the people in front of you are happy?” And I said, “Yeah.” And she just looked at me and said, “Well, what could be wrong with that?” So I called up two members of that original band. We’ve been playing together for the last 16 years.

Q: What do you wish that you were better at?

Getting it right.

Q: It seems you’re getting a lot right.

Yeah, but those things you don’t, they can really foul you up. [Laughs.] I plan to play out the second half of my career with big movies that have a level of poetry. There’s a perception out there that I can do whatever I want, that things get easier for me professionally with age. It’s simply not true. It’s just as hard to make things now as it was when I was trying to make Dances. But I should do whatever I want. I’m at that spot in my life, artistically. I should be doing what pleases me.

Q: Are we still talking about making movies?

A movie is just something for us to grasp in the dark, just watching and going, Hmm, I didn’t expect that. I’m glad I saw that. And then you’ve got to move on to the rest of your difficult day. But I want to be a part of that moment. What we yearn for, we all yearn for. I know that in my heart.

Western Star

Costner’s career on the range

Silverado (1985) A 30-year-old Costner plays Jake, a misfit cowboy who joins his brother on a journey to a troubled town.

Dances With Wolves (1990) Costner stars as a Civil War lieutenant who develops a bond with a tribe of Lakota. He won the Academy Award for best director.

Wyatt Earp (1994) In the title role, Costner portrays the legendary lawman torn between his live-by-the-code career and loyalty to his family.

Open Range (2003) Playing a cowhand, Costner helps drive a herd of cattle across Montana. When one of his fellow cowboys is attacked, vengeance ensues, resulting in a long shootout finale.

Yellowstone (2018–now) As a powerful rancher in this neo-western TV series, Costner must defend his land against developers, an Indian reservation and the first U.S. national park.

Let Him Go (2020) Costner stars as a retired sheriff who, with his wife, sets off to rescue his young grandson from a nefarious family. Opens this fall. —Emily Paulin