BONUS CONTENT/FEATURE STORY

Connie Chung’s Big Break

In an excerpt from her new book, Connie: A Memoir, the former news anchor, now 77, reveals that her move toward the news anchor desk came from a push for diversity at CBS more than 50 years ago

Anchoring on election night 1992. Left: Dan Rather. Right: Bob Schieffer.

On October 1, 1971, I jumped into an ocean, having barely learned to tread water. I had been in the news business all of two years and on the air as a reporter for only one of them. Yet I was hired by CBS News, the most prestigious nationwide television network, led by the most trusted man in America, Walter Cronkite, the television anchorman I worshipped. Since no women anchored hard news, I had chosen Cronkite as my role model. I wanted to be just like “Uncle Walter,” as he was known across the nation, the man my family and millions more tuned in to watch religiously every evening.

The Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) was an empire created by William S. Paley, who was described by the New York Times as the personification of “power, glamour, allure and influence.” He and his fashion icon wife, Babe, were the darlings of New York high society.

Paley was still chairman of CBS when I arrived at his doorstep. It was a thrill to meet the pioneering figure and his legendary right-hand man, Frank Stanton, president of CBS, who championed First Amendment rights on behalf of the entire television news industry. Whenever Washington tried to interfere in what television news was reporting, Stanton would eloquently testify on Capitol Hill, a stalwart defender of freedom of the press. I had only read about these legends in newspapers, and now I was working for them. These were the glory days of broadcast news. CBS was called the Tiffany Network because it established the gold standard in entertainment and news. That’s because Paley created a ratings juggernaut in prime time with shows that hauled in the money, like I Love Lucy, Gunsmoke, All in the Family, Playhouse 90, and The Jack Benny Program. He once told the CBS star correspondents at a dinner, “Don’t worry about that”—meaning cost. “I’ve got Jack Benny to make money for me. You guys cover the news.” Paley’s shows provided the profits. His news division gave him prestige.

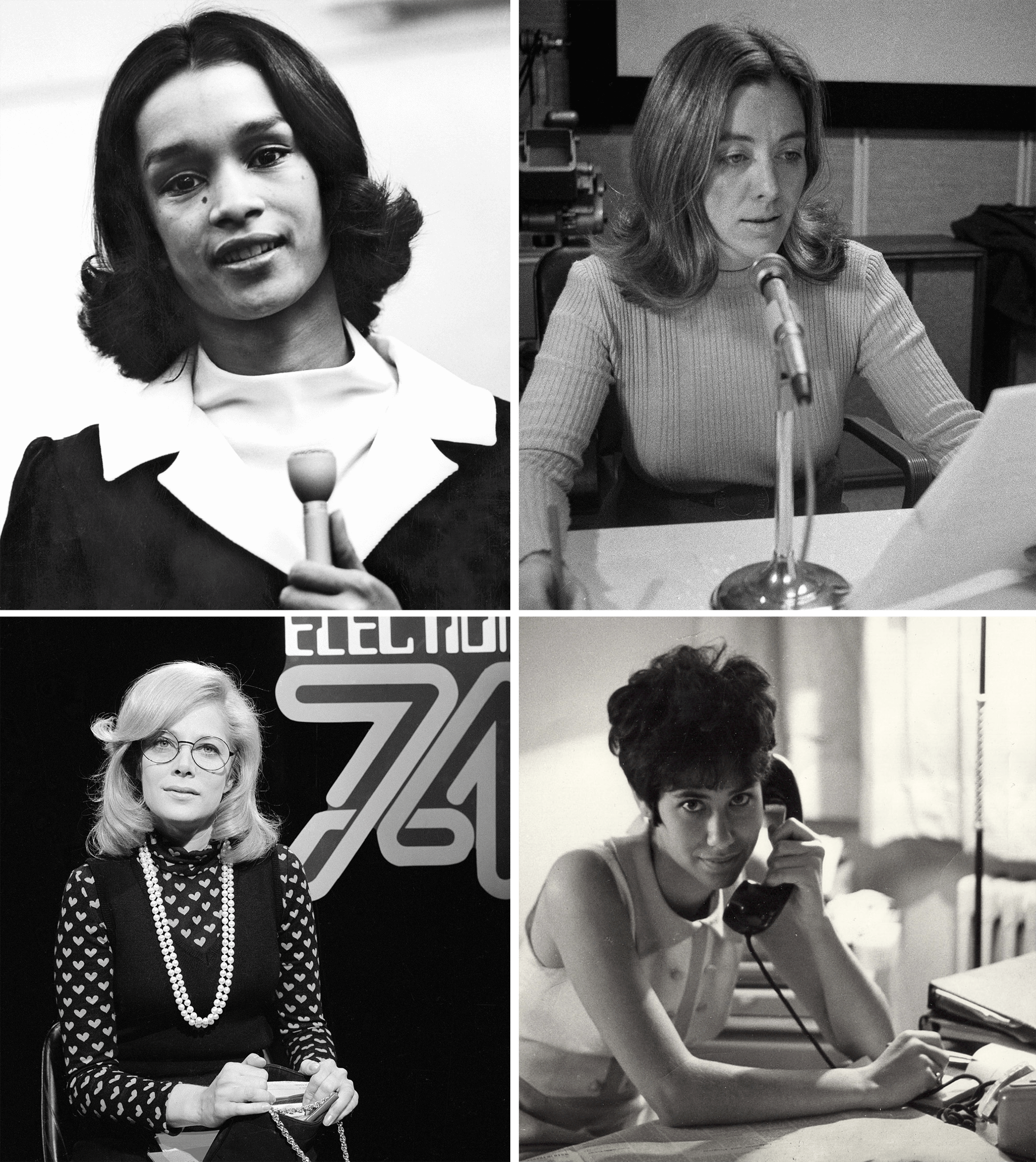

Clockwise from top left: Michele Clark; Sylvia Chase; Lynn Povich and Lesley Stahl

How did I get to plant my feet in this wonderland of respected journalists, where my idol Walter Cronkite was the lovable, trusted king? It was a dream that came true because of timing, a connection, and who I was—a woman and a minority.

Let’s start with the Civil Rights Act, signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson on July 2, 1964, “the most sweeping civil rights legislation since Reconstruction,” as the National Archives put it. The act outlawed discrimination in hiring because of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. It also created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to hear grievances and to correct them.

Aspiring women writers at Newsweek magazine, including my future sister-in-law, Lynn Povich [the journalist Maury Povich’s younger sister], took advantage of this new opportunity to redress inequities in their workplace. They were fed up with being relegated to jobs as researchers while men with the same experience were hired as writers, reporters, and editors—and, of course, paid more. As researchers, the women gathered the information only to turn their hard work over to the men who would write the stories. The most frustrating barrier for Lynn and the other women was that they were barred from ever being promoted.

In March 1970, Lynn and her fellow researchers met secretly in the ladies’ room, hired a lawyer, and filed a class-action complaint with the EEOC. The sixty women who signed the complaint won a huge victory that ultimately led to Lynn’s hiring as Newsweek’s first female senior editor in 1975. She later wrote a book, The Good Girls Revolt, about the groundbreaking Newsweek case.

Women at Time, Fortune, and Sports Illustrated followed Newsweek’s lead, filing complaints the same year. Widespread news coverage goaded companies across all industries to rectify years of discrimination against women in the workplace. Even on Capitol Hill, the stodgy U.S. Senate upended a 150-year tradition and hired women as Senate pages for the first time since the 1820s.

CBS News executives knew they needed to bow to civil rights groups and women’s pressure groups. Washington Bureau Chief Bill Small was one of the first to take preemptive action. Bill was a tall man with a quiet voice and hunched shoulders. His posture reminded me of a popular television host from my youth, Ed Sullivan. I was nervous as I arrived at his office with my résumé. But I shook it off with my spunky attitude: “Yes-I-don’t-have-a-lot-of-experience-but-I-learn-quickly.” Small asked me to write a short newscast to deliver from a tiny studio. Emerging after my momentous audition, I found him laughing out loud, guffawing at my amateurish delivery. Despite that, he hired me. I don’t know how that was possible, but I was one happy person. If this job turned out to be the one and only job I ever had, I would be just fine. I had hit the jackpot.

Covering first daughter Tricia Nixon’s Rose Garden wedding on White House South Portico lawn, June 12, 1971.

At about the same time, CBS News diversified in one fell swoop, quickly hiring three other women in every permutation and combination: Michele Clark, who was African American, based in Chicago; Lesley Stahl [the now longtime 60 Minutes correspondent] joined me in D.C.; and Sylvia Chase [who went on to become a mainstay 20/20 correspondent] in New York. We were a quartet of “affirmative action babies,” as Lesley called us. Those old guard goats at CBS News probably thought, “Phew, we are done.” Indeed, it wasn’t until a full decade later that CBS hired another new wave of female on-air reporters.

For me, every day was a test. Would I measure up? My being a woman was a bigger challenge than my race. I wanted to be accepted and treated just like my male colleagues when we all covered the male-dominated world of politics at the White House, Capitol Hill, the Pentagon, and the State Department. Everywhere I looked, there were men. Since I wanted to fit in, I became one of them. In my mind, I could walk like them, talk like them, and be as tough as they. Why should I perceive myself differently?

How did the women who’d preceded me navigate the boys’ club? It was complicated for me; I couldn’t imagine what it was like for them. Still, it never occurred to me to call them and ask for their wisdom. I admired Barbara Walters; NBC’s Pauline Frederick, the premier United Nations correspondent; ABC’s Marlene Sanders; and Nancy Dickerson, the first female correspondent at CBS News. But who had the time? I assumed they were overloaded doing their all-consuming jobs. I myself was overwhelmed, trying to keep my head above water.

I was on the job only five days when I made my first appearance on the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite. It was October 15, 1971. I was sent to cover a congressional hearing that was not expected to be newsworthy. The surgeon general had recommended using phosphate detergent even though it would pollute the environment. But at the hearing, his subordinate dropped a surprise on his boss, directly contradicting him. That was news.

As I rushed from Capitol Hill to the bureau, my heart was racing. Fortunately, Bob Mead, the evening news producer assigned to work with me, was calm, but we both knew there was no time to waste. We were on deadline.

A 25-year-old Connie Chung at CBS News, Feb. 8, 1972, Washington.

Bob and another producer, Don Bowers, chain-smoked and joked about sex. I thought all their sexual innuendos were funny, and I cheerfully played along—topping them with sassy, badass replies. There was nothing sinister about their banter, nor mine. Today, some would probably find it inappropriate in the workplace—but honestly, in those days, it was normal and cut the deadline tension. As we worked together, it was clear they were helping me hone my reporting, writing, and producing skills. They knew I was green, and they genuinely wanted me to succeed. I didn’t care about the remarks. I cared about my work and the final product.

Bob viewed the film and recommended a structure for the minute-and-fifteen-second story. I broke a sweat as I sat down at one of the manual typewriters in the newsroom, trying not to panic. Anxious, I couldn’t think clearly to write my script. “I can do this,” I assured myself. When I looked back at that script as part of my research for this book, I was shocked! I had written: “Should housewives ignore the danger to the environment and use phosphate detergents?” Oh my word! Sure, it was 1971, but was I really thinking like a Neanderthal? Only women—“housewives”—use detergent? Shame on me.

I was about to go to a small studio in our CBS News building to record an on-camera portion of my story when I was stopped by the producer, Bob Mead. My shoulder-length hair was tightly hair-sprayed into a bun, an attempt to look older and more serious. Bob suggested I take the bun apart and wear my customary teased flip. I am convinced he thought that since it would be my first exposure on national television, I should not look like Marian the Librarian. He may have envisioned I’d pull one bobby pin from my head and give my head a shake and my hair would fall to my shoulders in sexy slo-mo, a cascade of soft curls, just as in those L’Oréal commercials.

It was the first and the last time anyone suggested what I should do with my hair or clothes. Thank goodness, because I would not have taken kindly to that. Yet it was common for viewers to scrutinize a woman’s appearance on the air, while men were allowed to be bald, fat, and ugly!

Our story done, I settled into a chair in the newsroom. Every night, all of us in the CBS Washington bureau would gather to watch Walter’s newscast together. Cronkite’s nightly newscast started with what we called a ticker. The sound of the rat-a-tat newswire machine was accompanied by a baritone voice that announced, “This is the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite.” And as the voice intoned the name and location of each correspondent who would appear that night, the name was typed on the screen as if on ticker tape. It was a thrill that first night when I saw and heard, “Connie Chung in Washington.” I was only twenty-five years old. After my story aired, everyone in the newsroom applauded, even the star correspondents. How sweet it was.

Adapted from Connie: A Memoir by Connie Chung, published on Sept. 17, 2024. Copyright © 2024 by Connie Chung. Used by arrangement with Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.