FEATURE STORY

The Vietnam War was nearing a painful end 50 years ago.

But the war that divided a generation also provided stories of the sacrifice and courage of the roughly 2.7 million Americans who served there.

Veterans of the fighting in Southeast Asia are in their 70s or older now. They endured disdain after returning from the war, and many have wrestled with physical and psychological problems since, ranging from exposure to Agent Orange to post-traumatic stress disorder.

As a Veterans Day tribute to those who served in Vietnam, we’ve talked to some of the bravest of the brave—the 268 men who received the Congressional Medal of Honor for extraordinary gallantry. We also examined what life has been like after the Medal of Honor. While their deeds are exceptional, their lives reflect much of what happened to the men and women who answered the call to serve in Vietnam.

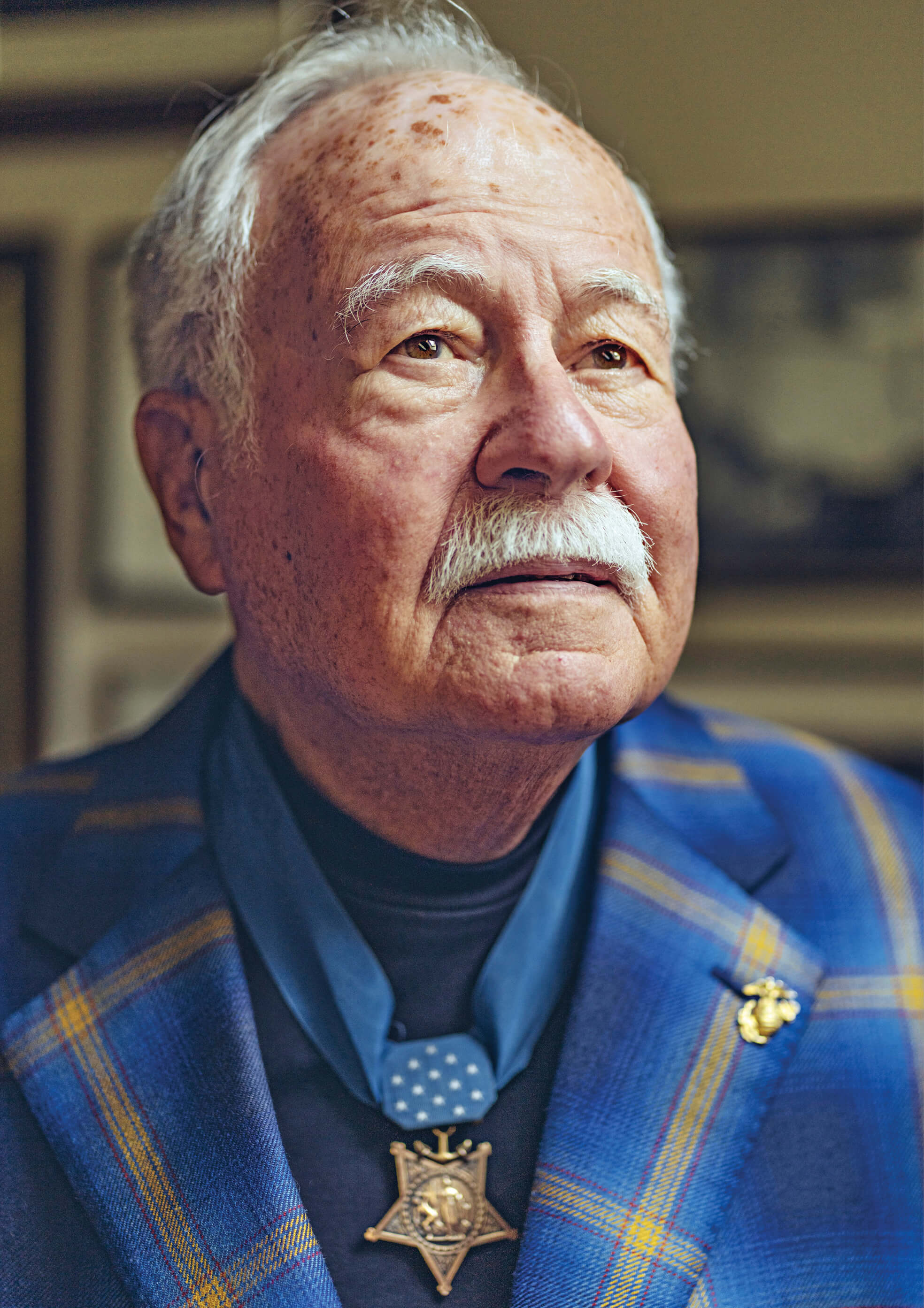

“I Had to Go Get My Brother”

Sammy Lee Davis, 77

Indianapolis

I WAS BORN in Dayton, Ohio. My dad was in the military. I joined the Army in 1966, and I remember stepping off the airplane in Vietnam. It was nice and cool in the plane, and it was 100 degrees outside. Stepping off the airplane, we soldiers looked at each other in amazement.

On the night of November 18, 1967, I was with Battery C, 2nd Battalion, 4th Artillery, 9th Infantry Division, patrolling a firebase. We were told we were going to get hit that night, and the battle started at 2 a.m. There was a river, and we saw the enemy coming toward us on the other side, shooting at us. The Viet Cong fired an RPG [rocket-propelled grenade] to hit our cannon, and the explosion threw me, unconscious, back into my foxhole. They thought I was dead. My ears were ringing, and I couldn’t hear much. When I came to, I could see the enemy running toward me, and I did my job as a soldier. I picked up my M16 and started firing.

That’s when one of our guys, Wendell Holloway, of Stockton, California, waved his hat at me from the other side of the river, shouting, “Don’t shoot, I’m a GI!” He screamed, “Come get me!” My back was broken, my ribs were crushed and I’d been shot in the right leg with an AK-47. But I had to go get my brother, because he would have done the same for me. I swam across the river, and when I got there, there were three men—not just Wendell—all wounded, one unconscious. I used an air mattress to help get us all back to the other side. I dragged everyone back across the river, and when I got there, my guys helped get everyone out. We all survived.

Davis getting the Medal of Honor from President Lyndon B. Johnson

When I woke up in a hospital in Japan, I’d been unconscious for a few days. General William Westmoreland was standing beside my bed. He had some 30 beehives [pieces of shrapnel] in his hand that a surgeon had removed from my body. He said, “Son, we’re going to retire you from the Army and send you home.” But I didn’t want to go home. General Westmoreland understood. I needed closure—I needed it for my soul to be OK. So I went back to Vietnam.

I set foot back on American soil on March 13, 1968. You have probably seen footage of the ceremony when I received the Medal of Honor. In the movie Forrest Gump, when Forrest is receiving his medal, that is my actual film footage. They put Tom Hanks’ face over mine. Every time I see Forrest Gump, it brings back memories.

I have often told people that if I hadn’t received the Medal of Honor, I’d probably have become a cow thief or something. In other words, I probably would have been doing bad things. But because of the Medal of Honor and the respect that I have for it, I didn’t want to do anything that would cause disrespect to it. It kept me doing right. In fact, when I learned that I was going to receive this medal, I thought right then, I’m going to have to be good. And I started trying to do better and better at everything I did. It worked.

After three years in the Army, I was medically retired. I couldn’t do anything without hurting really badly, but I knew I had to have a job. I went to work for Champion Laboratories in West Salem, Illinois, a company owned by Andy Granatelli, who was a great man. I don’t believe he was a veteran, but he acted like he was a veteran. [Readers may have heard of Granatelli, who was a legendary race car driver, CEO of STP and a major sponsor of Indianapolis 500 race cars.]

At the same time, the Medal of Honor has become a way of life. It’s a brotherhood. We all know what each other went through, and we encourage each other to stand up and be proud. The Medal of Honor has taught me how to express love for America and love for our fellow man.

I wear the medal when I am doing speaking engagements. I try not to preach politics, but I want every American to stand up for what they believe is right in their heart. I always open up to questions and answers, and I have found that I enjoy that most of all, especially when I am speaking to schools. There are some great questions you get from 10-year-olds.

When people ask me how the Medal of Honor changed my life, the first thing I say is that it kept me doing right my whole life, staying straight. It made me stand taller and walk prouder, always. Whenever I talk with people, I tell them the same thing: No matter what you’re faced with, you don’t lose until you quit trying.

African American Green Beret Finally Receives the Highest Honor

Paris Davis, 85

Alexandria, Virginia

THE SPECIAL Forces was fairly new at the time. It was a small group, formed to be the eyes and ears of America in battle, and to help keep us safe. When I started my training, I had already gone through Army Ranger and Airborne school. Earning my way into the Special Forces was no bowl of cherries.

We did a lot of classroom work, we jumped out of airplanes, and we did all kinds of things with weapons. A lot of people did not like the idea of me joining the Special Forces, and they were hoping I wouldn’t make it. But I wouldn’t back away. The more I did to prove that I could make it as a Green Beret, the stronger I became, the more friends I made and the easier it became. According to an article I saw in The New York Times, I was one of the first Black soldiers in the Special Forces.

In the spring of 1965, I was 26 years old and stationed in South Vietnam. We found out that there were a couple of places where the Viet Cong were sending troops down to about 25 kilometers from where we were located. We were going to have a showdown. The big battle at Bong Son was the result. It lasted a little over two days—mainly June 17 and 18, 1965.

I was with the 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), 1st Special Forces, and the commander of a small operation called Team A-321. There were four Americans in that operation—myself and three others. We were there training a force of local volunteers from Vietnam. The battle was on. According to my official citation, “Captain Davis’s advice and leadership allowed the company to gain the tactical advantage, allowing it to surprise the unsuspecting enemy force and kill approximately 100 enemy soldiers.”

Following an ambush, I had a situation where I went out to get three of my fellow Special Forces soldiers who got spread out and bring them back to safety. [Also from the official Medal of Honor citation: “Captain Davis constantly exposed himself to hostile small arms fire to rally the inexperienced and disorganized company. He expertly directed both artillery and small arms fire.... Although wounded in the leg, he aided in the evacuation of other wounded men of his unit, but refused medical evacuation himself. Then, with complete disregard for his own life, he braved intense enemy fire to cross an open field to rescue his seriously wounded and immobilized team sergeant.”]

We fought hard for two days before we could put this behind us. I was shot up pretty bad, and I was in the hospital for a long time. I never asked any questions; I just let them take care of me.

Meanwhile, my fellow soldiers and others were concerned about what had happened at Bong Son, and they took it upon themselves to come together. While I was in the hospital, I didn’t know “s--- from Shinola,” as the saying goes. But people on my team made a big to-do about it, and I was nominated to receive the Medal of Honor.

What happened next will surprise you. It certainly surprised me. I don’t want it to sound like braggadocio, so please don’t take my words that way. I was awarded two Purple Hearts, the Silver Star and any number of other medals. But the government lost my Medal of Honor paperwork—not once but twice. How did it happen? That’s a question I have been asked many times. I don’t know! Don’t ask me, ask the government. When you find out, we’ll both know. But there was a lot of hullabaloo, and people on my team went to Congress. They wrote letters and did whatever they could to let people know.

When I received the Medal of Honor in the White House on March 3, 2023, it changed my life in many ways. But number one is, it changed the [perception] of people that I knew. Because so many people I knew did not understand what had happened at Bong Son. When they had a chance to read and hear the whole narrative as it is stated in my Medal of Honor citation, then they could understand—not just my story but the story of the people that were there with me. They knew that we had done something that was extraordinary.

Second, I invited people to be there that day. People who had trained with me, and families of soldiers. That day in the White House, the “I” became “we,” and the “we” became “us.” And it continues.

I will tell you, from my point of view at this time in my life, we have some great guys and gals in the military today. Just top-drawer. I think America should pay homage to the people in our military, who are willing to go out there and stick their thumb in the air to see which way the wind is blowing, to make sure that America remains free.

Paris Davis’ book Every Weapon I Had will be published by St. Martin’s Press next June.

A Marine’s Hell Commences a Storied Career

Harvey “Barney” Barnum, 84

Reston, Virginia

IN DECEMBER 1965, I was attached to the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines, as part of Operation Harvest Moon in the Que Son Mountains in Vietnam. On December 18, the enemy—well camouflaged and well dug-in—picked out our company commander. He had a map in his hand, and his radio operator was behind him. The enemy aimed, and all hell broke loose.

I hit the deck. This was the first time I’d ever been shot at. I looked up and all these young Marines were looking at me. I’d only been with this company for about four days, and they didn’t even know my name. But I had a lieutenant’s bar on my collar, and they knew: Officers give orders, and Marines follow.

These young Marines were scared. Anyone who says they’re not scared when they’re getting shot at is lying. We realized that not only were we ambushed, we were nearly surrounded.

I ran out and picked up our captain and brought him back to a more secure area. He died in my arms. I realized the radio was out there, and I was going to need it. So I ran out and took the radio off the dead radio operator. I strapped it on and contacted our battalion commander. Ultimately, the battalion commander told me, “You have to come out of there. We can’t come get you.” The battalion was fully engaged in the village of Ky Phu. “We’re in one hell of a fight,” I was told. “So if you can’t come out yourself, you’re in there by yourself tonight.”

There was no future in that. If we stayed into the darkness, the enemy was going to finish us off. It was starting to get dark, and we had to move fast. I had engineers blow down some trees to clear a zone for helicopters to land. We put the dead and wounded on the helicopters. We had a medic named Doc Wes, and he was wounded. But he refused a shot of morphine, and he guided us on how to treat the wounded. He was the last one on the helicopter. As we put him on there, he was shot for the seventh time. Years later, I found out that he lived.

Those of us on the ground got ourselves organized, and I called in an airstrike against enemy positions. Ultimately, I told a group of Marines, “When you start going, you run as fast as you can, and don’t stop unless someone gets shot. If someone gets shot, you pick him up and keep going, because Marines don’t leave anyone on the battlefield.” It took a long time, but I got my Marines out. We were fired at all night long.

I received the Medal of Honor in 1967. I was told that the White House did not want to present the medal, and I believe it was because the Johnson administration was getting so much bad press over the war. I was decorated by the secretary of the Navy, Paul Nitze, in a ceremony in Marine barracks in Washington, D.C.

I was the first Medal of Honor recipient to go back to Vietnam. I was a professional Marine, and there was a war going on. I felt that was my duty and that was where I belonged.

I would be naive to think that the Medal of Honor didn’t help me in my career. I served in the military for 30 years and always tried to use the medal as a platform to continue serving. I traveled the country, speaking to students, American Legion posts, all kinds of audiences. I took every opportunity to let people know how fortunate they are to live in the greatest country in the world, but also to tell them that freedom isn’t free. You have to work for it, you have to contribute.

Before I retired, I had the privilege of serving my country as a deputy assistant secretary of the Navy. I have had a Navy ship named after me—a destroyer. I have met sports stars, movie stars, kings and queens. None of that would have happened without the Medal of Honor. But the most important thing has been the opportunity to keep serving my country. When I retired from the military, I continued talking to audiences. To me, it is a chance to remind people—if they need reminding—that we live in the greatest country on Earth.

A.J. Baime is a regular contributor to The Wall Street Journal and AARP publications and is the author of several books on American history and the auto industry.

THE MEDAL OF HONOR AT A GLANCE

Here are some facts about the Medal of Honor.

★ There were 1,523 Civil War recipients; 126 medals in World War I; 472 in World War II; 146 in Korea; 268 in Vietnam; and 28 in Iraq and Afghanistan.

★ One woman has received the medal: Mary E. Walker, who treated wounded soldiers in the Civil War.

★ Nineteen men have received two Medals of Honor.

★ Two sets of fathers and sons have won the medal: Theodore Roosevelt and his son Theodore Roosevelt Jr., and Arthur MacArthur Jr. and his son Douglas MacArthur.

Find out more about the Medal of Honor and read citations for the recipients on the Congressional Medal of Honor Society’s website at cmohs.org.