Failure is the New Success

What quality do bosses look for most in an employee these days? A willingness to fail — big. Fail fast also means learn fast and succeed more

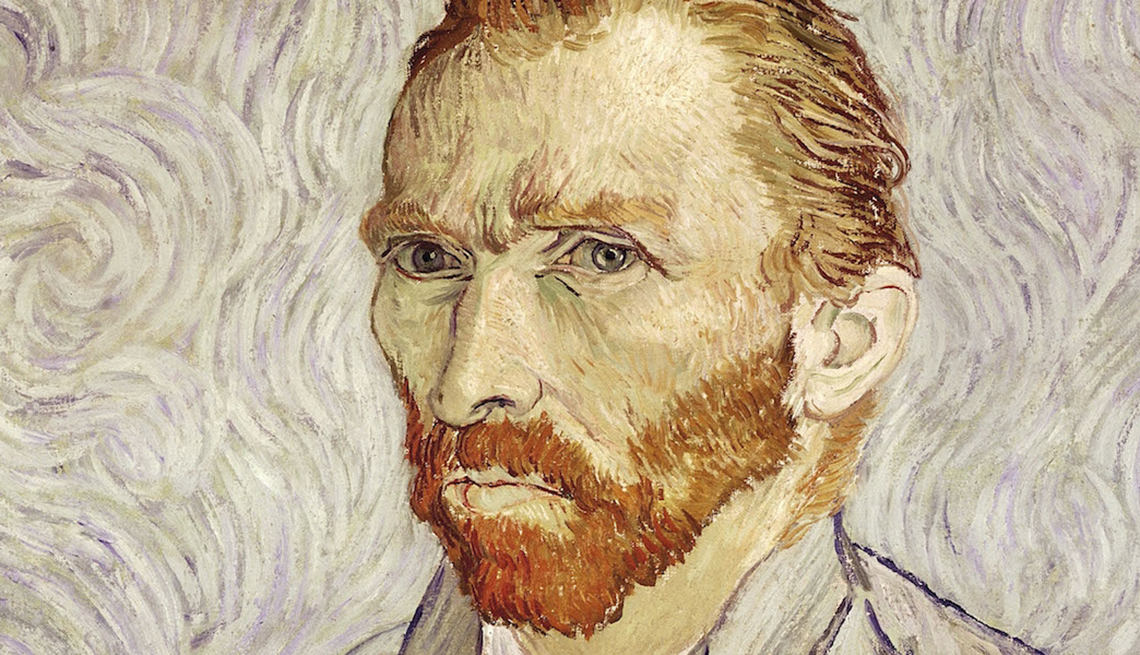

Einstein was a failure. He was also preternaturally brilliant, a rare quality we assume should have shielded him from the Average Joe method of trial and error. Au contraire. In explaining his success, the man who was determined to puzzle out the theory of relativity admitted that he wasn’t necessarily any smarter than most, but that he “stay[ed] with problems longer.” It took eight years and one failed experiment after another before Einstein scored his win.

While serendipity sometimes plays a role in unearthing new theories or knowledge (or coming up with the next killer app), these epiphanies generally come as a result of eliminating what doesn’t work. In other words, before you can “discover” the theory of relativity, you’ve got to first eliminate all the wrong approaches. Sounds exhausting, doesn’t it?

So, what do you think? Do you have an Einsteinian tolerance for the chance of crash-and-burn inherent in all creative endeavors? Not everyone does. But the good news is, it can be developed. Then read on to learn how to turn major mistakes into superstar successes.

How Do You Define Success?

Today’s most innovative leaders are eschewing the mindset that discourages employees from taking risks that lead to big rewards, and they’re leading by example. Bill Gates insists that successful innovation and success in general is often built on learning from failure, and he hires the smartest people he can find who have a bias for action; action that sometimes results in failed attempts while pursuing grand ideas. Arianna Huffington co-founded The Huffington Post to decidedly mixed reviews, one referring to it as “the equivalent of Gigli, Ishtar and Heaven’s Gate rolled into one.” Undaunted, Huffington’s bias was to try it. If it doesn’t work, move on to the next idea. Richard Branson of Virgin, Kathryn Minshew of The Muse, and Mark Zuckerberg at Facebook—all these game changers promote the idea that nothing innovative comes from playing it safe.

Bouncing Off a Brick Wall

But perhaps no leader has promoted well-intentioned failure with the zest of Kyle Zimmer, CEO and co-founder of First Book, a nonprofit that partners with publishers to ensure disadvantaged children receive first-run, first-rate books throughout their early childhood years. Zimmer created what she calls the Brick Wall Award, an honor bestowed upon employees who pursue an idea that should have gone really well, but ended up crashing into a brick wall instead. “If you’re pushing in whatever you’re doing, you’re going to fail fast and way more than you succeed,” Zimmer says. Are failure and success related? “It’s that old saying, ‘You can fail without ever succeeding, but you can’t succeed without ever failing.’ The culture we live in teaches us to fear failure, and that’s a huge mistake. We try to detoxify that at First Book.” The Brick Wall Award, she says, is “a way of saying, ‘It’s OK, you did the thinking, and you gave it your best shot, and it crashed, but it was an honorable step.’”

Scott Adams, creator of the Dilbert comic strip, labored for years at jobs he hated while dabbling in creative pursuits on the side (a computer program that measured a person’s psychic powers was one of them). All of his side-ventures crashed and burned, including the earliest iteration of Dilbert. It’s unlikely he’s ever heard of the Brick Wall Award, but he embraces the concept. Of his darkest days he remembers: “I always started out with the idea that [my ventures] were long shots, and they should fail fast. Trying more things moved me from a game of low odds to a game of better odds. Failure was built into the assumption.”

Learning to Embrace Repeat Defeat

You know an idea has caught fire when higher education fans its flames. Stanford University offers a course that pushes the notion that failure – and recovery from it – are more valuable to an individual than sticking with what you already know how to do. Professor Carol Dweck teaches this freshman course called Self-Theories (200 people typically apply for 16 spots) where students are directed to tackle something “they have never had the guts to try.” Students face personal fears like singing in public or learning a new skill like dancing and then document the process, paying particular attention to the fear of failure, discomfort and doubts inherent in the experience, and how they overcame those obstacles.

So how do you truly overcome a discomfort with defeat? Ryan Babineaux, Ph.D, a lecturer at Stanford who also teaches a contrarian approach to success in his course, Fail Fast, offers five suggestions from his book, Fail Fast, Fail Often: How Losing Can Help You Win:

- Identify your fear: Find something that you would like to try but have hesitated to do because of your fear of failure. (I want to try working as a professional photographer, but I am afraid that I might not be good enough at it to be successful.)

- Reverse your thinking: Come up with a way that you can fail fast at it as quickly as possible. (I am going to find a setting where I can take lots of bad pictures and let people see them. I can try at my cousin’s wedding, which is happening next month.)

- Do it anyway: Get out there and give it a try. Make mistakes and have fun doing it. Ask others for help and feedback. (While taking pictures at the wedding, I will let people know I am a beginner and ask for comments and suggestions.)

- Fail forward: Use your exploratory actions as a means to learn from mistakes and discover what you need to know. (What parts of taking the wedding photographs were the most or least enjoyable? What pictures did people like or dislike? What came naturally, and what do I need to work on?

- Find the Next Challenge: Seek out the next opportunity to do things at the limits of your abilities. (Next time I will ask to take pictures at a wedding where I get paid for my work.)

Then Again, What If Your Boss Isn’t a Fan of Failure?

Advice to “fail fast and fail often” is all well and good, but even managers who say they tolerate failure may not be capable of implementing that mindset. (It’s a lot easier to be sanguine about failure after emerging victorious from it.) Even frequent failer Scott Adams admits that failure in the workplace can give your resume a black eye. So be smart about failure and success, by cutting your losses quickly and always having a plan B. “I’m sure there are some little pockets of departments out there where they say failure is good and they mean it,” he says. “But in general, if you fail you are in trouble. Your boss has to explain it to his boss. And even if you failed brilliantly, by the third telling, it’s just a failure. So all things being equal, success is better. Nobody is trying to fail. It’s just part of life, and you should try and fail intelligently.”

AARP asked the CEO of TubeMogul, Brett Wilson—whose progressive leadership style has been featured in The New York Times—about managers who claim to embrace failure but punish it instead. “Embracing the ‘fail-fast’ mentality is easier said than done,” he says. “Organizations must first recognize that they can only win in the long run through innovation, and achieving an innovative culture is only possible in an environment where employees aren’t afraid of taking risks that might result in failure. Organizations that get this understand that not only will they fail sometimes, but that doing so is imperative to survive over the long term.”

To encourage a failure-friendly culture, Wilson says, business-as-usual needs to be tended to while side projects—or moon shoots as he calls them—can be conducted concurrently, with no catastrophic consequences if they fail. “In this way organizations earn the right to experiment—and sometimes fail—by establishing a cadence of predictability achieving the current core business objectives.” In other words, keep one eye focused on the bottom line and the other looking toward the horizon of possibility.

For the pre-millennial generations (Boomers, that’s us) that were taught to color inside the lines, embracing a failure mindset can be a formidable task. When we talk about failure, we of course don’t suggest that failing due to procrastination, laziness, incompetence or apathy is acceptable. It’s not. We do suggest that daring and taking risks greatly carries with it the opportunity for both failure and success and that the two are not mutually exclusive. In the end, this Japanese proverb distills the failure philosophy to its essence, whether you are pursuing the next great idea or just living life: “Fall down seven times, get up eight.”

The Rise of The Failure Project

Driven by her own unexpected fear of failure as a graduate student at the University of Cincinnati, Allison Carr (who has since earned her Ph.D. in English and comparative literature) launched what she called “The Failure Project,” a public archive of ordinary people sharing stories about the fear of failure, to address the way society has stigmatized failure.

On her Failure Project website, she invites individuals and companies to post their own “failure narratives.” The idea was to debunk two myths: 1) that failure should be shameful and experienced privately; and 2) that failure only exists as the antithesis of success. “I wanted to project the message that failure is a universal experience, and that the entire range of feelings it involves—shame, sadness, anger, anxiety, etc.—are important and ok to feel,” Carr says. “Similarly, I wanted to suggest that we might benefit from understanding and experiencing failure for failure's sake, and not as a neat, predictable little opportunity for redemption or success. It's bigger than that.”

In an exclusive interview with AARP, Carr, now an assistant professor of rhetoric at Coe College in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, talks about how she conceived her unusual idea, and what we all can learn from it.

What inspired The Failure Project?

I was in graduate school at the time, beginning my Ph.D., and just having a rough go of it, feeling overwhelmed and not good enough, which were new feelings for me. I'd always found school to be pretty easy, but I started being really hard on myself, fearing I'd have to leave, and not really having a backup plan. And, you know, I had a great graduate experience surrounded by tons of creative, smart and supportive people, but not even the best grad program is one that welcomes such crises of confidence. I guess I was kind of staring into the metaphorical abyss, unable to focus on much of anything beyond this idea of failure and success—a thing I very much felt I was on the verge of—and what it meant to me personally, what it means in school environments, what it means out in the world. So I started writing about that a little bit, and along came this idea. "Hey, why don't we talk about this more?"

What was the most surprising/unanticipated thing to come out of The Failure Project?

In many ways I think I was most surprised that anyone bothered to submit their stories at all. Here I am, a total stranger, asking total strangers to send me stories about failure and success that, for the most part, expose vulnerabilities and insecurities, and then I'm going to put those on the Web. That response told me that I was onto something, propelling me into further research and, down the line, becoming the subject of my dissertation, which looked primarily at the emotions of failure and how those impact learning environments.

Are fear of failure and aversion to risk the same thing?

Generally I would say no, I don't think these are really the same, though I think they are closely related. I think a fear of failure can cause an aversion to risk-taking, certainly, and that generally fostering an aversion to taking risks can result in a more pronounced fear of failure, but I think these things are not totally congruent. For example, I would say that despite my enthusiasm for failure, when it comes to my work and the things I care about most deeply, I am petrified of failing, and I think most people would nod their heads and say they feel this way too.

But I also know that big risks often reap big rewards, so I'm frequently talking myself into those scary situations. My willingness for taking risks doesn't mitigate the fear. Things don't always work out the way I'd like—sometimes, it's just a total failure—but I think that's OK.

Were there any recurring failure themes you've identified in the stories that have been posted on The Failure Project?

Sure, I think probably the one thing that appears in all of the submissions is a feeling of loneliness. Fear of failure makes people feel really isolated, at a time when we probably need people most. I think it probably causes us to withdraw. So I'd hoped the archive would help in that regard as well, giving people some sense of community, even if they're moping around in their jammies alone.

You will be teaching a course in failure this fall at Coe College in Cedar Rapids. Tell us briefly about that and why failure courses seem to be becoming a trend in higher education.

We'll be reading a mixed bag of essays and articles tackling the “stuff” of failure from a wide variety of viewpoints, but what I'm most excited about is asking students to undertake a failure project of their very own. They'll have to identify some kind of activity or task at which they are sure to fail, and attempt to master it, all the while documenting the experience and striving to learn from mistakes and each other as learners and, well, as failures! We're really going to try to own that word.

As for the national trend … I think [for] young people moving toward independence from their parents, and older/middle-aged people moving toward retirement … there's a lot of uncertainty in these big transitions, and much hangs in the balance between taking risks and protecting oneself. So it makes sense that we would want to explore these ideas in classrooms, where we ostensibly accumulate the skills and tools needed to really thrive out in the world.

Have you applied any of the failure lessons learned through The Failure Project to your own life?

Maybe this sounds quaint, but it's true—I'd say The Failure Project has helped me remember that nobody is better at failing than anyone else; nobody has it all together all the time. Failure is everywhere, and it always sucks. But, it enables a change of perspective, and that's why it matters. Learning from mistakes are lessons I think we learn again and again, maybe proof of their importance. I'm someone who has been accused of liking to fail, which is mostly true, and it still wrecks me. But it's OK to feel wrecked. Maybe that should be the archive's motto.

What's the one thing people can do right now to change their mindset around failure?

Fail early, fail often! Practice failing any chance you get. I don't want to suggest that there is any one right way to fail or to feel about failure—only you can know what that is for yourself, and you'll only come up with that if you’re taking risks and you give yourself the chance to fail. Take that chance. But, you know, listen to your financial advisers too.