AARP Hearing Center

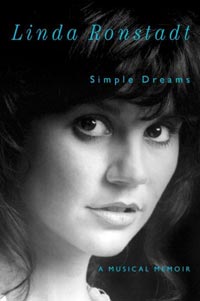

From her first burst of success in the 1960s as the lead singer for L.A.’s Stone Poneys, Linda Ronstadt has been as famous for fiercely guarding her private life as she has for the robust and glorious soprano that made her one of the supreme song interpreters of her generation.

Yet in an interview with AARP in advance of her coming memoir, Simple Dreams (Simon & Schuster, Sept. 17), Ronstadt opens up about the life-altering news she did not put in the book — she has Parkinson’s disease — and its tragic side effect: “I can’t sing a note.”

Though her book mentions that her voice began to change at age 50, Ronstadt, now 67, had never offered a solid explanation for her 2009 retirement (the book does cryptically mention a time when she had a “still-healthy voice”).

The winner of 11 Grammys during a 40-year career that produced more than 30 albums, Ronstadt recorded her final CD (Adieu, False Heart, with Cajun musician Ann Savoy) in 2006. Three years later — on Nov. 7, 2009 — she gave what she calls her last concert at the Brady Memorial Auditorium in San Antonio.

After that, Ronstadt simply declined all invitations to do more.

In late 2012, when a friend asked her to sing on a tribute album to Jackson Browne, a close friend from her L.A. days, she wrote in an email: “I have a serious case of being 66 years old and am completely retired from singing. Of course, one is always pleased to be asked, so tell them I said thank you.”

What old friends and fans did not know is that for the past seven or eight years, Ronstadt had suffered from symptoms that suggested Parkinson’s disease. Eight months ago, a medical diagnosis confirmed it. Never one to shy from a challenge, Ronstadt faces her disease with the determination to push for more and better treatments, both for herself and for other Parkinson’s patients. (For more about Parkinson's disease, see the box on page 4.)

In the exchange that follows, Ronstadt assesses her career and explains how her Parkinson’s was detected.

Q: You wrote your “musical memoir,” Simple Dreams, entirely yourself. Was that difficult for you?

A: Well, I’d never written anything longer than a thank-you note before. I never kept a diary or a journal. But I’m a reader, and I can put a coherent sentence together, so I thought I could make it honest and clear.

Q: You talk in the book about your love for animals and your pet, Luna the cow.

A: Oh, Luna! Yeah, I loved her — she was such a nice old girl — but I got a tick from her, and that’s probably why I’m sick.

Q: You mean you have a tick disease now?

A: Well, I had two very bad tick bites in the ’80s, and my health has never recovered since then.

Q: Is that why we don’t see so much of you?

A: I can’t sing. I have Parkinson’s disease, which may be a result of that tick bite. They’re saying now they think there’s a relationship between tick bites and Parkinson’s disease — that a virus can switch on a gene, or cause neurodegeneration. So I can’t sing at all.

In fact I couldn’t sing for the last five or six years I appeared on stage, but I kept trying. I kept thinking, “What if I tried singing upside down? Or standing on my head? Or while juggling? [Laughs] Maybe I’d be able to sing better then.”

So I didn’t know why I couldn’t sing — all I knew was that it was muscular, or mechanical. Then, when I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s, I was finally given the reason. I now understand that no one can sing with Parkinson’s disease. No matter how hard you try. And in my case, I can’t sing a note.

.jpg?crop=true&anchor=13,195&q=80&color=ffffffff&u=lywnjt&w=2008&h=1154)

More on entertainment

Michael J. Fox Is Feelin' Alright. Oh, Yeah

More than two decades after being diagnosed with Parkinson's, he gets by — even thrives.