AARP Hearing Center

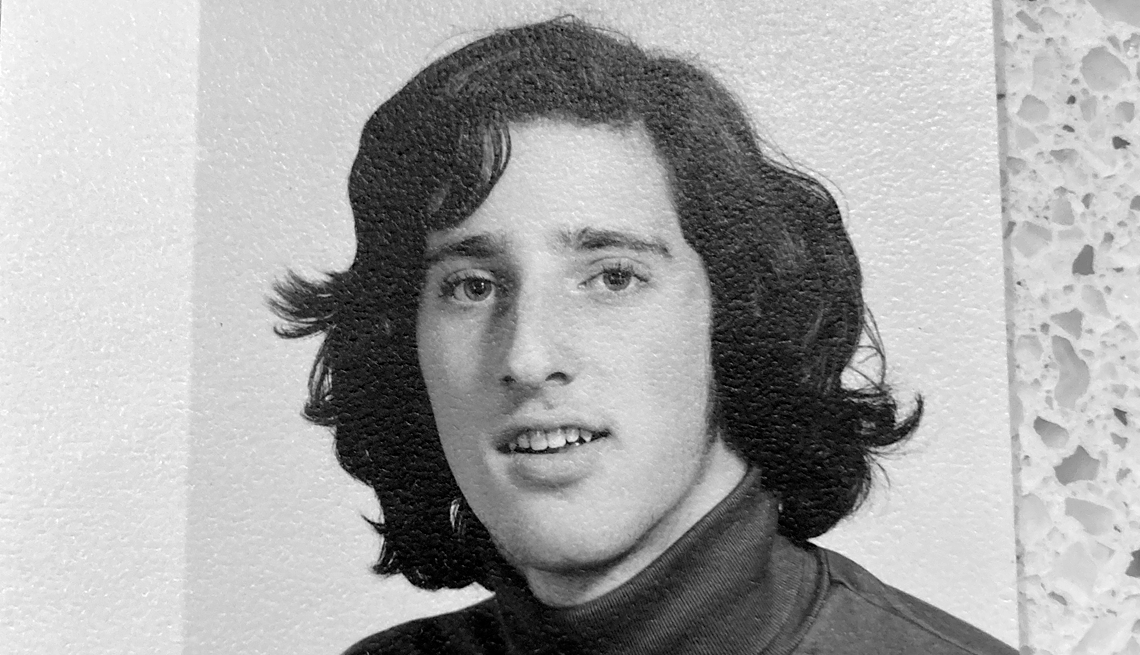

Long-term grief isn’t continuous; it peaks suddenly, triggered by images and events. I recently relearned this lesson during my first visit to my father’s hometown of Hoboken, New Jersey, a mile-square town directly across the Hudson River from the skyscrapers of Manhattan. Fifty years had elapsed since his death from brain cancer when he was 52 and I was 15, yet I approached the trip without many expectations or feelings. In my mind, my wife and I were simply accompanying our son and daughter-in-law on their apartment hunt there. For fun, I’d brought along some black-and-white photographs of the town from the 1920s and 1930s handed down to me by my father’s mother.

As we walked along Washington Street, the town’s main thoroughfare, we paused at the 1880 four-story brownstone where one of the faded photos showed my father as a toddler, dressed in an oversize nightshirt, looking up at the camera from playing in the small, fenced-in backyard of his family's ground floor apartment. A block away was the storefront of a nail salon looking nearly identical to the 100-year-old snapshot of the Paradise Hat Shop, which my grandmother ran at that site. At first, it felt uncanny that so much tangible evidence of my father’s childhood could still be seen. Then, for the first time in several months, I was flooded by a wave of sadness about his early death.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Most people who have lost close family members feel grief immediately after the death, but months or a year or two later, it is no longer the constant state of their lives. Instead, they experience sharp pangs of sadness only at certain times of the year, such as the deceased’s birthday or death anniversary, or even during family celebrations, such as weddings and graduations when the person’s presence is sorely missed.

For caregivers who have lost their care receivers, those feelings tend to come more often. Even if they thought the care receiver’s death at the time was a blessing and a relief, there is something about the intensity of caregiving that makes for an enduring emotional attachment. For many of us, the images of our relatives’ suffering toward the end are burned into our brains and crash our thoughts at inopportune times. For some, the strong feelings of responsibility we had as caregivers spawn guilt afterward.

You Might Also Like

How Caregiving Can Alter Dreams and Goals

Post-caregiving life may be different than you imagined — in a good way25 Ways to Find a Greater Sense of Purpose

Use our topical advice to elevate your curiosity, plan your third act and expand your horizons

Gladness Gurus Share Top Tips for Finding Happiness

These strategies can make every day more fun, festive and fulfilling

AARP Members Only Access

Enjoy special content just for AARP members, including full-length films and books, AARP Smart Guides, celebrity Q&As, quizzes, tutorials and classesRecommended for You