AARP Hearing Center

5

“Have you ever eaten a slice of the blackbird pie at the café?”

“Yes, indeedy,” Mr. Lazenby said. “Every day for thirteen years, give or take a day here and there when the restaurant was closed up. Quite tasty, the pie.”

“The pie isn’t really made of blackbirds …?”

“No, sir. It’s regular pie.” His old eyes twinkled. “Usually fruit.”

“No other specific ingredients?”

“It’s a Callow family secret recipe. If you’re needing the ingredients, you’re plumb out of luck.”

The reporter thumbed a drop of condensation from his mason jar. “Do you believe the local legend that the pies will make you dream messages from dead loved ones?” He scoffed. “That blackbirds actually sing those messages—notes, as the writing on the soffit indicates— into the pies?”

Mr. Lazenby stood up, straightened his bow tie, and set his hat firmly on his head, pulling down the brim. “You haven’t had a piece of pie yet, have you, sonny boy?”

“No. Why?”

“If you had, you’d know the answer to your own question and wouldn’t be wasting my time. We’re done here.”

Anna Kate

“That bird must have gone out the same way it came in,” I said, coming down the stairs into the kitchen. It was the third time I’d done a search. “There’s no sign of it anywhere.”

“Probably so,” Bow said as he lifted a chair onto a table in the dining room. “Birds are such curious creatures.”

Jena slid a mop across the kitchen floor. “The saying is that curiosity killed the cat, not the bird.”

What looked like pain flashed in Bow’s eyes, darkening the murky blue to almost black. His salt-and-pepper beard was cut short and neatly trimmed, but he repeatedly dragged a hand down the side of his face toward his chin as though smoothing stray hairs. “Sometimes it almost does both, doesn’t it?”

“Sure enough,” she said with a wan smile.

As I grabbed a rag and a bottle of cleanser, I glanced between the two of them, wondering about the strange tension in the air. It was almost like they were sharing a memory, one tainted with sadness. “Do you two have pets?”

We’d already tackled the prep for tomorrow and were finishing up the kitchen chores. As soon as we were done, I wanted to track down Summer Pavegeau. I owed her a piece of pie, and it was a debt I didn’t want hanging over my head. I knew what the pie meant to her.

Whether that pie would bring Summer any comfort tonight when she dreamed, I wasn’t sure. I hoped so, but I just didn’t know, what with Jena having baked the pies. Tonight I’d take over the task.

“Not unless you count the fake coyote in our vegetable garden,” Jena said with a smile. “Keeps away some of the dumber critters.”

“Where do you live? Is it close by?”

“Not far,” Bow said. “A couple of blocks away.”

“It’s a small two-bedroom cottage near the bridge over Willow Creek,” Jena said. “It’s not much to look at, but the land is beautiful and the burble of the creek at night is like a lullaby.”

Her voice had softened to the point that it felt like a lullaby. “Sounds peaceful.”

“Most times, it is.” Jena reached up on top of a shelf for a roll of paper towels and let out a soft groan, dropping her arm back down.

“Are you okay?” I asked.

“Fine, fine,” she insisted. “Just an old injury that never healed quite right. Sometimes I forget, is all.” She reached up with her left arm and grabbed the paper towels.

“Maybe you should see a doctor. It’s possible something can still be done ”

“Said just like the wonderful doctor you’re gonna be someday. But I’m fine, sugar. I learned to live with this little foible of mine a long time ago.” She massaged her right shoulder. “I’m sure the Lindens are real proud that you’re going to follow in your daddy’s footsteps, to continue the Linden legacy.”

“Jena,” Bow sighed.

“What?” she said, tearing off a paper towel. She wiped a spill on the side of a cabinet. “Everyone knows AJ Linden was going to be a doctor like his daddy and granddaddy. By the way, how did your time with Doc go today, Anna Kate? I haven’t had the chance to ask.”

My mother had strongly encouraged me down the same path as my father. It made sense. Healing was in my blood, after all, and following his lead made me feel connected to him in a way nothing else did. I wanted him to be proud of me. But I didn’t want to think about what the Lindens, Doc and Seelie, thought of my career choice. I certainly didn’t want to care.

I rubbed at a spot on the counter with a rag. “Doc invited me to Sunday supper. I said no. I had to say no.”

“You don’t think you made the right decision?” Jena asked in that gentle trill of hers, obviously picking up on my conflict.

I added more cleaner to the counter, and a lemon and lavender scent filled the air. “Were you guys around when the accident happened?”

Bow dropped a chair, and the crack when it hit the floor sounded like a gunshot. “Butterfingers,” he said. “Sorry. The chair’s fine.”

Jena pushed the mop back and forth. “We’d arrived in town shortly before the accident,” she said. “Why do you ask?”

“My mother was always a little dodgy when talking about the accident and its aftermath—probably trying to spare my feelings. But I want to know what truly happened.”

“Well, I can fill in some of it,” Jena said, making her way toward me with the mop.

“Jena,” Bow warned.

“Hush up,” she said. “Anna Kate has the right to know.”

“Know what?” I asked.

Bow sighed and picked up another chair.

Jena’s dark eyes were full of light when she said, “To hear tell, Eden and AJ had been fighting like cats and dogs that summer, with him heading off to school down at Alabama. Eden didn’t want to be left behind. She was itching to leave Wicklow, and she always thought she’d be leaving with AJ. But they couldn’t figure out how to make it all work, between school and expenses and Zee wanting Eden to stay here—they’d been at each other’s throats too, over Eden wanting to leave.”

I’d known that last part, because that tension between them had never fully ebbed.

“Finally,” Jena said, “Zee relented for the sake of Eden’s happiness, and even offered up a small loan to help get the lovebirds on their feet. A plan came together. Eden and AJ would rent an apartment in Tuscaloosa. After getting settled, Eden would find work, eventually enroll in a nursing program, and start planning a wedding. And after their schooling, they’d go wherever their whims took them, see the world together before the winds of destiny brought them back to Wicklow.”

“Back to Wicklow?” I asked, eager to hear more. To hear it all. “Why?”

“You see, AJ was destined to take over his daddy’s practice. And your mama, well, her destiny is here, with the blackbirds. It was why Zee was willing to let Eden go and fly free for a while. She knew Eden would come back. That she had to come back or her soul would never be at peace.”

I glanced out the back windows, toward the mulberry trees.

No matter how far a guardian roams, she will always return, and while away she will never be settled, as her soul is tethered to the roots of the trees. She’ll never be truly content until she’s home among the roots, comforting and healing once again.

Jena leaned on the mop. “But Eden and AJ’s plans were derailed before they could even rent an apartment.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Seelie.”

Why was I not the least bit surprised?

“When Seelie caught wind of the plans, she threatened AJ, saying she wasn’t going to let him play house on her dime. She wanted him to join a fraternity and not tie himself down to Eden so young. Seelie gave him an ultimatum. College or Eden.”

I couldn’t imagine the pressure he’d been under, having to make a choice like that. Forced to pick between his dream of becoming a doctor—and the family expectations that goal carried with it—and the woman he loved.

Jena dunked the mop in a bucket. “AJ and Eden were on their way back from a tour of the Alabama campus when the crash happened. Seelie believes AJ told Eden he’d chosen college over her and that Eden, in a fit of madness, drove off the road.”

“Seelie’s the only one who believes that,” Bow added quickly as he set another chair on a table.

It was the first time I’d heard any of this, and I ached with the knowledge, feeling a depth of sadness for my parents. “Do we …” I took a breath. “Do we know for sure that had been his decision?”

“No, ma’am,” Bow said. “Not since Eden couldn’t remember anything from that day. Thankfully, the police declared the crash an accident, but Seelie still insists to this day that it happened her way.”

I forgave the “ma’am” in this situation. “But the police cleared my mom. Why can’t Seelie let it go?”

Jena said, “Technically, the police didn’t have enough evidence to charge Eden. And while Seelie’s voice carries a lot of weight in this town, a good portion of the community backed Eden. Everyone with eyes saw how much she and AJ loved each other. As soon as it was announced that no charges were going to be filed, Eden left town. Many expected she’d be back one day, destiny being what it is, but then, they didn’t know about you. It’s clear now why she stayed away.”

Absently, I nodded. “I think I might stop by the library after I go to the Pavegeaus’ … It’s inside the courthouse, right?”

“Yep. Second floor. Are you going to look at old newspapers?” Jena asked, eyebrow raised.

I smiled at how well she could read me. “Guilty.” I wanted— needed—to know anything and everything about that accident. Old articles were a good place to start.

“Best you hurry, then,” Jena said. “The library closes at five. We’ve got the rest of the chores covered.”

“Are you sure?” I asked.

“Positive,” she said.

I tossed the rag in the laundry room and put away the cleaner. “I don’t know how you two do this day in and day out. All this work is exhausting.”

Bow said, “For one, it’s not usually this busy.”

“For another,” Jena added, “Zee always hired day help when we needed it most. It’s something for you to consider.”

“I’ll think about it.” Hiring someone right now seemed a daunting challenge. I’d wait a few days, see if the birders stuck around, before putting a sign in the window.

Bow finished with the chairs. “You’ve got that map I drew to the Pavegeau place?”

“I do.” I pulled it from my back pocket and stared at the squiggles, trying to pretend they made sense.

“You sure you don’t want me to show you the way? It can be tricky,” he said, offering for the third time.

“I’m sure. Thanks. I need to start finding my way around here on my own.”

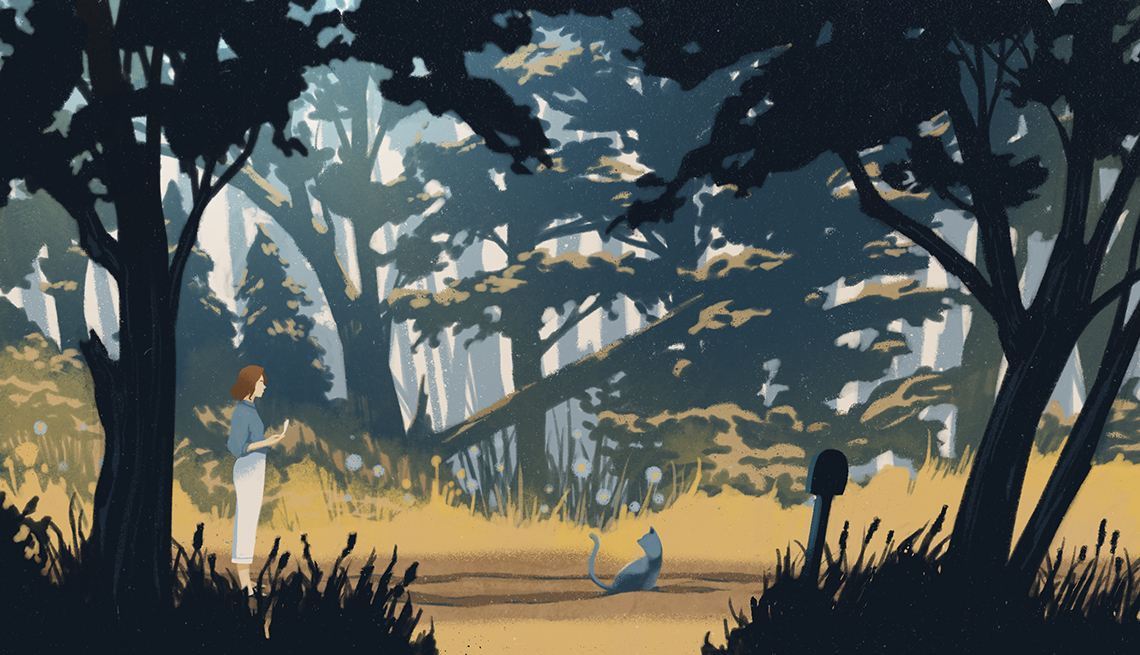

Jena leaned the mop against the pie case. “The Pavegeau place isn’t exactly on the beaten path, tucked off in the woods like it is.”

“I’ll be okay. And this is a great map,” I lied as I headed for the front door. “I’ll find my way, no problem.”

Jena said, “Be sure to announce yourself loud and clear when you get there, so you don’t get your head shot clear off.”

I looked back at her to see if she was joking.

She wasn’t.

“People ’round here are real protective of their land.” Her dark eyes were wide with reverence. “And Aubin hasn’t been quite right in the head since his accident. He used to be real social, but he’s become a bit of a loner, practically going off-grid. I can’t imagine he’s too keen on drop-in visitors, especially strangers.”

“Aubin? Accident?” I asked.

“Summer’s father,” Bow said. “The family was in a bad wreck six winters ago. Hit an icy patch and slid down the mountain. Not a scratch on Summer, but her mother, Francie, died from her injuries. Aubin was banged up pretty badly. Head and internal injuries. Mangled leg.”

“How horrible.” I quashed my own grief for the father I’d never known, which tended to pop up at any mention of fatal car accidents, and glanced at the pie box in my hand. I was more determined than ever to get it to Summer.

“Terrible time.” Jena tsked.

“Is Aubin okay now?”

“Mostly,” Jena said. “But no denying he’s a changed man. Quiet when he used to be the life of the party. Cautious when he used to throw caution to the wind. He doesn’t come into town much except to visit his wife’s grave. He’s at the cemetery every day come four o’clock, rain or shine.”

“Does he work?” I asked, thinking of Summer selling me eggs this morning.

“Used to.” Bow pulled a trash bag out of its can. With a flick of his wrist, he tied off the bag and set it aside. “He was a mail carrier. Went on disability for a while after the accident, then was reassigned to a clerk position since he had trouble driving with his bad leg and all. But he up and quit after a month or so.”

Jena tapped her temple. “Mentally he hadn’t been ready to go back to work. Nowadays, he makes do with what he and Summer grow on their land and by selling handmade soaps and the like at craft fairs. They get by okay.”

Bow put a new bag in the trash can. “It’ll take me but a minute to finish up here. Let me go with you, Anna Kate. I can make introductions.”

“No, no,” I insisted stubbornly. I didn’t know why Summer had hightailed it out of here earlier, and I didn’t want to spring more people on her than I had to. “I’m used to figuring out things on my own. I’ll be all right.”

“But sugar,” Jena trilled. “You have us now to help you out.”

“Thanks all the same. You two have done so much for me already,” I said, trying to reassure them. “Speaking of, thanks for everything today. I couldn’t have reopened the café without your help.” I pulled open the front door.

“You’re welcome, you sweet thing,” Jena said. “Please don’t get shot dead. I’ve become mighty fond of you.”

“I’ll do my best.” I gave them a wave and let the door close behind me. I’d made it two steps before looking at the map and realizing I was heading the wrong way. I turned around, glanced into the café, saw Bow shaking his head, and waved again.

I’d barely taken two more steps when Sir Bird Nerd stepped in front of me.

“Sorry to bother you, ma’am,” he said. “I just wanted to say thank you for sending out the cold water and tea sandwiches earlier. Very kind of you. Most of us hadn’t planned to stay here the whole day long.” He held his hand out. “Zachariah Boyd.”

I shook. “Anna Kate Callow. You’re welcome, and I thought we discussed the ma’am thing.” I’d rather share the food than see it go to waste, and as the day had gone on, the birders seemed to wilt in the heat. I didn’t want any of them passing out in the side yard.

His cheeks colored. “Right. Sorry about that.”

“Now if you’ll excuse me, I have to go—” I eyed the map, looking for landmarks I recognized.

“Before you do …” he said.

“Yes?”

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members