AARP Hearing Center

Seventeen

Zoe

SHE HAD NOT planned to look for the American but, day after day, there he was in the middle of biology or Latin or running; his face appeared when she was brushing her hair, or peeling potatoes. She heard again the odd lilt of his voice: More trouble than you ever dreamed of. She asked Duncan about the painting he’d reminded her of—some saint in a rocky landscape—and Duncan pulled out one of his art books and opened it to a pale-faced Christ, wearing blue and purple robes, mountains writhing in the background. She carried the book back to her room, and that made things worse. There were the high cheekbones, the shapely mouth, the brown hair, though much longer. She remembered her mother saying, “You have the right to change your mind. Right up until the last moment. Beyond. Don’t let embarrassment, or fear, stop you if you want to say no.” But I want to say yes, she thought. That was the conundrum: how to say yes.

So on Sunday when her mother said she was meeting a friend in Oxford, she ran to change her sweater. As they headed out of town, past the church and the primary school, her mother talked about one of her clients. While burning his wife’s underwear in the garden, he had accidentally set fire to a hundred-year-old holly tree.

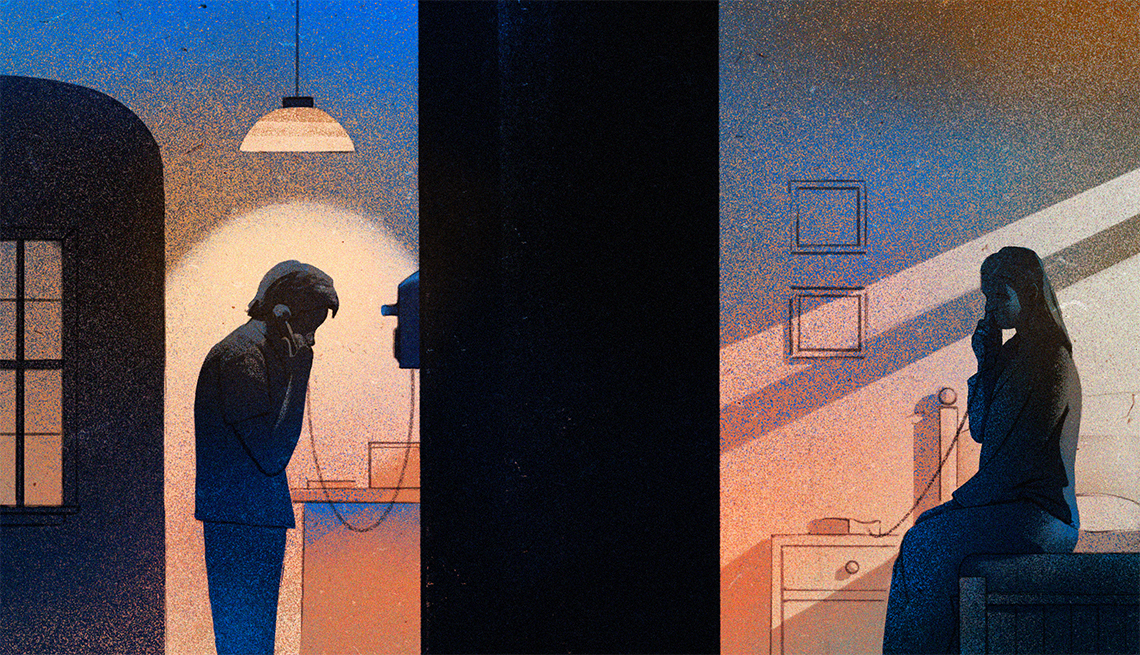

“The more I listen to him rant,” her mother said, “and read his wife’s depositions, the more I realize I’ll never know what went on between them. She claims ten years of bliss before he started to work late every night. He claims it was a mistake from day two. I keep thinking they could still be happy if they could let go of their anger, but it’s as if they’re on two trains speeding in opposite directions. Neither of them can get off.”

Was her mother suggesting that feelings were optional? That one could pick and choose between, say, love and hate, boredom and pleasure? As they swerved to avoid the postman’s red van, parked half on the verge, no house in sight, Zoe set aside the idea to examine later. “Did you have boyfriends before Dad?” she said.

At once she worried she had come too close to what she longed and dreaded to ask, but her mother, sounding pleased, was already saying, “Several.” She described her sixth-form boyfriend, Kevin, who was brainy and funny, then a couple of boys at university. “I kept looking for someone with whom I could share everything: work, ideas, travel, books, music. When I first met Hal, he seemed too different—a blacksmith who’d been running his own business since he was sixteen.”

“You and Dad share lots of things.” She heard herself pleading.

“We do.”

Was that all she was going to say? Zoe did not dare to press her. But a mile later, as they circled a roundabout, her mother continued, “And our differences are mostly for the good. I’m always preparing for disaster. Hal reminds me there are silver linings. How was the Latin test?”

In the car park she leaned over to kiss Zoe. “If you want a lift home, be here at five.”

They headed in opposite directions. She doesn’t know, Zoe thought, with a gust of relief. But almost immediately, as she turned into the street, relief turned to dismay. What did it mean that her father was lying every minute, and that her mother had no idea? Perhaps even now he was meeting the woman. And what was she, Zoe, doing walking the crowded streets on a raw November day, stupidly hoping to find one person, a man whose name she didn’t even know, among so many? The pavement echoed under her new boots, the people she passed looked chilled, cramped, in their tiny lives, the blood inching through their veins. Litter rattled across the pavement; a beer can rolled in the gutter.

“Fifty pence for a cup of tea, love?”

A woman, seated on the steps of a bank, was holding out a paper cup. Her turquoise tracksuit, only a little ragged at the collar and cuffs, made her eyes look very blue. Zoe’s hand closed around a fifty-pence piece. Before she could change her mind, she dropped the coin in the cup.

“God bless,” said the woman.

Two minutes later there he was, coming out of a bookshop. It was incredible, and it was true. He was on the far side of High Street, walking with another man, deep in conversation. He wore the same leather jacket. His hands, accompanying his words, made neat, precise gestures. She darted across the street and fell in behind him and his companion.

“But the northern Catholics ... ,” the other man said.

They were, she guessed, heading for the station. At the idea of him boarding a train, she panicked. When there was a gap in the traffic, she repeated her trick of their first meeting: crossing the road, running ahead, and crossing back. As the distance dwindled, her pace slowed. Suppose, in the midst of conversation, he failed to notice her? Or, even worse, failed to recognize her? What had seemed impossible—he’d forgotten their meeting—was both possible and probable. Closer, closer, and still he was engrossed in conversation, his face turned toward his friend. Look at me, she cried silently.

He was almost at arm’s length when his eyes, at last, met hers. “Hello,” she said, stopping midstride.

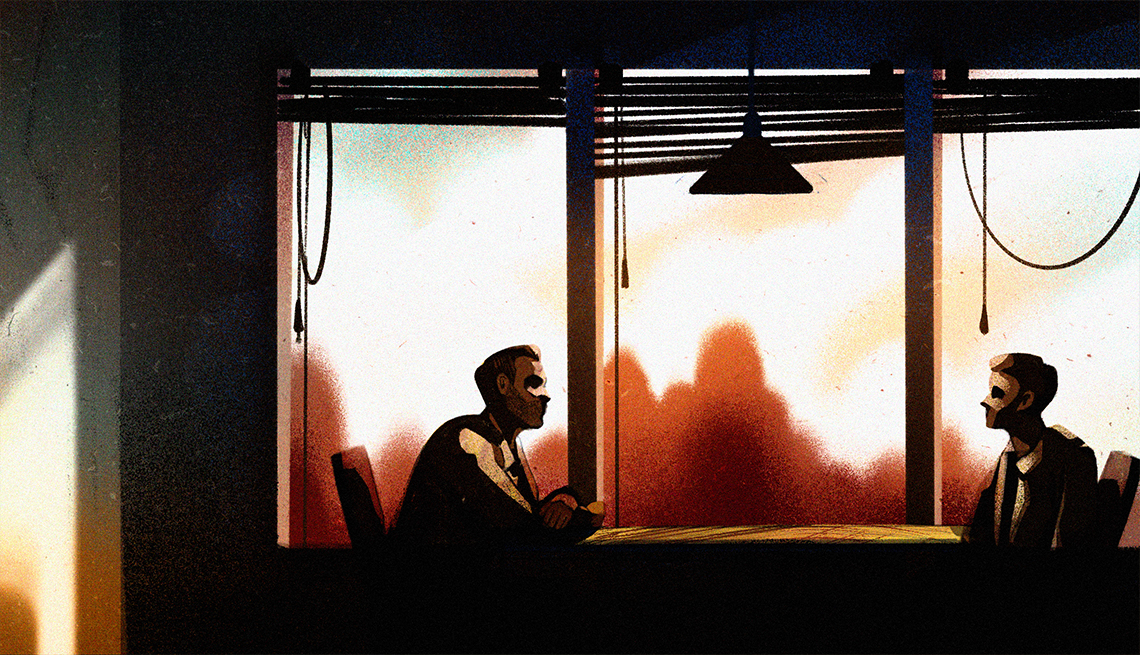

“Hi.” He stopped too. Pedestrians swerved around them on the narrow pavement. “This is my friend, Jerome.”

Turning to Jerome, she said brightly, “I’m Zoe.”

“Good to meet you.” Jerome too was American, indeed more American: his skin tanned, his teeth very white and regular. “Sorry, I’ve got a train to catch.”

She fell in beside them. Jerome was holding forth about Shakespeare, whom, he claimed, had become a secret Catholic during the years he’d spent in Lancashire. “It’s in the plays,” he said, “if you know where to look. One of these days, I bet they’ll find proof.”

“You could get Ladbrokes to offer you odds,” Zoe suggested.

Jerome smiled. “That’s one of your betting shops, isn’t it? Three to one I’m right. Excuse me, I’m going to jog the rest of the way.” He hugged the man, threw another nice-to-meet-you at Zoe, and darted into the traffic with surprising agility. They stood watching as he zigzagged across the road, one hand raised in supplication to oncoming cars.

“Well.” The American turned to her, shifting his backpack to the other shoulder. “What’s your name?”

“Rufus. As you can see, I didn’t take your advice and go home.”

What could she say? But he remembered; their meeting had left its mark. She sensed him wrestling with something, another commitment perhaps, and then deciding.

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members