AARP Hearing Center

Nineteen

Zoe

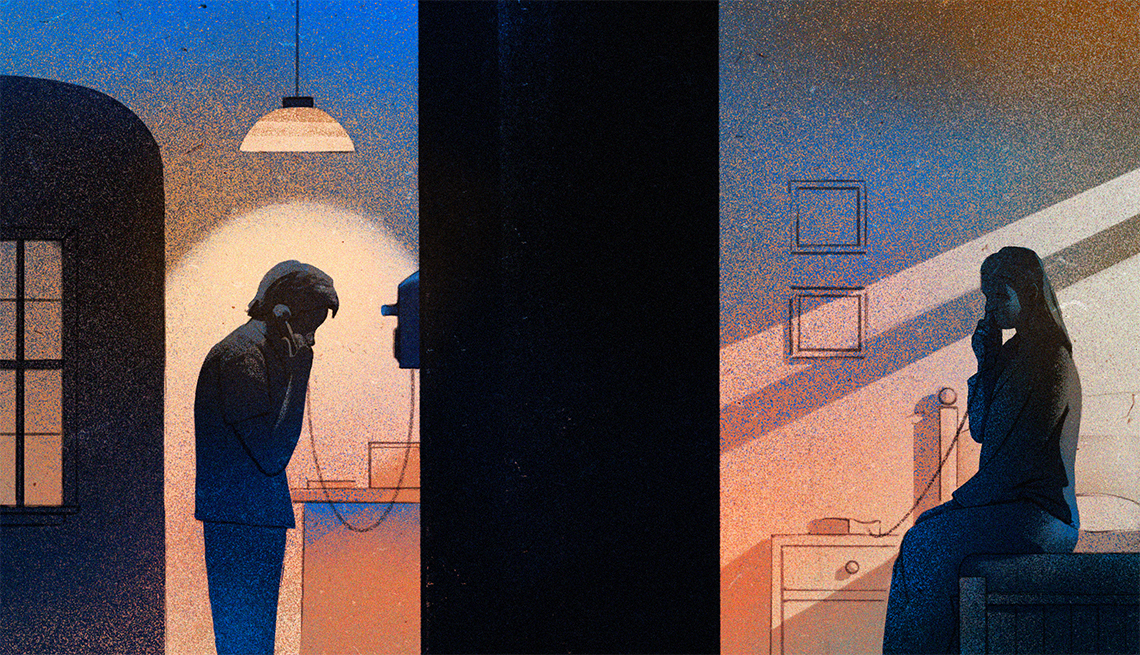

WHEN SHE GOT home from the butcher’s, her mother was circling the ficus with a watering can. Without looking up, she reached for a yellow leaf and said, “Can you take Duncan swimming?”

“Why can’t Dad take him? I’m going round to Moira’s.”

At once she was dismayed—the last thing she wanted was to draw attention to her father’s activities—but her mother, moving on to the ferns, said he was driving the fencing team to a competition. “I really need to do my Greek homework,” she added.

“It would be a big help, darling.”

In her relief, Zoe said she would devote her afternoon to unpaid child care. Already she was looking forward to spending time with Duncan; perhaps she could tell him about Rufus. They gathered towels and costumes and emergency Kit-Kats. She brought her hair dryer in case the one at the pool was broken. Duncan stopped to say goodbye to Lily.

“Come on,” she said. “We’re going to miss the bus.”

They ran down the rainy street, backpacks thudding. She let Duncan set the pace until the last corner when, at the sight of the bus, lights glowing, she sprinted ahead. “My brother’s just coming,” she told the driver. As soon as he scrambled up the steps, the bus jerked forward. Duncan was smiling, and she could feel herself smiling too. If they’d left five minutes earlier, she thought, they’d have made it easily, but they wouldn’t be so pleased. As she slid into an empty seat, she saw Ant ride by on his scooter. “There’s Ant,” she said.

“Do you miss him?” Duncan sat beside her.

“I miss his scooter.”

“Now you have a job, you could save up to buy one.”

“I’m only working six hours a week. Besides, Mum would have kittens.” On her right shoulder she felt the chill of the window, on her left the warmth of Duncan.

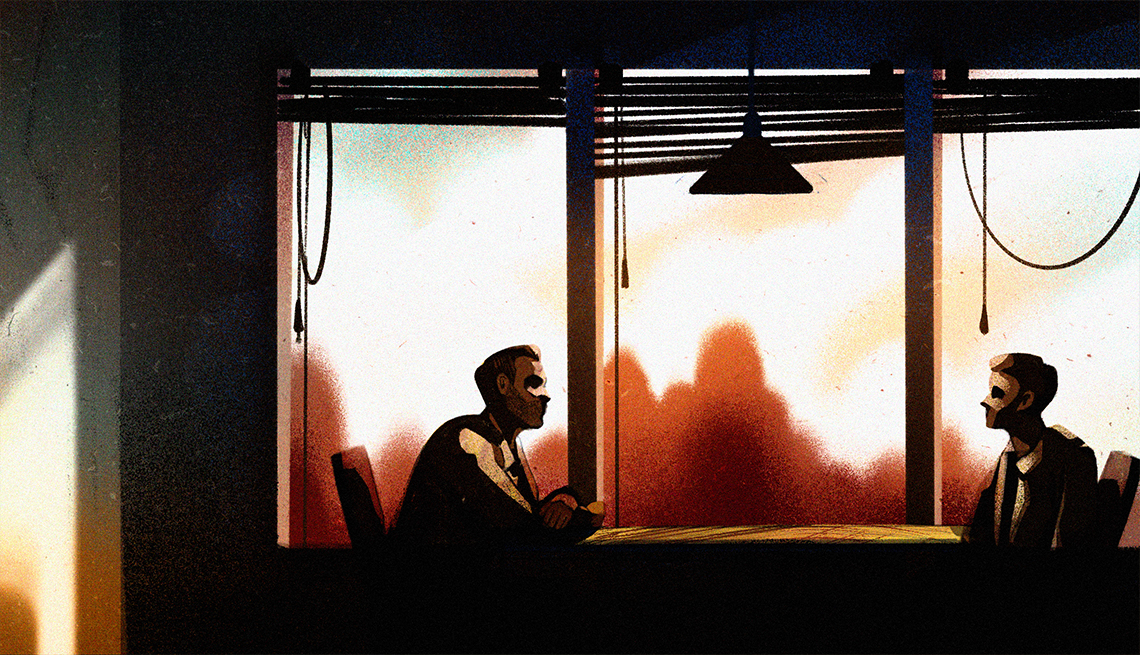

“Do you ever wonder about my parents?” he said.

Did he somehow know about their father? Then, with a jolt, she heard the “my.” He was asking not about Hal and Betsy but about those shadowy people whose DNA he shared. “No,” she said.

“I’ve been wondering about them.”

The bus thudded over the first of the speed bumps outside the primary school. “But you’ve never met them,” she said. “They could be on this bus, and you wouldn’t know.”

He stood up to scan the other passengers. One or two people looked back, their attention caught by his serious gaze. He sat down again. “I don’t think so. Put your hand on your knee.”

She put the hand nearest him, her left, on her thigh, palm down. Duncan did the same. She saw her skin, that color called white, which in her case was some mixture of pink and beige, and her fingers, each a different length, the red tooth mark Leo had made, her nails a little ragged. Duncan’s skin was closer to the color of tea without milk. His fingers were longer and thinner; there was a smear of blue paint on his index finger; his thumb was a different shape.

“So?” he prompted.

“Your birth mother was Turkish. She was living in London when she had you. That’s all I know.”

“What do you see when you look at your hand?”

“I wish I had longer fingers and could grow my nails.”

“Your hands are the same as Mum’s. Dad’s and Matthew’s hands are more like Granny’s.”

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members