AARP Hearing Center

Twenty-three

Matthew

BEFORE HE COULD protest—he was doing his homework—Zoe had crossed the room and was standing beside his desk. “I have to tell you something,” she said. “You can’t tell anyone, not Duncan, not Rachel. Not even Benjamin.”

First Duncan, now her. “Benjamin won’t tell if I tell him not to,” he said, just to be annoying.

“Promise.”

Sometimes, with her cynical remarks about Ant, her sharp insights into their teachers, Zoe seemed older, but the way she said “Promise,” as if a single word could keep them safe, made her seem much younger. He put his hand on his French dictionary. “I promise I won’t tell anyone. Not even Rachel, not even Benjamin.”

“Dad’s having an affair.”

More than any evidence she might offer, his own immediate acceptance signaled the truth. What else made sense of their father so often being late, forgetting and muddling arrangements, of the way he had started seeing old friends and cooking new recipes with ginger and coriander?

Zoe was still watching, waiting for the effect of her words. “Aren’t you surprised?”

“Yes, but not really. How did you find out?”

“I saw him leaving a café with a woman, and then there was a photograph of her on the beach in Wales. Remember the weekend he went to the cottage without us?”

He was nodding, rearranging the past. “And that day he was late to pick us up, the day we found the boy—maybe he was seeing her?”

They shared the satisfaction of solving a small mystery. Then Zoe, eyebrows arching, said, “Do you think we ought to do something?”

“Like what? Talk to him? Tell Mum?” He was throwing out suggestions, waiting to hear how they sounded.

“No!” she exclaimed. “He’d be furious if we said anything. We don’t want him to feel he has to choose. As for Mum, I can’t imagine what she’d do—drive the car into a ditch? Have a breakdown? I like living here, having two parents. You’ll be off at university soon, but Duncan and I are stuck.”

“You can always come and see me in London.” Briefly, thinking of being at university, he felt better. Then the import of what she’d told him hit him. His father had put their family at the mercy of this woman; she could send an anonymous letter, or phone, or knock at their door, and everything would be over. “What do you think she wants?” he said.

Zoe fidgeted with her shirt cuffs. “She must know Dad’s married, that we exist. Perhaps it’s enough, their occasional dates. She looked like a nice person. She wasn’t much younger than Mum, or tarty.”

He had a sudden flash of himself and Rachel beneath her billowy duvet.

“When we found Karel,” Zoe went on, “I kept thinking if I did, or said, the right thing, he’d wake up. Now I feel as if I’m waiting for someone, or something, to wake me up, but I don’t want it to be Mum and Dad having a catastrophic row.”

Alone again, studying the sentence he had begun—Mon ami Benjamin n’aime pas—Matthew thought, My family is in disarray.

***

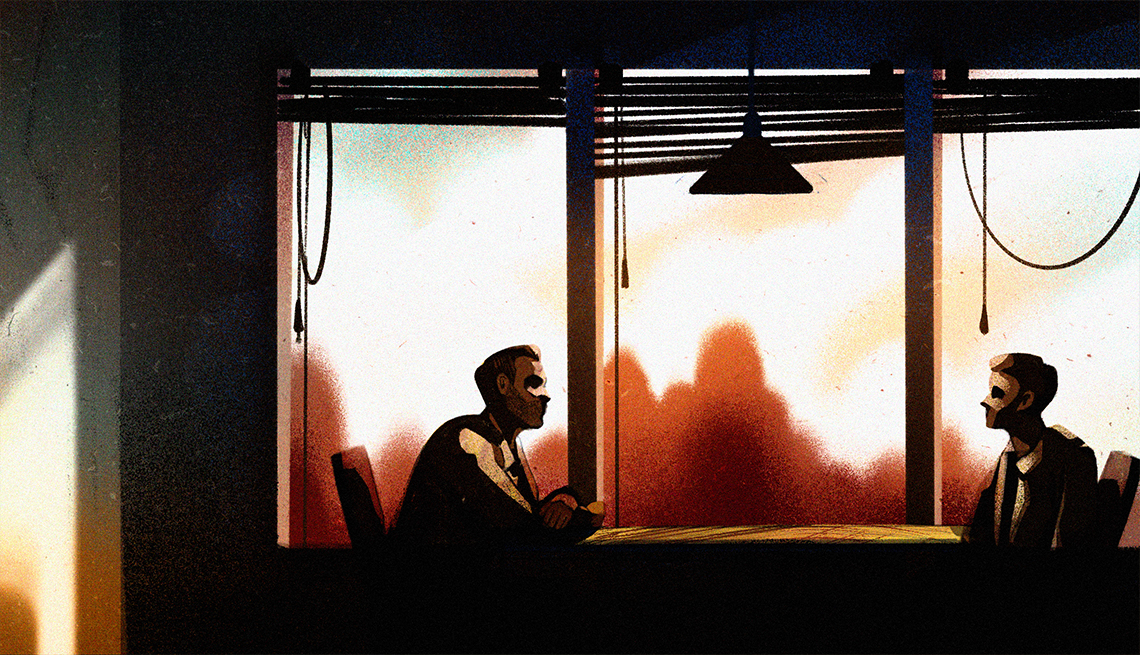

FOR THE FIRST TIME HUGH Price had the five o’clock shadow of a TV detective, and his jacket was rumpled. They were in a small interview room, the ocher walls glossy and cracked, the only furniture a scarred wooden table with two chairs. He sat down in one chair, gestured to the other.

“Thanks for seeing me,” Matthew said. “I was hoping you could give me advice.” But he couldn’t stop himself from asking first about Karel. Had they made an arrest? Did they have any leads?

“The case is still open. Maybe someone will spot the car.” The detective tilted his head, as if hoping to see it in the distance. “Or the man will be caught for something else: shoplifting? speeding? Of all the crimes reported every year, I’m sorry to say, we’re lucky to solve half of them.”

Matthew had heard this statistic before. Now he thought what would it be like if his father bungled half his jobs, or his mother lost half her cases, or he gave half the customers at the Co-op the wrong change? Unzipping his jacket, he offered his sole morsel of information: the morning Karel was attacked, Tomas had been playing with trains.

“So he’s a train junkie!” Hugh Price smiled his triangular smile. “How did you find out?”

He mumbled something about running into Tomas at the Co-op, how they had ended up collecting for Oxfam, keeping an eye out for the car. Across the table the detective registered every ounce of his confusion.

“Matthew, this man is violent, maybe a psychopath. You’re a good-looking boy, around the same age as Karel. I can’t stop you from collecting for Oxfam, but you and Tomas ought to stick together. No peering in garages, thinking you’re Inspector Morse.”

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members