AARP Hearing Center

Five

Matthew

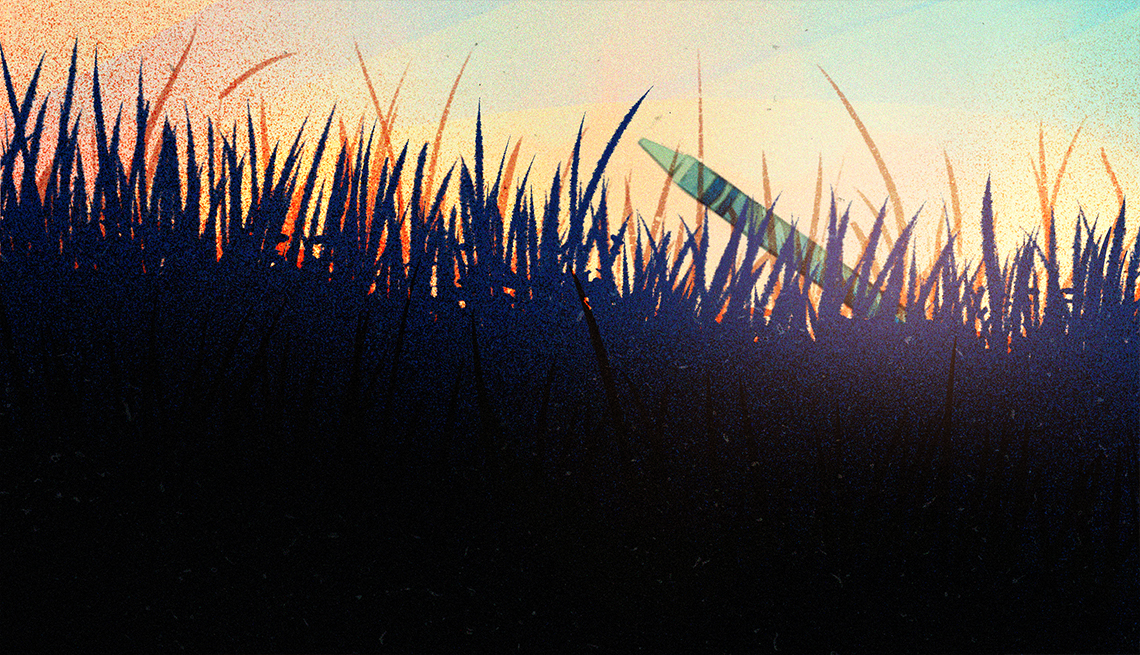

HE HAD WORRIED he might not recognize the gate, one among many, but a loop of yellow police tape hung helpfully from the top bar. He wheeled his bike into the field and leaned it against the hedge. The bales were still there, mysteriously larger. The oak tree looked the same, dark and burly. No swallows today—had they already left?—but two magpies strutting across the stubble, tails jerking. On the grass near the gate lay a gray stick, abandoned by some hiker.

He carried the stick over to where he remembered the boy lying and began to circle it. All day he had imagined finding something significant: a key, a pair of spectacles, a business card reading John Smith, Assailant. In the books he read, there were always clues. His father had told him the word “clue” came from the Anglo-Saxon for thread, and that was what he was looking for, a thread that would lead him from something small, something everyone else had overlooked, to another thing and another, each a step closer to finding the assailant. Scrutinizing the ground, he saw only grass, knobbly soil, straw, pebbles, rabbit droppings.

The month before, on a picnic, his mother had lost her wedding ring. One moment the five of them were talking and laughing. The next they were crawling around, searching. Nothing. Nothing. Then Zoe had exclaimed “Here it is,” and they were all laughing again, the gap between disaster and happiness instantly closed. He picked a few blades of grass and slipped them into his shirt pocket. When he got home, he would write the date on an envelope and seal the grass inside. He pictured men in uniform on their hands and knees, with magnifying glasses and metal detectors. If there were anything to find, wouldn’t they have found it? To his left he saw a flash of black and white: the magpies taking flight. The air shifted, and the first drops of rain fell.

Near the hedge he discovered an empty beer bottle, coated with mud, a crumpled page from a comic Zoe used to read, and the dull blue rectangle of a local bus ticket. The last he put into his pocket, beside the blades of grass. He was walking back to the gate, the soil already darkening with rain, when he remembered the stick. Turning to retrieve it, he caught a glint of silver. There, beside a tuft of grass, lay the boy’s silver chain. It must have fallen, unnoticed, as the paramedics carried him to the gate. When he picked it up, he saw that the chain held a medallion the size of a ten-pence coin: a man fording a river with a small haloed figure on his shoulder.

***

AT HOME HE HEADED TO Zoe’s room, eager to show the St. Christopher. She was at her desk, doing homework; Duncan was lying on her bed, drawing. “Hi,” they both said without looking up. One of Matthew’s earliest memories was of the day his parents had brought home a tiny being with silky hair and perfect hands. His new brother had gazed, waveringly, at some distant view. Then his brown eyes had found Matthew and settled on him with a look of deep attention. Now, watching Duncan’s pencil move across the page, he could not remember the last time his brother had visited his room. Had he been curt? Preoccupied? As he zigzagged through the clutter on Zoe’s floor, he vowed to make amends. He picked up the dictionary on the window seat, and sat down.

Duncan’s pencil paused. “What does ‘raped’ mean?” he said.

Christ, thought Matthew. How to explain? He opened the dictionary, searching for the Rs, but Zoe was already offering her definition.

“One person,” she said, “usually a man, forces another person, usually a woman, to do it, but it’s not really doing it.”

“You do it”—Duncan started to draw again—“ but you don’t?”

She walked over to the bed. “Give me your hand.”

Matthew watched as she began to squeeze, at first gently, then more and more tightly until Duncan cried “Stop.”

“Like that. Something that can be good becomes bad because only one person wants it. Do you think”—she twirled so that her hair flew around her shoulders—“ the man would have stopped to give me a lift?”

Last spring, when she and Matthew missed the bus, she had been the one to hold out her arm and smile at the invisible motorists rushing by. Barely a dozen cars passed before a woman pulled over. As she accelerated back onto the road, she had asked if their parents knew what they were doing. “Yes,” Zoe had said, so quickly that all Matthew could do was nod.

“Zoe,” he said now, “you’re mad. Whoever did this was seriously messed up. He would have driven right past you.”

“Because I’m not pretty enough? Old enough?”

Looking at her bright top, her faded jeans, he recalled his father’s admonition. She had changed so much in the last year, and in the few days since they knelt in the field, she had changed again. Perhaps something had traveled from Karel’s arm into her outstretched hand. He knew of several boys at school who liked her. Would they stop liking the new Zoe? Or like her even more? He suspected the latter.

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members