AARP Hearing Center

Seven

Zoe

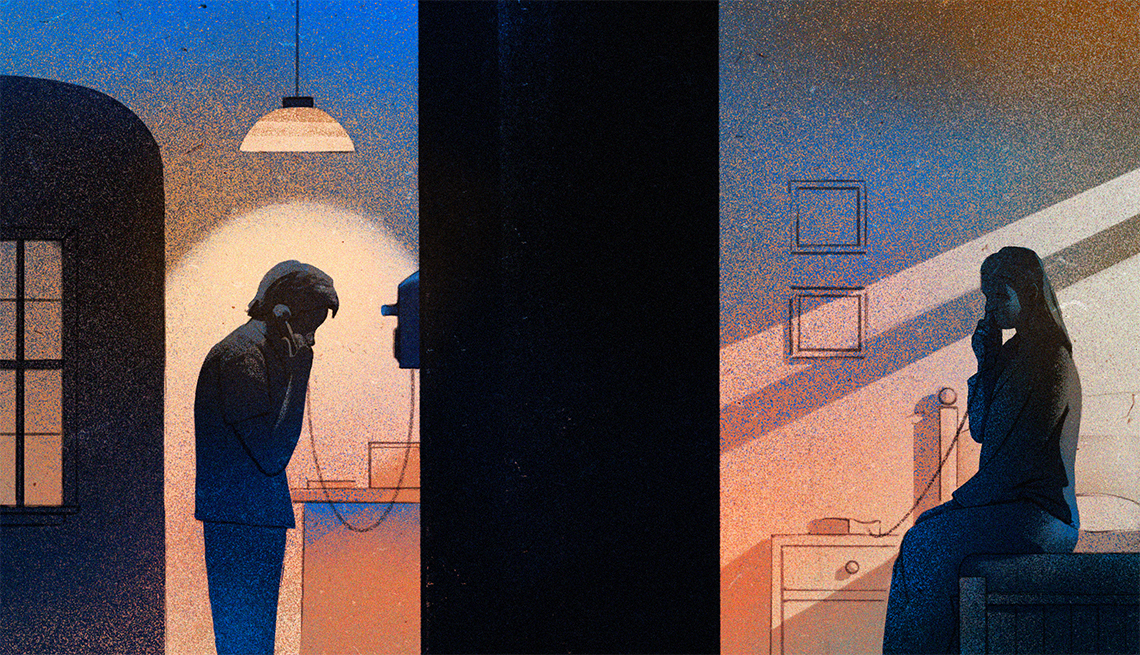

AS SHE LAID HER BIKE down on the grass, two rabbits darted for the safety of the hedge, white tails flicking. The bales were gone; the stubble, beneath windy skies, was a dull brown. Perhaps Karel, in his blue shirt and black shorts, had paused here, experiencing his first twinge of doubt. Most of the time, Zoe thought, we behave as if everyone is going to follow the rules. If a man appeared here now, say the man from the churchyard, what could she do but run? Or submit.

She spread out her poncho and sat down in the lee of the hedge, a few yards from where Karel had lain. She had never told anyone, not even Duncan, to whom she told most things, about these moments when she left her body. Even the word “moment” was wrong. She slipped between the teeth of time. She could still conjure what she recalled as the first occasion. She was sitting on the beach, looking at the waves, holding a piece of seaweed in one hand, a whelk in the other. Her parents thought she was sitting quietly for once, but she was hovering nearby. She could smell the salt air, see the waves glinting and the sand with its Morse code of seaweed and shells, feel the sunlight but she was no longer tethered to a single source of sensation. Then she was back again. The whelk had left an oval mark on her palm.

She couldn’t make it happen. Sometimes it didn’t for months, and she worried she had lost the knack. Then she would leave again. Now she waited, hoping to catch some reverberation, however faint: an aftershock. Nothing. A rabbit. Nothing. After fifteen minutes she was bored, and cold, and entirely sure that she was not leaving her body today. Walking back to the gate, she saw a pale-green crayon lying in the grass.

***

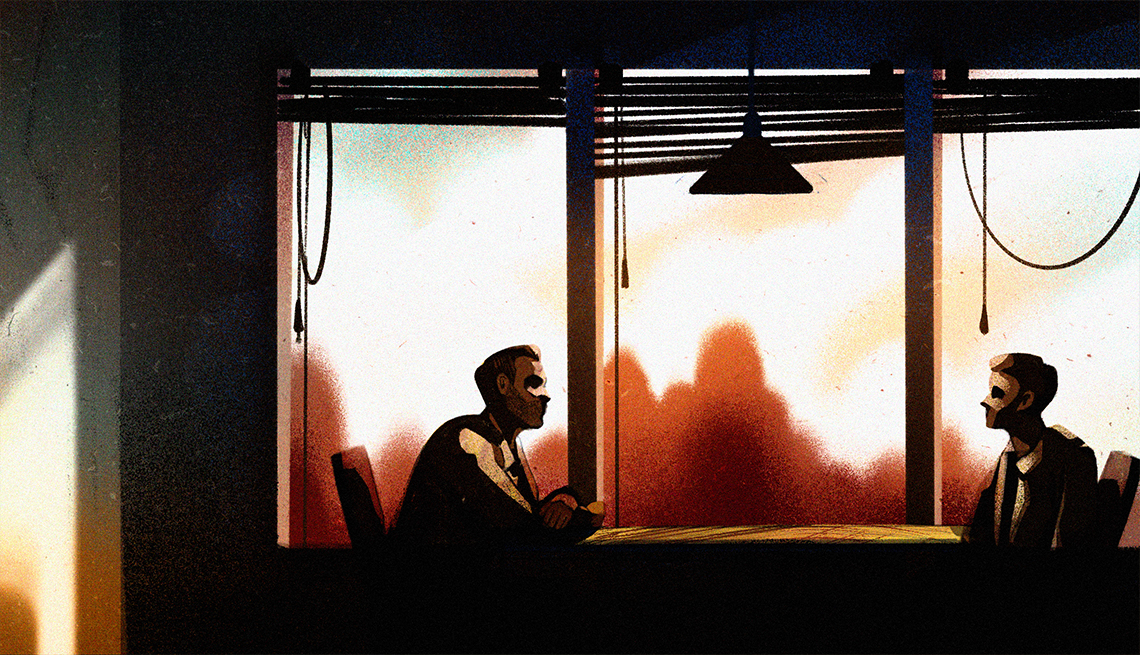

DUNCAN WAS IN THE KITCHEN, eating toast glistening with plum jam, reading a book.

“You left this in the field,” she said.

“Thanks.” He set the crayon beside his plate.

“What were you doing there?” She wanted to be angry—why had he gone without telling her?—but as usual he had disarmed her.

“I just wanted to see it again.” He held out half the toast, and she took a bite.

“Me too. It’s weird that the police haven’t found the man.”

“Not really. They never figured out who broke the window in the school cloakroom, and that’s in the middle of town.” “I thought being there I might”—she eyed the crayon—“ sense something.”

Duncan took a last bite and ran his finger round the rim of the plate. “Maybe too many things have happened in the field,” he said. “Like this house. Think of all the people who lived here before us, and some of them must have died here, like Granny. Sometimes I think I hear her talking, but I can’t make out the words. Do you ever hear her?”

“No.” But as she went to make more toast, she recalled how once or twice, as she drifted into sleep, she had caught stray words and phrases wafting by. “Now you’ve told me,” she said, “I’ll listen harder.”

***

THE NEXT TIME SHE WENT to Oxford, she looked not at shop windows but at men, those alone and those with women; in some ways it was easier when they were with women. Had one of them lured Karel into the field? Her eyes flicked over a man close to her father’s age, a boy around Matthew’s. Neither looked like a bad person, but what did a bad person look like? Her father’s last apprentice, Freddy, had a nicely freckled face and whistled while he worked. But one day the police had arrived at the forge; Freddy had been borrowing her father’s tools to steal scrap metal.

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members