AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Thirty-One

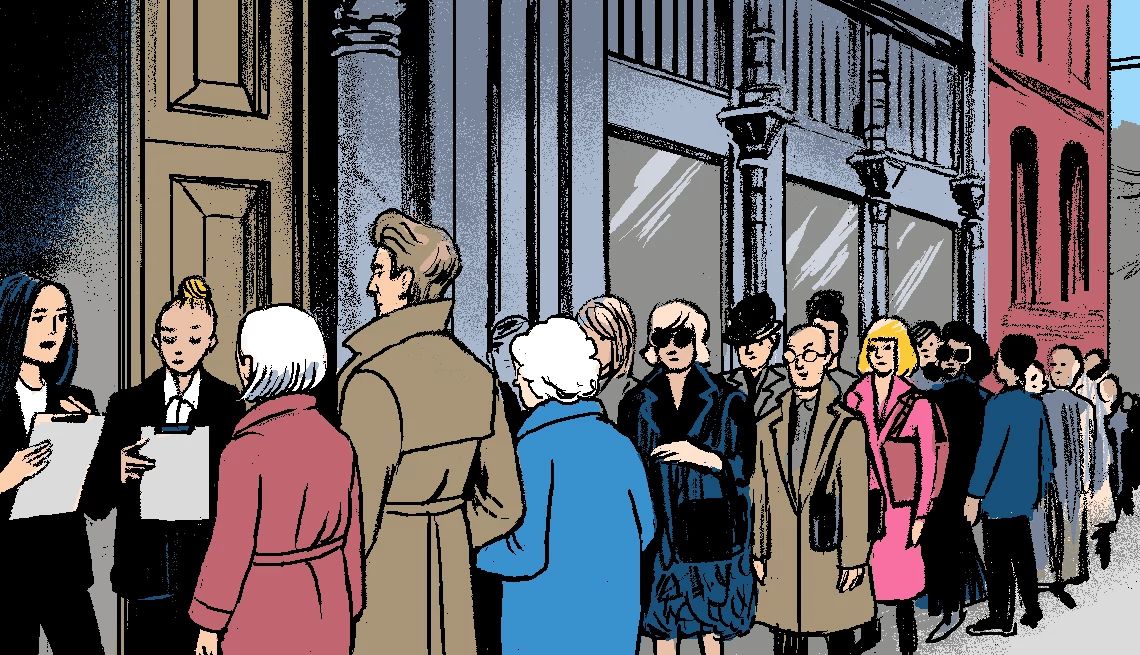

When Archie and the sisters arrived at the Brice-Petitjean auction house for the party, a line of eager guests was already stretching halfway down the street. Clearly the launch of Stéphane’s early twentieth-century jewellery sale was a hot ticket, so Archie was especially gratified when one of two young women with clipboards made a beeline for Penny and Josephine. “The Williamson sisters?” she asked. Archie was impressed, though to be fair there weren’t many other nonagenarians in the queue. “And your great-nephew Archie? I’m Natalie. I’ve been asked to look after you. Please follow me.”

They were swept past the queue, which contained a number of faces Archie recognised from the French magazines he’d flicked through on the Eurostar. There was a photographer waiting in the lobby to capture the celebrities in front of a huge collage of black and white photographs of the much-loved late actress whose collection formed the bulk of the sale. Natalie tried to arrange Archie and his great-aunts in front of it. Archie put on his best smile but Josephine and Penny kept walking.

“Don’t you want a lovely photographic memory of tonight?” Archie asked. “With your spanking new medals?”

“Sometimes it’s best to let memories fade,” said Penny. “Who even needs to know we were here?”

Well, that was one way of looking at it. Archie posed for a couple of snaps by himself to show willing then skipped to catch the sisters up.

Natalie found Archie and the sisters three seats around a small table and went to fetch them champagne. Spotting Stéphane on the other side of the room, Archie waved excitedly. To his obvious delight, his old flame came right over. There was much “bise-ing,” which left both Archie and Stéphane bright red with blushes. The sisters shared an indulgent smile. They’d always had high hopes for Stéphane.

“Aunties!” Stéphane had earned the status of honorary great-nephew over the years. “How beautiful you both look this evening. I must have a closer look at your new accessories.”

He gently lifted Penny’s Légion d’honneur away from her lapel. “Fabulous. Such an elegant design. And you both wear it so well.”

“I agree,” said Archie.

“Well done, Archie, for finding such a good excuse to bring your wonderful great-aunts to Paris to see me,” Stéphane said.

Archie glowed—everybody noticed—but unfortunately his bliss was to be short-lived.

“I’m so glad you’re all here tonight because I want to introduce you all to someone special. You know how much your opinion matters to me. Especially yours, Archie.”

Stéphane beckoned to a man who was holding court in a circle of admiring young women. The chap’s face was familiar. Possibly because they’d seen him glaring intently from every newsstand in Paris. Catching Stéphane’s signal, he excused himself and sauntered across to join the Williamson party.

“This is Malcolm,” Stéphane said. “My fiancé.”

“Oh dear,” said Josephine reflexively.

Stéphane was too busy twinkling at Malcolm to have heard, though Penny and Archie both did.

While the rest of the men in the room were dressed in black tie, this Malcolm chap was wearing a somewhat unusual “costume,” to use the old-fashioned term. He was dressed in brown trousers, a rough dun-coloured linen shirt without a collar, and a worn leather waistcoat. The toe of one of his decidedly ancient boots was flapping open and out of the side of his mouth poked what appeared to be a piece of straw. Still, despite his getup, Stéphane’s fiancé looked Archie up and down in a way that suggested he was making comparisons and deciding that he came off better. Much better.

Archie put on his game face and shook Malcolm’s hand. Malcolm was very well-muscled, his big chest stretched that leather waistcoat. When Malcolm released his hand, after pumping it up and down like he was trying to shake Archie’s arm off, Archie had to flex his fingers to get some blood back into them. Malcolm’s overly-enthusiastic handshake had made the old break in his wrist ache. He cradled it protectively, in a stance that was familiar to Archie’s family and friends. He often cradled his wrist when he felt in need of comfort.

“Did I hurt you?” Malcolm asked. His accent was odd. Half-French, half-mid-Atlantic.

“War wound,” Archie quipped. “Old martial arts injury, actually.”

It wasn’t exactly untrue.

“I have heard a lot about you, Archie,” Malcolm said. “But I didn’t know you were a fan of martial arts. I practise taekwondo and capoeira myself.”

Of course he did. “And you?”

“Defendu.”

“Is that a real thing?”

“Yes, actually. But I don’t have the time these days,” said Archie.

“I understand. You have a little gallery in London, am I right?”

That “little” seemed calculated.

“Yes,” said Archie. “In Mayfair.”

Fifteen all. The sisters watched the exchange as though it was a tennis match, their heads turning back and forth. Malcolm kept the straw in the side of his mouth throughout.

“When I am in London, I spend most of my time in the East End,” said Malcolm. “Where the new art galleries are. For the younger energy. Stéphane likes that too.”

It had not gone unnoticed that Archie had at least a decade on his rival.

Thirty-fifteen.

“It’s hard to keep track of the East End,” said Archie. “Half the galleries there have the lifespan of a butterfly.”

Thirty-all.

“Better a butterfly than a dusty old moth.”

Forty-thirty.

Stéphane, who had been pulled away by a staff matter, was back. He rested one hand on Malcolm’s arm and the other on Archie’s. Archie flexed his bicep as hard as he could, without making it obvious that he was doing so.

“How have you been getting on?” Stéphane asked. “I’m so glad that two of my favourite people got to meet at last.”

“Your favourite people?” Malcolm asked, throwing a proprietorial arm around Stéphane’s shoulder.

“Well, of course you’re my very favourite, dear ...”

Game Malcolm.

“Did Malcolm tell you he’s an actor?” Stéphane asked then, which explained the posters. “I was actually especially looking forward to introducing him to you, Penny, and Josephine, because in his next role Malcolm will be playing a hero of the Resistance. Shooting starts next week. Hence the outfit.”

The ladies cocked their heads in polite interest, pretending they hadn’t noticed there was anything strange at all about Malcolm’s random getup.

“I’m a method actor,” Malcolm explained. “Like Daniel Day-Lewis and Marlon Brando. It means that when I’m working, I live the part.”

“How exciting,” the sisters said in unison.

“I believe that to truly inhabit a role, you have to embrace it twenty-four seven.”

“And your character chews a straw?” Josephine observed.

“He was never pictured without one. René Tremblay was a country man, even when he was defending this very city.”

“Hmmm,” said Penny.

“Shooting begins next week,” explained Stéphane.

“It has been a long and difficult process to get to this stage,” Malcolm continued. “I’ve had to spend a lot of time looking into the abyss and it’s been life-changing. I don’t think I’ll ever be the same again.”

Stéphane put his hand on Malcolm’s shoulder and nodded in sympathetic agreement.

“The rehearsals nearly broke me. The risks. The danger ... I’ve prepared myself for next week like a partisan preparing to die for the love of his country, just as René faced the Gestapo bullets in 1944. The stress has been immense.”

“Of course,” said Penny. “I can see how one might find it almost as traumatic as actually having been there ...”

“Thank you.” Malcolm gave Penny a little “namaste.”

“I knew you’d understand. It’s been tough but I feel I’ve grown as a man and an actor and finally I carry the spirit of the Resistance fighter within me.” He thumped his fist against his heart, then shot it upwards towards the ceiling. “Liberté!”

“Hmmm,” said Archie.

There was a quiet moment while Malcolm and the others contemplated the gravity of his career choices, then Stéphane waved at a new arrival.

“Ladies, Archie, you will excuse us. That’s Dragomir Georgiev over there. I must say hello. I know he has his eye on several pieces for his, er, goddaughter, I think.”

The lizard-like man was accompanied by a young woman several decades his junior. She definitely wasn’t his goddaughter. You could tell that just by looking at her dress. Any godfather worth his salt would have worried about her catching a chill and sent her home to change.

Archie recognised the man. Perhaps a month earlier, Georgiev had visited his gallery and bought five paintings for a new holiday home, or was it a yacht? Georgiev had not spoken at all, sending in one of the flunkeys who encircled him and his “goddaughter” now to complete the transaction the following day. Archie had been sad to let the paintings go, sure that Georgiev was buying them for bragging rights rather than anything about the paintings in themselves. But then you didn’t have to work in the art world for very long to realise that most of the people who could afford to buy the really good stuff had no idea why it was so good. Neither did they care to know. They merely went by the price tag. When guests admired their new paintings, they would be itching to reveal how much they’d paid, not to point out the tiny details that obsessed a real art lover, like Archie.

And now Georgiev was here to splash the cash in Paris. Cash that came from God only knew where. At one point he’d been in politics in some ex-Soviet country, thought Archie, but since then? The kind of money Georgiev had didn’t come from after-dinner speeches.

“Come on, Malcolm.” Stéphane grabbed his fiancé by the big, beefy arm. “I know he’ll be very pleased to meet you.”

“Oh dear,” said Josephine again.

The evening was not unfolding in the way Archie and his great-aunts had hoped or expected. With Stéphane and Malcolm gone, Archie knocked back his flute of champagne—and he never knocked back a drink—and held his glass out for a refill when a waiter passed.

“It won’t last,” Josephine assured Archie as from a distance they watched Stéphane introducing Malcolm to his most esteemed (for which read “wealthiest”) guests.

“But Stéphane is going to marry that man. He loves him.”

“There are all sorts of reasons for getting married and not all of them have to do with love. Doesn’t he remind you of Macadam?” Penny asked Josephine.

“Malcolm? Oh yes.” Josephine laughed. “Yes, indeed.”

“Who’s Macadam?” Archie asked.

“We must have told you about him, dear. He was your great-grandfather’s prized Highland bull. Terror of the Glens. Big muscles. Great hair ...”

“Thick as mince,” added Penny. “Which is I suppose how the poor thing ended up ... I mean, all that guff about how hard it is to play a Resistance hero. I ask you.”

“Quite,” said Josephine. “He’s very pleased with himself. And self-praise is no recommendation.” Penny chimed in with that last sentiment. As did Archie. It was one of their favourite sayings.

The sisters were trying to cheer Archie up but they hadn’t raised a smile. “Toujours gai,” Penny reminded him, with a squeeze to his knee. “Plenty more frogs in the pond.”

“You can’t say that in Paris.”

“I believe I just did.”

It wasn’t often that Archie’s great-aunts couldn’t coax a smile from him but their efforts that evening were in vain. Archie’s disappointment went deep. It wasn’t only that Stéphane, who had occupied a place in his heart for so very long, had finally chosen another. It was the kind of man he had chosen. So ... er, basic (wasn’t that what the modern kids said), with his muscles and his hair and his big white teeth that he’d probably bought in Turkey. He hadn’t taken his method acting so far that he’d let his teeth get stained, Archie bitterly observed.

On several occasions over the years, Stéphane had openly admired Archie’s style—the impeccable forties suits, his insistence on old-school elegance in style and manners—but here was the truth of it. Despite any number of old adages that maintained that looks didn’t matter, they really did. They really, really did. Stéphane had never looked at Archie like that—the way he looked at Malcolm now. Stéphane had fallen in love with a handsome meat-head.

Archie’s wrist still throbbed from Malcolm’s furious handshake, as if to remind him that he would never be able to bench press his own body weight. Or even the body weight of a small dachshund, without feeling a warning tweak in his badly-healed ulna. He wished he hadn’t come. Why hadn’t Stéphane told him about Malcolm before, so that Archie could have made his excuses and avoided this awful moment altogether?

“Aunties, you know what, now that we’ve seen Stéphane, why don’t we just go back to the hotel? He’s very busy. You’ve both had a long day and I’m sure you’d be happy with a nightcap and early to bed, wouldn’t you? I shouldn’t have dragged you here. Shall we skedaddle?”

Josephine seemed quite happy with the idea but, to Archie’s surprise, Penny shook her head.

“No, Archie, no,” she said. “If meeting Stéphane’s fiancé has made you feel like leaving, then we absolutely must stay. At least for a little while longer. Otherwise, it will be perfectly obvious what’s going on.”

Rats. Auntie Penny had rumbled him.

“This is just like that birthday party in Hyde Park in 1993 when you wanted to take your cricket stumps home because a little girl had bowled you out,” she added.

“That girl cheated,” Archie insisted.

“That might well have been the case, but you did yourself no favours by storming off the pitch in a fit of pique. And that’s exactly what it will look like you’re doing if you insist on leaving this party now.”

“I’m very happy to go. You can use me as an excuse,” said Josephine. “Absolutely not,” said Penny. “Archie Williamson, don’t you dare let that knucklehead get the better of you. We ’re staying for at least another half hour and we’re going to look like we’re really enjoying ourselves. Fake it ’til we make it. Come on, laugh!”

She faked a guffaw and tried to get Archie join in. He didn’t.

“If we’re staying, I need some more champagne,” said Josephine.

Archie pulled himself up, straightened his shoulders and, muttering “toujours bloody gai,” he set off to find a wine waiter.

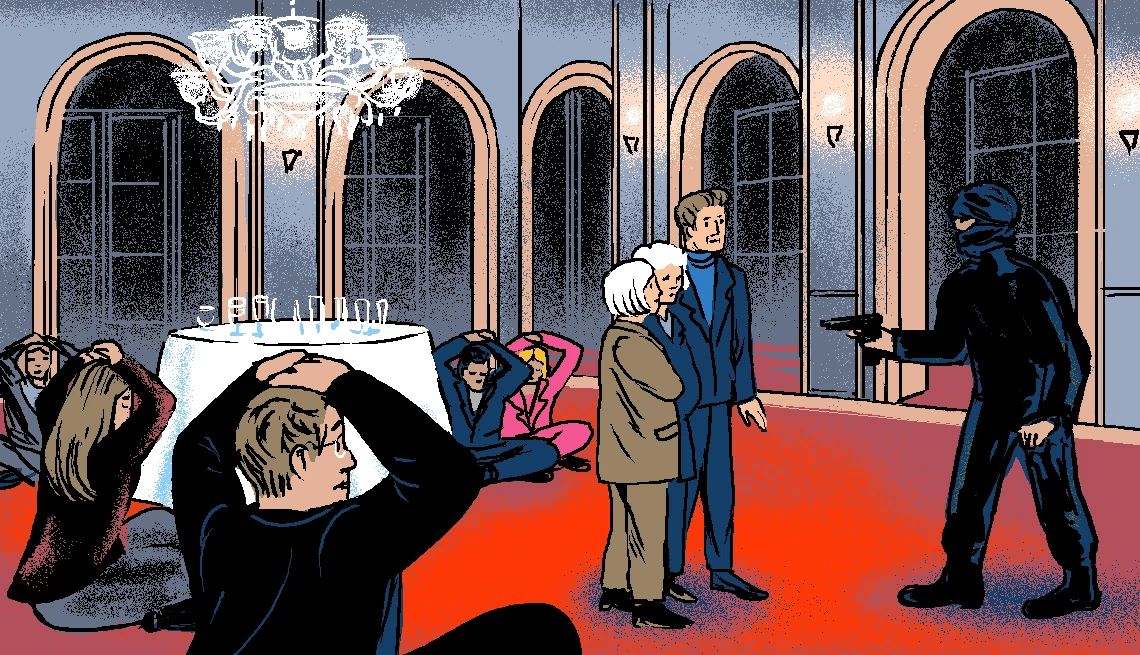

LATER, WHILE ARCHIE wistfully watched Stéphane’s progress around the room and Josephine was in conversation with Natalie about the canapés, Penny surveyed the reception with a practised eye. She imagined it must be reaching peak capacity by now. Chatter filled the room, bouncing off the walls and glass cabinets so that it was hard to pick out any one conversation from the many dozens in different languages that were going on around her. Penny scanned the other guests, using the skill that her husband Connor had so admired, to pick out the embedded security from the genuine punters. It wasn’t hard. While the punters greedily sank the free champagne and twittered and preened, the security team were staying sober and alert. Not so alert that they gave Penny a second glance, however. Why would they? She was no threat. A woman her age was used to being disregarded. Had been for many years.

Hold on, she reminded herself. That’s what you thought in Peter Jones.

That bloody crystal elephant, which Penny had to pretend she adored for dear Archie’s sake, was an ugly reminder that she must not make too many assumptions. “Never forget.” She had to employ the same care as she had when she was just starting out, back in the 1940s.

“Check the room again.”

The three chaps in almost identical black suits, standing by the buffet table, were definitely security. They weren’t drinking. One of them kept putting a forefinger to his ear. Badly-fitted earpiece? “Must keep an eye on the whereabouts of those three at all times,” Penny decided. But now was the moment, while everyone was so excited and distracted and before Stéphane brought the hubbub to a halt by getting up on stage to make a speech.

While Archie was making small-talk with another guest and Josephine was off spending another penny, Penny got up. No one watched as she crossed the room with determination in her small blue eyes. She was just a little old lady, drifting through the crowd of the young, the beautiful, and the rich, as though she were already a ghost. She was invisible and that was how she wanted it.

Slowly she made her way to the table where lots seven to thirteen were on display. Lot thirteen was an eighteen-carat gold ring mounted with an eight-carat emerald surrounded by three-carats’ worth of diamonds in a peerless ballerina setting.

Penny stopped in front of the toughened glass case and murmured, “We meet again.”

Chapter Thirty-Two

Antibes, 1966

“Penny? Penny Williamson? Is that you?”

Penny spun round, alarmed at the sound of her name, and looked about the hotel lobby for this person who thought he knew her. She could see only a very tanned middle-aged man with no hair, wearing a pair of overly tight white trousers.

He opened his arms as he walked towards her.

“Gilbert?”

“Penny! It is you. I knew it. You have not changed at all.”

Penny wished she could say the same. She was still trying to reconcile the man standing in front of her with her childhood friend and long-ago lover. While he had no hair left on his head, Gilbert Declerc was sporting an extravagant moustache that put her in mind of the fox fur tippet she’d recently inherited from one of her godmothers. Full of moths, the horrible thing was. That bequest had cost Penny half her cashmere.

“But what are you doing here?” Gilbert asked.

“I’m on honeymoon,” Penny said, wishing that Connor could be on time for once.

“Well, this is a happy coincidence! I’m on honeymoon too. Isn’t this wonderful,” Gilbert said, leaning in close so that she was almost overwhelmed by his cologne. “Two old lovers meeting like this. Imagine how embarrassing it would have been were I newly married and you still the spinster.”

“Quite,” said Penny, tightly.

“But where is he, this lucky man, who has captured the heart of England’s most beautiful rose?”

Where was he indeed? Even before Gilbert turned up, Penny was starting to worry as she always did whenever Connor went to “see a man about a horse.” It was worse since the hotel was buzzing with news about a violent gang that was targeting foreign tourists heading to their hotel knowing they would be laden with cash to pay for their accommodation. The Grand Hôtel des Anges would not take cheques or Connor’s new-fangled credit card. Everyone wanted to see that card but nobody would accept it.

“Ah! Here is my wife.”

Gilbert motioned towards a young woman who was standing just inside the hotel doors, scanning the lobby myopically through big red Lolita-style sunglasses. She was carrying an enormous number of bags. Behind her came one of the doormen, pushing a trolley piled high with more shopping. As Penny watched, the young woman skidded on the polished marble floor of the lobby, which was death to anyone in smooth-soled shoes, and dropped half her haul. Before Gilbert could get to his wife and offer his support, another man was already by her side, crouching down on the floor next to her, helping to gather up her scattered packages.

Connor.

“Of course,” thought Penny. Where there was a mini-skirt ... She shook her head as her incorrigible husband gazed at the young woman with his best “smiling” Irish eyes.

Gilbert looked distinctly uneasy as he raced to rescue his newly-minted spouse. Penny was right behind him.

Gilbert pulled his wife to her feet and crouched down to finish picking up the mess. He locked eyes with Connor, who was still twinkling. Penny gave Connor a little shove with the toe of her sandal, a signal that he should stand up now, before Gilbert suspected him of looking up his wife’s dress. Penny made the introductions. “This is my husband, Connor O’Connell. Connor, this is Gilbert Declerc. We knew each other as children.” The phrase “as children” put him firmly in the past and, in Penny’s mind at least, erased that awful, embarrassing week in 1947. Definitely best forgotten.

“I’m Veronique,” said Gilbert’s wife, gently offering Penny her right hand, which was as delicate as the rest of her doll-like self. Her insubstantial hand and wrist were weighted down by the jewels heaped upon them: three impressively thick diamond eternity bracelets and a ring with an octagon-cut sapphire. Penny had to try hard not to stare at it. It dwarfed the sapphire she was wearing on her own left hand. She knew Connor would have noticed it too.

The two couples stood in the lobby for a little longer, making small talk. though Penny could not wait to get away. She could feel Gilbert’s eyes upon her, appraising her, deciding whether the chassis had aged as well as the bonnet. He was appraising Connor too, though she was less worried about that. For some reason Connor was the kind of man men liked.

Then, to Penny’s horror ...

“You must have dinner with us tonight,” said Connor.

“But they’re on honeymoon,” said Penny quickly. “I’m sure they want to be à deux.”

“We ’re on our honeymoon too,” Connor reminded her. “They’ve got the rest of their lives to be à deux. As have we, my darling. It isn’t every night you bump into one of your childhood friends. You must have a lot to catch up on.”

Penny inwardly winced but meeting eyes with Connor she knew she shouldn’t continue to protest. Let Gilbert make the decision for all of them. She had a feeling that decisions weren’t the lovely Veronique’s department.

“That would be very nice,” said Gilbert.

“Good choice, my man.” Connor clapped Gilbert on the shoulder. “I’ll have the concierge reserve a table for four in the restaurant tonight. Have you tried the sole meunière here, Veronique? It’s by far the best I’ve ever tasted.”

CONNOR O’CONNELL HAD all the patter. A one-time jockey from County Kildare, he’d ridden horses for the great and the good: Saudi princes, European royalty, even the Queen. His reputation in racing circles was of a man who made winners. He could have ridden a donkey to victory in The Gold Cup at Cheltenham. At least, that was the way he told it.

When the news broke that Connor was going to marry Penny Williamson, there were expressions of open-mouthed surprise up and down the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. It was widely believed that at almost forty-five, Penny Williamson remained unmarried because she “was not that way inclined.” Meanwhile, Connor was a notorious bachelor. No woman could tie him down. Then along came Penny and Connor was smitten.

You Might Also Like

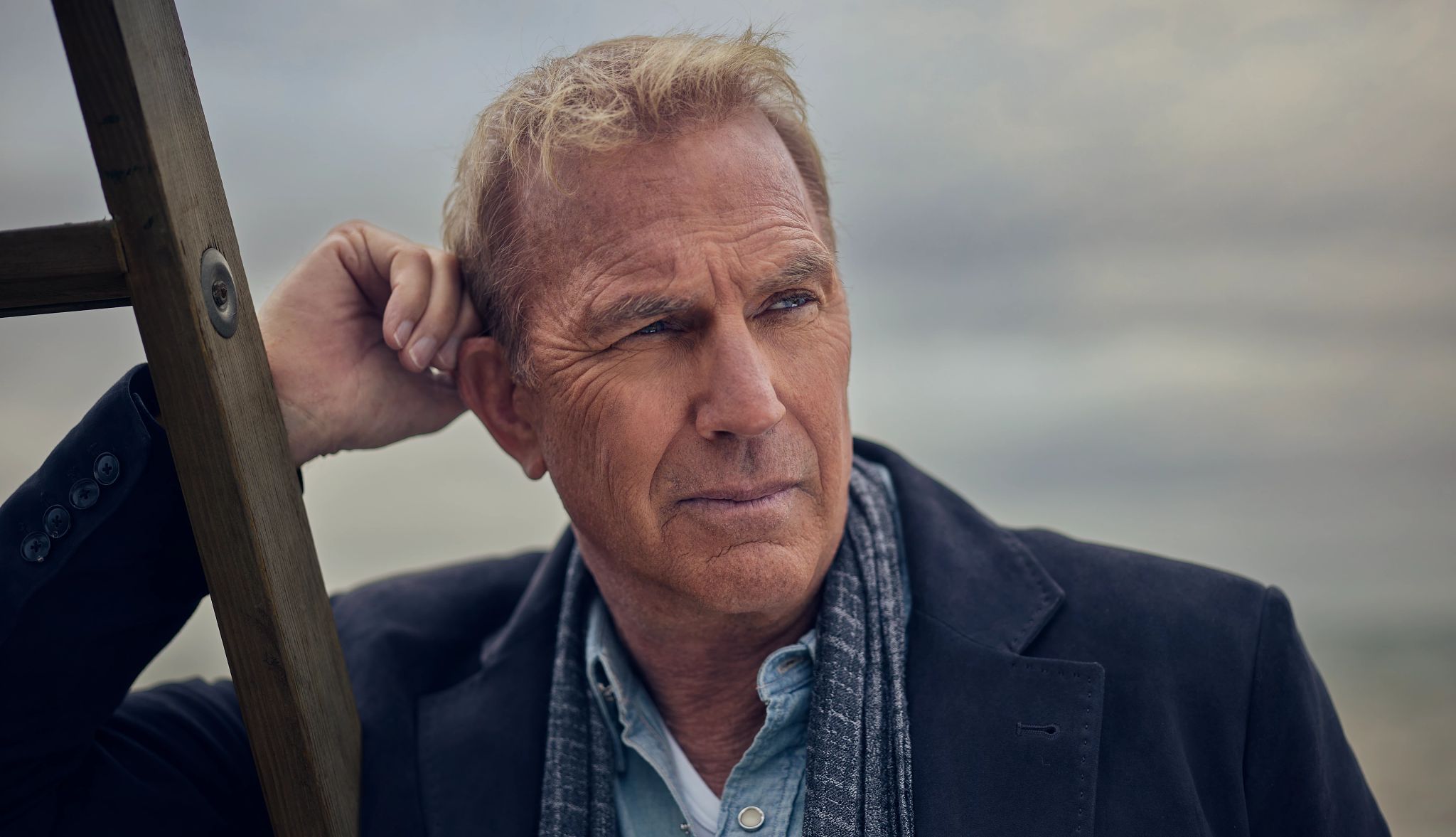

Meet ‘Excitements’ Author CJ Wray

This long-time romance writer was inspired to switch genres by real-life sisters still having adventures in their 90s

Free: James Patterson's Novella ‘Chase’

When a man falls to his death, it looks like a suicide, but Detective Bennett finds evidence suggesting otherwise

More Free Books Online

Check out our growing library of gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety

More Members Only Access

Enjoy special content just for AARP members, including full-length films and books, AARP Smart Guides, celebrity Q&As, quizzes, tutorials and classes

Recommended for You