There’s every need to swear!” Jane responded. She followed up with a few more carefully chosen curses.

“Where is Josephine?” Maureen asked this time. “We all need to be downstairs.”

Still Josephine didn’t move. She was so very unhappy. Perhaps it wouldn’t be so bad if the Luftwaffe did their worst and she didn’t make it to the shelter.

There was a banging right on the bathroom door now. It was Iris.

“Josephine, come on.”

The whistling noise they had all come to dread was followed by an awful crump—close, very close by—that made the whole building shake.Iris hammered on the door again.

“They’re flying right over us. Come on, you goose. I don’t want to die.”

I do, thought Josephine. And I deserve to.“

Josephine,” Iris shouted through the door. “It isn’t fair to make us worry. Come now.”

“I’ll be right down,” Josephine promised.

She heard Iris thundering down the stairs. Somewhere nearby, another stick of incendiary bombs made contact. Maureen shrieked. Jane cursed all the saints.

“I’ve had enough,” Josephine looked at her reflection in the mirror as she spoke to her own god. “I don’t want to live anymore. Put me out of my misery. I know I can never be happy again so I’ll be grateful to be dead. Just make it quick and don’t hurt the others. They’re good girls. Not like me.”

Someone seemed to be listening. A moment later Josephine heard a German plane right above the house. She closed her eyes and waited for the inevitable.

Down in the cellar, the young Wrens said their prayers and crossed their fingers, pleading for salvation like the children they’d been not so very long ago.

THE ALL CLEAR did not sound for what felt like an eternity. When it did, with barely a word to one another, the Wrens climbed up from the cellar and filed out through the front door of their house to see the devastation on the street. Their street. The Germans had never got so close before.

The smell of cordite, which had filled the basement, was just as strong outdoors. The air was thick with smoke and choking dust. Opposite, where a big house that exactly mirrored the one in which they were living had stood, was now a smoking ruin. Only one wall of the once grand villa remained intact, revealing fireplaces, wallpaper, and treasured family photographs and paintings still hanging. There was a strange intimacy to the sight of a charred dressing gown on the back of a door that led to nowhere. It was as though a monstrous child had taken a hammer to a dolls’ house.

The fire brigade and the air raid wardens were already there, attempting to move a large beam.“Is someone under there?” Iris asked one of the firemen who was taking a breather on the wrennery steps.

“No one alive,” he said.On the street lay five bodies, carefully shrouded with blankets, awaiting the undertaker.

“It’s a wonder there aren’t more,” the fireman observed.

The Luftwaffe had taken out every other house on the side of the street opposite the wrennery. There was an awful precision to the way the bombs had fallen.Maureen muttered a prayer. Iris and Jane clung to one another. Only Josephine was dry-eyed. Iris folded her into a hug.

“You goose,” Iris said. “We were so, so worried when you stayed upstairs.”

The warmth of her friend’s arms made Josephine remember how long it had been since she’d last been held. When she’d waved her off to London, Josephine’s mother had hardly seemed able to look at her, let alone share one last embrace.

VERA LAUGHTON MATHEWS, the venerable director of the WRNS, was apprised of the near miss and appeared at the wrennery at breakfast time to make sure her girls were as well as could be expected after such a frightening night. Her stalwart presence was reassuring.

After that, the young Wrens returned to their various roles about the city as on any other Wednesday morning. Josephine and Iris caught the bus into central London. The journey took far longer than usual. The Luftwaffe had been busy all over the city and had rendered many roads all but impassable. Iris didn’t chatter away as she normally did but as they turned into Baker Street she grabbed Josephine’s arm, leaning across her to get a better look at one bombsite in particular.

“It’s the cinema,” she breathed. “We were in there just last night.”

The cinema, like the house across the road from the wrennery, had been obliterated. The burgundy velvet seats were scattered throughout the ruins like the seeds of a pomegranate crushed beneath a cart wheel.Iris crossed herself.

“God was looking out for us,” she breathed.

Perhaps he was.

As she looked at the wreckage, Josephine felt the inexplicable sensation of something like the beat of a second heart keeping time with her own. Something like hope.

During her lunch hour, Josephine wrote to Connie Shearer at her Battersea ambulance station, suggesting they meet at the Lyons’ Corner House on Coventry Street on Saturday afternoon. Her mind was suddenly busy with the reasons why Connie might want to meet. She must have news from August—she’d been their go-between after all.

Returning to the wrennery that night, Josephine picked up a tiny piece of shrapnel from the road outside. It was only the size of a cinema ticket, yet she knew that at high speed it might have caused significant damage to the fragile body of a human being. She wrapped that shrapnel in her handkerchief and put it in her pocket. Holding it tightly, like a talisman, Josephine resolved to get through this war and to find August when it was over.

ON SATURDAY, JOSEPHINE got to the Corner House ten minutes early. Fifteen minutes after the appointed time, Connie Shearer was still nowhere to be seen; instead a young man who said he’d been Connie’s colleague arrived in her place to buy Josephine a cup of tea and offer his condolences. He’d wrung his cloth cap between his hands as he told her, “Connie died in the raid on Tuesday night. The house she’d been called to took a direct hit. She didn’t stand a chance.”

The news Connie had been so keen to impart had died with her.

“Will you be alright, miss?” the young man asked nervously as he waited for his message to take effect.

“Of course.” Josephine nodded briskly. She was well used by now to holding back her emotions. She thanked the young man for the tea and left the Corner House with her mascara still intact. But on her way back to the wrennery Josephine had to duck into an alleyway as the tears finally broke through.

She pounded a cold brick wall with her fists.

“Not Connie. You were supposed to take me, God, not Connie. Not Connie too ...”

MORE THAN EIGHTY years later, Josephine pressed her thumb to the edges of her “lucky” piece of shrapnel, safe inside its little cotton pouch, and smiled and nodded and smiled as Archie outlined the excitements ahead. Archie seemed so very pleased about the trip to Paris that Josephine decided she would just have to play along with his enthusiasm and make her excuses later.

“Wonderful, Archie!” she said. “Oh, it will be ever so gai.”

But she didn’t want to go to Paris. If she’d never been to Paris, things might have turned out very differently indeed.

Chapter Nine

Present Day

Paris in June. The timing could not have been better for Archie. As it happened, a trip to the City of Light was already pencilled into his diary for the week of his great-aunts’ inauguration as Chevaliers de la Légion d’honneur. He was due to be in France for a series of antiques and art fairs. The fairs were one of the highlights of Archie’s year. He relished the opportunity to see what was “new” in the world of old paintings and catch up with friends in the business.

Thus when the date for the inauguration came in, Archie was very pleased indeed to see that it perfectly matched his tentative plans. However, almost as soon as he’d told the sisters about the excitements ahead, he started to worry.

It had seemed such a grand idea, taking his great-aunts to France on a jolly, but perhaps he should have asked the French Embassy if they might receive their gongs in London instead. The sisters were in their late nineties, after all.

As it was, Josephine had expressed some reluctance to take the trip but was quickly overruled by Penny, who pointed out that this might be their last hurrah. For his own selfish reasons, Archie had backed Penny up, promising that he would make sure it was all very easy and a smashing adventure, to boot.

“What’s happened to the daring great-aunt I once knew?” he’d asked when Josephine demurred. He’d jollied her into letting him book her ticket. But perhaps Archie should have accepted her concerns. Were the sisters really fit enough to travel overseas for the ceremony? How would Archie make sure they stayed out of trouble if they did?In the week following the news of their election to the Légion d’honneur, Penny had twice walked out of Waitrose on the King’s Road without paying. On the second occasion, she had secreted a tin of sardines in chilli oil in the pocket of the fishing jacket she wore for most casual outings. She didn’t even like sardines! The security staff had been lovely about it, thank goodness. They accepted that Penny’s memory was perhaps not what it should be and made her a cup of tea while she waited for Arlene to come and find her. But Penny’s accidental shoplifting—and of course it was accidental—was becoming a worrying habit. Where had it come from? Archie googled “shoplifting and dementia” and was horrified to discover that it was not at all uncommon for people with dementia to unwittingly commit petty crime. The ubiquity of the phenomenon did not make it any less concerning. What if Penny did the same in Paris and fell foul of a gendarme who didn’t have the empathy of the lovely team at Waitrose? Would Archie be able to talk their way out of that? He realised with a sinking heart that he wouldn’t be able to keep an eye on both sisters and do all the things he had hoped to do. Like seeing his old friend Stéphane.

STEPHANE BERNARD HAD been Archie’s school French exchange partner. When they first met, Stéphane was a sixteen-year-old history geek obsessed with the Renaissance. He now headed up Brice-Petitjean, one of the biggest auction houses in Paris. Twenty-five years had passed since Archie and Stéphane shared their first illicit kiss in the garden of Stéphane’s parents’ house in Annecy but the memory of that day was still special to Archie. He suspected it remained special to Stéphane too. They’d stayed in touch ever since, meeting whenever they found themselves in the same city. On their occasional meet-ups, Archie thought he still sensed a frisson between them but fate decreed they had never been simultaneously single and thus able to act upon it.

By very happy coincidence, Stéphane was hosting a fancy reception the week of the antiques fair to celebrate Brice-Petitjean’s upcoming “important twentieth-century jewellery” sale, which included headline items from the estate of one of France’s most popular actresses of the 1950s. Archie was over the moon to receive an invitation. Though he didn’t know Stéphane’s current relationship status, the fact that Stéphane responded to Archie’s instant RSVP with matching alacrity gave him great hope that this could be the moment he’d been waiting for.

“It will be wonderful to see you,” Stéphane wrote.

Archie knew he simply had to be at that party. But it might mean having to leave the sisters alone in Paris for an evening and in the light of recent events that was just too big a risk. What he needed was a reliable auntie-sitter, so he was extremely relieved when Arlene said that she would love to accompany her charges to France. Worth every penny, Archie thought, as he booked her Eurostar ticket.

With Arlene on board, Archie felt reassured enough to put the rest of the plan in place. He booked four rooms at the Hotel Maritime just off the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. It was expensive but he knew the sisters would love its old-school style. Soon the trip was coming together nicely and Archie dared to start believing he might be in line for some excitements of his own.

OVER SUNDAY LUNCH in South Kensington, the day before they were due to travel, Archie outlined their Parisian itinerary to his great-aunts and Arlene. Josephine and Penny approved whole-heartedly of the booking at The Maritime and the news that Archie had upgraded their Eurostar tickets to Standard Premier class with his carte blanche points.

“We will arrive in time for tea tomorrow afternoon,” Archie told them. “Tuesday is the big day. We need to be at the ceremony venue by nine-thirty in the morning. A French veterans association will be hosting lunch in a nearby restaurant. In the afternoon, you have an interview with the BBC’s Paris correspondent. That might take an hour or so. After that, I expect you’ll both be happy with room service and an early night. Meanwhile, I ... ”

The sisters looked at him expectantly.“

Well, I’ve been invited to a reception at Brice-Petitjean, Stéphane’s auction house ...”

“Stéphane!” Josephine and Penny echoed his name.

Archie’s great-aunts knew all about Stéphane. He’d visited them in London a number of times over the years. They both adored the charming young French man almost as much as they adored Archie.

“It’s to launch a jewellery sale. Terribly boring,” Archie continued. “I won’t drag you ladies along.”

“Oh no,” said Penny. “A reception at Brice-Petitjean sounds right up my street. It seems a shame to be in Paris and not make the most of every moment. I would love to see Stéphane again.”

“Me too,” said Josephine. “Such a lovely young man. Is he single?”

“I’m not sure.”

“Well, you can rely on us to ask the right questions.”

The very idea made Archie blanch.

“So you both want to come to the auction house reception?” he asked them, heart sinking.

Penny nodded. “Yes. Absolutely. That would be terribly gai.”

Archie could only hope the sisters would have forgotten all about it by the time they boarded the Eurostar.

Illustration by Agata Nowicka

Chapter Ten

That same afternoon, Penny packed her suitcase for the trip. Arlene had offered to do it for her but Penny wanted to be sure she had everything she needed and it wasn’t a task she could delegate.

She could hardly believe she was going to Paris the following morning. Thank goodness Josephine had allowed herself to be persuaded.

Had Josephine refused to travel, the whole trip would have been off and that would have been a disaster. Penny felt only a little guilty for having turned on the waterworks when Josephine first expressed her reservations.

“It’s only the thought of excitements like this that keep me going,” Penny had lied.Alone in her bedroom, Penny shook out the jacket she’d bought at Marks and Spencer the previous Friday. Archie had insisted the sisters go shopping for something new to wear for the inauguration, though both Penny and Josephine would have been perfectly happy to wear the same suits they wore for every public occasion. Josephine always wore a navy-blue trouser suit. Penny had a preference for brown. Funny how more than three quarters of a century since they’d left the women’s services, they both still resorted to uniform dressing for important occasions. But Archie wasn’t having it. Not this time.

“One isn’t awarded the Légion d’honneur every day,” he’d reminded them. “You’ve got to be wearing something fresh and modern when you step up to receive those medals. We’re going to Paris after all. It’s the fashion centre of the universe.”

“I think we’re beyond fashion,” Josephine told him.

But the sisters had eventually agreed to some new outfits and Arlene, who was very interested in fashion, had done the honours, escorting them to the Marks and Spencer flagship store at Marble Arch and acting as their personal stylist. At least, she had tried to act as their personal stylist.Josephine may have somewhat submitted to Arlene’s suggestions but Penny had ignored the younger woman’s exhortations that she should go for a “pop of colour” and settled instead for a trouser suit in a dark mahogany shade, which was as close as Arlene would let her get to brown. Entirely plain and polyester, it was the sort of suit one could wear for all occasions—sober or festive. Penny’s first thought, when she spotted it, was that it would make good funeral wear for those tiresome modern occasions when people insisted “no black.”

As Penny emerged from the M&S changing room, Arlene was talking to a sales assistant, explaining why the sisters needed new outfits.

“Ah, bless!” said the assistant, when she saw Penny in the jacket and trousers.

If there was one thing Penny really couldn’t stand, it was people who said “Ah, bless.” Such a patronising phrase and a reliable signifier that the person who uttered it was a half-wit.

“You’ve won a medal, haven’t you?” the assistant added in the tone she probably used for three-year-olds and puppies, compounding her mistake.

“Yes, I know I have, dear,” said Penny. “I may be old but I am not yet entirely gaga so please take your inane ‘ah bless-ing’ somewhere else.”

The assistant pursed her lips and scuttled away to rearrange a pile of cotton sweaters.

“Penny,” Arlene scolded. “That lady was helping us and now you’ve upset her.”

“She needed upsetting.”

The moment gave Penny a small frisson of satisfaction. She hated to be underestimated, even though she knew that was exactly what she would be hoping for in Paris.

+++

"ONE SHOULD ALWAYS pack a party dress,” Penny said to herself now as she folded the suit into her suitcase. “And some sparklers to go with it.”She tossed her old medals in their velvet pouch into her handbag. Then, having taken a quick look out of her bedroom door to reassure herself that Josephine, Arlene and Archie were still downstairs watching—for the hundredth time—a DVD of In Which We Serve, she set to work.Penny’s knees and hips let out a sharp protest as she knelt to roll up the rug on her bedroom floor. It was a beautiful rug. She’d bought it on a trip to India with Jinx, back in the 1950s. Every time she thought about it she was transported to the dingy shop in a back street in Agra, which had looked so unpromising yet was stuffed full of treasures. She remembered the scent of the small glasses of tea they’d been offered and the beautiful young boys who demonstrated how the fine silk threads looked different depending on which end of the rug you were standing. They’d unfurled those rugs with such indifferent aplomb; it was almost like watching a ballet. What a fabulous adventure that had been. The Taj Mahal by moonlight was a sight Penny would never forget. It had been a successful business trip too.

With the rug carefully rolled back, Penny took out her old Swiss army knife and knelt down again to work loose the screws that were holding the floorboard in place. One, two, three, four. The board took some prising up but she managed it without too much swearing or making any other noise that might attract Arlene’s attention. That woman had the ears of a bat. Finally, Penny sat back with a section of the board in her hand. And there was her safe.

Of course, any professional burglar worth his salt would know that beneath the floorboards was the place to keep something really valuable but Penny was happy that this safe would at least escape the notice of a casual thief. There wasn’t much left inside it now anyway. The pieces of jewellery that Archie would recognise as his great-aunt’s favourites were always on her body or in the pottery bowl on her bedside table (it was a very ugly bowl but Archie had made it when he was nine and for that reason alone it was infinitely precious). What remained in the safe were things Penny didn’t ever wear but couldn’t sell, and the thick wad of notes she’d received in exchange for the diamond solitaire she’d lifted on the way to meet Archie at Peter Jones back in April. Not entirely a fair exchange, she suspected, but she was a little out of the loop when it came to finding reliable fences and it was very difficult to conduct such delicate business when Arlene was always first to the phone. Ah well, it was still enough to fund the Foundation’s school in the Democratic Republic of the Congo for half a year.

The cash was not what Penny was after that day, though she would need to deal with it soon. She didn’t want to leave it to Archie. He wouldn’t have a clue how to get it into the Foundation’s bank account without having to answer too many questions. Archie, dear Archie, could not tell a lie, to the extent that sometimes it was hard to believe he was her blood relation. Penny was looking instead for a particular piece of jewellery, something she had not worn in a very long time. Something she had never worn in public.

“Ah! There you are!”

From the corner of the safe, Penny pulled a little newspaper package. She unfolded it and slipped the ring that had been hidden inside onto her finger, surprised to find it so easy. Her knuckles were gnarled and swollen with arthritis, but with just a little effort, she could still get the ring on. She held her hand to catch the light from the window and turned it this way and that so the green stone in the centre sent coloured shards across the white walls. Everything grows old, thought Penny, except for the stones. The Stones! She had a little chuckle at her own joke. She’d met Mick Jagger at one of her husband Connor’s parties, before the band became famous. He’d flirted with her, Penny remembered, suggesting she might like to go upstairs for a quickie. She wondered if he would ask her now. She wondered if it would be worth the bother of saying yes if he did. What was that line? “Come upstairs and make love? These days it’s one or the other.”

The ring had aged considerably better than Penny or Mick Jagger. Its ballerina setting was as pristine as the central stone. The design was timeless. Simple. Not that the simplicity meant it had been easy to create. It had taken a special jeweller to make a setting so fine. It took a trained eye to appreciate the skill. Penny had that eye.

She put on her glasses and brought the ring closer to her face. It was as good as she remembered. Briefly, her mind flashed back to the first time she’d seen it, on a velvet tray in a jeweller’s workshop. She could see the jeweller’s face as he waited for her to tell him what he already knew. It was perfect.

“An excellent idea,” he’d told her. “To have a replica made of such a fine piece.”

If only she had the original.

With the ring on her finger, Penny flattened out the newspaper cutting in which it had been wrapped. The scrap of paper dated from June 1966. It held a story that had been tucked away on page eight of The Times.

“French police are searching for a mysterious benefactor who left an emerald ring in a church in Antibes on the Côte D’Azur. The woman visited the church’s confessional at around three o’clock in the afternoon before depositing the priceless gem in the offertory box on her way out. She is described by a witness as well-dressed, of medium height, wearing a scarf over her light brown hair. She spoke perfect French with a slight English accent . . .”

Just then Penny heard Arlene in the hallway downstairs. The film must have finished.

“I’ll get us all some tea,” Arlene said in the loud voice that suggested Josephine’s hearing aid was on the blink. “I’ve got a special treat as well. I’ll ask Penny if she’d like to join us.”

Penny wrenched the ring from her finger and quickly tucked it into the breast pocket of her shirt. She just about managed to stand up and kick the rug back into place before Arlene got to the top of the stairs. She’d have to nail the floorboard down again later. Arlene knocked lightly on Penny’s door. She was good like that at least. She would never just barge in.

“Tea and lemon drizzle?” Arlene asked when she popped her head around the door.

“Oh, yes please,” said Penny. Arlene made excellent cakes.

“And you asked me to remind you about the five-thirty at Haydock Park. I put that money on Carningli like you asked.”

“Thank you. Let’s hope the old nag isn’t having an off day.”

Penny still had the Racing Post delivered. Connor’s lessons in how to read form had proved invaluable over the years. She remembered how he’d called her a “natural” when it came to picking horses. Penny could read things in a horse’s body language that other people missed. She always thought she could read things in human body language that other people missed too. Until she met Connor.Arlene was hovering and Penny was sure she was looking at the rug.

Had she put it back the wrong way round? “I’ll be downstairs momentarily,” she said.

Thankfully Arlene understood she was being dismissed. With Arlene gone, Penny fished out the ring and gave it one last appraising look before she secreted it more securely in the inside pocket of her handbag next to her lucky silver matchbox. She wasn’t going to Paris without that.

THE LEMON CAKE was excellent and Carningli romped home two lengths ahead of his nearest rival.

“Wonderful.”

Penny clapped her hands. “I shall spend all my winnings at Galeries Lafayette. Oh, I am so looking forward to Paris.”

“What are you most looking forward to?” asked Arlene. “Catching up with an old friend,” Penny said.

“Who’s that?” asked Archie, jumping on the suggestion. “You haven’t mentioned any old friends in Paris to me. Who are you planning to catch up with?”

When Penny didn’t answer but merely continued to smile a distant smile as the racing results scrolled down the screen, Archie and Arlene both assumed she hadn’t heard the question.“Give me your hearing aids now,” Arlene told the sisters, holding out a palm. “You both need new batteries before we go to France.”

Penny happily handed hers over. From time to time, she quite liked being without her hearing aids. She could go inside her head and tune into her thoughts far more easily without them whistling in her ear. Now, momentarily almost completely deaf, she buried her nose in the catalogue for Stéphane’s auction which Archie had brought along to show them. Archie had thought, rightly, that the sisters would be interested in Stéphane’s new corporate mug shot but that wasn’t the only thing Penny wanted to see. The emerald ring she had spotted online warranted a full catalogue page to itself. A single line on the ring’s provenance confirmed Penny’s suspicions.

Then the racing was finished and, on the television, a film was about to begin. It was the 1945 version of Blithe Spirit.

“It’s your favourite, Auntie Penny,” Archie observed, extra loud.

Chapter Eleven

Purgatory

Otherwise known as St. Mary’s School for Girls.

19TH NOVEMBER 1940

Dear Josie-Jo,

How is my favourite Wren? Thank you so much for the photograph of you in your uniform. I am awfully proud to have a sister in the navy, though I see what you mean about the floppy-looking hat. Hopefully it won’t be too long before you’re made Petty Officer and you can have that natty tricorn.

I am dying of boredom here at St. Mary’s, though there was some excitement last week. I was on fire watch on the school roof when the dreaded Luftwaffe flew over on their way to bomb Coventry. Trudy Sargeant, who can’t tell a Spitfire from a seagull, thought they were our boys and actually waved them on their way! You can imagine how much stick she’s been getting this weekend.

Anyway St. Mary’s was spared—as usual. Doesn’t seem to matter how hard I pray for a bomb on the biology lab—but the girls at Wroxall Abbey woke up to find an unexploded parachute mine in the middle of their lacrosse court. Bad news for The Jolly Girls, whose away match against them was cancelled. Bad news for us too, since old Miss Bull has decreed that we must now have a fire drill before breakfast every morning. She said that while it’s unlikely that Herr Hitler would ever command a direct attack on St. Mary’s School for Girls, the incident at Wroxall Abbey was a timely reminder that a Luftwaffe pilot might offload unused ordnance anywhere on his way back to Germany.I

'm in the upper dorm now so of course my fire escape is down a rope into the courtyard—you must remember that. It’s quite exciting actually. I’ve got my technique down pat. Not that Old Bull is impressed. This morning she said to me, in front of the whole school, “There’s no need to look quite so pleased with yourself, Penelope Williamson. You’re not in training to be a commando.

”Oh, how I wish I were! How envious I am of the young men who are off to be trained for the new Special Service Brigade. I read about it in The Times. Did you? I can’t believe I have to pretend to be interested in the womanly arts for another two terms before I can bid goodbye to this old dump. The minute I am old enough, I’m going to follow you into the services, though it probably won’t be the Wrens. Judy Farmer-Jones went to enlist last week and was told they’re only recruiting catering staff right now. I do not want to spend my war serving pink gins to old admirals!Enough about me. You’ve got awfully important war work to be getting on with, no doubt. Oh, how I envy you, my favourite girl in blue.

Toujours gai!

With kisses from your Perfect P.

P.S. 21/11/40 Your letter arrived this morning, before I had time to send mine. I can hardly believe the news about Connie. I am so sorry, Josie-Jo. I know she was your very best friend. A little sister hardly makes up for it, I’m sure, but I will always be here for you. PP

A whole fourteen months later, in January 1942, the moment of Penny’s liberation arrived.

She was sitting at the breakfast table with her mother and George when she opened her invitation to an interview for the FANY—the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry. When her face was suddenly bright with joy, George and Ma thought she must be reading news of her father, whose regiment was again overseas.

“It’s the best news in the world!”

“No,” said Cecily, when she read the short letter herself.

“Absolutely not. I will not have both my daughters in uniform. I simply cannot allow it. Penelope, you are needed here at home.”

“No, she isn’t,” said George. “You said the other day she’s more of a hindrance than a help around the house.”

Cecily did not bother to contradict her son but was still adamant that Penny would not be going to London to join the FANY and thence find herself sent goodness only knew where.

“Why on earth do you want to go to war?” Cecily asked.

“I won’t be going to war. In all likelihood, I’ll be stuck in an office like Josephine. But I do want to do my bit. You did your bit, Ma, in the Great War. If you hadn’t signed up to drive an ambulance, you might never have met Pa. And then what would have happened?”

“I might have met a sensible man and had two sensible daughters who I could rely upon in my old age. Why can’t you be happy in the Voluntary Service with me?”

“Because I can’t spend a worldwide war making cups of tea! You know if Pa were here he’d say I should join the FANY.”

“He probably would,” George agreed.

“Well, he isn’t here. Oh!” Cecily exclaimed. “What have I done to deserve this?”

In the end, rather than put up with Penny’s pleading and pouting, Cecily said she would think about it. That evening, she gave Penny her grudging permission to attend the interview.

“I’m going to join the FANY,” Penny told Sheppy the dog. “It’s so exciting.”Sheppy greeted the news with an extravagant, tongue-curling yawn.

UNLIKE HER SISTER, who had practically sleep-walked into the Wrens, Penny prepared well for her FANY interview, determined to wow the recruitment board into giving her a position of responsibility from the start.

She’d heard that the FANY were keen to recruit a “certain kind of girl”: the serious kind; practical and efficient. To that end, Penny made sure she looked suitably serious, practical, and efficient for her first meeting at FANY headquarters. She wore no make-up—she had no make-up—and made sure her nails were short and scrubbed. They were always short. They weren’t always scrubbed.

On the train down to London, Penny read the book she had bought with her birthday money. It was martial arts expert Major W.E. Fairbairn’s newly-published Self-Defence for Women and Girls. Mr. Clark, who ran the bookshop, was most surprised when Penny put in her order.

“But I’ve been saving you this new Agatha Christie,” he said. “What do you want to read about self-defence for?”

“Mr. Clark,” said Penny. “We are at war. All over Europe, women are finding themselves face-to-face with the enemy in the most terrifying of circumstances. Every woman should know how to defend her own honour.”

Mr. Clark nodded thoughtfully and made a note to order three further copies for the shop and one for his daughter.

When her W.E. Fairbairn arrived, Penny took the book straight up to her bedroom and pored over the photographs, in which a middle-aged man in a suit and an immaculately groomed young woman in a puff-sleeved tea-dress demonstrated a variety of strangleholds. The book warned against trying out the defensive moves described therein on one’s friends but George—now thirteen—was only too happy to play the evil attacker so Penny could practise escaping various methods of restraint. He pointed out when she demurred that he definitely wasn’t her friend.“Though I suppose you’re alright for a sister,” he admitted when she got him in a headlock.

It was all good fun until Penny gave George a black eye—a proper shiner—while practising her umbrella drill. “The umbrella,” wrote Major Fairbairn. “Is an ideal weapon for the purpose of defence . . .”

So it is, thought Penny as George rolled on the floor.

Luckily, George was not too badly wounded and he was prepared to forgive Penny everything in exchange for a whole month’s sweetie rations

.“Or I tell Ma I didn’t fall out of a tree.”

Harry and Larry, the ten-year-old twin evacuees from Coventry that Cecily had taken in (much to Mrs. Glover’s chagrin), were watching as George and Penelope negotiated.“

You’d better save some of next month’s ration to buy their silence too,” George warned her.

ONCE IN LONDON, Penny alighted the train and marched across the platform with purpose; head up and shoulders back. It was very important to look as though one knew where one was going in a city this size, where all sorts of terrible people might be waiting to take advantage of a young woman travelling alone. Penny managed to brush off the attentions of several people who wanted to help with her case—“Or steal it, more likely!”—but her veneer of invincibility was somewhat punctured when she realised she had left the station via the wrong exit and was heading north instead of south, adding half an hour to her journey.

Thus she arrived at FANY headquarters, in a requisitioned vicarage just south of Hyde Park, feeling a little flustered. In the waiting room, she surreptitiously eyed the other girls. They’d all got the memo about looking sensible. Too sensible. They didn’t look as if they would be any fun at all. As she waited to be summoned, Penny brushed up on her W.E. Fairbairn. She looked closely at the photographs of the gutsy young woman in puffed sleeves dealing with a seated assault in which her besuited attacker placed an unwanted hand on her knee. It was described as “A defence against wandering hands.”“Catch hold of the hand with your right hand . . . Although it is essential that the initial hold of the offending hand should be as near as possible to that shown, you should not have any difficulty in obtaining it, as the person concerned will most likely be under the impression that you are simply returning his caress . . .”

Unconsciously, Penny mimed the steps, which earned her a few funny looks from the other candidates. In response, Penny waved the book.

“Vital information for the modern girl.”

FINALLY, PENNY WAS called to the interview room, where two magnificent middle-aged women, resplendent in the FANY’s khaki uniform, awaited her. They took it in turns to ask the questions Penny had expected. Which subjects had she liked best at school? Did she play any sports? Did she know the history of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry?

“It is the oldest and most venerable of the women’s services,” Penny said. “First conceived in 1907 as a cavalry of nurses to support front line troops. Original recruits were expected to be accomplished horsewomen. As am I,” she added. If always coming bottom of the league table at Pony Club counted.Both her interviewers nodded with satisfaction. “Can you drive?” they asked.“I learned in my father’s Bugatti.”

“Can you lay a fire?”

“Had to brush up on my skills after our housemaid ran off with the gardener’s boy. Took ages to find a replacement.”

“Do you ever do the Times cryptic crossword?” the younger interviewer asked.

“Well, yes,” said Penny.

“And do you usually manage to complete it?”

“Always.”

“Wonderful.” The more senior FANY slapped her hands on her knees and stood up. “You’re exactly the sort of girl we’re looking for.”

SUCH JUBLIATION WHEN confirmation of Penny’s acceptance into the FANY arrived a few days later! She had just a week at home with Ma, George, Mrs. Glover, and the evacuees, before she was expected back at FANY HQ to embark upon basic training. The night before she left, Mrs. Glover made a special cake, using everybody’s sugar rations. They all agreed it was the best thing that had ever come out of the kitchen on Mrs. Glover’s watch, though perhaps that was because, two and a half years into the war, everyone’s standards were very much lower.

After supper, George and the evacuees invited Penny to try her self- defence skills on them one more time. As she fended the boys off with sofa cushions, she warned them that by the time she had completed her FANY training, she would be able to take down a Messerschmidt with a catapult and finish the pilot off with her bare hands. The boys were delighted. They made solemn vows to protect the home front while Penny was off fighting the Nazis.

THE NEXT DAY, Penny returned to London and was thence transported to a large country house in the Home Counties to be put through her paces. She was so excited but alas, basic training turned out to be awfully dull. There were endless, pointless drills and lots and lots of housework. Every day started with the clearing of numerous fireplaces.

“I feel like Cinderella,” Penny complained to another trainee, who simpered and said she hoped their princes would turn up soon. Most of Penny’s fellow new FANYs were sensible but wet. There were definitely no opportunities for Penny to try out her W.E. Fairbairn on a willing and worthy adversary.

At the end of the fortnight of grate-scraping and square-bashing, Penny returned to FANY HQ in London to await further instructions. She was billeted in a requisitioned house near to FANY headquarters, where she shared a room with three other girls. Every surface was always festooned with drying stockings, that were inevitably still slightly damp when you put them on again, and the air was thick with scent.

One of the girls, Pamela, was a little older than the rest at twenty-two. She had joined the FANY in a rush of blood to the head after a broken engagement, though she told the girls they should not feel sorry for her for having lost her man at a time when they were in short supply. She’d been the one to break it off.“I couldn’t have spent the rest of my life with him. You’ve got to be sexually compatible with the man you marry,” she said. She underlined the importance of her pronouncement by taking another drag from Penny’s cigarette and exhaling a long plume of smoke out through the window. She didn’t give the cigarette back but Penny didn’t mind. She hung on Pamela’s every word. “Besides,” Pamela continued. “I heard that shortly after I called the engagement off, he was seen in the company of a submariner at The Pink Sink.”

Pamela’s audience gasped at the mention of the notorious gay club beneath The Ritz Hotel, where it was said the men took it in turns to take the ladies’ part on the dance floor.

Penny had quickly developed a huge girl crush on Pamela, who was the big sister she wished she had, instead of boring old Josephine, whose letters lately were only ever about weather and books. Pamela was the very essence of toujours gai, so Penny was delighted when she chose her to accompany her on a double date. Pamela’s beau Ginger had four tickets to see Blithe Spirit. Would Penny like to come along as company for his friend?

“He’s really nice,” Pamela assured her.

“Have you met him?”

“Well no, but I’m sure he’s a perfectly decent sort.”

“Then why not?”

Penny didn’t tell Pamela that it would be her first proper date, assuming sitting in the stairwell with Gilbert Declerc didn’t count.

DRESSED IN THEIR brand-new FANY uniforms—made-to-measure if a little bit dowdy when compared to the Wrens’ chic navy blue—Penny and Pamela met Ginger and his friend in the American Bar of The Savoy. Ginger’s friend was called Alfred and Penny was relieved that on first impression he seemed like a nice enough chap. He had a friendly round face and thick brown hair. He was tall too, which was good. He was an army man, on a forty-eight from training on Salisbury Plain. Penny was glad to find out more about the place where her father had been sent ahead of his going overseas.

At The Savoy, Alfred and Ginger bought the girls two pink gins apiece, but Penny was careful to make sure she didn’t drink all of the second one. The first made her feel sophisticated and warm inside. She suspected the second might unravel those happy feelings, or, worse, turn her into a fast girl. While Alfred wasn’t looking, she tipped half of it into a plant pot.

Since the theatre was not far from the hotel, when the time came to leave they decided to walk. Ginger and Pamela had been stepping out for a while, so she let him put his arm around her waist. Alfred lent Penny his arm. She didn’t need his support but she took it all the same. It brought her close enough to smell his aftershave. Old Spice. That made her feel much giddier than one and a half pink gins.

Penny sneaked a glance at Alfred’s profile. Could she love him? He was no James Stewart but perhaps he’d be her romantic hero yet.

As they walked, it began to drizzle and Ginger and Pamela charged ahead to save Pamela’s hair. Meanwhile Penny tried to impress Alfred with her air of toujours gai. It seemed to be working. Alfred took off his coat and draped it around Penny’s shoulders in a thrillingly gallant gesture. What came next was somewhat less so . . .

“Are you a virgin, Penny?” Alfred asked as they waited to cross the Strand.

Penny was too shocked to tell him it was none of his business. Instead, she meekly said, “Why, yes. Yes, of course I am,” then tried to pretend he hadn’t asked. Alas he wasn’t going to leave it at that.

“So no one ever tried it on with you?” he persisted. “No one ever touched you under that nice khaki skirt?”

“I . . . er . . .”

“I bet you’d be a right little goer once someone got you started . . .”

Penny was exceedingly grateful to see Pamela reappear up ahead, waving programmes.

“Show starts in three minutes,” she yelled.

INSIDE THE THEATRE, they sat right in the middle of the stalls. Even before the house lights were dimmed, Penny was extremely aware of Alfred’s arm pressing against hers and she wasn’t at all certain she liked it.

She’d heard such wonderful things about Blithe Spirit, and had been terribly excited to see it, but the presence of Alfred at her side made it very hard to concentrate. Rather than listening to Coward’s perfect lines, she found herself going over and over the awful conversation they’d had on the walk from The Savoy. There was nothing witty about it and she wished she had not brushed it off so easily. She should have dropped Alfred’s arm and slapped him. She was sure that was what Pamela would have done. Pamela would never have accepted such nonsense.

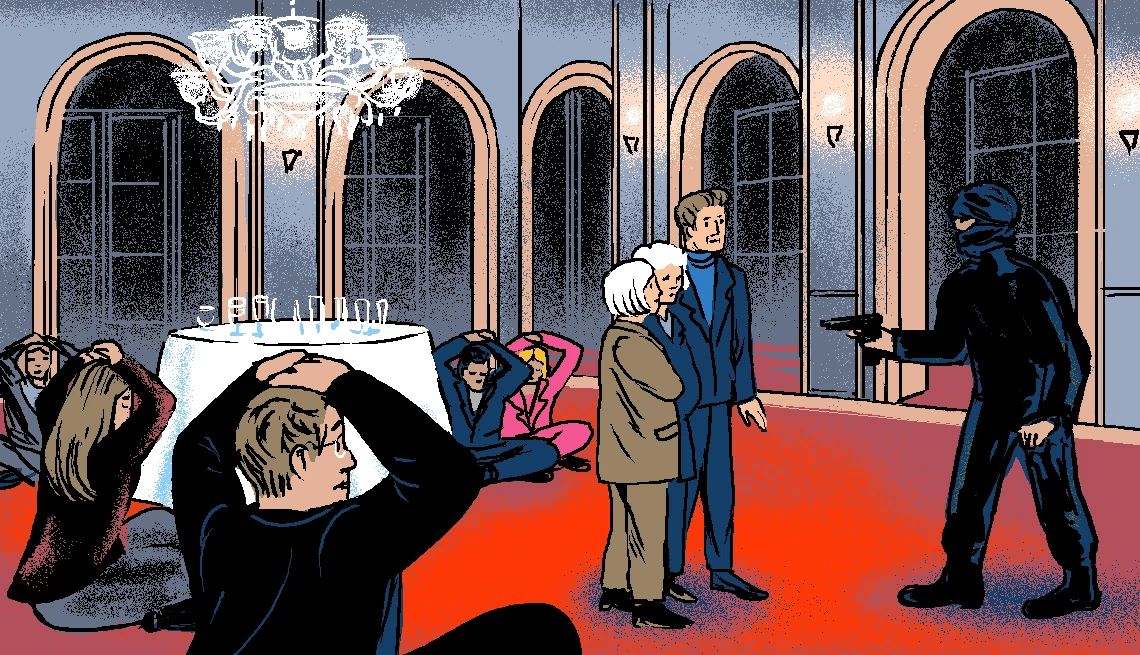

While the audience all around her laughed their heads off at the action on stage, Penny’s expression hardened and her mouth settled into a thin tight line that her siblings would have recognised as a warning sign. All the time, Alfred was edging further and further into her space, quite oblivious to her discomfort. His arm was soon taking up all their shared armrest. It wasn’t long before his thigh was pressing against hers too. She tried to evade him, moving as far towards Pamela as she could. Pamela didn’t notice. She was too busy necking with Ginger. Still Alfred continued his offensive. Then he let his hand fall into Penny’s lap and gripped the top of her thigh so hard she was sure he must be leaving bruises.

As she recovered from the initial shock, Penny found herself feeling a strange mixture of emotions. She was horrified that Alfred had made such an unacceptable advance and yet she was also thrilled. She was thrilled that at last she was going to be able to put into action one of the most interesting moves in Major W.E. Fairbairn’s Self-Defence for Women and Girls. This was quite literally a textbook situation.

Penny remembered the instructions under “A defence against wandering hands” almost word for word; how her assailant would not have the faintest clue what was going on because he would assume, when she took his hand in hers, wrapping her thumb and fingers tightly around his palm, that she was merely returning his expression of interest.

Poor Alfred. He had no idea what was coming.

Breathing slowly to keep her heart from racing, Penny waited for her moment. She would have just one chance. She had to get it right.

Keep calm, keep calm, she told herself.

When the audience erupted into laughter at a particularly pithy line on stage, she made her strike. With all her might, Penny pulled Alfred’s rogue hand across her body with a jerk, causing him to suddenly double forwards and—in a development Penny hadn’t planned for—crack his nose on the back of the seat in front of him. Sitting up, stunned and with blood pouring from both his nostrils, Alfred let out a roar of outrage followed by a long stream of expletives that had everyone within a fifty-seat radius shushing.

While Alfred railed, Penny quickly got up and left, stepping on numerous feet as she made her escape. She managed to keep relatively calm until she got to the lobby, then she burst from the theatre onto the blackout dark street and ran all the way back to the FANY boarding house, with her hair flying and her gas mask bumping against her hip.

What had she done? What had she done! She was astonished at how well the move had worked. Good old Major Fairbairn.As Penny reached the boarding house, an air raid siren rent the air. The other girls in the house, many of whom were already tucked up in bed, quickly made their way down to the shelter, but Penny lingered outside the building, taking her time, waiting until she saw the deathly shadows of the Luftwaffe planes overhead. She felt exhilarated, liberated, strong. Tonight she was an Amazon.

“Come on, Hitler,” she shouted at the sky. “Come on, all you Nazi bastards. I’m ready!”

Chapter Twelve

London, 2022

Archie stayed overnight in the guest room in South Kensington to be certain that the journey to France would go without a hitch. They were to be taking the 12:24 Eurostar, which, by Archie’s reckoning, meant they needed to leave the house at ten at the latest to ensure they had enough time to get through security and passport control. Archie booked a taxi and tried not to panic when, at nine o’clock, the sisters were still eating their breakfast in a frustratingly leisurely way.

He tried to calm his rising fear that the sisters would somehow transpire to miss the train by leaving them to it and absenting himself to the sitting room to go through a box of letters he’d brought down from the attic.

Over the years, Archie had spent many hours in the attic at Penny and Josephine’s house, sifting through boxes of letters, telegrams, ration books, and photographs of goodness only knew who—the sisters certainly didn’t remember. In one box he’d found a diary dated 1817, belonging to some long-forgotten Williamson ancestor. Unfortunately, the faded handwriting revealed nothing particularly interesting, unless you were fascinated by livestock prices in the early nineteenth century. There were still at least a dozen more boxes to catalogue however and any one of them might contain something really exciting. Something for the history books.

Perhaps it was because Archie was the only child of an only child on his father’s side that he felt such a responsibility to record all the memories that might otherwise be lost. Though it wasn’t just on the Williamson side that Archie had appointed himself family historian. Recently he’d started to trace his mother’s line too.

Archie’s mother Miranda came from a very different background to his father. Charles Williamson was an old Etonian who’d grown up cocooned by layers of unimaginable privilege. Archie’s mother Miranda was a grammar school girl from Cirencester who’d won a scholarship to Oxford. They met while they were both working in the city. Charles was instantly captivated by Miranda. She was five years his senior and seemed so sophisticated and worldly-wise. In return Miranda loved Charles’ confidence and his upper-class polish, which soon began to rub off on her. No one meeting Miranda Williamson for the first time nowadays would guess she hadn’t been born to the pony club life.

In fact Miranda’s parents Tom and Clara Smith had both worked at a biscuit factory. Archie had fond memories of visiting them in their ugly seventies house where they let him eat his tea from a tray on his lap in front of the television, something that only happened at home if he was off school with tonsillitis.

With fond thoughts of those happy times, Archie had initially applied the same enthusiasm to tracing the Smith family line as he had the Williamson but there was so much less to work with. Even when Archie was old enough to hear about it—warts and all—Tom and Clara had never talked much about the past. Whenever Archie visited, they were much more keen to hear about his plans for the future.

“Any sign of a girlfriend yet?” Clara would ask. “The girl who gets her hooks into you is going to be very lucky.”

Tom and Clara had died before Archie felt ready to come out.

The Smiths had left behind boxes of papers but there were no distinguished war records, no deeds to great family estates or handwritten letters from long-dead dukes and princes such as were rotting in his paternal great-aunts’ loft. Only gas bills and ten pounds’ worth of premium bond certificates and, poignantly, a pile of birthday and Christmas cards hand- drawn by Archie as a child. The 1970s house belonged to the council and was quickly passed to a new family. There wasn’t even any old furniture that might have a story behind it. Tom and Clara preferred new, not understanding how the late Tory Minister Alan Clark’s snide comment regarding his colleague Michael Heseltine’s having bought his own furniture could possibly be seen as an insult. Why wouldn’t you buy new if you could afford to?

Yes, the Smith family history was all very boring. Until Archie’s mother dropped a bombshell.

Over Easter lunch Miranda had told Archie that, on her death bed, his grandmother Clara had muttered something about Miranda’s parentage being “not exactly as described.” What could it mean other than that the identity of her father was in doubt?

“I think he might have been a GI,” Miranda confided. “There were thousands of American servicemen down the road on the airbase at Fairford. Your grandma used to go to dances there.”

The more Archie thought about it, the more it seemed a distinct possibility that his mother was not Tom Smith’s child. Miranda didn’t look like any of her siblings. She was different in personality and in her interests too. She was the odd one out long before she married well and “got above herself.” But how could she find out for sure?

Archie already subscribed to a genealogy website on which people raved about DNA testing. They’d found cousins, half-brothers, and even full sisters that way. Some of them had discovered they were not in fact related to their own fathers, which must have been hard. Archie had no fear of that. His “difficult” feet were one hundred per cent inherited from Charles Williamson.

Confident that there would be no nasty shocks regarding his own parentage, Archie ordered one of those DNA kits and—putting aside his absolute horror of spitting—filled a test-tube with saliva which he duly sent away to be analysed. He couldn’t wait to get the results.

From THE EXCITEMENTS by CJ Wray. Copyright © 2024 by C J Wray. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

You Might Also Like

Meet ‘Excitements’ Author CJ Wray

This long-time romance writer was inspired to switch genres by real-life sisters still having adventures in their 90s

Free: James Patterson's Novella ‘Chase’

When a man falls to his death, it looks like a suicide, but Detective Bennett finds evidence suggesting otherwise

More Free Books Online

Check out our growing library of gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety

More Members Only Access

Enjoy special content just for AARP members, including full-length films and books, AARP Smart Guides, celebrity Q&As, quizzes, tutorials and classes

Recommended for You