AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Ten

SALLY PENGELLY WAS WAITING for Matthew in the mortuary, gowned and booted.

‘Thanks for doing this so speedily at a weekend.’ Matthew knew she had a family: a husband who was head teacher of a village primary school, and at least three children. He and Jonathan had been invited once to a barbecue at their home, a rambling place with a garden and orchard, a paddock with ponies. There had been a lot of children there, all running wild, and he hadn’t quite worked out which of them belonged to Sally. It had been a chaotic and good-humoured evening. Jonathan had loved it; Matthew not quite so much. There had been insects and they’d had to sit on the grass.

‘This suits me better than tomorrow morning,’ she said. ‘Finn’s got running club and Jo’s at youth orchestra. Freddie says the surf’s looking good, so he has to be at Croyde. Bloody kids rule our lives.’ A pause. ‘And we didn’t want to leave Dr Yeo at the locus longer than necessary. That poor young woman, with her father’s dead body on her doorstep. In her workplace.’

Matthew nodded.

‘You don’t need to stay throughout.’ Sally was already focused on the body on the stainless-steel table. The mortuary technician moved quietly and efficiently beside her. ‘Cause of death is pretty clear and, of course, we have an ID.’ She looked back at Matthew. ‘You’ve had quite a day. You’ll be glad to be home. So, let’s get on with it, shall we?’

Her assistant started cutting away Nigel’s clothes and Sally provided the running commentary:

‘In the trouser pockets, we have a handkerchief and two sets of house keys. No car keys.’ She turned again to Matthew, a question.

‘They’d been left in his car,’ Matthew said. He wondered if that was significant. Had Yeo been distracted when he arrived? Did he trust the Westacombe residents not to steal the vehicle? But wasn’t locking a car automatic? Matthew kept a running log throughout an investigation, and now he opened the blue, hardback notebook and wrote a reminder to check with Eve if her father usually left his vehicle unlocked when he was at the farm.

Sally was still speaking. ‘The cause of death is a stab wound to the neck, and severing of the artery and critical nerves controlling cardiac and brain function. Bleeding will have been brisk, at least until the blood pressure dropped, and we noted the pulsatile nature of the spatter on the workshop wall.’

Matthew closed his eyes for a moment and pictured the crime scene, the blood. It was hard to imagine that one man could produce so much.

Sally continued. ‘The murder weapon was this piece of glass. The axial strength meant that it didn’t shatter, though there is evidence of deformation where it hit the bone.’ She turned to Matthew. ‘Really, this is all as we thought at the locus.’

‘I did wonder,’ he said, ‘if the glass was window dressing, there for effect.’

She shook her head. ‘Glass can be remarkably strong. I did part of my training in Aberdeen. Plenty of glassings in pub brawls there.’ She paused for a moment. ‘Go home to your husband. I’ll get my report to you as soon as I can, and I’ll be in touch immediately if I come across anything unusual.’

For a moment he hesitated. Duty had become a habit, almost reassuring, an excuse to avoid the personal. But Sally was right. There was nothing more for him to do here.

***

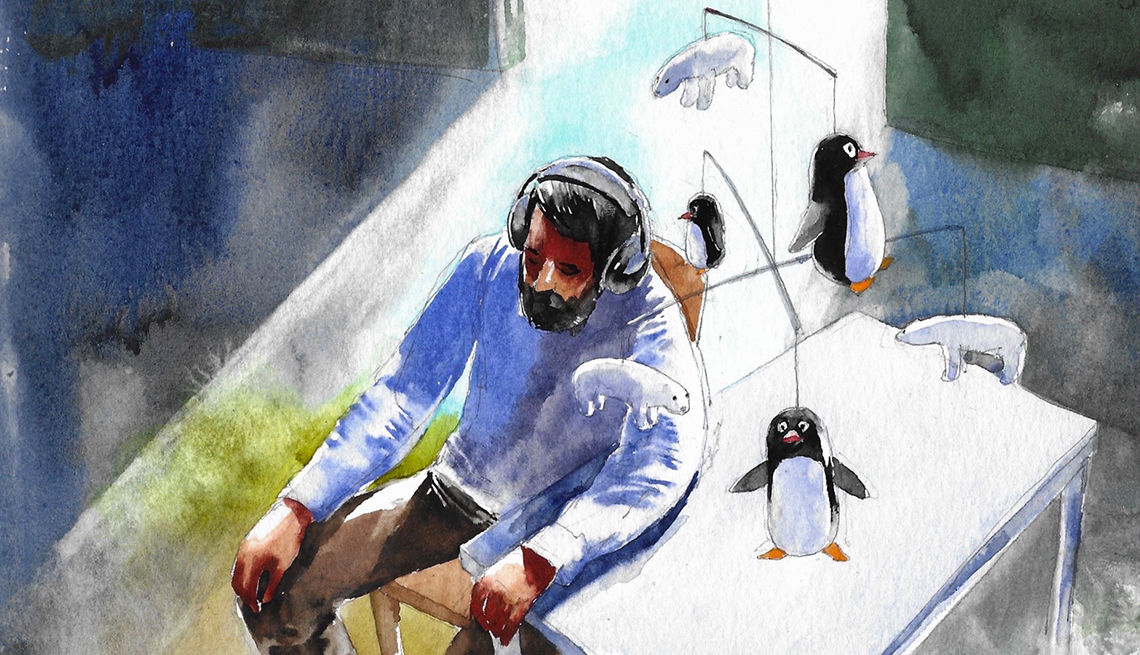

It was dark when he got home, but Jonathan was still in the kitchen, music playing. Something cool and bluesy that Matthew didn’t recognize. Jonathan was at the sink, peeling vegetables. He turned and took Matthew briefly into his arms. No words until they’d separated.

‘I met Eve today. She told me what had happened.’

‘Will she hold it together, do you think?’ Matthew took a seat at the long table.

‘Yeah, in the end. But to lose her father so soon after her mother ...’ Jonathan paused. ‘I invited her to come and stay. I don’t think she should be on her own there, so close to where her father was killed.’

Matthew looked up sharply. For a moment he couldn’t quite believe what Jonathan had said. ‘She’s a witness to a murder. A potential suspect. You can’t see that it would be impossible to have her here?’

‘You really believe that Eve could have killed her father?’ Jonathan’s face was set, stubborn. ‘And that protocol is more important than kindness?’

‘The rules matter!’ Matthew was aware of his voice rising, that he was almost shouting, and made an effort to remain calm, reasonable. ‘Sometimes they’re the only thing between us and chaos.’

They stood staring at each other in silence. Matthew broke it first. He nodded towards the sink. ‘I’m sorry but I’m really not that hungry.’

‘This isn’t for tonight,’ Jonathan said. ‘I’m getting prepped for tomorrow. Your mother’s grand lunch.’ His voice was brighter. In his mind, at least, the tension between them was over; he was clearly looking forward to the occasion. He put his arm around Matthew and kissed him lightly. That was Jonathan all over. He hated confrontation and never saw the point of letting an argument drag on. He thought that a moment of tenderness could make everything better. Matthew felt the old dread settle like a headache, but said nothing.

Chapter Eleven

ROSS AND MEL HAD A ROUTINE for Sundays if neither of them was working. Sometimes she had to go in; she was manager of an old folks’ home and took her job seriously. It wasn’t fair, she said, for the care staff to work shifts if she didn’t take her turn. She’d started working there when she was sixteen, fitting it in around taking the care qualification at the FE college on the edge of the town. They’d already been going out then. Childhood sweethearts. She’d worked her way up from care assistant, from wearing the ugly pink tabards to her own clothes. Always smart. Ross hadn’t liked to think of her wiping the old men’s bums, had been a bit embarrassed about her job, but he was proud of her now.

Mel and Ross had met at school. She had always been the prettiest in the class and not just good-looking, but easy-going and even-tempered too. Not one of the stuck-up girls who thought it was clever to bad mouth or tease. Not pushy or overly academic either. Despite her looks, he had never found her intimidating. They’d first started going out when they were fifteen and had been married in their early twenties.

Ross’s parents had been through hard times, and he didn’t want that for himself. He’d already mapped out his life before Mel walked down the aisle to be his wife. Security was important. He and Mel had bought their own home while their friends were still renting or spending their cash on travel and flash cars, instead of investing in their future. Ross had grand plans for his future: promotion, a bigger house. That would be the time for fancy holidays.

Sunday morning started with the Park Run. Ross liked his sport. In the winter it was rugby; Joe Oldham had introduced him to the club when Ross was still a boy, and the superintendent came along to cheer at most of the important matches. Though he usually retired to the bar at half-time. This time of year, Ross still wanted to keep fit. He had a horror of ending up like his dad: flabby, his belly hanging over his belt, taking no pride in his appearance.

Mel was a good runner too and went out with her mates some mornings, coming back glowing, laughing just with the pleasure of the exercise. Ross thought that was when he loved her most. She was a credit to him. He’d tried to persuade Jen Rafferty along to the Park Run, but she’d looked at him as if he was crazy. Are you joking? On a Sunday morning? Ross wished Jen would take him more seriously — everything was a joke to her — because he only had her best interests at heart. At her age, she could use more exercise and it wouldn’t hurt if she cut down on the booze. Not that he said anything about that. Jen had a way with words that made you wary, that could cut into you like a knife. With one sentence she could slice away his confidence and his self-belief. If he’d known her at school, she’d have been one of the girls he’d have avoided like the plague.

After the run, Mel always did a cooked breakfast. It was the high point of his week. Some of their running mates went out for brunch in a cafe close to the park, but Ross could never see the point. It all cost money and, anyway, the food wasn’t great; there was nowhere decent to eat in Barnstaple. And Mel was a great cook. Today, it was scrambled eggs and smoked salmon on sourdough toast. Afterwards, she made a pot of real coffee — on weekdays, they made do with instant — and they took their mugs out into the garden. He sat with his face to the sun and thought this was all he’d ever wanted: to be a good cop and a good husband. Maybe a good father when the time was right. Mel got up from her deckchair and began to pull a few weeds from the flower bed next to the path.

He looked at his watch. ‘I’ve got to go in to the station. We’re working on that murder out at Westacombe and the boss has decided he’s got something important on at home. Who knows what Jen will be up to?’ He rolled his eyes. ‘One of us has got to be there.’

She was still crouched, and turned to face him, her eyes screwed up against the sun.

‘No worries,’ she said. ‘I’ll do the washing-up, shall I?’

He thought he caught an edge to her voice, a touch of sarcasm. ‘Is that okay?’ He wouldn’t want to upset her for the world.

‘Yeah.’ She stood up and smiled. ‘I know how important your work is.’

There was a moment of relief. He should have known she wouldn’t have a go at him. He was overreacting. ‘I won’t be back until late-ish. I’ve got to take a witness statement out at Instow, then there’ll be the briefing.’

‘That’s all right. I might go out for a drink with the girls.’

Again, he thought he caught an undercurrent of resentment, but when he looked at her face, she was still smiling.

***

The police station was like a sauna; the sun was streaming through windows that had never been opened and, of course, there was no air con. Ross looked again at the list of the calls Nigel Yeo had made in the previous week. Besides those to Eve and to Lauren Miller, everything seemed work-related. He must have been a sad bastard. Not much social life at all. There was a text sent at six o’clock on the evening before his death by Cynthia Prior: Look forward to seeing you later. Nothing else that day. So, Ross thought, any meeting at Westacombe had been arranged previously. Or Nigel had been contacted on his landline. Or he’d turned up on the spur of the moment. That was speculation, of course. Ross had learned from Joe Oldham to be suspicious of speculation, but Matthew Venn thought it was a useful tool. Our job is all about What if? No harm creating a number of scenarios and seeing if the facts fit. The danger comes when you twist the facts to fit the theory.

It was still a bit early to be heading out to Instow, but Ross left the station anyway. He thought he’d call in at the house, surprise Mel. They might go to bed. Sex in the afternoon had always been his favourite, and, somehow, they’d got out of the way of it. Too busy both of them. He was excited, a schoolboy again, planning illicit jaunts with his girlfriend, as he drove through the new executive estate, past the men washing cars and the kids playing out. But when he got there, Mel’s car wasn’t in the drive. Perhaps she’d popped round to her parents’. He rang her, but when she didn’t reply, he decided not to wait. The moment of uncharacteristic spontaneity had passed.

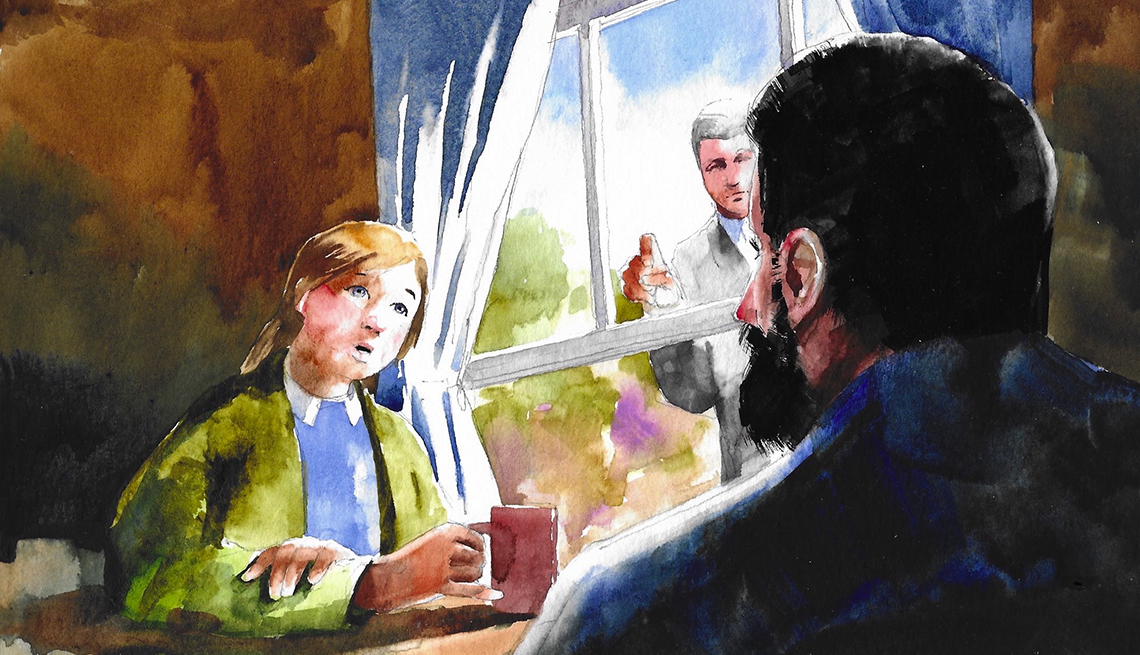

There were more cars heading away from Instow as he drove there than were making their way to the coast. Family Sunday afternoons were a time of preparation for the week ahead: homework, hair wash, the ironing of school uniform. At least, that was how it had been when he was a boy. And this wasn’t yet prime grockle season. A few people were still in the Sandpiper, but they were lingering over coffee, relaxed. Ross had never been in here. It wasn’t his sort of place. Most of the customers were his parents’ age. A young woman was drying glasses at the counter. Blonde hair. A white blouse, the cotton thin enough that he could see her bra. She moved out to clear a table and he saw she was wearing skinny jeans and Converse sandshoes.

‘Janey Mackenzie?’

‘Yes.’ She seemed to see him for the first time. ‘Oh, you must be the detective. Dad said someone would be coming.’

‘Yes, I need to talk to you about Friday night.’

She was still carrying a tray. ‘Just a minute. I need to get rid of this.’ She disappeared into the kitchen and returned soon after with a middle-aged man. ‘This is my dad. He’ll cover while I talk to you. Do you mind if we walk on the beach? I’ve been stuck in all day.’

She looked at him, waiting for his agreement.

‘Of course, if that’s what you’d prefer.’ She gave him a smile and he followed her out of the door.

Outside, it was early afternoon, even hotter, and despite the cars heading back to Barnstaple, the beach was still heaving. Kids were running in and out of the water, splashing and screaming. Janey took off her shoes and made her way to the sea’s edge, then walked away from the worst of the crowd towards the far end of the beach. He wasn’t sure what to do. He was dressed for work, not for the shore. In the end he followed her, but stayed on the dry sand, just about close enough to speak to her without shouting.

‘Friday night you were at a party with Wesley Curnow?’

‘Yeah. Not exactly my idea of fun.’ She pulled a face that made him smile.

‘Why did you go then?’ Ross wasn’t sure where the question had come from. How could this be relevant to the investigation? But something about her intrigued him. He’d expected her to be confident, arrogant even. She’d been to a fancy university, was good-looking in a way that would catch attention wherever she went, and she had a mother who was a minor celebrity. Ross was always suspicious of people who were better educated than him. He sensed they were judging him. Janey didn’t give that impression, though. There was something of the little girl about her: nervy but precocious. He thought she’d say the first thing that came into her head, no filter, no matter how that might seem to the listener.

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members