AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Sixteen

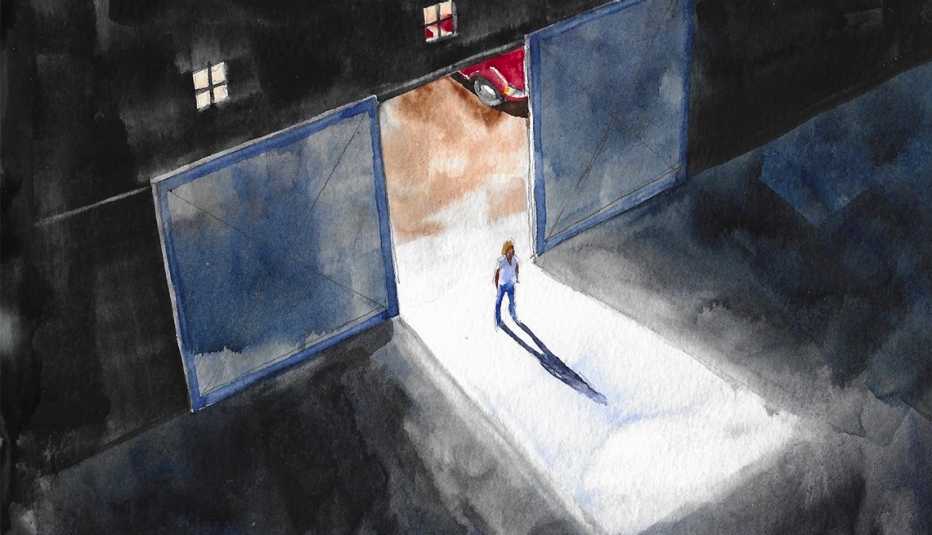

MATTHEW LEFT LAUREN MILLER’S HOUSE IN Appledore and drove back to Barnstaple. Dorothy Venn was waiting for him at her home. Matthew could see her peering through the window of the bungalow where he’d grown up as a child. It had always felt like an old person’s house, even when his parents had been in early middle age. It was as if his mother, at least, had always been anxious, always planning for some disaster, which had never occurred until her son, her only beloved child, had renounced his faith publicly at a meeting of the Brethren and brought shame upon her whole family.

It had been a murder which had brought them together again, a body on a beach and the kidnapping of a woman with a learning disability. Matthew supposed he should be grateful for the resulting awkward reconciliation, but sometimes he thought life had been easier when there’d been no contact. Contact brought responsibility and he could see now in the gaunt, sharp face looking out at him that his mother was getting old. He was the only son and the only person who would care for her.

There was no sign of weakness, however, when she opened the door. ‘I thought you were going to be late.’

He was five minutes earlier than they’d arranged but he said nothing. He opened the car door for her and helped her in. ‘Happy birthday!’

‘It’s only another day. Nothing to make a fuss about.’ ‘Have you been to the meeting?’ He meant the meeting of the Barum Brethren, held in a dusty community hall on the edge of the town. He remembered the smell of rising damp, disinfectant and elderly women. ‘Of course! Brother Anthony gave me a lift and brought me home.’

Of course. The Brethren might have been riven by scandal and corruption, but she’d chosen to maintain her loyalty. Matthew could understand that. It had been hard enough for him to break away as a young man and the community was all that his mother had known. Like him, she’d been born into it.

They drove the rest of the way in silence. She sat with her handbag on her lap, her knees firmly together. She was still in the clothes she would have worn to the meeting: a green skirt and a long-sleeved white blouse. Despite the heat, she had on a green, hand-knitted cardigan. She had removed the hat, something woollen and mushroom-shaped, which seemed to be required dress code at Brethren worship. She spoke first.

‘Where exactly do you live?’

‘In the house close to the shore at Crow Point. Do you remember, we had picnics on the beach there sometimes?’

She nodded and for the first time gave a little smile. ‘Your father loved a picnic.’ A pause. ‘I could never see the point. Sand gets everywhere. But he loved the open air.’

‘You must miss him a lot.’

For a while, Matthew thought he’d overstepped some virtual mark, become too personal, but at last she answered. ‘I do. All the time. If it weren’t for the brothers and sisters, I think the loneliness would kill me.’

The comment took his breath away and a wave of guilt swept over him. He’d thought his mother had stuck with the Brethren out of stubbornness, or because her faith had remained despite the drama surrounding it earlier in the year. But of course, these people were her friends. They’d been there for her when her husband died and when Matthew had stayed away.

They came to the traffic lights in the centre of Braunton. There was already a queue of cars leading to the coast and the lights changed twice before they could get through. A group of bronzed, scantily dressed young women crossed the road in front of them and he sensed his mother’s disapproval, but she didn’t speak. They crawled along the road until the turn-off by the Great Marsh. This was a place for locals; most holidaymakers didn’t realize that it was a way to the beach, to the other end of the long sweep of Saunton Sands. Matthew threw change into the basket at the toll keeper’s cottage, the gate lifted and he drove through. He pulled into their drive and switched off the engine.

‘This would be a bleak sort of place in a gale,’ his mother said. He opened the car door for her and offered her a hand to get out. She stood for a moment looking around her. ‘You’ve made a lovely garden, though.’

‘That’s Jonathan’s work,’ Matthew said. ‘He’s the practical, creative one.’ Again, she took a while to answer.

‘I don’t know about that. You were always creative when you were a boy.’

Matthew smiled. The words felt like a vindication. Of himself as a boy and of the relationship with his husband. Perhaps, after all, this would work out. ‘Come on in. You’ll see he’s a brilliant cook too.’

She sniffed. ‘No need to have gone to any trouble.’

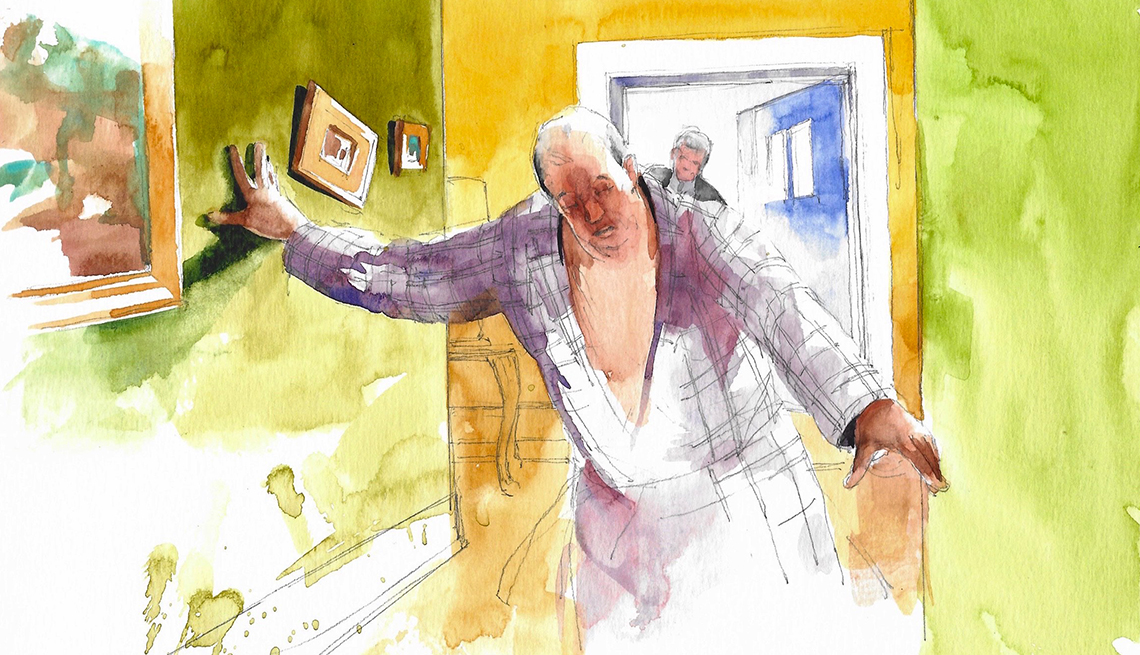

Jonathan had heard the car and was at the door to meet them, arms wide in greeting. ‘Come in! And happy birthday, Mrs Venn!’ He gave Matthew a light kiss on the cheek.

His mother pretended not to notice and was looking round the kitchen. ‘This is very fancy.’

‘We love it,’ Jonathan said.

The table was laid and there were two vases filled with deep red roses from the garden. The window was wide open and the curtains stirred in the breeze. It was as close to eating outside as Jonathan could make it.

Jonathan took off his apron and hung it on the back of the cupboard door. He was wearing black shorts and a black T-shirt with the name of a craft brewery on the front. Dorothy wouldn’t recognize the name. On his feet he wore flip-flops. His toes were wide and flat. Matthew called them hobbits’ feet. A silliness and intimacy he’d allowed himself with no other person. His mother stared at Jonathan for a moment, as curious as if he were a being from another planet.

‘Are you ready to eat?’ Jonathan asked. ‘Or would you like a tour of the house first?’

‘Why don’t we have lunch now?’ Matthew couldn’t bear the idea of showing his mother around the house: another bedroom with two dressing gowns and another bathroom with two toothbrushes. And Jonathan wasn’t the tidiest person. Who knew what might be left out? Matthew wanted to check first. ‘I might be called back to work. We’re in the middle of a murder investigation.’

‘That makes sense.’ Jonathan rolled his eyes at the mention of work, but only Matthew could see. ‘And of course, I have champagne!’

Dorothy still hadn’t spoken. The room with its flowers, the copper pans hanging from a rack on the ceiling and the art on the wall — mostly posters for exhibitions Jonathan had held at the Woodyard — seemed to overwhelm her with its space and its colour. She appeared almost breathless.

Jonathan went to the fridge and pulled out a bottle. Only the supermarket brand, but real champagne all the same. ‘Let’s have this with the starter.’

Matthew expected his mother to refuse. Alcohol wasn’t forbidden by the Brethren and his father had enjoyed a whisky most evenings after work, but Dorothy never participated. More, Matthew suspected, because she enjoyed the martyrdom of denying herself pleasure than through religious conviction. Now she stood in the middle of the room, gripping her handbag, looking around her, and he saw that she was nervous. He’d never known his mother be anything other than confident in her certainty.

‘There’s orange juice if you prefer,’ Jonathan said very gently. She might have been one of his clients at the Woodyard day centre. ‘It’s your day. Whatever makes you happy. Why don’t you sit here with your back to the window, then you’re not squinting into the sun?’ He took her arm and led her to the head of the table.

Matthew watched, moved, as she took her seat. She smiled. At Jonathan, not at him. ‘I might try a glass of champagne,’ she said. ‘I had some at a wedding for the toasts and I did quite enjoy it.’

Jonathan turned, winked at Matthew and opened the bottle.

The phone call came late in the afternoon. Dorothy had complimented Jonathan on the tenderness of the beef, the way the Yorkshire puddings had risen. ‘I was never very good at batter. Not for Yorkshire puddings or pancakes.’ The cake, with its candles and elaborate decoration, had been a huge success. After a lifetime of healthy eating, it seemed to Matthew that his mother actually had a very sweet tooth and she had been persuaded to have a second slice. He and Jonathan had sung happy birthday, Jonathan taking the lead. The whole afternoon had a strange surreal tinge to it. It was hard for Matthew to believe that this woman, who had haunted his life and had been the subject of earnest discussions with his therapist, had become elderly, lonely and powerless. Someone who was willing to compromise in return for kindness and company.

By now she was rather pink and had removed the cardigan. Her handbag had been put under her chair. She looked younger, more relaxed than Matthew could remember. Jonathan had been collecting plates. There were two empty coffee cups on the table. Dorothy had asked for tea and Jonathan had made it for her in a small pot. She’d liked that; she still disapproved of teabags. Matthew had switched off his phone, but he could hear it vibrating in his pocket.

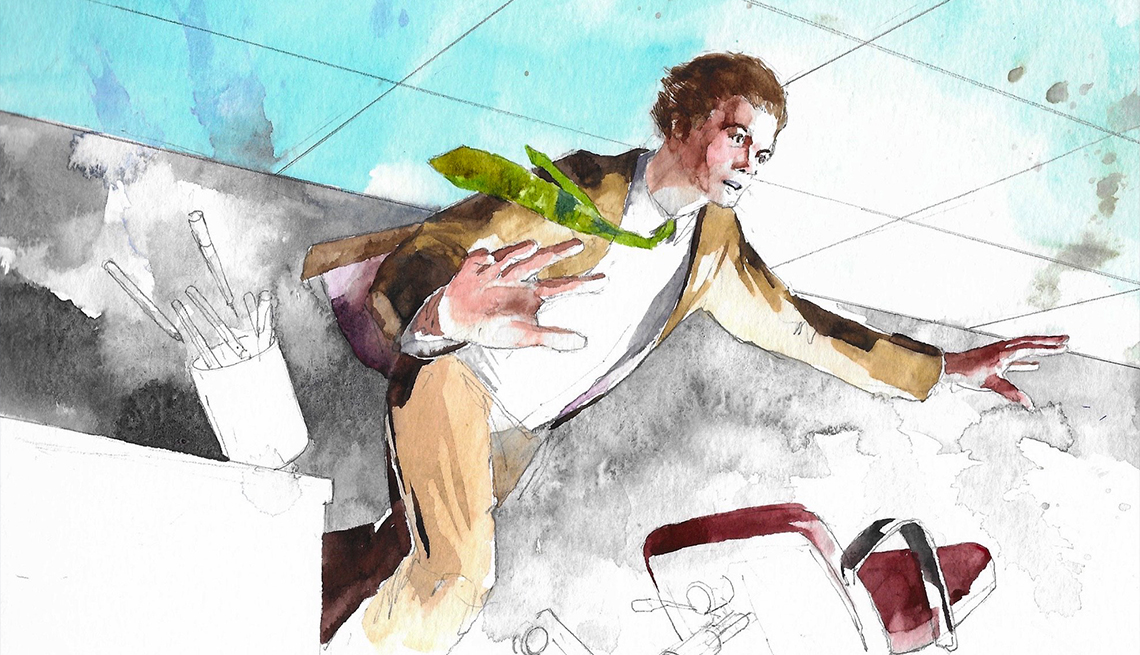

He looked at it. ‘Sorry. I really have to take this.’ He walked out into the garden and heard gulls, the tug of the tide on the shore.

‘Boss.’ It was Jen Rafferty, calling on his mobile. ‘I’m sorry to disturb you. I know you were busy today.’

‘What is it?’

‘I think you need to come in. There’s just been a 999 call. The report of another body.’

Chapter Seventeen

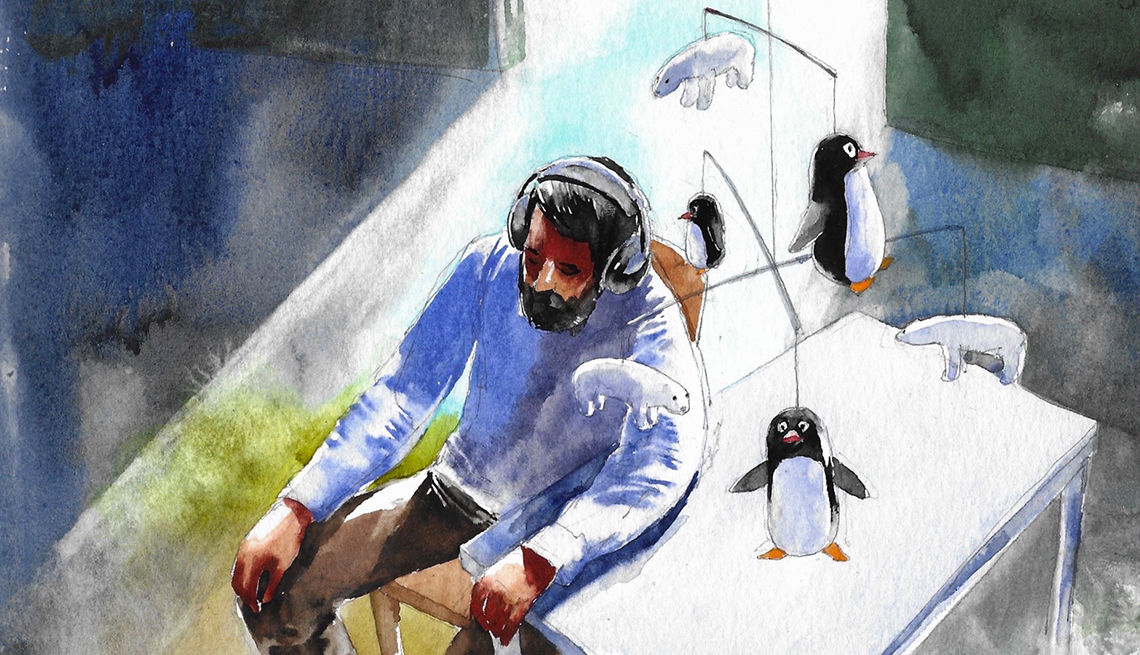

EVE HAD TAKEN HER TIME DRIVING back to Barnstaple. When she arrived at the huge, converted sawmill on the River Taw, which had become the Woodyard arts centre, the place was almost empty. The day centre for adults with learning disabilities was closed at the weekend and there were no classes on a Sunday. No Pilates or community choir. No middle-aged women learning to paint with watercolours. The cafe opened to serve Sunday lunches, but soon that would be closing too. In the quiet of a hot late afternoon, she imagined the timber yard as it had once been, the workers and the machinery, overpowering with its noise. Today, the silence sang out.

There was a marked car park at the front for the centre’s visitors, but she made her way through the big open wooden gates to the back, to the rough concrete yard where the staff left their vehicles. This was close to where Wesley stored his found and scavenged material.

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members