AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Nineteen

ALL THE WAY BACK TO WESTACOMBE, Eve remained silent and still. Jonathan sat next to her in the back of the car. He put his arms around her and pulled her in close to him. He was surprised by the warmth of her skin. He’d almost expected it to be as cold as ice, because she sat white and motionless as if she was frozen. He had a sudden picture in his head, as strange as a surrealist sculpture, of Eve thawing, of the grief flowing out, filling the car and drowning them both.

They were driving against the flow of traffic, a stream of cars on their way back to Barnstaple after a day on the beach, or a long, lazy afternoon in the bars and cafes. Jen made no effort to talk either. Jonathan thought she would become as fine a detective as Matthew one day; she understood emotional trauma and knew that victims had to be allowed their own time frame, their own healing process. Everyone was different.

Jonathan had never previously been to Westacombe, and when they pulled into the farmyard, he was struck by the beauty of it all, distracted for a moment from his reason for being there. The low sun made the place glow, seem magical.

Every colour was heightened, more intense: the red of the brick and tile at the big house and the green of the field next to the lane where black and white cows grazed. From a distance, the thatched cottage could have been a poster for the North Devon Tourist Board. It was all too perfect and not quite real. It seemed flat to him, like a painting or a stage set. In this odd light, it had no depth. The car came to a stop, but Eve made no move to get out.

Jen sat still too. ‘You ready?’ she said at last. ‘No rush, though.’ But she unclipped her seat belt and made to step out of the car.

‘I’ll go in with Eve,’ Jonathan said. ‘No need for you to come.’ ‘

I really should talk to her.’ Jen’s voice was kind enough, but she seemed prepared for battle. This is police business. Nothing to do with you.

‘Not yet,’ he said. ‘You must have got all you needed from Eve at the Woodyard. For now, at least.’ He saw she was about to argue again. ‘An hour,’ he went on. ‘Surely you can give her that to come round, to come to terms with what’s happened?’

Jen seemed to think about it, and Jonathan wasn’t sure what he’d do if she didn’t agree — Matthew would be furious if he upset one of his core team of detectives — but finally she nodded. ‘Okay.’

Jonathan leaned over and undid Eve’s seat belt, then helped her out of the car. ‘Come on, my love,’ he said. ‘Let’s get you home.’ He still had his arm around her shoulders as she led him through the big kitchen and up the stairs to her flat.

They sat together in the airy sitting room, with the window open and a breeze blowing the curtain. Eve still seemed numb. She allowed Jonathan to settle her on the sofa, a cushion at her back, as if she were an invalid.

‘What can I get for you?’ he said. ‘Might you like a cup of tea?’

She smiled and the muscles of her face seemed to be working for the first time since he’d arrived at the Woodyard. ‘I’d much rather have a glass of wine. There’s a bottle in the fridge.’

He fetched it, found a corkscrew in a drawer and glasses in a cupboard, and opened the bottle. He sat on the floor, a low coffee table holding the glasses between them.

‘I was never sure how things were between you and Wesley,’ he said. The words had come out without his thinking about them in advance. ‘I was never sure either.’ She gave another little smile and took a drink.

Jonathan waited for her to speak again.

‘I liked him,’ she said, ‘but not as much as he wanted. Wesley needed adoration, or at the very least a captive audience. I think that was why he couldn’t settle to anything. He made interesting art, but he didn’t believe in it unless somebody told him it was amazing. It was the same with his music. He was less interested in his work than in the reaction it created.’ She looked up. ‘I suppose he just wanted to be loved and perhaps we’re all like that.’

‘Did he love anyone?’

‘Certainly not me, if that’s what you’re asking!’ Her glass was empty. She stood up, went to the fridge in the corner and filled it. She waved the bottle at Jonathan, but he shook his head.

‘Maybe he was a bit in love with Janey,’ Eve said. ‘I saw the way he looked at her and I’d never seen him like that before. He was always hanging round the Sandpiper and he kind of lit up when she was there.’

‘Did she reciprocate his affection?’ Jonathan knew the Mackenzie family. Sometimes there were artistic links between the Sandpiper and the Woodyard. They had different audiences and musicians coming to the region played both venues. He’d always dismissed Janey as hardly more than a schoolgirl, pretty but immature, a bit of a show-off, and he found it hard to imagine the pair as a couple.

‘Oh, I don’t think so. I’d have thought she was well out of his league.’ Eve paused. ‘I don’t know her very well. She’s not been back from university long. I always thought I should make more effort to become friends with her. It can’t have been easy, losing her brother and then being stuck, working in the family business. But somehow the glass always seemed to get in the way.’

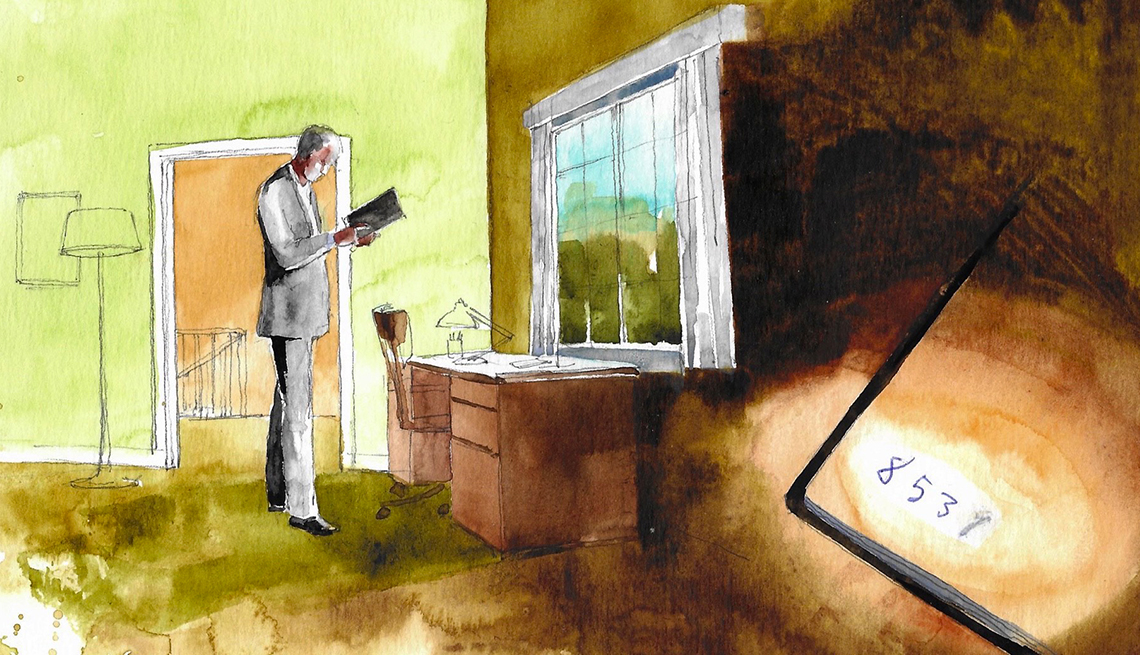

Jonathan stood up and paced around the room. He didn’t want to stay where he was, staring at Eve across the table. Even though he was sitting on the floor, it still felt like an interrogation. Besides, he was always restless and could never sit without moving for long. There was a big family photograph over the mantelpiece and he settled in front of that. He recognized Nigel and Eve and assumed that the attractive middle-aged woman smiling out at him was Helen, her mother. In the background there was a line of dunes, the spikes of marram grass. He wondered where it had been taken.

‘I slept with Wesley once.’ Eve’s words broke into his thoughts and pulled his attention away from the picture. ‘I’d been dumped by a bloke I’d been going out with since university. I was lonely, wretched and Wesley listened. At least, he came here and helped me drink the very nice bottle of whisky Dad had brought back for me from Islay. I thought he was listening. And we went to bed. But it didn’t mean anything. Not really.’

‘A comfort shag,’ Jonathan said.

She gave a little giggle. Perhaps she was already on the way to getting drunk. ‘Something like that. Then I realized that crap telly and chocolate worked much better. I regretted it in the morning and neither of us mentioned it again.’

‘Wesley used to come into the Woodyard cafe,’ Jonathan said. ‘He was always with a woman. Not the same woman each time but the same type.’

‘Older, a bit arty? And I bet they always paid for the meal.’

‘Yeah!’ Jonathan realized then that he’d never seen Wesley at the counter with cash in his hand.

‘Sarah and I called them the groupies. His fans. He kindly allowed them to take him out and buy him dinner.’

‘Who’s Sarah?’ Jonathan thought he was starting to sound like Matthew. Asking questions. He should just let Eve talk.

‘Sarah Grieve. She lives in the cottage on the other side of the yard.’ They sat in silence. Jonathan realized then that Eve was crying, that tears were running down her cheeks. He stood up, fetched a roll of kitchen towel from the bench, tore off two pieces and handed them to her.

‘It was my glass that killed him,’ she said. ‘Just like with Dad. Why would somebody do that? They had to go into Frank’s part of the house and steal the vase and break it. Then they set me up to find him. Who would hate me that much?’

‘I can’t believe that anyone hates you.’

‘Why use my glass then? Why try to point the blame at me?’

Jonathan didn’t have an answer to that. He sat beside her on the sofa and put his arms around her again, stroking her hair away from her face as if she were a child.

Chapter Twenty

WHEN MATTHEW DROVE TO THE FARMYARD, he saw Jen still sitting in her car, the windows open. By now, it was evening, all long shadows and silence only broken by bird calls. He got out of his vehicle and walked towards her, then nodded up towards the attic.

‘How is she?’

‘I don’t know. I haven’t talked to her yet. Jonathan asked for an hour with her, before I started the questions.’

Matthew felt a spark of fury. How dare Jonathan interfere with his investigation and order his staff around!

‘I was just about to go up.’ Jen seemed awkward, uncomfortable, a child caught in the middle of rowing parents. It wasn’t fair, Matthew thought, to have to put her in this position, to have compromised her authority. Jonathan had used his relationship with Matthew to get his own way. ‘The hour’s about up.’

‘I’m sorry you were put in this situation,’ Matthew said. ‘Eve’s a witness and you had better things to do with your time. Jonathan should have known that.’

‘He was just being kind. She’s been through a tough time. She needed the support.’

‘We’re police officers.’ He knew his voice was sharp, hard. ‘Not social workers.’

‘What do you want me to do now?’

Matthew thought for a moment. ‘Go home. It’s not your fault you’ve been hanging around here with nothing to do. Show your face to the kids. I’ve called an early briefing in the morning. Seven thirty. Lots to discuss.’ He paused. ‘In a while, I’m going to talk to Frank Ley.’

‘To see if the glass vase is still in his living room? Or if Eve is right and it was used to stab our victim?’

Matthew nodded. ‘And to see what he’s been doing with himself all day. I’d like to know what he made of Wesley Curnow too.’

He stood until Jen had driven away, trying to calm himself. He was tempted to climb the narrow stairs into Eve’s flat and tell Jonathan to go, but a public row wouldn’t help now and would only embarrass her. That conversation would have to wait until later. He walked round the farmhouse and into the red light of the setting sun.

***

He saw Frank Ley through the living room window. From this angle, Matthew couldn’t tell if the blue vase of flowers was still sitting on the hearth. Frank seemed to be working, to be going through the pile of papers that he’d placed on the arm of his chair. He was wearing little round spectacles, which made him look even more like Billy Bunter. At one point the work seemed to overwhelm him. He took off his glasses and put his head in his hands. Matthew knocked at the door. Frank saw him and beckoned him in. The door was unlocked.

‘Inspector, do you have any news? Have you found out what happened to Nigel?’

Matthew’s eyes were drawn to the hearth. No flowers. No vase. He looked back at Ley. ‘I’m afraid I have other news. Another tragedy, involving Westacombe Farm. Wesley Curnow is dead.’

‘How did he die? Accident? Suicide?’ The words were explosive, the tone so out of character that Matthew was shocked.

Matthew didn’t answer. He kept his voice even, conversational. He knew some of his team considered him dull, but sometimes he used lack of drama as a tactic. A weapon, even. He’d never found that shouting produced results. ‘Was Wesley the type of man who might commit suicide?’

‘I’d never thought of him in that way. But when you mentioned his death, I wondered if the two events might be related.’

‘You thought Wesley might have killed himself because he’d murdered Nigel?’ Matthew thought that was a strange conclusion to jump to. ‘A fit of regret. Conscience. Do you think Mr. Curnow was capable of murder?’

‘I think most of us would be capable of murder, Inspector.’

Would I? Perhaps when I lose my temper, when my reason drowns in the stark, white light, when my control shatters into pieces like Eve’s hand-blown glass.

‘We don’t think Wesley killed himself,’ Matthew said. ‘We believe that he was murdered too.’

Frank looked away. ‘What’s going on here?’ His voice was low, almost mumbling. ‘This is like some second-rate horror film.’

‘He wasn’t killed here. He was stabbed in the Woodyard Centre, in the place where he stored the materials for his work.’ Matthew paused. ‘Eve found him there.’

‘Oh no!’ He stared back at Matthew in apparent disbelief. ‘Not Eve again. How is she?’

‘Very shaken, of course. A friend is with her.’ Until now, Matthew had been standing but he took a seat on the sofa. ‘We have to inform Wesley’s next of kin. I wonder if you know who that might be and how we might get hold of them?’

‘I do!’ The man seemed glad of the chance to help. ‘Their names are Martin and Liz. Martin was a financial journalist and I knew him through my work. I’ll get their phone number. They moved to France when they retired, to live the good life in the Dordogne.’ Francis fumbled for his phone, his hands trembling, and passed it to Matthew so he could make a note of the numbers.

‘Is that how Wesley came to be living here? Because you were a friend of his parents?’

‘The family were from Cornwall. That gave Martin, Wesley’s father, and me something in common when I was in London. We worked in different fields, of course, but we were both West Country boys. Both interested in the politics of money. Wesley was always happier staying with his Cornish grandmother than in the city, and spent all his holidays there; he ended up at school in Truro.’ Frank paused. ‘He tried all sorts when he left, but he couldn’t settle. He dropped out of art school, ran a bar in Newquay for a couple of seasons, but couldn’t make it pay, joined a band for a summer. All the time his parents were subsidizing him. Not really doing him any favours. By then he was in his thirties, almost middle-aged, and he’d never really earned his own living. In the end, they decided to cut him loose.’

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members