AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Twenty-Two

THE SANDPIPER WAS CLOSED ALL DAY ON MONDAYS. ‘Our one day of rest,’ George said when Jen called to make an appointment. ‘Yes, we’ll all wait in to speak to you. Come to the house. That’s where we’ll be.’

The house was whitewashed and, like the cafe bar next door, it faced the sea, only separated from the beach by the narrow road. There was a wrought-iron balcony on the first floor, and that was where Martha was standing when Jen parked outside. She was leaning against the rail, holding a cigarette in one hand, blowing the smoke towards the shore. Martha Mackenzie had been part of Jen’s childhood — the soap she’d acted in for more than thirty years had been required early evening TV viewing — and, despite herself, Jen was aware of the woman’s celebrity. There was a thrill in meeting someone so famous.

‘You must be the detective.’ Martha’s voice was deep and it carried. A woman walking past with a buggy turned to stare. She recognized Martha too and gave an excited little wave. Martha waved back. Graciously. ‘Just a mo and I’ll be down to let you in.’

The young mother looked at Jen with a touch of envy and walked on.

Jen had seen Martha before in the bar, a glamorous presence with a small crowd around her, but they’d never been introduced. It seemed Martha recognized her, though. ‘Of course, you’re Wesley’s chum. Poor Wesley. You must be devastated. We all are.’ She reached out and gave Jen a hug, surrounding her with the smell of cigarette and expensive perfume. Jen wondered what Venn would say about an interview beginning with such informality. But then he’d told her to put the family at their ease.

Eventually, Martha pulled away. ‘Come on through. The others are still finishing breakfast but I was desperate for a ciggie.’

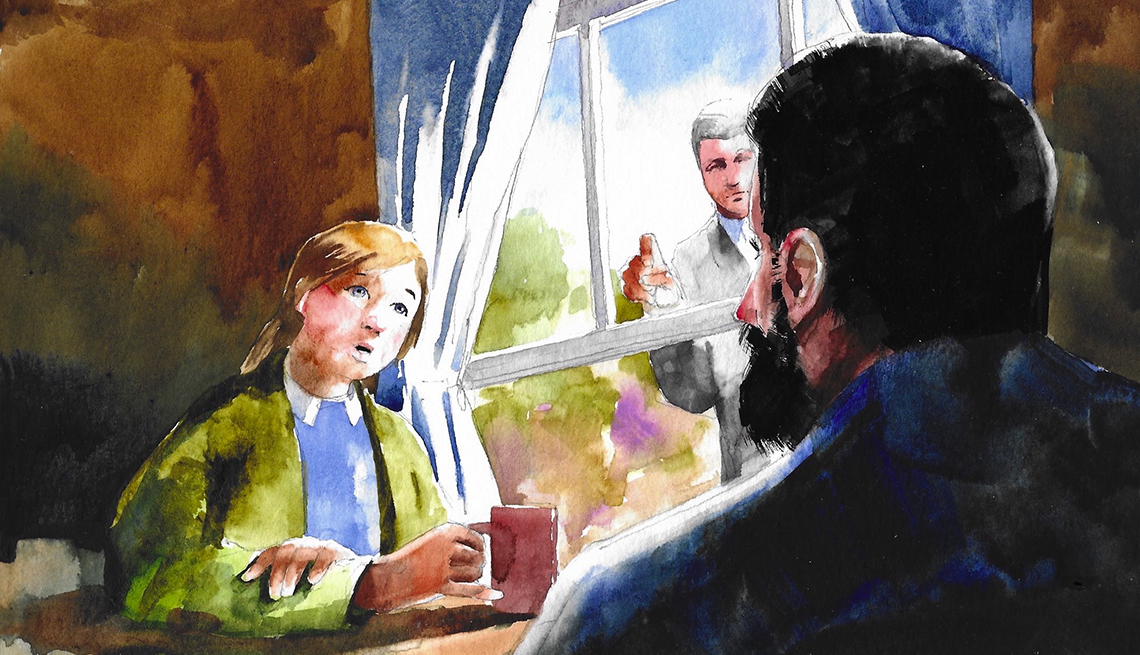

The kitchen was long and narrow and ended in double glass doors leading onto a patio garden, with terracotta pots and rough stone walls covered with climbing plants. One shelf ran right along the room’s longest wall. It had been painted yellow and held strange trinkets, bits of brightly coloured pottery and glass, shells, tiny carvings that might have been made by Wesley. The doors were open, so the kitchen and the garden seemed like one space. George and Janey sat inside at a light-wood table. There was a jug of coffee, a plate with a remaining single croissant.

‘We have a late breakfast on Mondays,’ Martha said. ‘It’s become rather a ritual.’

Janey looked up and gave a little smile. Jen thought she might be about to say something, but in the end, she continued to stare into her mug. She seemed exhausted, blank. George stood up and held out his hand. ‘Jen,’ he said. ‘How lovely to see a friendly face. I worried they might send a stranger.’

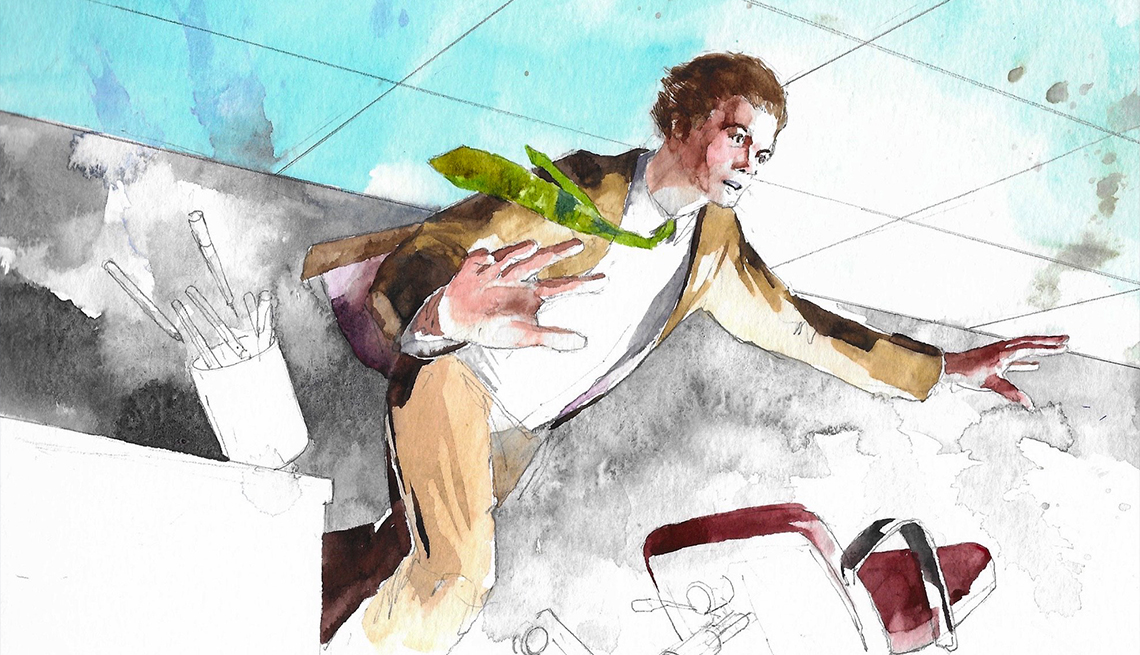

‘This isn’t a formal interview,’ Jen said. ‘That will probably come later because you all knew both victims, and I won’t be allowed to take part in that. This is an initial chat to see if you might be able to help.’ Her attention was caught again by the yard outside. ‘You’ve made it so beautiful here.’

‘That was Mack,’ Janey said. ‘His design; his work. You should have seen it when we first moved in! We’re trying to keep it going for him but none of us has his green fingers.’

George was still on his feet, pouring coffee. ‘Would you like anything to eat? That croissant won’t be so nice now, but I can make you toast. Eggs, maybe?’ Speaking with the Scottish accent that had always set him apart.

Jen shook her head. ‘I’m afraid I have questions.’ ‘Of course you do, darling,’ Martha said. ‘That’s why you’re here.’

‘Did either of you see Wesley yesterday? You were friends. Perhaps he called in?’

‘I didn’t see him,’ George said. ‘One of my chefs was off sick and I was in the kitchen for most of the day. I hardly went into the bar at all, except to cover for Janey when she went off to speak to your colleague.’

‘Your staff will be able to confirm that?’

‘You’re asking if I have an alibi?’ He sounded amused, unoffended. ‘We close early on a Sunday. There are so many places here serving Sunday lunch and we don’t feel the need to compete. So, our regulars come for breakfast or brunch and we close in the early afternoon. I have an alibi until then, and one of your officers came to talk to Janey. After that, no.’

‘Where did you go?’

‘I drove inland,’ George said. ‘I wanted to get away from the crowds for a bit. There’s a place near Torrington where Mack loved to walk. He was a great walker. Seal Point was his favourite place, but I knew that would be packed on a Sunday afternoon so I headed inland instead. I got back at about six.’

It seemed a long explanation to a simple question, but George had always been garrulous. Jen turned to his wife. ‘You didn’t want to go too?’

The woman smiled. All her features were large and her smile was generous, wide. She was wearing lipstick. Jen thought about that: the effort of putting on make-up just to be in the house. Every day a performance. ‘Walking’s not really my thing. Not in this heat. I went and lay on the bed. Dozed for a while. The idea of a siesta is very civilized, don’t you think? I didn’t wake until George came back.’

Throughout the exchange, Janey had been silent, unresponsive. Now she looked up. ‘I suppose you want to hear about me.’

‘Please.’

‘When I came off shift, I had a shower, changed, then I headed out. I wanted to escape this place too. It’s crazy in the summer. Sometimes, I long for grey days, a storm from the west, just to keep people away. Pouring rain. I wonder why I ever came home. But I couldn’t drive. I’d parked in the lane by the side of the bar and some bastard tourist had boxed me in. I was really, really pissed off, wrote a note and stuck it on his windscreen, made a record of his registration number, thinking I’d dob him in to the parking guys. I never did, of course. Couldn’t be arsed and it seemed a bit petty. In the end I went for a walk. Out past the cricket club towards Fremington Quay. It was a bit quieter there. Still lots of people about, but not crazy busy.’

‘Do you still have a note of the car’s registration number?’

‘Nah,’ Janey said. ‘At least probably not.’

‘You might want to look,’ Jen said, ‘just in case.’ There was a moment of silence while the implication of that sunk in, but there was no response. No righteous indignation. Janey just nodded in agreement. ‘I’m sure I can dig it out.’

‘And the family just has two vehicles? You don’t have your own, Mrs Mackenzie?’

‘No,’ the woman said. ‘If I need a car, I use George or Janey’s.’

‘You all seem to have been close to Wesley. How did you meet him?’ Jen thought the more general question might put them at ease, start a natural conversation.

‘He was a regular in the bar,’ George said, ‘and he had a way of making you feel like a friend. Of wanting to be his friend. We run a business but I found myself buying drinks for him. Just as well he was one of a kind because we’d have gone under if I treated all my customers as drinking pals.’

‘I’m not sure how close we really were,’ Janey said. ‘I think at heart he was an actor. It was subconscious. Like you, Mummy. He became the person we all wanted him to be. He was great to have in the bar because he could lift the mood. He’d walk in and suddenly he made everyone feel cleverer, more amusing. But what lay under the charm?’ She shrugged. ‘I don’t think we’ll ever know now.’

‘Had he upset anyone recently?’

Another silence. ‘This is going to sound very petty,’ Martha said. ‘Not something that could ever trigger murder.’

‘All the same,’ Jen said, ‘it would be useful to know. That’s why I’m here drinking coffee with you and we’re not taking statements. I’m after background, the gossip.’

‘He had a way of charming middle-aged women.’ Martha sounded dismissive. Maybe she didn’t consider herself middle-aged. ‘Perhaps he made them feel younger, though he was no spring chicken himself. Wherever he went, they were around him, giggling, buying him meals and drinks. But he had one special admirer. Cynthia Prior. Of course, you know her.’

Jen nodded.

‘Her husband’s a dry old stick who doesn’t share any of her interests. Cynthia considered Wesley a sort of cultural companion. She’d think nothing of taking him to London to see a show that interested her, or dragging him round an exhibition. All expenses paid, of course. First-class rail and a fabulous meal at the end of the evening. In return for his company. But recently, he’d been seeing a lot less of her. It’s possible that Roger finally put his foot down. I don’t know him well, but I imagine he’s a man who would care about appearances. But I had the impression that Wesley was the one who’d started to keep his distance.’ Martha turned to her daughter. ‘What do you think, Janey? You probably knew Wesley better than the rest of us.’

Janey shook her head as if she had no answer. ‘I don’t know what was going on. Like I said before, nobody really understood Wesley Curnow. He was a mystery to us all.’

‘Was he close to Mack?’ Jen thought that might be another link between their victims. If the two were friends, Wesley could have been supporting Nigel’s campaign to investigate the young man’s death.

‘Wesley didn’t really like people who made demands on him,’ Janey said. ‘It was always the other way around. And depressed people can be very demanding. I think Mack was hurt because Wes kept his distance during that last episode of illness. When they let him out of hospital, he got in touch with Wes, and asked to see him. When there was no reply to his texts and calls, Mack walked up to Westacombe. He was so restless at that time, so impatient. He was pacing, talking to himself, hearing strange voices. Wes just didn’t know how to handle a madman landing up on his doorstep. All that real emotion was too much for him. In the end, he phoned me and asked me to take Mack away. Mack was crying all the way home in the car. I suppose it must have seemed like the worst kind of rejection from someone he’d admired and considered a friend. That was the day before he killed himself.’

‘You must have found that very hurtful.’

And yet you still hung out with Wesley. You were dancing with him at Cynthia’s party.

‘Not really. I could understand how Wesley found it uncomfortable. I’d probably have reacted in just the same way if Mack hadn’t been my brother.’ Janey paused. ‘We’re all supposed to be open about mental health these days. Very sympathetic. But the reality of the bloody thing, the person’s self-obsession, the relentless movement, like they’re constantly wired, the tedious repetition of paranoid thoughts, that hasn’t changed. You can’t know just how exhausting severe depression can be for other people until you’ve experienced it.’ She looked up. ‘I’m sorry. That sounds callous. But it was incredibly painful to deal with. That was why we needed the health professionals, partly just to take over some of the responsibility, but to give us hope that they could make Mack better and keep him safe. We couldn’t do it any more. And the health service let us down.’

‘Did any of you feel that Wesley was responsible for Mack’s death?’

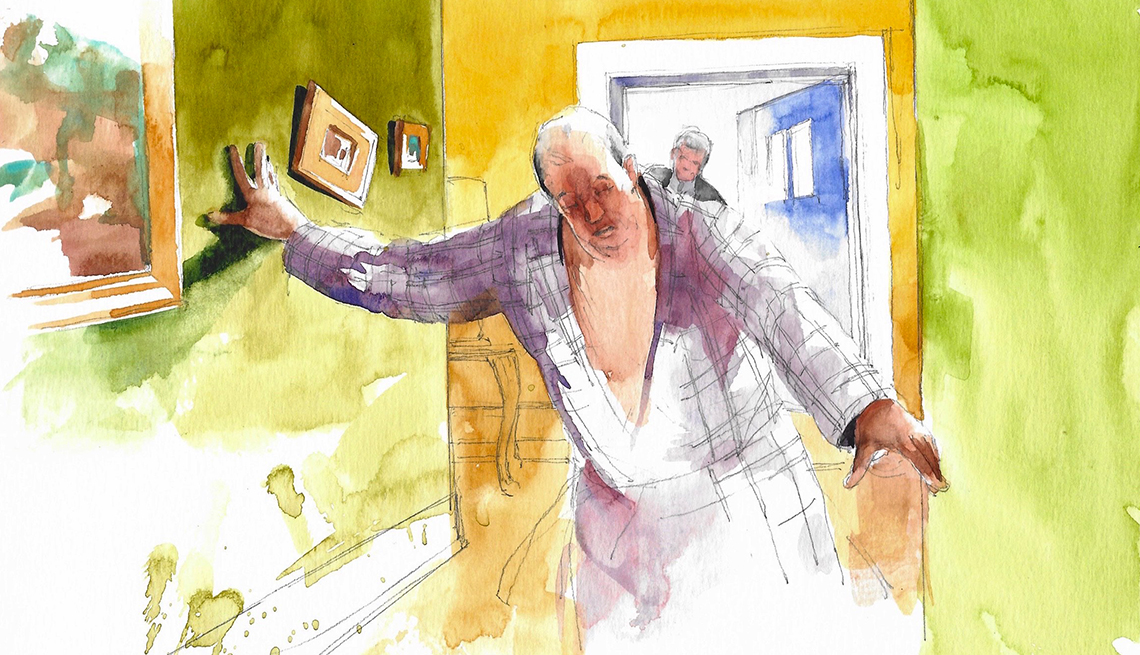

‘No!’ George’s response was immediate. ‘That was the health service. They mismanaged the whole case. I phoned them when Janey brought Mack back from Westacombe in such a state. I phoned his consultant. His secretary said he’d phone us back, but of course, he didn’t. I phoned the community support team. Again nothing. Apparently, my son wasn’t sufficiently suicidal to warrant immediate intervention. And he had family support. The hospital had prescribed medication to help Mack sleep and we gave it to him that evening and made sure he was in bed. We thought he was asleep. The next day was Monday — our day off — and the rest of us were later getting up than usual. As Janey said, we were all exhausted. When we woke up, there was no sign of Mack. Maybe he hadn’t swallowed the pills or maybe they weren’t as strong as we’d imagined. We all went to look for him. Frantic. You can’t imagine what it was like. I still have nightmares … Then we discovered that he’d taken his car.’

‘Who found his note?’

‘Some holidaymaker,’ Janey said. ‘Dad called the police when we realized Mack’s car was missing and they found it outside our chalet in the dunes. His body didn’t turn up until several days later, washed ashore on the north end of Lundy, pulled out by the tide.’

When George turned to face Jen, there were tears running down his face, and when he spoke, the words were sharp and jagged. ‘That wasn’t Wesley’s fault. He wasn’t trained in mental health. It wasn’t even the fault of the poor sods who let him discharge himself too soon, and then were too overstretched to respond when he had a crisis. It was the system. And I want the whole world to know how it let my son down.’

Jen didn’t know what to say. She’d been in the bar a couple of times since Mack’s death. George had been his usual urbane self, accepting the condolences of regulars with a hug of thanks, a few grateful words. There’d been none of this anger. Now, she thought he must be as fine an actor as his wife, to have persuaded them all that he’d accepted the death of his son with grace.

She got to her feet. ‘I don’t want to disturb you all any further, but I wonder if I could chat to Janey?’ Jen turned to the woman. ‘It sounds as if you were as close to Wesley as anyone. We could go into Instow. Get a coffee.’ She thought there were things she’d never want to say in front of her parents.

‘Sure,’ Janey said. Then after a moment’s thought she added, her voice tentative, ‘Could we go to Seal Bay? Have a little walk on the point? It was Mack’s happy place. I was planning to go this morning. It won’t be so busy today.’

Martha put her arm around her daughter’s shoulder. ‘Are you sure, darling? Won’t that just bring everything back?’

Janey tensed under the touch. ‘Don’t you think these murders haven’t brought it back already? The nightmares. The flashbacks? I kept waking up last night. I’d drift back and then be haunted again.’

Her voice was angry, bitter and Jen saw that the young woman’s hands were trembling. She couldn’t imagine what it must be like, to be reminded over and over of the loss of a brother.

‘There’s nothing I’d like better than a wander by the sea in the line of duty,’ Jen said, ‘and we’ll get an ice cream. My treat.’

***

They parked by the Mackenzies’ chalet, but they didn’t go inside. The building was made of wood and the paint was peeling; it was less grand and impressive than some of the others, but Jen could see how it would appeal to a couple of kids. It would be the best kind of den.

Janey led her through the dunes, across the beach and onto the coastal path. They didn’t start talking until they were on their own, facing out to the sea. It was as smooth as oil, glittering in full sunlight. As Janey had said, the path was relatively quiet.

‘Tell me a bit more about Wesley,’ Jen said. ‘How close were you?’

But Janey had stopped where the cliff was closest to the water and was looking out towards Lundy on the horizon.

‘This is where they found the note that Mack left for us.’

‘What did it say?’

‘That he needed to find peace at last.’ Janey looked back at Jen. ‘I feel like that now. These murders. It’s like blow after blow. As if you’ve been mugged and someone’s kicking you, over and over again. Just as you think it’s all over, they come back to hit you.’

‘You’re not feeling suicidal, though?’

There was a moment’s hesitation before she answered. ‘Nah. Don’t worry. I’m a survivor. Poor Mack wasn’t.’

‘So, tell me about Wesley, if you feel that you’re up to talking about it, if it’s not one kick too many.’ ‘Yeah, I’m okay. It’s good to get away from the house. We’ve all been affected by Mack’s death in different ways. Mum and Dad are all, like, we’ve got to keep the show on the road. It’ll get to them sometime, though.’

‘I think it’s already got to them. They just have different ways of dealing with it.’

‘Maybe.’ Janey was still staring out to sea. Lundy was shimmering in the heat haze on the horizon. ‘Wesley was a bit of a drifter. High-achieving parents, with plenty of money, but not much time to give to their son. That was how I read it at least. He always said that his grandmother was more like a real mum.’ She gave a little laugh. ‘I think she spoiled him rotten. Perhaps that’s why he liked her so much. And why he got on so well with all his middle-aged female groupies.’

‘How did he seem at the party?’

‘Just as he always did. Pretty chilled. Making sure he got more than his fair share of the food and the wine. That was classic Wesley.’

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members