AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Twenty-Five

AFTER DROPPING JANEY MACKENZIE IN INSTOW, Jen Rafferty made her way back to the police station. She tracked down the registered owner of the vehicle which had blocked Janey in the afternoon before and gave him a call. He was belligerent, blustering.

‘The council should have reserved parking for locals. All those people coming from outside, taking up our spaces, when we just want to take the kiddies to the beach. I didn’t know I was doing any harm.’ He had a Brummie accent. Not so local himself. But he’d confirmed Janey’s story. She hadn’t driven into Barnstaple the day before. Not using her own car at least.

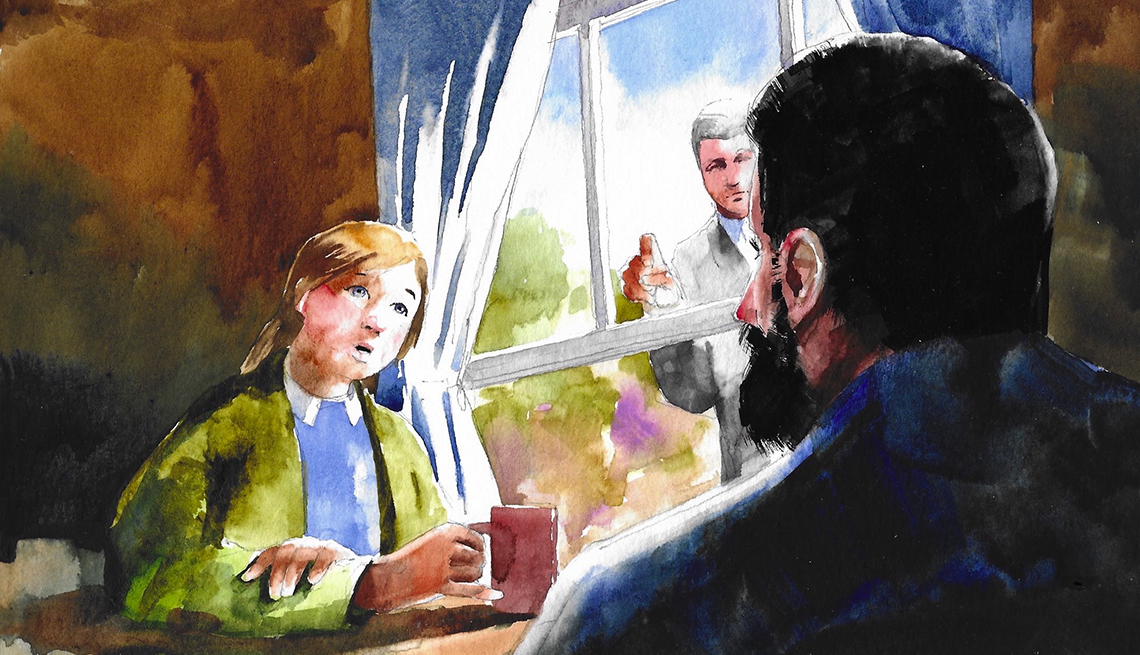

Jen wanted to talk to the mother of Luke Wallace, the teenager who’d committed suicide in London, the lad whose death had forced Roger Prior to resign from his high-profile post in Camden. She’d contacted the woman through the ‘Love Luke’ Facebook page, and they’d arranged to talk on the phone. Matthew Venn was still out and Jen used his office to take the call. This wasn’t a conversation to be had with the noise of the open-plan room in the background.

‘Detective Sergeant Rafferty.’ The woman sounded calm, normal. Jen wasn’t sure what she’d been expecting. A nutter perhaps. Someone hysterical. Or greedy, just desperate for compensation. ‘Thanks for getting in touch. How can I help?’

Jen had planned how to approach the woman carefully. It wouldn’t do to suggest that Roger Prior was a killer. Or even to link him to the investigation. Jen might not like the man, but she couldn’t be the person to ruin his career without evidence. For one thing, Cynthia would never talk to her again and Jen was already missing her support and friendship.

‘We had another suicide, much like Luke’s, here on the North Devon coast. Our officers were involved. We want to prepare them for any possible future case, perhaps put together a training package to help them deal better with people with severe depression. I hoped you might be able to help, to give the signs to look out for.’ And all that, Jen thought, was true. She’d be prepared to put together a training module herself. She knew what depression felt like.

‘But that’s brilliant!’ Jen hadn’t been expecting such an enthusiastic response and felt a little uncomfortable. The woman went on: ‘Of course, the police have to be at the front line when it comes to mental illness these days. The health service has been cut so much the police have to take up the slack.’

‘You felt your son was let down by the NHS?’

‘He was! I don’t blame any individual, but there just wasn’t anyone there when we most needed the support.’ She paused. ‘There were other influences. He’d found his way onto one of those foul suicide websites.’

‘What are those?’ Jen looked on Venn’s desk for a pen to take notes. They were lined in a row next to a neat pile of scrap paper. Of course they were.

‘There are chatrooms where people come together to celebrate dying, to encourage members to take their own lives,’ Luke’s mother said. ‘That was how it seemed to us at least, though they say they’re just offering support.’

‘Is there any way I could find out if the local young man who died here had accessed one of those?’

‘I don’t know.’ The woman sounded uncertain. ‘I can send you the link to the one Luke used. It was called Peace at Last. You might be able to trace the information through that. But the sites change and move, and they’re not illegal.’

‘I understand that the head of the trust resigned soon after your son’s death. He must have felt some responsibility.’

‘He was forced to leave.’ Now the woman’s words were harsh and bitter. ‘And he moved almost straight into another cushy, well-paid post in a different part of the country.’ There was no mention of where Prior had taken up his new post. Perhaps she hadn’t cared enough about the details to find out.

‘Has anyone else been in touch with you?’ Jen asked. ‘We’ve been working closely with an organization called Patients Together and their senior officer, Dr Nigel Yeo, was looking into the young man’s death here.’

‘Yes! Soon after Luke died, we had lots of enquiries, more than I could remember, but that was a recent one.’ ‘Was Nigel in touch by phone?’

‘By email first and then we had a phone call. I told him what I’ve just told you.’ For the first time in the conversation, the woman sounded uncertain. ‘If you’re working together, can’t you just ask him?’

‘He died,’ Jen said, ‘very suddenly. That’s one reason for my call.’

There was a silence. ‘Oh,’ the woman said. ‘I’m so sorry. We only had that one conversation, but he seemed such a lovely, caring man.’

***

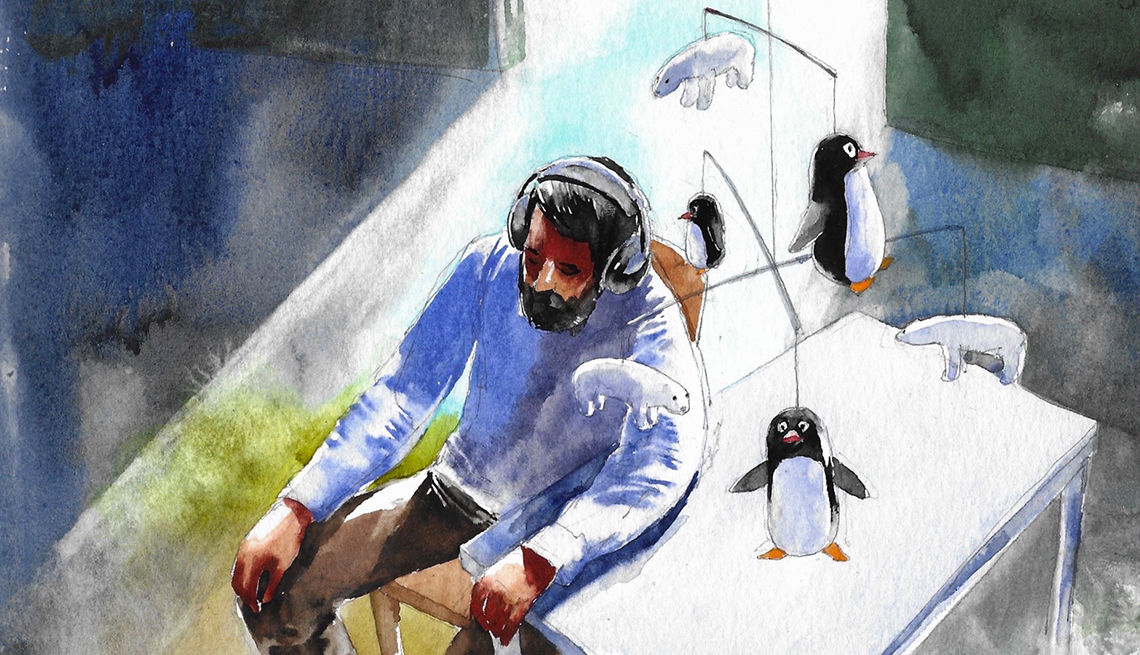

Jen wandered back into the main office. There was still no sign of Venn, but Ross was there. Of all the team, he was the most tech savvy. She explained about the suicide forum and Luke Wallace. ‘If we get hold of Mack’s laptop, would we be able to tell what he’d been into?’

‘You think that might be relevant?’ Ross, as ever, seemed dismissive of any idea that wasn’t his. Or Joe Oldham’s.

‘Yeah, I do. What if Nigel Yeo had found out, in the course of his investigation, that Mack had been encouraged to kill himself on one of those sick sites? You told me Mack’s psychiatrist said Yeo was furious the afternoon before he died. Discovering that Mack had been provoked to suicide might have made him even angrier than if he’d thought it was down to the hospital’s negligence.’ Jen thought for a moment. ‘According to Janey, Mack’s suicide note said he was looking for peace at last. That’s the name of the chatroom Luke had accessed.’

‘It could be a coincidence …’

‘Yeah, it could. But it does fit in with all the facts.’

‘You believe Yeo might have traced this suicide site to someone local?’ Jen could tell that Ross was more interested now. She thought if she wasn’t careful, he’d claim the idea as his own.

‘I hadn’t thought that far, but maybe.’

‘It’d have to be some nutjob, provoking a kid to kill himself. Can you think of anyone involved who might be that wacko?’

Jen shook her head. She suspected Wesley might have looked at the site, not because he was suicidal but because he’d always been curious about the strange and the perverse. He said it fed into his art. Wesley was dead too, though, and that didn’t fit with the theory. ‘It’d be great if the tech guys could check Mack’s laptop, if I can persuade the family to hand it over to us. Luke’s mother sent me a link to the site he was using. Wouldn’t it be interesting if Mack had accessed it too?’ She paused. ‘Nigel Yeo had phoned Mrs Wallace the week before he died. One coincidence too many, do you think?’

Ross was just about to answer when Jen saw Joe Oldham approaching. The superintendent was a big man. Once he might have been fit; he was the leading light in the rugby club after all. Now he was flabby, with a florid face suggesting a heart attack about to happen. He could have retired months before, but Jen thought he liked the status, the power. He’d have nobody to bully at home.

‘Where’s Venn?’ The superintendent didn’t hide his distaste.

‘At Westacombe following up an inquiry with Mr Ley.’ Jen paused. ‘He’ll be back in an hour for the briefing, if you’d like to join us.’ Knowing Oldham was on his way out for his first drink of the evening and that it was a compulsion he’d not be able to resist.

‘Nah,’ Oldham said. ‘Don’t want to interfere. Don’t want it said I don’t trust my team. Tell Venn to keep me updated.’ He waddled away. His breathing was so poor that Jen almost felt sorry for him. Almost, but not quite, because he was a poisonous sod.

She waited until he’d left the room before speaking again. ‘I’ll phone George Mackenzie, see if he’ll let us have Mack’s laptop.’

‘I’ve got a friend in tech. A wizard. You get it, I’ll make sure he does it himself and fast-tracks it. We can sort out the budget later.’

She smiled. She enjoyed these moments of collaboration with Ross, thought he might not be such a dick after all. She got out her phone to call Mackenzie. By the time she’d finished, Venn was back and the meeting was about to start.

***

Venn was unusually informal, with rolled-up shirtsleeves, no jacket. He looked flushed, as if he’d been in the sun. He stood at the front, beside the large whiteboard, and as always, they quickly fell silent. Jen wished she had that authority.

‘It’s been a busy day,’ he said, ‘though I’m not sure how far we’ve got. More questions than answers, I think. Ross, can you take minutes, and get them out to the team as soon as possible? There’s too much information to take in at a sitting.’

Ross nodded and got out his iPad. Throughout the briefing, Jen heard him tapping on the keypad, a background rhythm to the conversation.

‘Shall I start?’ As Venn leaned back against the desk, Jen saw that there were grass stains on his pale summer trousers. She was astonished. She’d never before seen him anything but immaculate. ‘Ross and I met the team at the hospital this morning. Their head of comms was very much in charge and she seemed more concerned about the hospital’s image than providing any useful information. Mack’s psychiatrist, Ratna Joshi, was more forthcoming when we saw her on her own, though, and implied that something had disturbed Yeo later that day. Jen, could you go and see her tomorrow?’

Jen nodded and Venn continued. ‘Patients Together, headed up by Yeo, seems to have been pretty dysfunctional. I had the impression he was easing out the dead wood—the woman in charge of finance had taken redundancy—and that Lauren was the only staff member he trusted.’

‘Sounds pretty ruthless,’ Ross said.

‘Maybe. Or maybe he took his role seriously and wasn’t prepared to tolerate hangers-on.’

Matthew paused and looked around the room again to check that he had their attention. ‘I had a quick visit to the Woodyard. Lucy Braddick says Wesley was in the cafe on Sunday afternoon and waiting for someone, who didn’t turn up.’ He glanced around once more to make sure they all recognized Lucy’s name. They did. Lucy was a hero to the team. ‘Usually he met one of his middle-aged lady friends there, apparently. I’d like to get a handle on who those women were. Wesley might have confided in one of them.’ A pause. ‘Ross, that’s for you.’

‘Start with Cynthia Prior,’ Jen said.

‘The magistrate?’

‘Yeah, she was his biggest admirer. And of course, she’s linked to the case because her husband’s head of the trust. And Roger Prior was in charge of the trust where Luke Wallace killed himself. An interesting coincidence.’

‘I met Prior at this morning’s meeting.’ Ross paused. ‘A cold fish.’

‘Arctic,’ she said.

‘Finally,’ Venn said, ‘I went to visit Frank Ley. While I was waiting for him, I found a shortcut to the main road between Barnstaple and Instow. It goes through his garden and over a bit of common land. We can’t assume that just because a Westacombe resident didn’t pass through the checkpoint at the farmyard, they couldn’t have killed Wesley Curnow.’

Jen thought Venn had finished and would ask her to take over, but he went on:

‘It seems that Ley has been the target of a hate campaign over one of his developments. I’m not sure how that can be relevant, but if his connection to the murders comes to light, it could be an excuse for the press to start thinking conspiracy theories and cover-ups. I’ll check it out.’ Now, he did nod towards Jen to continue.

She described her visit to the Mackenzies’ house in Instow. ‘They’re much angrier about the way Mack was treated than I’d realized.’ She turned to Venn and again explained what she’d learned from her call to London. ‘Dr Yeo had phoned her too, not long before he was killed. Ross and I wondered if Mack Mackenzie had used the same site. In his suicide note, he wrote that he was finding peace at last, and Peace at Last was the name of the group Luke had joined. We wondered if there might be a connection.’

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members