AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Thirty-Seven

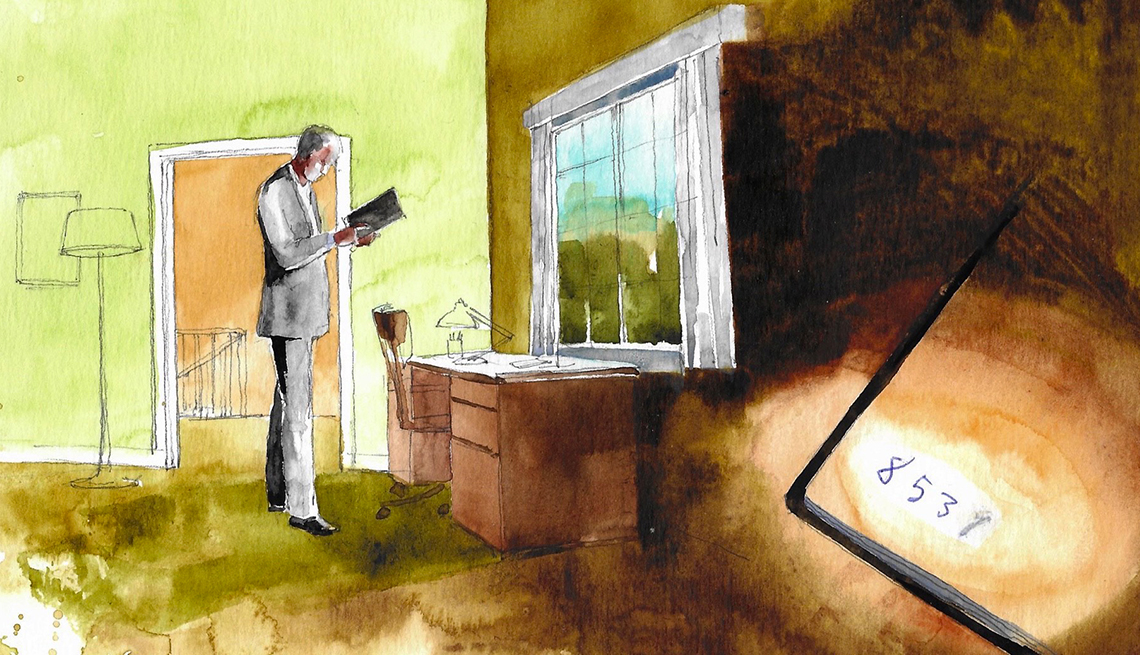

ROSS FOUND THE WHOLE MACKENZIE FAMILY together in the Sandpiper. Venn had asked him to notify them of Frank Ley’s death:

‘They were friends and another suicide will hit them badly. It’ll bring back the details of their son’s death.’

By the time Ross got there, it was late afternoon and the cafe had been closed to the public. Inside, they were preparing for the evening’s event. Posters on the wall advertised a play, a performance of Waiting for Godot by a small Cornish touring company. Ross had heard of Beckett but knew nothing about him, except that he was obscure. He was put off by anything that reminded him of school. When he pushed open the door, he walked into darkness. There were heavy blinds on all the windows. A loud woman’s voice shouted at him from the gloom.

‘Sorry. We’re not open, not even for the bar.’

It wasn’t Janey. Someone older. A loud, confident, superior woman’s voice that rankled. Her mother, perhaps.

‘It’s DC Ross May. I need to talk to the Mackenzies.’

Just as his eyes got used to the shadow inside, a spotlight was turned on and blinded him. He wondered if that was deliberate and, again, he felt awkward.

‘Sorry.’ This time the apology did come from Janey. ‘We’re just getting ready for this evening’s play.’

The house lights came on and he saw that the cafe was being transformed. They’d built a low stage at one end of the room and rows of chairs faced it. The counter which had served sandwiches and cream teas during the day was now set up to provide wine and cocktails. Ross thought Mel might like it here. He should bring her here one evening, though not to see a piece of theatre they would probably both struggle to understand.

Janey was wearing a black T-shirt, with a Sandpiper logo, and frayed jeans. Her parents were at the back of the room, working on the lighting. Ross recognized Martha Mackenzie because his mother was a fan of her TV soap. She shouted out to him again, the voice slightly too loud, slightly patronizing.

‘This is really not a good time, Constable. And we’ve told your colleague all that we know.’

‘I have some news.’ Then he repeated with more authority. ‘I need to talk to you.’

The older couple moved from the back of the room. Janey pulled three of the chairs into a semicircle and they sat, looking at him. Again, he felt a little daunted. Martha was wearing a silver tunic over wide black trousers. Her make-up was dark and dramatic — heavy black eyeliner and mascara, with dark red lipstick — but still she seemed to glow, to pull his eyes towards her. ‘Well?’ she demanded. ‘What do we need to know? Have you found the killer? Is that it?’

‘I’m afraid there’s been another death.’ It wasn’t how he’d planned to tell them. He’d put together some words driving from the farm. I know Mr Ley was a close friend and this will come as a shock.

‘Who?’ This was Janey. She seemed horrified by the news. In the strange theatrical lights, her face seemed very pale, her eyes wide and large. Like something from a cartoon. Not real at all. None of this seemed quite real.

‘Francis Ley.’

‘Not Frank!’ George Mackenzie’s response seemed the most genuine. ‘No.’

‘He was found on the common near to his garden this morning.’

‘How did he die?’ George demanded. ‘Was he stabbed like Nigel and Wesley?’

‘We won’t confirm cause of death until after the postmortem, but it seems that he committed suicide.’

There was complete silence.

‘He had everyone round for drinks the night before last,’ Janey said. ‘The Grieves and Eve, and us. A kind of commemoration of three lives lost. That was what he said.’ She paused. ‘But perhaps it was his way of saying goodbye.’

‘How did he seem?’

Now Martha did speak. ‘Bloody sad! As we all were. We were mourning three people close to us. And now, it seems, he was contemplating taking his own life too. And you ask how he was! Good God.’ She stood up, pushing back the chair so violently that it fell over. ‘I’m going outside for a fag, and to look out for those actors.’

She left and the room seemed very quiet. ‘Please forgive my wife,’ George said at last. ‘She’s very upset.’

Ross was thinking that this whole conversation could have come straight out of a play. Everyone’s response seemed stilted and unnatural.

George shifted in his seat. ‘Look, we should be getting ready for the evening’s performance. You don’t think we should cancel? We’ve got a full house.’

Ross thought for a moment. ‘No,’ he said. ‘No need for that.’

As he was leaving the bar, a battered minivan drew up outside and half a dozen people climbed out. Martha was there, greeting them, hugging them as if they were all old friends. Ross presumed they were the actors. As he walked away, he heard her loud voice carrying down the street. ‘Come along in. We’ve had a bit of sad news today, so we’re not quite as organized as usual. But of course, the show will go on.’ He thought she sounded desperate, as if she was trying too hard to convince the world that she was in control.

***

At the evening briefing they concentrated on the possibility that Ley had been a member of the Peace at Last forum.

‘We need your friend to come up with that information,’ Venn said. As if it was Ross’s fault that Steve hadn’t yet provided the goods.

‘Could Ley have been the killer?’ This was Jen. ‘His suicide wasn’t triggered by a very different kind of guilt?’

‘Superintendent Oldham has already suggested that theory.’ Venn’s voice was bland but they could all tell he didn’t think much of it. ‘It would be very neat, of course, but really, I don’t see it. What motive would Ley have for killing Nigel and Wesley?’ He looked up at them sharply. ‘And I refuse to blacken a dead man’s name without real cause.’

It was just the core group tonight. Venn had bought in pizza, and they’d pushed a couple of desks together and sat around pulling the slices apart with their fingers. No plates and no napkins, though the boss had found a roll of paper towel somewhere. If there’d been beer, it could have been a student party.

‘Could Ley have been provoked to kill himself?’ Jen asked. ‘If he was a member of the Suicide Club?’

‘It’s something to consider.’ Venn carefully wiped his hands. ‘I presume the Grieves will inherit his estate.’

‘According to Sarah Grieve, Ley didn’t believe in inherited wealth,’ Jen said. Her mouth was full of pizza. Not a good look. Mel would never speak with her mouth full. ‘She wasn’t very hopeful that their family would get anything. She thought it might all go to charity.’ A pause. ‘You might be interested to know that John Grieve claimed to be in Spennicott yesterday afternoon, boss.’

‘Very interested. A coincidence, do you think?’

‘He wasn’t visiting the old folks’ home. And he claimed he’d never heard of Paul Reed. He’s interested in taking over a farm on the edge of the moor there. He’d hoped Francis might invest in the venture, because he’d bought most of the village already.’

Ross could see Venn considering that. ‘So, if anything, that family might actually lose out by Francis’s dying?’

‘I suppose.’ Jen hesitated and Ross saw there was more to come. ‘John Grieve seemed very tense to me, jumping between anger and depression. Moody. Sarah says he spends a lot of time on the computer.’

‘You think he might belong to the Suicide Club?’

Jen shrugged. ‘It’s certainly worth checking out.’

‘I visited Lauren Miller yesterday,’ Matthew said. ‘It seems probable that her rejection of Ley was the trigger to his suicide.’ A pause. ‘She’d learned a little about the Suicide Club from Nigel. She’s technically competent and had found her way into the chatroom. Apparently, the moderator, the person who seems actively to be advocating suicide, calls themselves the Crow. Lauren couldn’t get beyond the nickname, though.’ He looked up at Ross. ‘Could your friend Steve do that? It’s really urgent that we have that information.’ Again, his voice was disapproving, as if Ross was the person causing the delay.

‘If anyone can, he’ll be the one to do it. I’ll call him as soon as we’re done here.’

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members