AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Four

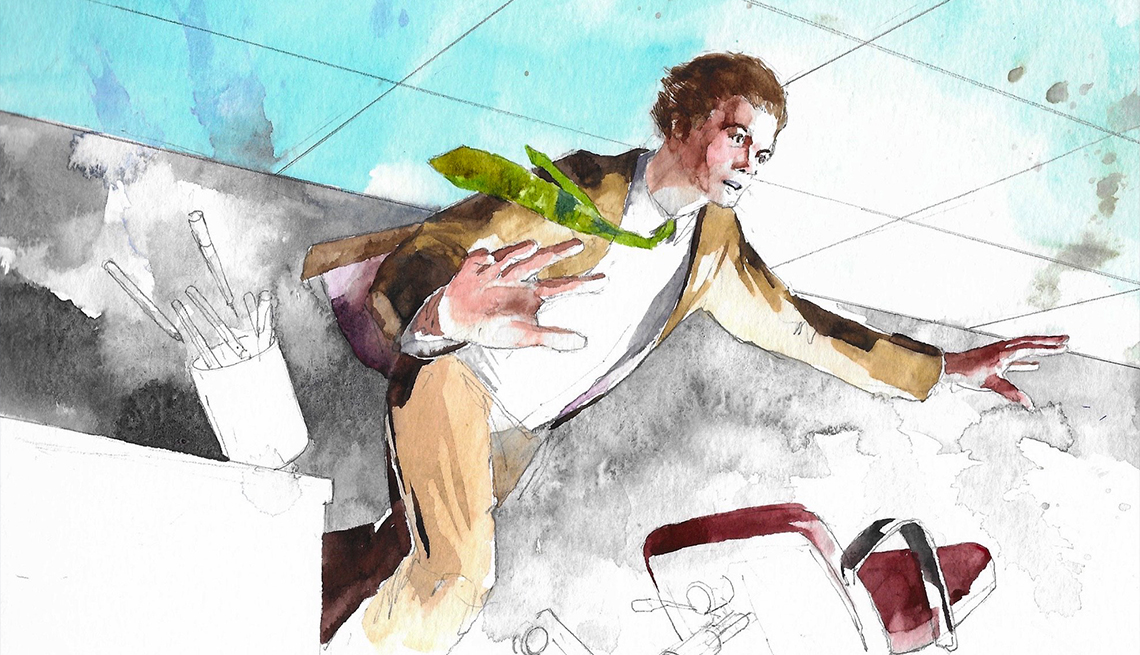

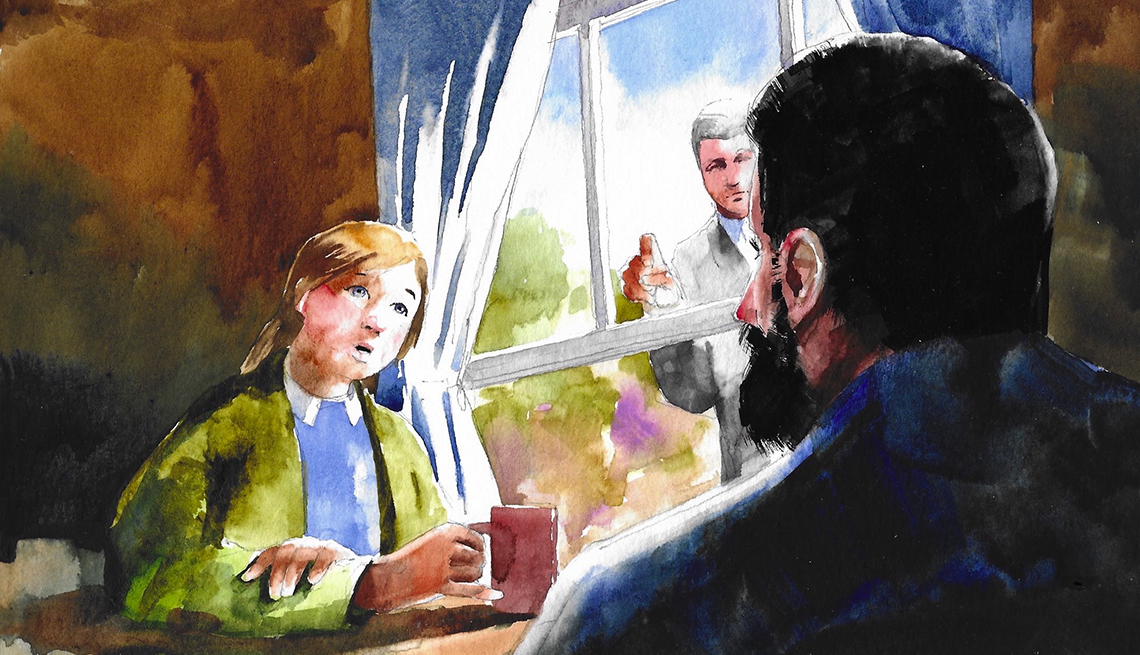

EVE LOOKED ACROSS THE TABLE AT the red-haired detective with the nasal, grating northern voice and wished she’d just f--- off and leave her alone. At this particular point in time she didn’t care who’d killed her father. All that mattered was that he was dead, that she’d be alone, with nobody to hold her when she was miserable, or make her laugh when she needed cheering up. Her anger was undirected, or perhaps more directed towards him, for leaving her, than at the person or persons who’d made it happen. But Eve was polite. She’d been well brought up by her parents. So, she sat at the big table in the shadowy, cool kitchen and she drank tea, and she answered the intruder’s questions.

‘Tell me about the other residents,’ the detective, Jen Rafferty, said. ‘I’ve met Wesley, but I don’t know the others.’

‘John and Sarah Grieve. They’ve got twins. Daisy and Lily. They’re very cute. The girls, I mean, not the parents.’

‘How old are the kids?’

‘Just seven. They had their birthday a couple of weeks ago. We had a party.’ My dad came with balloons, different presents for each of the girls. I made a cake.

‘What role do the parents play here at Westacombe? How do they fit in?’

‘John’s a farmer and Sarah runs the dairy. She also looks after Frank’s house now his mother’s dead, does his laundry, stuff like that. Things are tight for them financially and he pays her well to do it. She never stops working, even though she’s pregnant again.’ Eve paused for a moment. Sometimes Sarah’s energy made her feel incompetent, idle. ‘Even now, she’s making plans. She’d like to open a tea shop alongside the dairy. That would bring more people in and give Wes and me a chance to sell more of our stuff.’ Eve wondered why she was even mentioning that. She’d been excited when Sarah had first thrown out the idea, but now, what importance could it possibly have?

‘Were Sarah and John at the drinks party with Mr Ley yesterday evening?’

‘Yeah, and the kids for a while. Halfway through, Sarah took them away and put them to bed. She came back later and John went to babysit. He’s not exactly sociable, and I think he was glad to escape.’ Eve paused for a moment but decided to continue. Better to give the woman all the information she needed and then she might be left in peace to cry and howl without an audience. Sometimes, she felt like glass, which was pliable and easy to mould when it was hot. She could be amiable and pleasant, until the stress built up, then, like glass, she became cold and hard and she’d crack under the slightest pressure. She didn’t want to crack in front of the detective. ‘Wes was there too, but just for a while. He’d obviously had a better offer but felt the need to show his face. To keep Frank sweet.’

‘Frank is Francis Ley?’

‘Yeah, of course.’ Jesus, what’s wrong with this woman? She’s supposed to be a detective. I’ve already told her that.

‘What time did the party break up?’

‘It wasn’t really a party, just a few drinks. If anything, it was a kind of business meeting.’

‘In what way?’

‘Sarah brought up her idea of opening a tea shop. Obviously, we’d have to get Frank’s approval. There’s spare space by the side of the dairy, which would be ideal, but we couldn’t go ahead without him.’

‘What did he say?’

‘It was a bit disappointing, actually. He said he’d never envisaged this place becoming so commercial. He was worried about access and parking. It’s okay for him, though. He’s minted. He doesn’t need to be commercial.’ The detective was scribbling in a notebook and Eve felt compelled to add, ‘Of course, it’s Frank’s place and we’re lucky to be here. He doesn’t charge anything close to the going rent. It obviously has to be his decision.’ She wouldn’t like to come across as ungrateful. Even now, she realized, with her father stabbed, looking like a slaughtered animal, his body still on the studio floor being mauled by strangers, she was worrying about what people thought of her.

‘So, there was this discussion over drinks?’ Jen Rafferty said. ‘How did it end?’

‘With Frank asking Sarah to draw up proper plans. He said he’d think about it. And we all drifted away about nine. Sarah went back to the cottage.’

‘And you?’ The woman looked up from her notebook. The red fringe almost hid intense brown eyes.

‘I went to the studio for an hour, then I went home too, to my flat in the loft. I was in bed by ten thirty.’

‘You didn’t hear from your father at all during the evening? He didn’t say he planned to come over?’

Eve shook her head. ‘There’s no phone reception in the studio, but there were no missed messages or calls. I checked before I went to bed.’

There was a moment of silence. The detective seemed to be choosing her words carefully. ‘You saw how your father was killed.’

Eve couldn’t speak. The image of bloody glass flashed like faulty neon in her head. It occurred to her that she might never be able to work with the material again. But there had to be a response. She nodded.

‘That piece of glass. Did you recognize it? Was it something you made?’

The picture appeared again, like something from one of the arty films she sometimes dragged her father to see at the Woodyard. All flashbacks and jerky cuts.

‘Yes. I’d been commissioned to make a couple of vases for a smart new shop in Ilfracombe. Tall. Green. Big enough to hold lilies. The shard came from one of those.’ She’d been so proud when they were finished, just the shade of green she’d been looking for. Supremely elegant.

‘I assume it hadn’t been broken when you last saw it?’

‘No, they were both on the shelf in the corner when I left the studio. I’d agreed to deliver them on Monday.’ Again, she pictured the scene. ‘One of them is still there. They were as identical as pieces of hand-crafted glass could be.’

The sun must have shifted, because a beam was shining through the window, lighting dancing motes of dust.

‘I’m sorry.’ And Jen Rafferty did sound genuinely sorry for these questions, for making Eve relive the moment of finding her dad. It seemed she understood the anguish she was causing.

Eve thought that in different circumstances she and Jen Rafferty might even get on. Eve had done her MA in the Glass Centre in Sunderland, and had liked the northerners she’d met there. Something about Jen took her back to that space on the Wear, perhaps the most creative, and happiest, time in her career. But she didn’t want to start crying again and she tried to rekindle her earlier resentment. Anger was easier than overwhelming grief. ‘Have you finished?’ The question was so sharp that it was almost rude.

‘Nearly.’ Jen paused. ‘Can you think of anyone who would have wanted your father dead?’

‘Of course not!’ This was close to laughable. ‘He was kind, gentle, understanding. He’d spent most of his career as a doctor specializing in end-of-life care.’

‘And more recently for an organization which investigated his former colleagues and poked around in their business,’ Jen said. ‘That could have been tricky, if he was investigating them. He hadn’t made enemies through his work?’

‘He never spoke about work.’ That was true, Eve thought, but not quite the full story and perhaps this detective deserved the full story. ‘He found it stressful. More stressful than medicine. I don’t think he found managing a small team of bitchy women easy! When he took it on, he said the job was important. Another way of saving lives. But challenging.’

‘And recently?’ Jen prompted. ‘Had it become more challenging recently?’

‘Something was puzzling him.’

‘Just puzzling? Or worrying?’

That was when Eve realized that this woman wasn’t stupid as she’d first thought, because, of course, Jen was right. Very recently, her father had been worried. He’d tried to hide it but she’d felt the unusual tension, seen the dark rings under his eyes, which suggested he hadn’t been sleeping well. There’d been moments of joy too and she’d wondered about the strange mood swings. Eve nodded. ‘Yes,’ she said, ‘I think something at work was troubling him. He’d become obsessed by it. But he wouldn’t talk about it. He couldn’t.’

‘Confidentiality,’ Jen said easily. ‘Of course. He’ll have kept records, though, and I assume he’ll have discussed it with his colleagues at Patients Together. You can leave all that to us.’

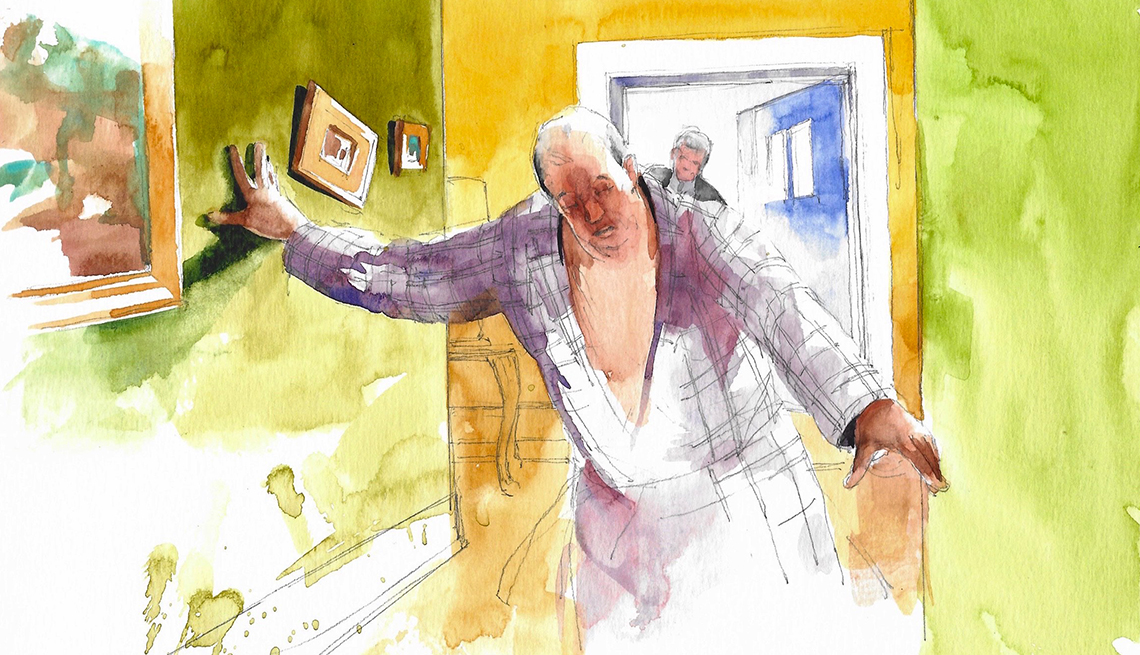

Eve didn’t say anything, but it seemed to her that it might have been the team which had triggered her father’s anxiety. That was guesswork, though. Instinct. And she wasn’t sure how she’d put her feelings into words. In the end she didn’t need to speak, because the kitchen door flew open, letting in a blast of sunshine, and Sarah, earth mother extraordinaire, and possibly her closest friend.

***

After a couple of miscarriages, this time all seemed to be well with Sarah’s pregnancy. She was round and short, and she was wearing a cheesecloth smock over a patchwork skirt of her own design with an expanding elasticated waist. Eve always thought Sarah looked as if she’d stepped straight out of the seventies.

‘Oh Evie,’ she said. ‘I’ve just heard. I mean, I saw the police cars when I came back from taking the girls to gymnastics and all the fuss, but none of them would tell me what was going on. Frank came to the cottage to fill us in. He’d been talking to a policeman.’ She sat beside Eve and put her arms around her. Eve smelled the henna Sarah used to dye her hair and a faint base note of cow.

Eve pulled herself gently away, and thought that Sarah was a bit like a cow herself: placid and wide-eyed. Soon, she would be full of milk. ‘This is Detective Sergeant Rafferty.’ She nodded across the table towards Jen. ‘She’s been asking me some questions.’

‘Oh.’ Sarah turned her attention to Jen, and Eve was aware of her friend’s ritual hostility to the police. She was already bristling. ‘Don’t you think this is a bit soon to be hassling her? She’s only just lost her father.’

Jen didn’t quite roll her eyes. Eve had a moment of amusement and then felt guilty to be enjoying the stand-off between the women.

‘It’s okay,’ Eve said. ‘Really. I want to help find out what happened.’

‘And besides, we’re finished for now.’ The detective smiled at Eve. ‘If you think of anything, though, give me a shout. Anytime. Here’s my card.’ Jen got to her feet, stood for a moment silhouetted in the doorway, the bright light behind her, and then she disappeared.

‘Come into the cottage.’ Sarah could have been bossing around one of the twins. ‘I can get you tea, wine, whatever you need. You can’t be alone at a moment like this.’

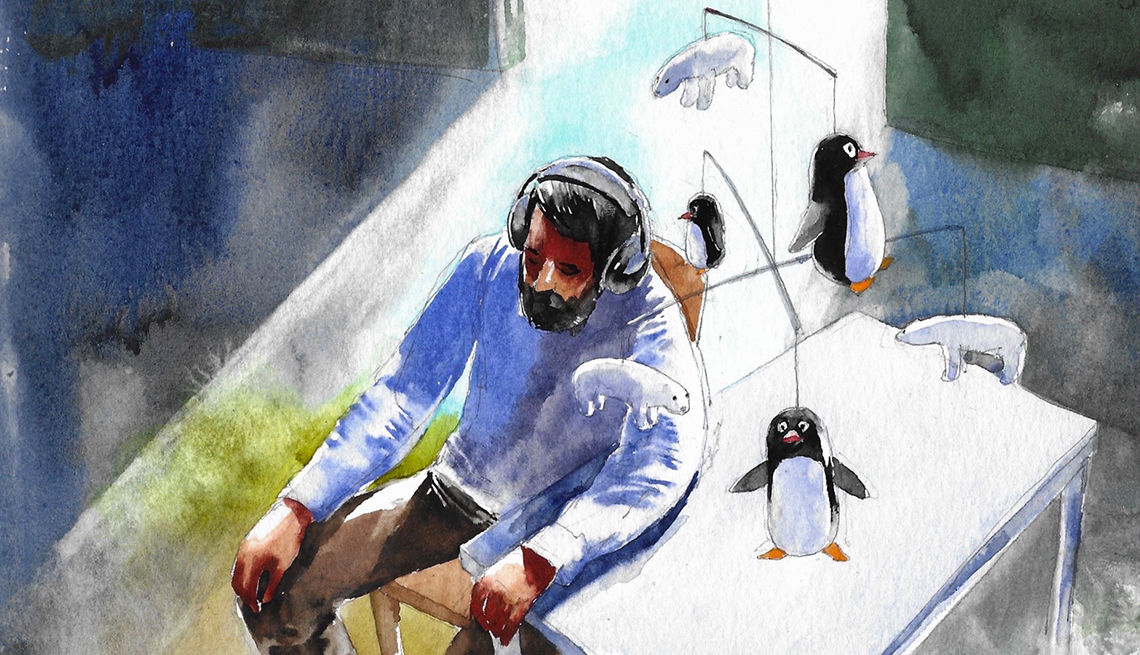

Eve was tempted to go along with the idea. Politeness was a habit. But really, she couldn’t stand the idea of Sarah’s cluttered house, kids’ toys and shoes everywhere, half-finished craft projects, half-eaten plates of food. The dairy was always immaculate but the cottage was her idea of a nightmare.

‘To be alone is absolutely what I need,’ she said, her voice firm. ‘It’s kind of you to offer, but it’s been a shock and I need some time.’

‘Are you sure?’ Sarah hated to be alone, but knew her friend well enough to understand how different they were.

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members