AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Forty

JEN STAYED AT HOME LONG ENOUGH to have breakfast with the kids. Since Nigel Yeo’s murder they’d all been working ridiculous hours and no way would the overtime budget stretch to cover it all. She was due a bit of time off, and it felt as if she’d hardly seen them for days.

Ella was up, showered and dressed without any prompting, but Ben was still in bed when Jen had everything on the table. She knocked at the door of his room and went in. It was a small room, always dark. He never drew the curtains. It smelled of teenage boy, unwashed sheets and stale pizza. On the desk next to the bed, his computer seemed more alive than her son. Something was flashing. He’d probably been on it for most of the night. Some game with his friends. Killing people for fun. Or checking out unsavoury chatrooms? She was tempted to look, but he woke, looked at her, grunted.

‘You’ll be late for school.’ She couldn’t bring herself to be cross. He looked very young, half asleep. ‘Breakfast is on the table.’

When they were both on their way to school, Jen made herself more coffee, then followed Matthew’s suggestion and arranged to meet Lucy Braddick in her new flat in River Bank, a small complex of apartments for learning-disabled adults. She phoned Lucy’s dad, Maurice, to find out when would be a good time to visit.

‘Well, really,’ he said, ‘you should be phoning our Luce. The social workers say that I should be letting her make those sorts of decisions. She should be speaking for herself.’ His voice was slow, his accent as rich and broad as his daughter’s.

‘I don’t have her phone number, though.’ Jen left a pause. ‘I was hoping you might be there, Maurice. She’ll be a bit more confident with you around, and I don’t always understand her speech so well.’

‘She’s not on shift at the Woodyard until this afternoon,’ Maurice replied. ‘I suppose I could phone her and ask her to stay in this morning, warn her that we’ll be calling by.’ Jen could tell that he was delighted to have an excuse to visit his daughter. ‘I was planning to come into Barnstaple to do a bit of shopping anyway.’

While she was waiting until it was time to visit Lucy, Jen pulled together images of the women Wesley Curnow had known. She was reminded of the Simon Walden investigation, another occasion when she’d shown photographs to a woman with Down syndrome, but then Lucy had been a potential victim, not a witness. Jen found pictures of Martha and Janey Mackenzie; they’d appeared in the local newspaper at the time of Mack’s death. Both women were wearing black and looked gaunt. Even Martha was looking away from the camera, not playing up to the crowd. George was there too, and the article used his words, as he’d railed against the system that had let his son down. Cynthia was easy to find. Jen chose an image of her friend wearing a vivid red and pink silk dress. She looked at it for a moment and experienced something akin to grief because the friendship they shared was slipping away. It felt like a kind of bereavement.

Lucy lived in a three-storey block of new flats built on land which had once been owned by the timber factory. The building itself had been transformed into the Woodyard Centre, but the land had been released for development and the independent living apartments were part of the site. They stood next to a small estate of family social housing and looked out over a children’s playground. Jen used the Woodyard car park and walked past the centre to reach Lucy’s place. Just as she was passing the Woodyard entrance, she saw Cynthia approaching from inside. She was carrying a rolled-up yoga mat. It would be impossible to avoid bumping into her.

‘How’s it going?’ Jen thought no f---ing way was Lady Cynth just going to march past with her nose in the air as if they didn’t know each other, as if they hadn’t once been best mates.

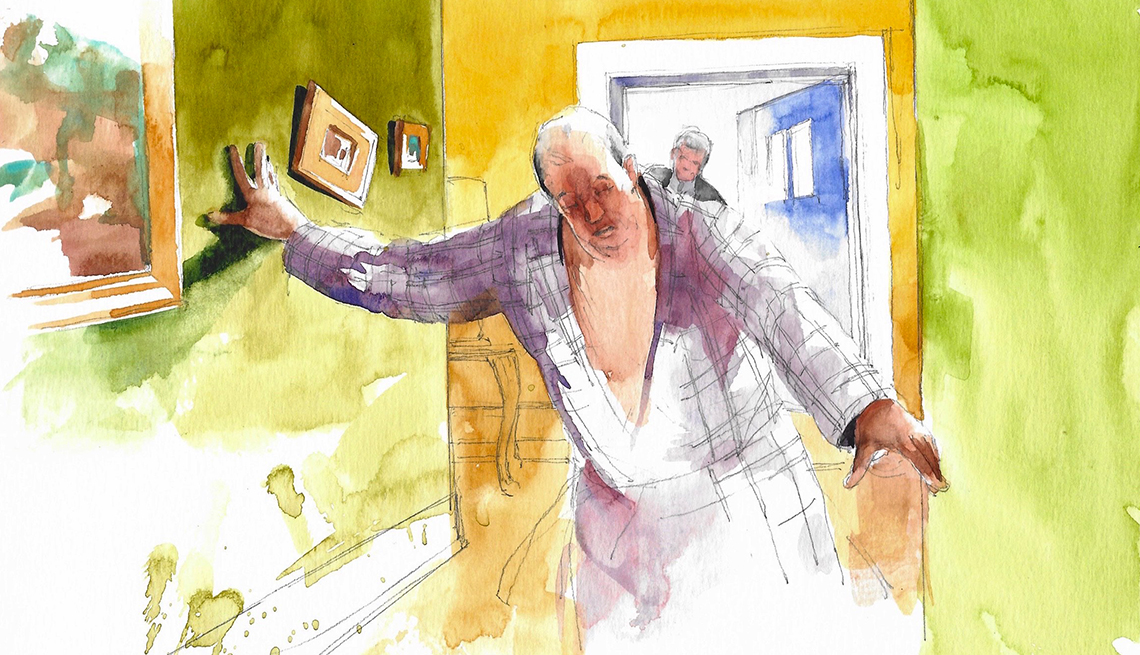

Cynthia stopped and shrugged. ‘Pretty dreadful.’ It sounded like an admission of failure. This wasn’t the old Cynthia of high energy and endless optimism. ‘Roger hardly speaks. He’s working twelve-hour days and when he’s home he locks himself in the office. He seems to be awake most of the night.’ She looked straight at Jen. ‘I’m worried about him. Even when things were really bad in London, he wasn’t this low.’

‘You think he’s depressed? I mean, clinically depressed?’

‘Yeah, I do.’ Cynthia was on the verge of tears. ‘I’ve said he should go to a doctor, but he tells me to leave him alone. There’s this anger. I mean, if he was just sitting in a corner weeping, I could handle it, but there’s a terrible rage. Against the world and me. For some reason he blames me for all that’s happening to him.’ A pause. ‘We were never soulmates, you know. We never lived in each other’s pockets. But in a way, that was why it worked. We were so different that we learned from each other, there was something new to discuss when we did come together. But now? I feel as if I’ve lost him.’

Jen thought this was one of the unconsidered effects of two murders; stress and suspicion were causing individuals, relationships and even communities to fall apart. She looked at her watch. She should be chatting to Lucy. ‘Will you be around all morning? I’ll call in, shall I? You can make me one of your spectacular coffees.’

A moment of silence. Jen thought that if the offer was rejected, the friendship would be over for good. No way back. But Cynthia smiled. ‘Yeah,’ she said. ‘I’d really like that.’

***

Maurice was already in the flat when Jen got there, but it was Lucy who let Jen in, proud as punch. She held her arms wide. ‘Welcome.’

The place gave out the vibe of a student hall of residence, but Lucy had her own living space—a sitting room with a kitchen at one end—as well as the bedroom and a shower room. She insisted on showing Jen round, before putting the kettle on and carefully spooning instant coffee into three mugs.

‘There’s a care worker onsite,’ Maurice said, ‘but Luce manages everything, don’t you, maid?’

‘Yep.’ She beamed.

‘We need your help again,’ Jen said, ‘but there’s no danger this time. Honest.’ The last statement was aimed at Maurice, not Lucy. ‘I just need you to look at a few pictures. Let me know if you saw any of these women on Sunday after Wesley had been in the cafe. If you finished work soon after, you might have noticed someone while you were walking home.’

‘Sure,’ Lucy said.

Jen thought she was proud to be asked and desperate to help. She worried that Lucy would try too hard, would convince herself that she recognized one of the faces just to please. ‘It’s not a test, Luce. It’s just as important you tell me if you don’t see anyone you know. Just as useful.’

Lucy nodded.

But in the end, when Lucy just stared blankly at the pictures, even at someone like Cynthia, who was a regular in the cafe, they all had a sense of disappointment.

‘I just don’t remember seeing anyone,’ she said. ‘When I left work, a bus came in to the stop in front of the Woodyard and people got off. I knew two of my friends from River Bank had gone to Bideford to see their families and I was looking out for them. They’d texted to say they were on their way home. I thought I could walk back to the flat with them. I saw them get off the bus and I waited for them to join me. There was a car coming in and for a minute they couldn’t see me, even though I was waving. The car blocked their view.’ She paused for a moment. ‘That’s a bit weird, isn’t it? Because the centre was closing, so why would anyone come in?’

‘What sort of car, Lucy?’ Jen tried to keep any sense of urgency from her voice.

‘I don’t know anything about cars.’ Now she was starting to sound anxious and upset. Jen could tell that Maurice was about to call a halt to the whole conversation. He fidgeted in his seat and wiped his forehead with a large, white handkerchief.

‘Oh, nor do I.’ Jen jumped in before he could speak. ‘Nothing at all. But you might remember a colour.’

‘Yes!’ Lucy was triumphant. ‘It was black! A big, black car.’

‘I don’t suppose you could tell if it was being driven by a man or a woman?’

Lucy shook her head. ‘I didn’t see. I was looking out for my mates getting off the bus, and then we were chatting.’ Jen left Maurice and Lucy sitting together and drinking more coffee. She was thinking that the father needed the company far more than the daughter did.

***

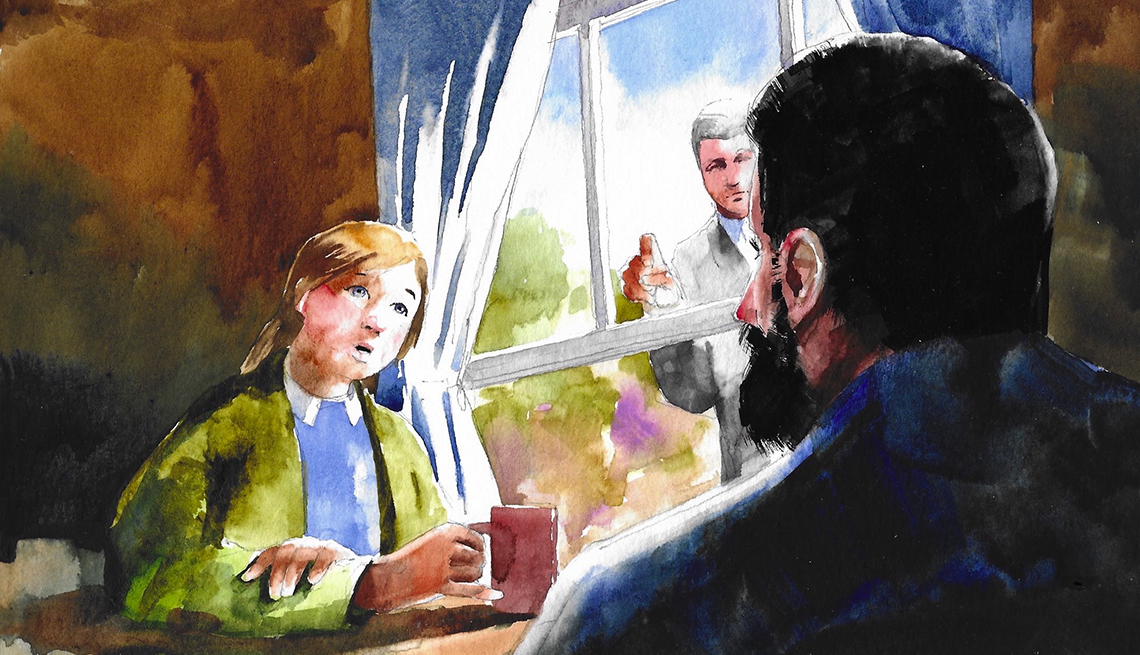

Jen went through the garden gate and round to the back of Cynthia’s house, so she didn’t have to go into the house past Roger’s office. Even if Cynthia wasn’t outside, she’d be in the kitchen, and Jen could knock on the back door. In the end, Cynthia was in the garden, in the chair where they’d had their last conversation. There was a bottle of Pinot Gris in an ice bucket and she’d already poured herself a glass. No chance of a fancy coffee, then. ‘You’re starting a bit early.’ Jen took a seat beside her. She thought this was like being in an entirely different country or continent. The rainforest or some maharaja’s garden in India. She’d never been to either, but despite the drought, there was something exotic about the bright colours and the lush vegetation. ‘It’s lunchtime,’ Cynthia said. ‘It’s civilized to have a small glass with lunch.’ On the table, there was a tray of cheese and cold meat, salad, French bread, a bowl of grapes and strawberries. Two plates, two knives and another glass. ‘You will join me?’

‘Are you joking? Of course! I’m starving!’

Cynthia pushed across a plate and a knife, then poured Jen a glass of wine. She seemed more composed than when she’d bumped into Jen outside the Woodyard, more in control. She’d prepared herself for the encounter.

‘I shouldn’t have the wine. You know the boss. A stickler.’ But Jen took a sip all the same. This was more important than Venn’s rules. ‘What do you think’s going on with Roger?’ She pulled a piece of bread from the loaf and cut a slice of oozing brie, gave all her attention to the taste. Re-establishing a friendship was important, of course. But so was eating when you were given a chance in the middle of an investigation.

‘Well, I don’t think he killed Nigel Yeo and the others.’ Cynthia was prickly again. The tension made her voice shrill.

‘I’m here as a mate,’ Jen said. ‘Not a cop.’

‘You’re always a cop.’

There was no real answer to that and it was Cynthia who spoke next. ‘He’s so stressed. I’m worried about what he might do. I know he would never harm other people. He’s given his life to the NHS, to saving lives. He might not be a medic, but he’s supported them, fought for them. Battled with the government for more resources. More staff. It was that passion that made me fall for him.’

‘Do you think he might be so depressed that he’d consider taking his own life? Is that what you’re saying?’

There was a moment of silence broken by the raucous call of a magpie.

‘Yes,’ Cynthia said. ‘You know, really, I think that he might.’

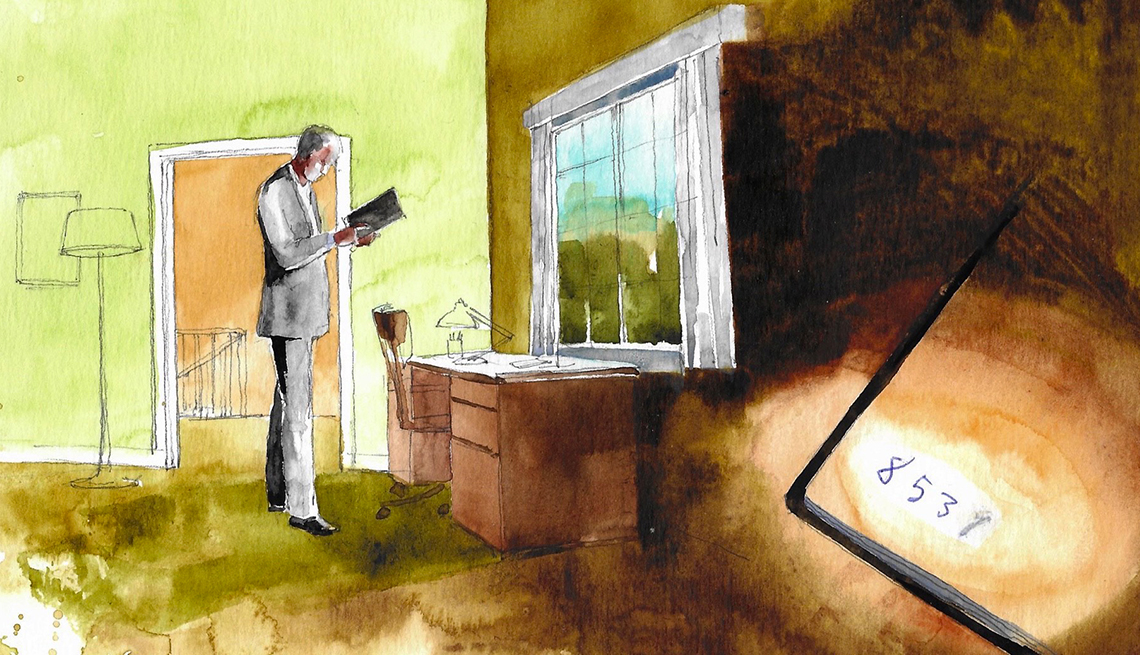

‘Do you know what he’s doing when he’s spending all that time in the house in his office?’

‘What do you mean?’ Cynthia had drunk her wine. She poured herself another glass.

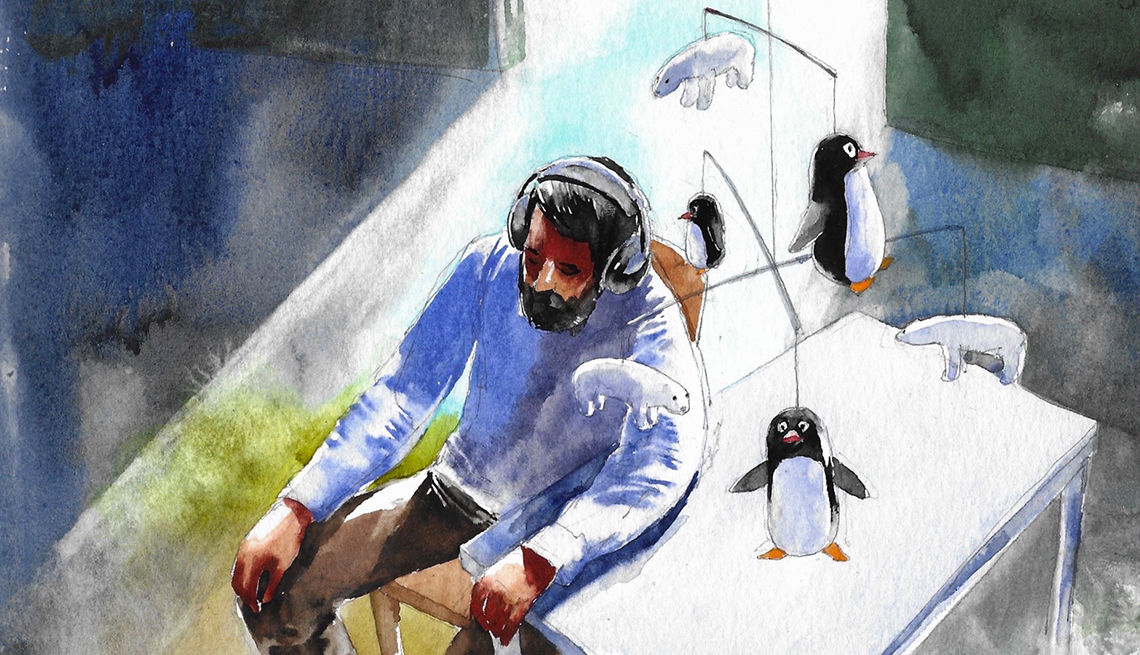

‘We’ve been investigating Mack Mackenzie’s browsing history. He was a member of a chatroom called Peace at Last. It’s a support group for people considering suicide. Within that, there’s a core group who call themselves the Suicide Club. That seems to be made up of more desperate members. We’re worried that one or more of those people are actively encouraging or provoking people to kill themselves.’

‘You think Roger might be a member?’ Now soundless tears were running down Cynthia’s face. ‘That he could be considering suicide?’

‘I’m worried that it might be possible. He was in touch with the professionals treating Luke Wallace, as well as those looking after Mack. We know that both young men were members of the group.’

‘And they both killed themselves.’

‘Yes, they both killed themselves. And Roger might have had access to enough information from the medics treating them to find the site.’ Jen paused. ‘It could have started off as professional interest, a way of proving that something other than healthcare negligence had contributed to the suicides.’

‘I don’t know what to do.’ The tears were still streaming down Cynthia’s face. She’d turned from a confident, competent woman into a child desperate for reassurance, looking for someone to make decisions for her.

‘Do you have the passcode for his computer? We could get in and look.’ And I could find out whether or not he calls himself the Crow.

‘No!’ Cynthia said. ‘The office is his personal space. I never go in when he’s not here.’

Jen was forming an argument in her head. If you’re anxious about his safety, don’t you think that’s more important than intruding on his personal space? But she didn’t have time to speak, because the phone in her pocket buzzed. A text from Matthew Venn, asking her whereabouts and requesting that she come back to the station as soon as possible.

‘I’ve got to go,’ she said. ‘Work. Sorry.’

Cynthia stood up. ‘Of course. It always is work, isn’t it? There’s no escape for you.’ The words sounded like an accusation. She was still crying. It was as if all the liquid in her body was leaking through her eyes, as if she might drown in it.

Jen took the woman into her arms and squeezed her tight. For a moment, Cynthia relaxed enough to allow herself to be hugged.

‘See if you can keep Roger away from the office when he comes in tonight,’ Jen said. ‘If he’s found that website, I can see it could become a kind of obsession. An addiction. It’s probably as compulsive, as exciting, as it gets: watching someone deciding if they’re going to live or die. Then deciding yourself if it’s your turn next.’ Or if you can persuade them to take the final step.

Cynthia nodded, but Jen could tell she wouldn’t stand up to her husband and she wouldn’t ask him about the website or his mood. The couple had got into the habit of leading separate lives and had forgotten how to talk about anything important.

Chapter Forty-One

TECHIE STEVE HAD A FLAT ABOVE a florist’s shop in a lane just off Boutport Street. The smell of the blooms soaking in the buckets outside hit Ross as he waited to be let in. Next door there was a rowdy pub and even this early in the day there were a few people in the beer garden. Ross couldn’t think why Steve was still living here; the noise late into the evening would have driven him crazy, especially in this weather when everyone wanted to be outside. Steve didn’t seem to be bothered by it, perhaps because the flat was long and thin and the rooms got darker and quieter the further in from the street it went. As Ross remembered, it was like moving to the back of a cave.

At the top of the steps that led up from the nondescript door off the pavement, there was a kitchen littered with pizza boxes and foil containers from takeaway restaurants. Empty beer cans. A smell that would set alarm bells ringing with environmental health. This is where Steve was waiting after Ross had pressed the buzzer and climbed into the gloom. The cyber expert was wearing a filthy fleece dressing gown. Nothing else as far as Ross could tell. He stood, blinking.

‘F---, man, what do you want? This feels like the middle of the night.’

‘It’s mid-morning and this is urgent. Where have you got with tracing the Suicide Club members?’

‘Something else came in,’ Steve muttered, still half asleep. ‘Something well paid.’

‘Well, this is a matter of life and death.’ Ross looked at him with something close to disgust. How could someone who was so bright—and so minted—live like this? ‘And you promised you’d stay on it.’

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members