"They brought me down to earth and they lifted me up all in the same moment. ... And even at the young age, I felt that life itself was a mystery."

Q: What other kinds of music did you listen to growing up?

A: Early on, before rock ‘n’ roll, I listened to big band music: Harry James, Russ Columbo, Glenn Miller. Singers like Jo Stafford, Kay Starr, Dick Haymes. Anything that came over the radio and music played by bands in hotels that our parents could dance to. We had a big radio that looked like a jukebox, with a record player on the top.

All the furniture had been left in the house by the previous owners, including a piano. The radio/record player played 78-rpm records. And when we moved to that house, there was a record on there. The record had a red label, and I think it was a Columbia record. It was Bill Monroe singing, or maybe it was the Stanley Brothers. And they were singing “Drifting Too Far From Shore.” I’d never heard anything like that before. Ever. And it moved me away from all the conventional music that I was hearing.

To understand that, you’d have to understand where I came from. I come from way north. We’d listen to radio shows all the time. I think I was the last generation, or pretty close to the last one, that grew up without TV. So we listened to the radio a lot. Most of these shows were theatrical radio dramas. For us, this was like our TV. Everything you heard, you could imagine what it looked it. Even singers that I would hear on the radio, I couldn’t see what they looked like, so I imagined what they looked like. What they were wearing. What their movements were. Gene Vincent? When I first pictured him, he was a tall, lanky blond-haired guy.

Q: Did it make you a better listener?

A: It made me the listener that I am today. It made me listen for little things: the slamming of the door, the jingling of car keys. The wind blowing through trees, the songs of birds, footsteps, a hammer hitting a nail. Just random sounds. Cows mooing. I could string all that together and make that a song. It made me listen to life in a different way. I still listen to some of those old radio shows, and most of them still hold up. I mean, the jokes might be a little outdated, but the situations seem to be about the same. I don’t listen to The Fat Man or Superman or Inner Sanctum in any way you could call nostalgic. They don’t bring back any memories. I just like them.

Q: What did you listen to besides the radio dramas?

A: Up north, at night, you could find these radio stations with no name on the dials, you know, that played pre-rock ’n’ roll things — country blues. We would hear Slim Harpo or Lightnin’ Slim and gospel groups, the Dixie Hummingbirds, the Five Blind Boys of Alabama. I was so far north, I didn’t even know where Alabama was. And then there’d be at a different hours the blues — you could hear Jimmy Reed, Wynonie Harris and Little Walter. Then there was a station out of Chicago. WSM? Is that the one I’m thinking of? Played all hillbilly stuff. Riley Puckett, Uncle Dave Macon, the Delmore Brothers. We also heard the Grand Ole Opry from Nashville every Saturday night. I heard Hank Williams way early, when he was still alive. A lot of those Opry stars, except for Hank, of course, came through the town I lived in and played at the armory building. Webb Pierce, Hank Snow, Carl Smith, Porter Wagoner. I saw all those country stars growing up.

One night I was lying in bed and listening to the radio. I think it was a station out of Shreveport, Louisiana. I wasn’t sure where Louisiana was either. I remember listening to the Staple Singers’ “Uncloudy Day.” And it was the most mysterious thing I’d ever heard. It was like the fog rolling in. I heard it again, maybe the next night, and its mystery had even deepened. What was that? How do you make that? It just went through me like my body was invisible. What is that? A tremolo guitar? What’s a tremolo guitar? I had no idea, I’d never seen one. And what kind of clapping is that? And that singer is pulling things out of my soul that I never knew were there. After hearing “Uncloudy Day” for the second time, I don’t think I could even sleep that night. I knew these Staple Singers were different than any other gospel group. But who were they anyway?

I’d think about them even at my school desk. I managed to get down to the Twin Cities and get my hands on an LP of the Staple Singers, and one of the songs on it was “Uncloudy Day.” And I’m like, “Man!” I looked at the cover and studied it, like people used to do with covers of records. I knew who Mavis was without having to be told. I knew it was she who was singing the lead part. I knew who Pops was. All the information was on the back of the record. Not much, but enough to let me in just a little ways. Mavis looked to be about the same age as me in her picture. Her singing just knocked me out. I listened to the Staple Singers a lot. Certainly more than any other gospel group. I like spiritual songs. They struck me as truthful and serious. They brought me down to earth and they lifted me up all in the same moment. And Mavis was a great singer — deep and mysterious. And even at the young age, I felt that life itself was a mystery.

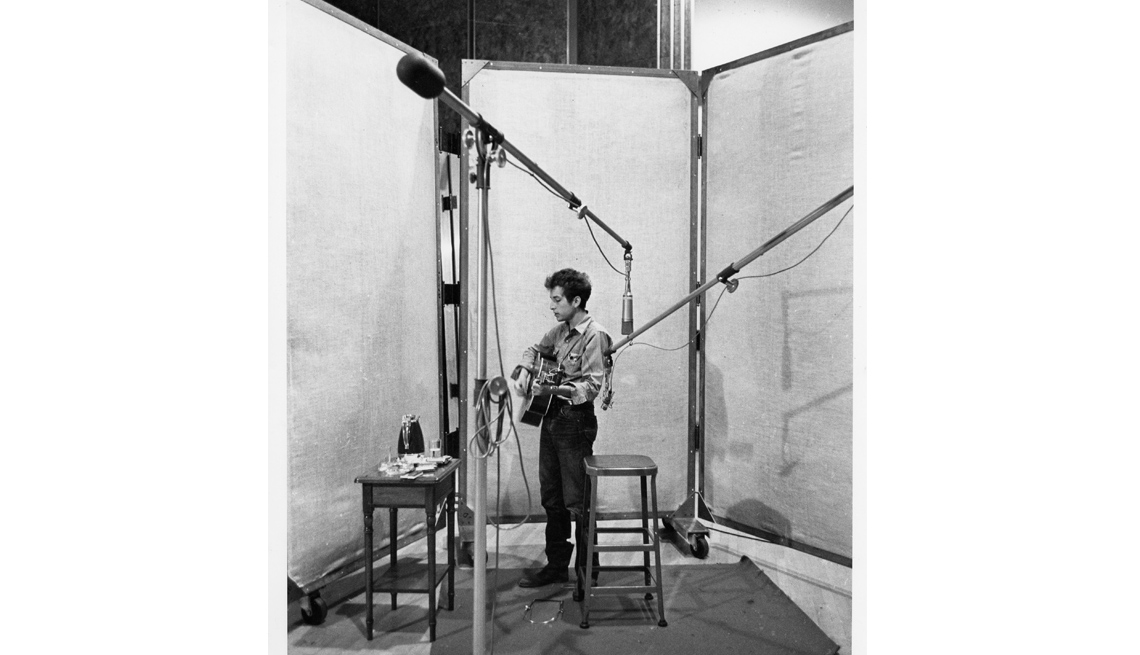

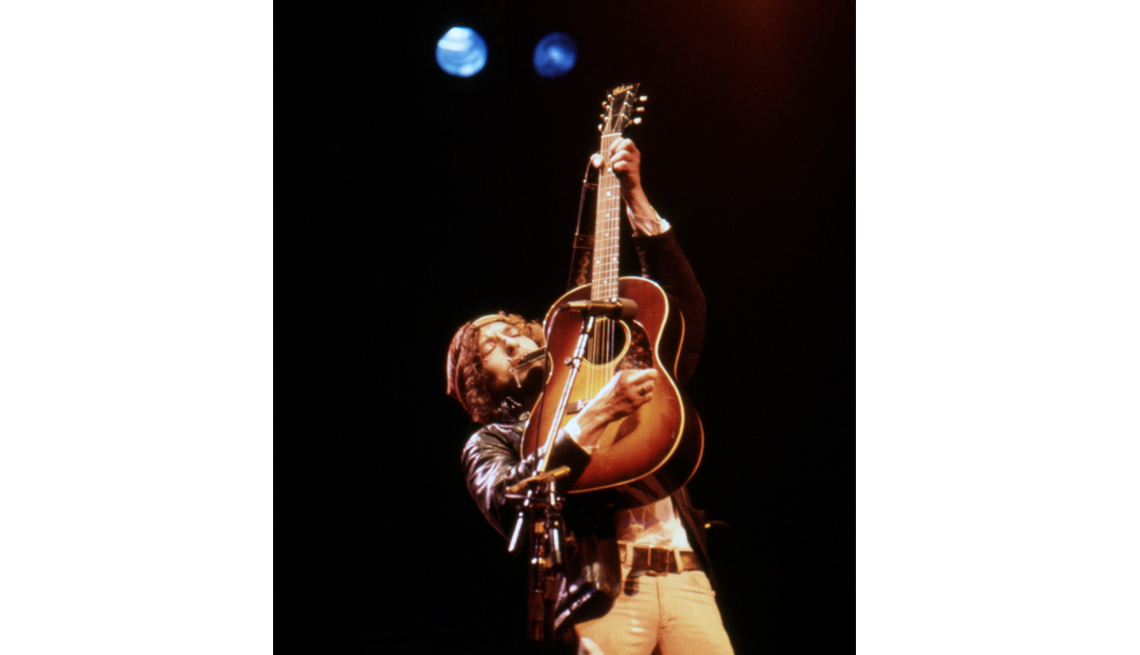

David Gahr/Getty Images

Bob Dylan performs in the Rolling Thunder Revue, May 1976 in Houston, Texas.

This was before folk music had ever entered my life. I was still an aspiring rock ’n’ roller, the descendant, if you will, of the first generation of guys who played rock ’n’ roll — who were thrown down. Buddy Holly, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Carl Perkins, Gene Vincent, Jerry Lee Lewis. They played this type of music that was black and white. Extremely incendiary. Your clothes could catch fire. It was a mixture of black culture and hillbilly culture. When I first heard Chuck Berry, I didn’t consider that he was black. I thought he was a white hillbilly. Little did I know, he was a great poet, too. “Flying across the desert in a TWA, I saw a woman walking ’cross the sand. She been walking 30 miles en route to Bombay to meet a brown-eyed handsome man.” I didn’t think about poetry at that time — those words just flew by. Only later did I realize how hard it is to write those kind of lyrics.

Chuck Berry could have been anything in the music business. He stopped where he was, but he could have been a jazz singer, a ballad singer, a guitar virtuoso. He could have been a lot of things. But there’s a spiritual aspect to him, too. In 50 or 100 years he might even be thought of as a religious icon. There’s only one him, and what he does physically is even hard to do. If you see him in person, you know he goes out of tune a lot. But who wouldn’t? He has to constantly be playing eighth notes on his guitar and sing at the same time, plus play fills and sing. People think that singing and playing is easy. It’s not. It’s easy to strum along with yourself, as you are singing a song and that’s OK, but if you actually want to really play, where it’s important, that’s a hard thing and not too many people are good at it.

Q: And he was always the main guitar player in his band.

A: He was the only guitar player. Yeah. And there was Jerry Lee [Lewis], his counterpart, and people like that. There must have been some elitist power that had to get rid of all these guys, to strike down rock ’n’ roll for what it was and what it represented — not least of all it being a black-and-white thing. Tied together and welded shut. If you separate the pieces, you’re killing it.

Q: Do you mean it’s musical race-mixing, and that’s what made it dangerous?

A: Well, racial prejudice has been around a while, so yeah. And that was extremely threatening for the city fathers, I would think. When they finally recognized what it was, they had to dismantle it, which they did, starting with payola scandals and things like that. The black element was turned into soul music and the white element was turned into English pop. They separated it. I think of rock ’n’ roll as a combination of country blues and swing band music, not Chicago blues, and modern pop. Real rock ’n’ roll hasn’t existed since when? 1961, 1962? Well, it was a part of my DNA, so it never disappeared from me. I just incorporated it into other aspects of what I was doing. I don’t know if this is answering the question. [Laughs.] I can’t remember what the question was.

Q: We were talking about your influences and your crush on Mavis Staples.

A: Oh, the Staple Singers! Mavis! So I had seen this picture of the Staple Singers. And I said to myself, “You know, one day you’ll be standing there with your arm around that girl.” I remember thinking that. Ten years later, there I was — with my arm around her. But it felt so natural. Felt like I’d been there before, many times. Well I was, in my mind.

Q: Did you recall your original thought?

A: No! I was moving too fast. Not until 10 years more beyond that did I remember anything about it.

Q: I was thinking how important it was to you when you were young to chase down those Woody Guthrie records. And I was thinking about how Mick [Jagger] and Keith [Richards] ran all over London to get blues records, and how Neil Young pumped quarters into the jukebox to hear Ian and Sylvia. And now the Internet has all of it — you can just touch a button and hear almost anything in the history of recorded music. Has it made music better? Or worse? More valued or less valued?

A: Well, if you’re just a member of the general public, and you have all this music available to you, what do you listen to? How many of these things are you going to listen to at the same time? Your head is just going to get jammed — it’s all going to become a blur, I would think. Back in the day, if you wanted to hear Memphis Minnie, you had to seek a compilation record, which would have a Memphis Minnie song on it. And if you heard Memphis Minnie back then, you would just accidentally discover her on a record that also had Son House and Skip James and the Memphis Jug Band. And then maybe you’d seek Memphis Minnie in some other places — a song here, a song there. You’d try to find out who she was. Is she still alive? Does she play? Can she teach me anything? Can I hang out with her? Can I do anything for her? Does she need anything? But now, if you want to hear Memphis Minnie, you can go hear a thousand songs. Likewise, all the rest of those performers, like Blind Lemon [Jefferson]. In the old days, maybe you’d hear “Matchbox” and “Prison Cell Blues.” That would be all you would hear, so those songs would be prominent in your mind. But when you hear an onslaught of 100 more songs of Blind Lemon, then it’s like, “Oh man! This is overkill!” It’s so easy you might appreciate it a lot less.

More on Bob Dylan

Find out what Dylan has to say about Shakespeare, Picasso and other inspiring artists in The Man of Strong Opinions

What year did the Bard legally change his name from Robert Zimmerman to Bob Dylan? Get the answer to this and more Dylan trivia questions in our Ultimate Fan Quiz

Music critic Bill Flanagan gives us a crash course on Dylan. From his years at the Newport Folk Festival to his Medal of Honor from President Obama, it's all here in our Bob Dylan Primer