AARP Hearing Center

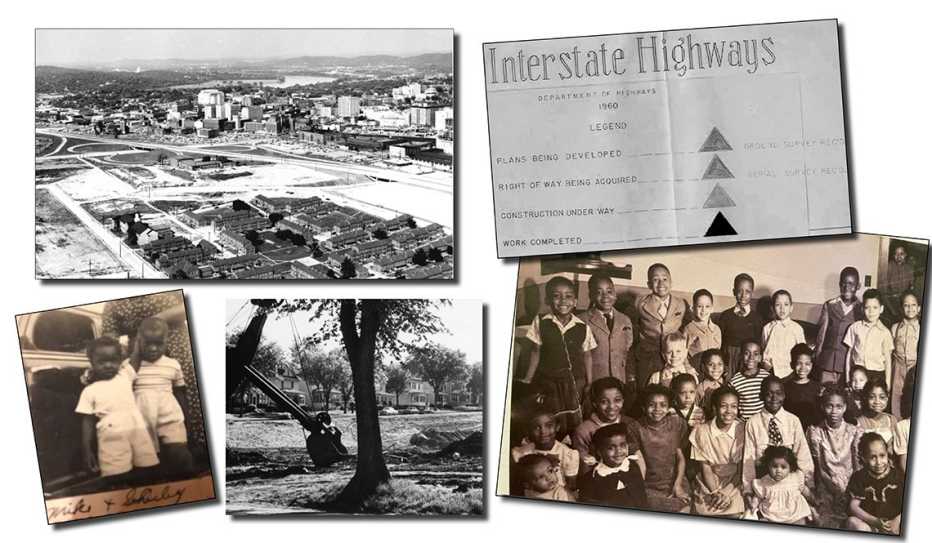

As a home to Black families and individuals migrating from downtown Saint Paul, Minnesota, and other areas, the city’s Rondo neighborhood thrived during the first half of the 20th century. An exemplar of Black social entrepreneurship, academic excellence and a vibrant arts culture, the community was centered on Rondo Avenue itself, flanked by University Avenue to the north and Selby Avenue to the south. Rondo was a critical haven for Black residents in Minnesota’s Twin Cities during the peak years of de facto segregation and the Civil Rights Movement.

An Alternate Route

"Initial expressway plan for the Minneapolis-St. Paul connection was known as the St. Anthony Route, which would follow St. Anthony Avenue (parallel to University Avenue) and extend right through the heart of the Rondo neighborhood. St. Paul city engineer George Harrold opposed this plan — citing concerns about loss of land for local use and the dislocation of people and business — suggesting the alternative Northern Route, which would run adjacent to railroad tracks north of St. Anthony Avenue, leaving the street intact. Ultimately, the St. Anthony Route was chosen and approved by government officials citing its efficiency."

— Minnesota Historical Society Library

Passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act in 1956 led to the construction of Interstate 94. Eminent domain forced more than 1,000 families and more than 100 Black-owned businesses to relocate, often with great financial loss.

The state had the option of building the freeway parallel to an abandoned railroad line (see box), but chose to build through the Rondo neighborhood, splitting the community in half. In the ensuing decades, a once-flourishing community deteriorated due to isolation (separated from the city by an uncrossable highway), underinvestment and a decrease in population.

Marvin Roger Anderson — a retired lawyer and, for more than two decades, Minnesota's State Law Librarian — witnessed the near eradication of the Rondo community.

In 1983, he co-founded the Rondo Days Festival. More than 35 years later, he was an important figure in the development of the Rondo Commemorative Plaza. In 2016, AARP Minnesota honored him as a "community builder" by including him in its first-ever "Minnesota 50 Over 50" list.

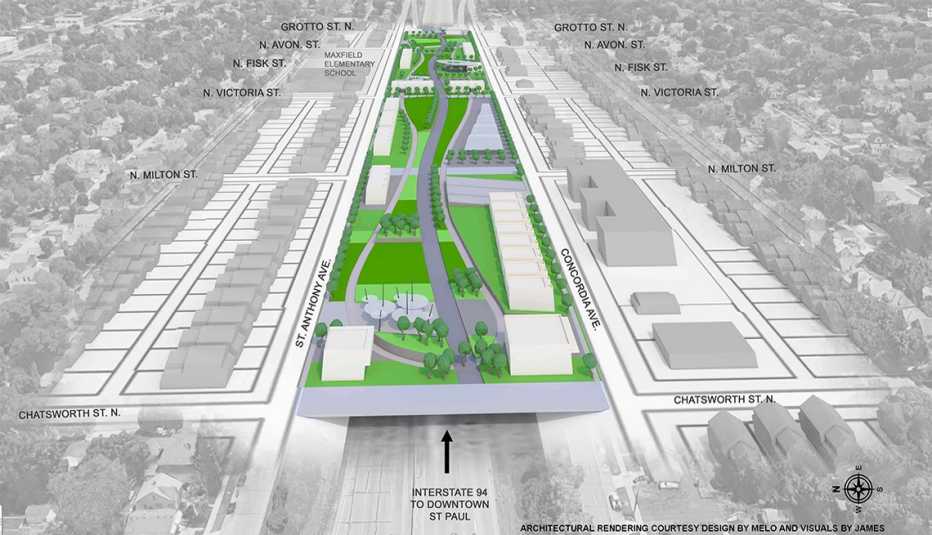

At age 82, Anderson continues to stand at the forefront of efforts to restore Rondo’s glory and celebrate what was lost. He serves as the board chair of the commemorative plaza, the Rondo Center of Diverse Expression and ReConnect Rondo, a nonprofit that is advocating for the creation of a 22-acre, 3,000-linear-foot land bridge (pictured below) traversing I-94.

AARP: Tell us about living in Rondo.

Marvin Anderson: I knew from an early age that my Rondo community was a special place. The parts of me that formed the core of my being, that have endured and guided my paths, came from Rondo. I am very thankful that I was born and matured at a time when the Rondo of which we speak today as memory was a living, breathing, cauldron of energy and vitality — and a sometimes messy bastion of love, pain, sorrow and laughter. Just saying the word Rondo opens a floodgate of memories of family, first loves and friends I will never forget.

Rondo as a community was about 40 years old when I arrived on the scene in 1940. The Great Depression was over, and Rondo was about 10 years into a productive period. By then, the vast majority of the Negro population of Saint Paul lived in Rondo. It was a thriving center of activity. Rondo was the heartbeat, the absolute center of collective attention.

The residents of Rondo were well-organized, diverse and dynamic. More than any other group, they shaped the spirit of the community and willingly shared their joy with Rondo’s Jewish and white residents. Doctors, lawyers, architects walked the streets and shared the village with barbers, beauticians, social workers, Pullman porters, waiters, cooks, maids, players, hustlers, musicians, public servants and store clerks who lived as their neighbors on the same streets.

There were schools, churches, sports, social clubs, restaurants, buildings and homes reflecting the range of individuals and families living there. Community centers such as Hallie Q. Brown and Ober Boys were gathering places offering a variety of events and activities for the young and old. One could pay a visit to any of the Black-owned barber and beautician shops or bars and hear local, national and international ideas being discussed along with conversations about the next dances and balls. There was a Black press that provided another point of view from the white newspapers.

As kids growing up, we were given the opportunities to play sports, join Scouts, walk to movies, hang on the corner, ice fish, ice skate, ride bikes, go to parties, learn to drive and dance the night away.

When I talk to friends from the past who no longer live in Rondo, I am always pleased when they confirm that they also remember the absolute joy we had absorbing the contours, shapes and interests of our unique community and way of life. We listened to the stories being told, we watched older kids, our parents and others perform the rituals that cemented the bonds of Rondo.

Undoubtedly, there will be those who disagree with my recollections and descriptions. If someone says I have a selective memory of Rondo, remembering only the “good stuff,” I wouldn’t disagree.

Certainly not all was upbeat. Like any predominately Black community, residents were subjected to inequalities, debasements, disrespect, low wages, poor working conditions and a host of other urban ills.

Many families suffered the ills confronting Rondo before the freeway construction began in the 1950s. I believe they would have eventually made progress reducing those challenges, had the decision not been made to route the freeway through Rondo Avenue and destroy any chance for an acceptable improvement of our economic and social conditions.

The freeway had an overwhelming physical, cultural and emotional impact on life in Rondo. Looking back on what occurred, it would be hard not to conclude that the effect of losing homes, businesses and jobs exacerbated the preexisting woes and ushered in a devastation and trauma that many still experience many decades later.

Remembering Rondo

"80% of Saint Paul’s African American population once lived in Rondo. They enjoyed friendship, culture and pride in this mixed-income community with a flourishing middle class. Rondo was a bustling place where businesses prospered. A lively neighborhood where residents danced their steps, played their games and swayed to a rhythm all their own. People worshiped together. They fell in love. They raised families. They believed in the promise of a better tomorrow for their children.... Rondo was devastated when I-94 ripped through the community.... The effects of the fateful decisions made decades ago are still being felt today."

I include my family among those that suffered great lost.

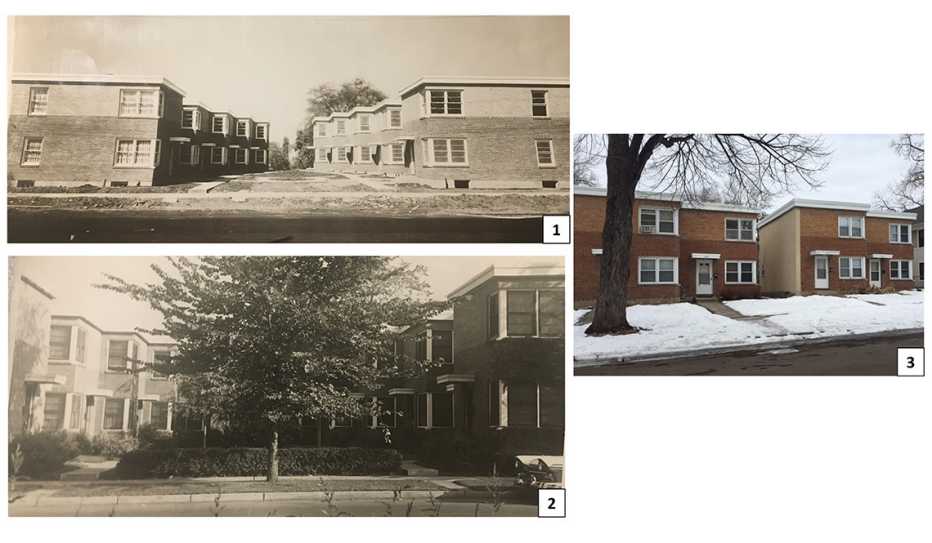

My father and four of his friends built the largest housing project in Rondo. It consisted of 12 two-story townhomes constructed in 1947 and called Rangh Court. The group applied for and received the largest Federal Housing Authority mortgage backed loan ever given to nonwhite applicants in the state of Minnesota. The loan was for $247,000. In 2022 dollars that's equivalent to more than $3 million.

My family was the resident manager, meaning we were responsible for renting, maintaining, repairing and beautifying the units and compound. It was a successful project and over the course of it existing the court never had a vacancy. Eventually, ownership was transferred to my father and my godfather, and both of them drilled into me that my responsibility was to go away to college, study and then return as a junior partner for similar projects in Saint Paul and for the Black communities in Minneapolis.

"The freeway had an overwhelming physical, cultural and emotional impact on life in Rondo. Looking back on what occurred, it would be hard not to conclude that the effect of losing homes, businesses and jobs exacerbated the preexisting woes and ushered in a devastation and trauma that many still experience many decades later."

— Marvin Roger Anderson