AARP Hearing Center

How can ADUs be added to existing neighborhoods?

Recognizing that ADUs may represent a new housing type for existing neighborhoods, communities often write special rules to ensure they’ll fit in well. These guidelines typically address visual compatibility with the primary dwelling, appearance from the street (if the ADU can be seen) and privacy for neighbors. Rules that help achieve these goals include:

- height and size caps mandating that ADUs be shorter and smaller than the primary dwelling

- requirements that detached ADUs be behind the main house or a minimum distance from the street

- mandates that the design and location of detached ADUs be managed the same way as other detached structures (e.g., garages) on the lot

- design standards for larger or two-story ADUs so they architecturally match the primary dwelling or reflect and complement neighborhood aesthetics

- encouragement for the creation of internal ADUs, which are often unnoticed when looking at the house

Each community can strike its own unique balance between strict rules to ensure that ADUs have a minimal impact on neighborhoods and more flexible rules that make them easier to build.

What about parking?

ADU regulations often include off-street-parking minimums on top of what’s already required for the primary dwelling. Such rules can prevent homeowners from building ADUs if there’s insufficient physical space to accommodate the parking. However, additional parking often isn’t needed.

Data from Portland, Oregon, shows that there are an average of 0.93 cars for each ADU, and that about half of all such cars are parked on the street. With fewer than 2 percent of Portland homes having ADUs (the highest percentage in the country), there is about one extra car parked on the street every six city blocks. This suggests that any impacts on street parking from ADUs are likely to be quite small and dispersed, even in booming ADU cities. More-realistic parking rules might:

- require new parking only if the ADU displaces the primary dwelling’s existing parking

- waive off-street-parking requirements at locations within walking distance of transit

- allow parking requirements for the house and ADU to be met with a combination of off-street parking, curb parking, and tandem (one car in front of the other) driveway parking

What can be done about unpermitted ADUs?

It’s not uncommon for homeowners to convert a portion of their residence into an ADU in violation (knowingly or not) of zoning laws or without permits.

Such illegal ADUs are common in cities with tight housing markets and a history of ADU bans. One example is New York City, which gained 114,000 apartments between 1990 and 2000 that aren’t reflected in certificates of occupancy or by safety inspections.

Some cities have found that legalizing ADUs, simplifying ADU regulations and/or waiving fees can be effective at getting the owners of illegal ADUs to “go legit” — and address safety problems in the process.

How can certain uses be allowed and others restricted?

Communities get to decide whether to let ADUs be used just like any other housing type or to create special rules for them. Some municipalities take a simple approach, regulating ADUs just as they do other homes. So if a home-based childcare service is allowed to operate in the primary dwelling, it is also allowed in an ADU. Conversely, communities sometimes adopt ADU-specific regulations in order to avoid undesirable impacts on neighbors. Examples include:

- Limiting short-term rentals: ADUs tend to work well as short term rentals. They’re small and the owner usually lives on-site, making it convenient to serve as host. However, if ADUs primarily serve as short-term rentals, such as for Airbnb and similar services, it undermines the objective of adding small homes to the local housing supply and creating housing that’s affordable.

In popular markets, short-term rentals can be more profitable than long-term ones, allowing homeowners to recoup their ADU expenses more quickly. In addition, short-term rentals can provide owners with enough income that they can afford to occasionally use the ADU for friends and family.

A survey of ADU owners in three Pacific Northwest cities with mature ADU and short-term rental markets found that 60 percent of ADUs are used for long-term housing as compared with 12 percent for short-term rentals.

Respondents shared that they “greatly value the ability to use an ADU flexibly.” For instance, an ADU can be rented nightly to tourists, then someday rented to a long-term tenant, then used to house an aging parent. ADUs intended primarily for visting family are sometimes used as short-term rentals between visits.

Cities concerned about short-term rentals often regulate them across all housing types. If there are already rules like this, special ones might not be needed for ADUs. An approach employed in Portland, Oregon, is to treat ADUs the same except that any financial incentives (such as fee waivers) to create them are available only if the property owner agrees not to use the ADU as a short-term rental for at least 10 years.

- Requiring owner-occupancy: Some jurisdictions require the property owner to live on-site, either in the primary house or its ADU. This is a common way of addressing concerns that absentee landlords and their tenants will allow homes and ADUs to fall into disrepair and negatively impact the neighborhood.

Owner-occupancy rules are usually implemented through a deed restriction and/or by filing an annual statement confirming residency. Some cities go further, saying ADUs can be occupied only by family members, child- or adult-care providers, or other employees in service of the family.

Owner-occupancy requirements make the financing of ADUs more difficult, just as they would if applied to single-family homes. But as ADUs have become more common, owner-occupancy restrictions have become less so, which is good. Such requirements limit the appraised value of properties with ADUs and reduce options for lenders should they need to foreclose.

Enforcing owner-occupancy laws can be tricky, and the rules have been challenged in courts, sometimes successfully. However, according to a study by the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, more than two-thirds of properties with ADUs are owner-occupied even without an owner-occupancy mandate.

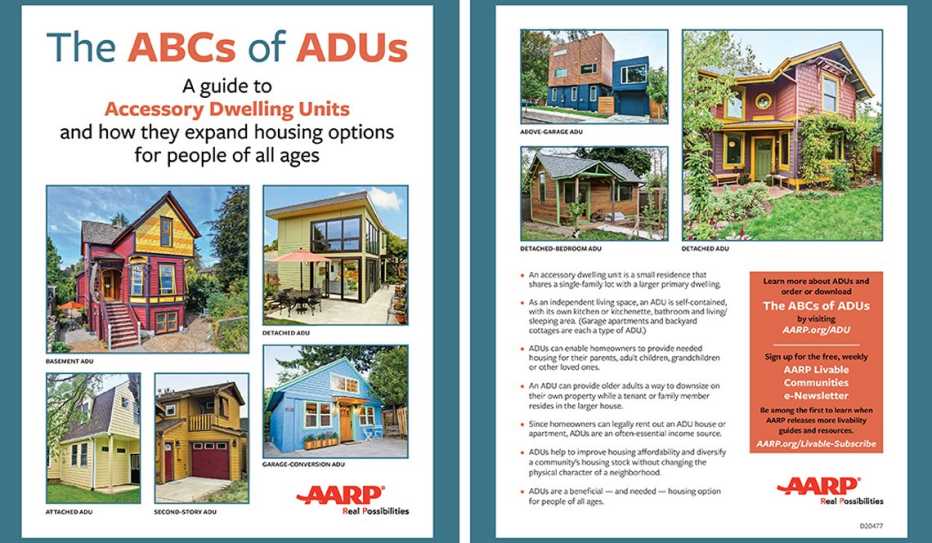

This article is adapted from The ABCs of ADUs, a publication by AARP Livable Communities. Learn more below.

MORE ABOUT ACCESSORY DWELLING UNITS

Visit AARP.org/ADU for links to more articles and to order AARP's free publications about accessory dwelling units.