AARP Hearing Center

John Danicic and Kim Ode are living the suburban American Dream. They built a home on a half-acre lot studded with trees in Edina, Minnesota, where their children attended the highly ranked local public schools. Their driveway easily accommodates their three vehicles, which is handy because Danicic's woodworking projects often overtake the two-car garage.

Yet one of the things they like most about their house is something typically associated with city living — the wealth of shops and services within walking distance.

"We have it all!" jokes Ode. "But really, there is more of a sense of community when you can walk places. That's one of the major reasons we moved here."

"That's my barber," Danicic points out while strolling to lunch at a local diner. "And there's Hello Pizza, where we like to go on Friday nights and sit outside when the weather's nice. And here's the coffee shop, which is a great place to meet up with friends."

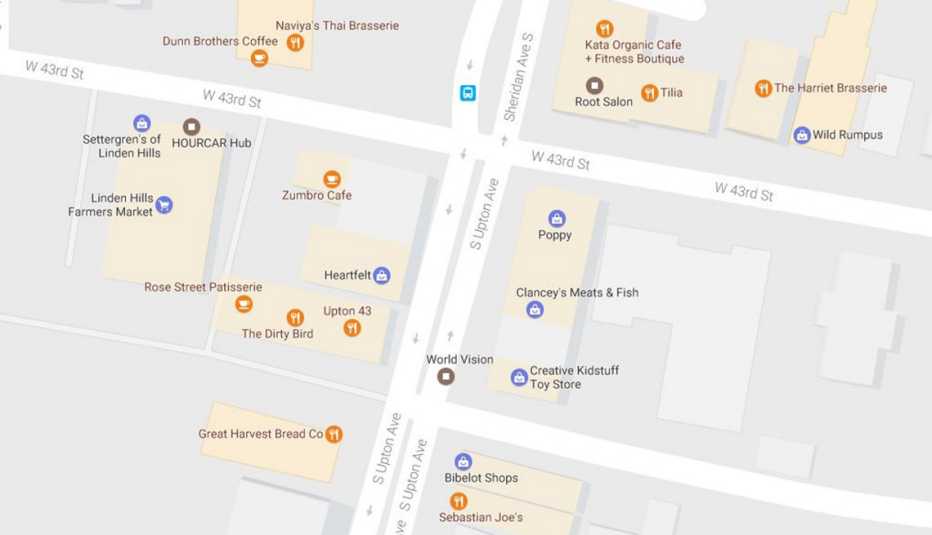

Across the street sits a natural food grocery store, which the pair visits several times a week, and a liquor store, sandwich shop, veterinary office and Chinese restaurant. A few blocks down 44th Street is the Turtle Bakery, with long tables for conversing over pastry and coffee. Walking 10 minutes further, they're in Linden Hills — a neighborhood business district that's home to a hardware store, public library, meat market, toy store, gift shops, their favorite restaurant Upton 43 (named best in town by the Minneapolis Star Tribune) and the Wild Rumpus bookstore (named as one of the best in the country by novelist Ann Patchett in the New York Times).

Welcome to the 20 Minute Village

The phrase "The 20-Minute Village" was made popular by the Portland-based Gerding Edlen development firm, which describes it this way: "Imagine being able to do all of the necessary and enjoyable things that make life great within 20 minutes of your home … Less time spent in transit means more time for family and friends, leisure activities and other meaningful experiences."

"Twenty minutes on foot is ideal," explains Gerding Edlen on its website, "but 20 minutes by transit, bike or even auto is a reasonable goal."

Although we tend to think of walking to work, shopping, cafés and parks as big city amenities, traveling by foot was the foundation of community life in small towns, suburbs and villages before the dominance of cars, parking lots and malls.

The growing popularity of the 20-Minute Village (also known as the urban village) is confirmed by the National Association of Realtors (NAR), whose most recent community preference research found that 85 percent of survey participants said that "sidewalks are a positive factor when purchasing a home, and 79 percent place importance on being within easy walking distance of places."

Walkable neighborhoods are also seeing significant jumps in property values. A one-point increase on Walkscore, a website that rates the walkability of U.S. neighborhoods on a 1 to 100 scale, translates into $3,250 more in value, according to the influential real estate database Redfin.

The Value of Walkability

Walkable neighborhoods are also seeing significant jumps in property values. A one-point increase on Walkscore, a website that rates the walkability of U.S. neighborhoods on a 1 to 100 scale, translates into $3,250 more in value, according to the influential real estate database Redfin.

"This is why downtowns are gaining popularity for the first time since the 1940s," says Robert Steuteville, who closely tracks urban development in the journal Public Square. "Things are accelerating in downtowns and adjacent neighborhoods in places like Portland, Atlanta, Denver, L.A., Washington D.C., Boston, Seattle, Minneapolis-St. Paul and Richmond, Virginia."

But it's also apparent in smaller communities too — like Ithaca, New York, where Steuteville and his family live in a quiet neighborhood that's a 10-minute walk from downtown.

"It enhances our lives in so many ways," he says. "My daughter doesn't have to take a bus to school and can walk to see her friends and take violin lessons. There's a pharmacy around the corner, and you can walk or ride your bike to everything else you need. I know a lot of families here with just one car, even in a household of four or five people," he adds. (According to AAA, the annual cost of maintaining a car in 2016 was about $8,500.)

In addition to existing communities blessed with storefront businesses, a growing number of developments built from scratch qualify as 20-Minute Villages. Belmar — a wholly new community rising from the ruins of the Villa Italia Mall in suburban Lakewood, Colorado — features a town center complete with stores and eateries of every description as well as an Irish pub, bowling alley, ice skating rink and flourishing street life, all conveniently surrounded by townhomes and apartments.

It's All Nearby

While the shift to walkable communities is most pronounced among the millennial generation — who favor walking over driving by 12 percent in the Realtors' survey — many people in their 50s, 60s and 70s are choosing neighborhoods where day-to-day life is not solely dependent on cars.

Across the Mississippi River from downtown Minneapolis stands the new loft building where Lynette Lamb (pictured above) and Robert Gerloff moved with their teenaged daughters two years ago.

"We wanted to be close to things," Lamb explains. "My husband walks to the grocery store every day. It's like we live in Europe. Our daughter walks to her high school. We have a movie theater right down the street, a pharmacy, dry cleaners, our bank, dentist, good transit connections, art galleries, lots of restaurants, and parkland all along the river to walk our dog. And downtown is right across the pedestrian bridge. Even when it's 20 below I'm able to walk down the street to hear a new band I'd heard about." Another advantage of the family's new location, Lamb notes, is that they were able to get rid of one of their cars.

Many senior communities catering to older residents now emphasize walkable amenities. Parkshore Center — an independent- and assisted-living facility in suburban St. Louis Park, Minnesota, where John Danicic's parents lived into their 90s — is just steps from a Target store, full-scale grocery, city park and community recreation center.

The Boston-based firm National Development specializes in building communities where people in their late 70s and 80s can "enjoy a quality of life that's less dependent on a vehicle," says Vice President Michael Glynn. "Our residents love having coffee shops and restaurants they can walk to, see people and enjoy a sociable life." Their latest project, Waterstone at the Circle in the Cleveland Circle neighborhood of Boston, is built close to restaurants, shops and the Green Line light rail, which whisks residents to destinations throughout the area.

We Used to Walk

Vast swaths of America are inhospitable to people who sometimes want to get around by foot, bike, bus or train. That's why Steuteville advocates reviving "Missing Middle" housing, a concept coined by architect Daniel Parolek to describe neighborhoods that are neither high-rise districts nor mazes of suburban cul-de-sacs.

There was a long tradition in this country of mid-size density — single-family houses close together, duplexes and triplexes, and small courtyard apartment buildings that foster lively neighborhood business districts and high transit ridership, all of which are central to the growing popularity of 20-Minute Villages. The problem, says Steuteville, is that "current zoning regulations make it almost illegal to build these kinds of places today."

Luckily, that's changing now in some places, says Robert Ping, director of the WALC Institute. Portland, Oregon, for instance, is planning for 90 percent of its neighborhoods to be 20-Minute Villages by 2030. Stronger social connections are part of the reason, but so is reducing greenhouse gas emissions and boosting public health.

In 2015, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy issued a Call to Action to Promote Walking and Walkable Communities, declaring that "brisk walking can significantly reduce the risk of heart disease and diabetes."

A 20-minute walk is generally about a mile, Ping explains. "But that's a long ways to go to get a quart of milk." He advocates a mix of 5-minute hamlets — offering a corner store, park and café or community meeting place — within larger 20-minute villages that can provide for most of our weekly wants and needs. "Of course in some places, a 20-minute walk can feel like five minutes," he says, noting that the goal is to make it easy, safe and pleasurable to get around on foot.

In a December 2016 Washington Post article about the health hazards of unwalkable suburbia, Gwen Wright, the planning director of Maryland's Montgomery County, said her county aspires to "10-minute living" that enables people to get to their jobs, schools and more within an "inviting" 10-minute walk.

Whether the destinations are 5, 10 or 20 minutes away, the quality of the walk is key. "Walking is a more comfortable experience when you're not passing vast parking lots or blank walls with no windows," observes Ping. "That makes us feel exposed. What we want to see are trees, flowers, interesting buildings at a human scale — and, of course, good lighting at night."

Jay Walljasper — author of the Great Neighborhood Book and the urban-writer-in-residence at Augsburg College — writes, consults and speaks on how to create stronger communities.

Article published February 2017